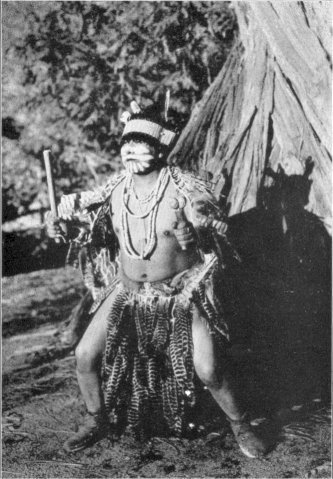

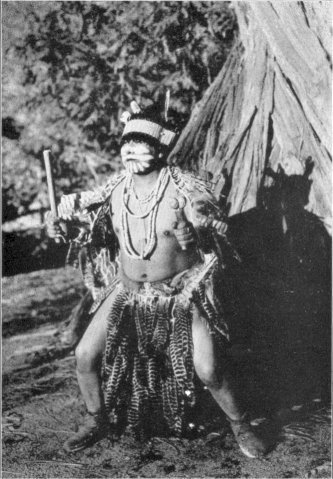

Lee-mee (Chris Brown) wearing ceremonial dance costume

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Indians > Ceremonies and Customs >

Next: Legends • Contents • Previous: Life

The more than thirty individual villages and camp sites on the floor of Yosemite Valley were sharply divided into two classes in respect to the river, in accordance with the Miwok principle of totematic division; i.e., the Indians classified everything in nature as belonging to either the land or to the water side. The Grizzly Bear was the head of the land side; the Coyote the head of the water side. This division included not only the Indians themselves, but all other objects including even the stars. It was the custom of the man to always marry into the opposite division. In this manner in-breeding was kept to a minimum. Thus members of the Grizzly Bear moiety were assigned to the north side of the Merced River, and members of the Coyote moiety to the south side.

As stated previously, it is believed by some authorities that the name “Yosemite” which means “full-grown Grizzly Bear,” later came to be applied by outsiders to all of Tenaya’s people rather than to only the Grizzly Bear moiety on the north side of the river.

When an Indian fell ill, a shaman or medicine man was called to treat him. This Indian doctor, who was believed to have the powers of a clairvoyant, would dance, sing, and manipulate the patient. He then proceeded to suck the part of the body afflicted with pain, as a means of removing some religious taboo, or to dislodge a foreign object that had been placed there by a witch or wizard. Upon completion of this treatment, he would show the patient and relatives concerned a few hairs, a dead insect, or other foreign object to prove that he had been successful in removing the trouble. The psychological effect upon the patient when shown that the cause of his agony had been removed was most effective, and the relatives were satisfied that in a few days the patient would be well.

The Indians had great faith in the medicine man, but if he was unlucky enough to lose several patients, it behooved him to be concerned about his own life. The relatives of the deceased patients laid ever in wait for him in ambush, and unless he was able to escape to another locality, he was eventually murdered.

Cremation among the Indians was a common practice to liberate the spirit of the dead. To burn all of the belongings of the deceased at the cremation, excepting a few that were reserved for the annual mourning anniversary, was the usual procedure. All the mourners while dancing or crying around the cremation fire, threw some gift into the flames as cm offering of respect. When the body was consumed, the remains were gathered up and buried.

A widow cut her hair short with an obsidian knife, or burned it off. As a further symbol of grief, she smeared her face over with a weird ointment made of pitch and some of the ashes of her departed husband. Other near female relatives were also expected to so anoint themselves. This hideous mixture would sometimes cling to the face and clothing for six months, or even throughout the whole year of mourning, since it was disrespectful to wash it off.

In the late summer or autumn of each year, the Indians remembered their dead with a mourning ceremony. For several nights there were weeping, wailing, and singing around a campfire. At dawn on the last day of the ceremony, the mourners threw food into the fire for the spirits of their dead. Those who had lost loved ones during the year, fed the fire with the remainder of the deceased’s belongings, which had been saved from the cremation ceremony. As a symbol that the period of grief and its restrictions were over, the mourners cleansed themselves with water.

The Indians also celebrated their own Thanksgiving—an acorn celebration as a symbol of gratitude to the “Coyote Man,” an important diety of Miwok Indian mythology.

Lee-mee (Chris Brown) wearing ceremonial dance costume |

So far as is known, there are no full-blood Yosemites alive today. The Indians living in Yosemite are of mixed blood through inter-marriage with other tribes and races, mainly white and Mexican. Their mode of living is very similar to that of the whites in that they drive their own automobiles, have washing machines, radios, sewing machines, and most of the modern comforts and conveniences of civilized life.

Indian acorn-food |

Next: Legends • Contents • Previous: Life

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_indians/customs.html