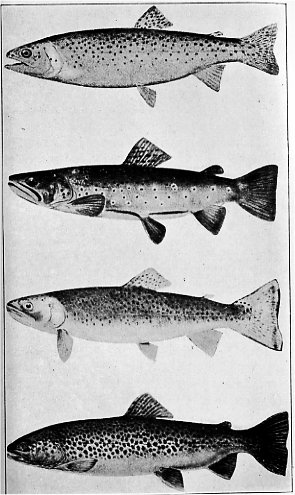

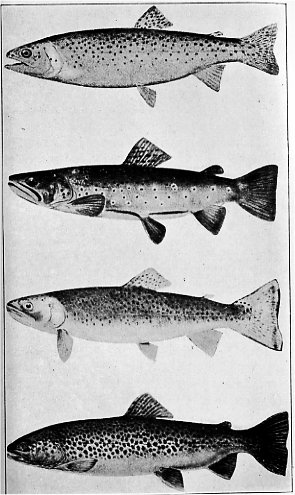

PLATE XIV

Some Trout of Yosemite National Park

Top to bottom—Rainbow Trout, Steelhead Trout, Eastern

Brook Trout, Golden (or Roosevelt) Trout

Pictures from California Fish and Game Commission

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Handbook > Fishes >

Next: Insects of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Reptiles and Amphibians of Yosemite

By Barton Warren Evermann

Director, Museum, California Academy of Sciences

The fish fauna of Yosemite National Park is not a rich one. Of native species there are two Suckers, three Minnows, and one Trout; and of these only the Trout is at all common. If we include the fishes not native to the region but which have been introduced into its lakes and streams, the number will be increased by nine additional species of Trout. The ten kinds of Trout in the park about in order of their relative abundance are:

Rainbow Trout; Salmo irideus GibbonsThis list includes most of the trout known from California waters.

Eastern Brook Trout; Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchill)

Shasta Trout; Salmo shasta (Jordan)

Loch Leven Trout; Salmo trutta levenensis (Walker)

Cutthroat Trout; Salmo clarkii Richardson

Steelhead Trout; Salmo gairdneri Richardson

Brown Trout; Salmo fario Linnaeus

Tahoe Trout; Salmo henshawi Gill & Jordan

Dolly Varden Trout; Salvelinus parkei (Suckley)

Golden Trout; Salmo roosevelti Evermann

The limited space available will permit only a very brief treatment of each species. It is hoped, however, at anyone interested can, with these short descriptions, identify with reasonable certainty the fishes he may find within the limits of Yosemite National Park.

In the first place, let it be said that all real trout of whatever kind, belong to the Salmonidae or Salmon Family. This family includes not only the true Trout but also the Salmons and the Charrs. Some of the species, usually the larger ones, are marine and anadromous, living most of their lives in the sea and Corning into freshwater streams only for spawning purposes. Others live habitually and continuously in the colder streams and lakes.

Of all the families of fishes there is none more interesting than the Salmonidae, from whatever point of view they may be considered. To the biologist, the family is of surpassing interest because of the remarkable life histories and habits of the many species; to the angler, no fish has appealed more strongly than the Salmon and Trout because of their game qualities and their beauty; to the epicure, there is none more delicious; to the lover of the beautiful as exhibited in animate forms, there is perhaps nothing that appeals more strongly than the silvery sheen, roseate or golden hugs, and the beautiful form of the Salmon, the Brook Trout, or the Golden Trout; to the fish culturist, the Salmonidae are of the greatest interest and importance, more species of this family being propagated artificially than of all other species combined; and to the commercial fisherman, this family of fishes is the most important in all the world.

The true Trout all belong to the genus Salmo and are found only in the northern parts of Asia, Europe, and North America; in Europe they extend as far south as the Pyrenees; and in America to Lower California

PLATE XIV Some Trout of Yosemite National Park Top to bottom—Rainbow Trout, Steelhead Trout, Eastern Brook Trout, Golden (or Roosevelt) Trout Pictures from California Fish and Game Commission |

California is richer in Trout than any other country in the world, the number of species or kinds now known from her lakes and streams being about a dozen.

It has been a more or less common practice to speak of the Trout of California as falling naturally into three series, popularly known as the Steelhead, Rainbow, and Cutthroat groups. This grouping is no longer accepted without reservations by ichthyologists. It has been shown that the Steelheads of California streams are simply Rainbows that have gone out to sea, and, after growing to considerable size and becoming silvery in color, have returned to fresh water, and that the Rainbows are simply the individuals that never went to sea. For present purposes, however, it seems best to treat them separately.

Salmo clarkii Richardson

Other names.—Red-throated Trout; Clark Trout; Black-spotted Trout; Clark Cutthroat Trout. Description.—The Cutthroat Trout can be readily known from all other trout by the red blotches on the membranes of the lower jaw. This mark is usually diagnostic of all the various species of so-called Cutthroat Trout, of which there are in western America not fewer than a dozen recognizable forms. These different forms may be distinguished from each other by proportional measurements, size of scales, and coloration. The Clark Trout is characterized by its fine scales and the presence of small teeth on the hyoid bone.

Distribution.—This species occurs in streams and lakes from the Columbia River south to northwestern California. It probably did not occur originally anywhere in the southern High Sierra, but it has been introduced into many streams and lakes. In Yosemite National Park it is most abundant in the Tuolumne River from Hetch Hetchy to its source, in the South Fork of the Merced, and in Gaylor and Peeler lakes.

Salmo henshawi Gill & Jordan

Other names.—Henshaw Trout; Black-spotted Trout; Truckee Trout; Silver Trout; Redfish; Tommy; Black Trout; Salmo tahoensis; Salmo purpuratus henshawi; Salmo mykiss henshawi; Salmo clarkii henshawi.

Description.—Color, dark olive-green above, body everywhere with rather widely scattered black spots, red darker on membranes of lower jaw; body stout, the greatest depth about one-fourth the total length; scales small.

Distribution.—This is the common trout of Lake Tahoe and its connecting waters; also of Donner, Webber, and Independence lakes and the upper part of Truckee River. It is not common in the park, but was introduced into the Tuolumne River at Hetch Hetchy Valley, Soda Springs, and in the Lyell Canyon in 1896. Habits.—During a portion of the year the Tahoe Trout lives in deep water, and can be caught, if at all, only on long lines. Early in the spring and in the summer, they are to be found in relatively shallow water. It may be that food supply accounts for, this migration, as spawning minnows seem to be the attractive food when the trout is in shallow water. The greatest number of this species are taken by trolling with a spoon. (Snyder.)

The Tahoe Trout appears to feed largely on minnows, but black ants and other insects are taken in quantity.

Salmo gairdneri Richardson

Other names.—Steelhead Trout; Steelhead Salmon; Salmon Trout; Hardhead.

Marks for field identification.—Large size; small head; large scales; bright silvery color; absence of red on lower jaw.

Distribution.—The Steelhead enters coastwise streams from Ventura northward, ascending to their headwaters for spawning purposes and then returning to the sea. Since 1917 the species has been introduced into Yosemite National Park in the Merced River and in Babcock, Emeric, Grant, Tenaya, and Ten lakes.

Habits.—The Steelhead is more or less anadromous in its habits, being migratory like the salmon and spending much of its time in salt water, and ascending freshwater streams at spawning time.

As a game-fish, the steelhead is a favorite with anglers. Its game qualities, together with its large size, make this one of the fishes most sought after by the followers of good old Isaak Walton. When in fresh water it will not only take the trolling spoon, but will rise readily to the fly. A The Steelhead is an excellent food-fish, and its large size and abundance make it of considerable commercial value. It is an important fish in the fish cultural operations of California and of other Pacific Coast states and of the Federal government. It has been introduced into Lake Superior and is now an abundant and much prized game-fish in that lake and its tributary streams.

The fact that most ichthyologists and many anglers regard Steelheads simply as sea-run individuals of Rainbow Trout has not escaped the writer’s attention, and he himself is inclined to accept the view. Nevertheless it is known that in some places, they are entirely distinct and easily distinguishable. At any rate, it is deemed best for present purposes to treat the Steelhead as a distinct species.

Salmo irideus Gibbons

Other names.—Mountain Trout; Speckled Trout; Brook Trout; California Trout; Sea-run form; Steelhead; Steelhead Trout; Steelhead Salmon; Salmon Trout; Salmo rivularis, in part; Salmo gairdneri, in part.

Description.—Body usually profusely covered with small roundish or star-shaped black spots, most numerous on back and upper part of side; middle of side with a rich rosy band; ground-color of back dark olive-green; fins all more or less spotted the dorsal, anal, and ventrals not usually tipped with white.

Distribution.—This is, as far as is known, the only native Trout in the Merced and Tuolumne rivers and their tributaries. It is very abundant in the park, having been introduced or transplanted into most streams and lakes in the Yosemite region. Locally the species is confused with its close relative, the Shasta Trout, which has been widely planted in the waters of the park under the name of Rainbow Trout.

Habits.—As a game fish the Rainbow Trout is one of the best. It runs upstream in early spring to spawn, leaping over waterfalls and entering the small streams forming the headwaters. Here the eggs are deposited in the sand and the young hatched out.

By far the largest output of the state hatcheries is composed of Rainbow Trout, and there is a good reason, for this is considered the best game-fish of all, and it is most highly prized by anglers. The Rainbow often leaves the water in its eagerness to take a fly. So readily does it take a fly, in fact, that there is seldom need to resort to bait or other lures.

The Rainbow varies in coloring according to age, sex, and location. Those individuals which are able to reach the sea spend part of each year there, return to the freshwater stream a larger and more silvery-colored fish commonly called Steelhead. Spawning fish travel far up the coastal streams and spawn high up in the small tributaries. Their habits in this regard are more like those of the salmon than those of the trout. Unlike the salmon, however, the Steelhead does not, as a rule, die after spawning.

In beauty of color, gracefulness of form and movement, sprightliness when in the water, reckless dash with which it springs from the water to meet the descending fly ere it strikes the surface, and the mad and repeated leaps from the water when hooked, the Rainbow Trout must ever hold a very high rank.

The gamest fish we have ever seen was a sixteen-inch Rainbow taken on a fly in a small tributary of the Williamson River in southern Oregon. It was in a broad and deep pool of exceedingly cool water. As the angler from behind a clump of willows made the first cast, the trout bounded from the water and met the fly in the air a foot or more above the surface; missing it, he dropped upon the water only to turn about and strike viciously a second time at the fly just as it touched the surface; though he again missed the fly, the hook caught him in the jaw from the outside, and then began a fight which would delight the heart of any angler. His first effort was to reach the bottom of the pool, then, doubling upon the line, he made three jumps from the water in quick succession, clearing the surface in each instance from one to four feet, and every time doing his utmost to free himself from the hook by shaking his head vigorously as a dog shakes a rat. Then he would rush wildly about in the large pool, now attempting to go down the riffle below the pool, now trying the opposite direction, and often striving to hide under one or the other of the banks. It was easy to handle the fish when the dash was made up or down stream or for the opposite side, but when he turned about and made a rush for the protection of the overhanging bank upon which the angler stood, it was not easy to keep the line taut. Movements such as these were frequently repeated and two more leaps were made. But finally he was worn out after as honest a fight as trout ever made.

The Rainbow takes the fly so readily that there is no reason for resorting to grasshoppers, salmon eggs, or other bait. It is a fish whose gameness will satisfy the most exacting of expert anglers and whose readiness

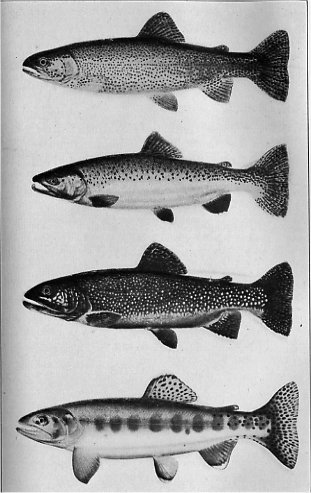

PLATE XV Some Trout of Yosemite National Park Top to bottom—Lake Tahoe Trout, Brown Trout, Cutthroat (or Black spotted) Trout, Loch Leven Trout Pictures from California Fish and Game Commission |

Spawning takes place in winter and early spring, varying with the temperature and locality. The bulk of the eggs are usually taken in February, March, and April, although spawning continues through May in the mountain districts.

The Rainbow feeds on worms, insect larvae, and salmon eggs. In streams in which the Salmon and Rainbow exist together, the Rainbow is more destructive to the salmon eggs than is any other species except the Dolly Varden.

Salmo shasta (Jordan)

Other names.—McCloud River Trout; McCloud River Rainbow; Shasta Rainbow; Rainbow Trout (of fish culturists); Salmo gairdneri shasta; Salmo irideus shasta.

Marks for field identification.—Differs from other Rainbow Trout, with the exception of that of the Klamath River, in its larger size, smaller mouth, and larger eyes; scales intermediate in size between Cutthroat and sea-run Rainbow, caudal fin more deeply incised than in typical Cutthroat.

Distribution.—McCloud River and streams of the Sierra Nevada from Mount Shasta southward at least to Calaveras County. This species has been widely introduced into the streams and lakes of Yosemite National Park where it is not officially distinguished from the true Rainbow.

Habits.—This Rainbow lives in water with a comparatively high temperature if it is plentiful and running with a strong current; but in sluggish water even when the temperature is considerably lower, no other species will do as well. This species appears to inhabit the rapids more largely than the slow-moving water. The spawning season in California extends from early February to May. Males are good breeders at two years of age, but the females rarely produce eggs until the third season. The Shasta Trout may lack a little of the wild gameness of the typical Rainbow, but that is made good by its larger size. It is largely an insect feeder and, therefore, a favorite of the fly fisherman.

This is the Rainbow which has been most widely used in fish cultural operations and has been more widely distributed than any other species.

The Golden Trout of California are, so far as known, found only in the headwaters of the Kern River, all in the vicinity of Mount Whitney. Through the activities of the California Fish and Game Commission and other agencies, their original distribution has been somewhat extended by transplanting.

Four species of trout are now recognized as native to the upper Kern River Basin, namely: The Kern River Trout or Gilbert Trout (Salmo gilberti), the Soda Creek or White’s Golden Trout (Salmo whitei), the South Fork of the Kern Golden Trout (Salmo agua-bonita), and the Roosevelt Trout or Golden Trout of Volcano Creek (Salmo roosevelti). All except the Gilbert Trout are of the Golden Trout type.

All four of these species belong to the Rainbow series, the species of which as a whole may be distinguished, with greater or less difficulty, from those of the Steelhead series or sea-run Rainbows on the one hand by the usually brighter colors, and on the other hand from the Cutthroat series, by the absence of a red or scarlet dash on the throat, and the entire absence of hyoid teeth.

Salmo roosevelti Evermann

Other names.—Roosevelt Trout; Golden Trout of Volcano Creek; Golden Trout of Golden Trout Creek; Volcano Creek Golden Trout; Mount Whitney Golden Trout.

Marks for field identification.—Color, delicate golden olive on the head, back, and upper part of the sides; clear golden yellow along and below the lateral line, overlaid by a delicate rosy lateral band; under parts rich cadmium yellow; body without black spots except on the caudal peduncle; scales extremely small.

Distribution.—The Golden or Roosevelt Trout is native only to Volcano Creek in the Mount Whitney region. It is a creek fish and appears to keep within the peculiar environment of this small stream. The species has been transplanted to and thrives in several near-by streams. In 1919 it was introduced into one of the unstocked lakes of Yosemite National Park.

Habits.—As a game-fish the Golden Trout is one of the best. It will rise to any kind of lure, including the artificial fly, at any time of day. In the morning and again in the evening, it will take the fly with a rush and make a good fight, jumping when permitted to do so; during the middle of the day it rises more deliberately and may sometimes be tempted only with grasshoppers. It is a fish that does not give up soon but continues the fight. Its unusual breadth of fins and strength of caudal peduncle, together with the turbulent water in which it dwells, enable it to make a fight equaling that offered by many larger trout.

The scales are smaller than in any other known species of trout. They are so small, indeed, as to have caused so good an observer as Stewart Edward White to declare that this trout had no scales at all.

Although now abundant in Volcano Creek, the Golden Trout cannot long remain so unless afforded some protection. The great beauty of the Roosevelt Trout lies in the richness of its colors and in the trimness of its form—characteristics which fully entitle the species to be known above all others as the Golden Trout.

Salmo fario Linnaeus

Other names.—European Brown Trout; German Brown Trout; von Behr Trout.

Marks for field identification.—This Trout can be distinguished from all other species by the decidedly brown color of the back and sides, the black spots on the back, and red spots on the sides; the belly is silvery or brownish.

Distribution.—The Brown Trout was introduced into the United States in 1895, and since then a number of streams in California have been stocked. In Yosemite National Park it may be taken in the Merced River, in the south Fork of the Merced River, and in Merced and Edna lakes.

Habits.—The Brown Trout lives in clear, cold, rapid streams and at the mouths of streams tributary to lakes. It grows to be of large size, but matures at about eight inches in length. In its movements it is swift, and it leaps over obstructions like the salmon. It usually feeds in the morning and evening, is more active during evening and night, and often lies quietly in deep pools or in the shadow of overhanging bushes and trees for hours at a time during the day. Its food is formed of insects and their larvae, worms, mollusks, and small fishes, and, like the Rainbow Trout, it is fond of the eggs of fishes. Spawning begins in October and continues until January. Eggs are deposited in crevices, between stones, under projecting roots of trees, and sometimes in nests excavated by the spawning fishes. The parents cover the eggs to some extent with gravel.

Salmo trutta levenensis (Walker)

Other names.—Scotch Trout; Salmo levenensis.

Marks for field identification.—The true Loch Leven Trout is a slimmer fish than the Brown Trout, and the adipose fin is smaller. Furthermore, it is fully spotted and lacks the brown color of the Brown Trout. The sides are silvery, with a varying number of X-shaped black spots or rounded brown or black spots.

Distribution.—This trout, a native of the lakes of Scotland, was introduced into California in 1894, and has since been placed in many streams and lakes of the State. Seventeen lakes of Yosemite National Park—among them the noted Benson, May, Merced, Washburn, and Ten lakes—have been stocked with this species. Fry have also been planted in the Merced and Tuolumne rivers.

Habits.—The spawning season may begin in October and continues until January. This trout is largely non-migratory in its native habitat. It takes the artificial fly readily. The food of this species includes freshwater mollusks, crustaceans, worms, and small fish. Hybridization between this species and the Brown Trout is common.

Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchill)

Other names.—Brook Trout; Speckled Trout; Fontinalis; Salmo fontinalis; American Charr.

Marks for field identification.—This beautiful and best-known trout is easily distinguished from all other trout of our waters by the red spots on the sides but not on the back, and the mottled or marbled color of the upper parts.

Distribution.—This trout is native only to the eastern part of North America westward to Minnesota and Iowa. It has been introduced very widely all over the world. It has been placed in many California streams and lakes and is one of the most abundant species in most streams and lakes of Yosemite National Park.

Habits.—Eastern Brook, Trout abound chiefly in cold, slow-running meadow brooks; but they thrive in all pure cold waters whether of stream, lake, or pond. The fish is wary and great skill is required to catch it. The outstanding peculiarity of its habits is evidenced by the fact that a person acquainted with its haunts can go out and catch a string of Eastern Brook in a comparatively short time, while others, with better tackle and equal skill, will fish a whole day for them in vain. The largest Brook Trout are found in the deep, wide pools in the warmer rivulets near their source. Eastern Brook Trout do not keep well nor ship well, probably on account of the fat. They spawn high up in tributary streams and so early (October to January) that eggs for hatchery purposes are almost impossible to obtain.

Salvelinus parkei (Suckley)

Other names.—Malma; Salmon Trout (Alaska and Montana); Bull Trout (Idaho); Western Charr; Oregon Charr; Salvelinus malma (in part).

Marks for field identification.—This fish may be readily distinguished from all other species of Salmonidae native to western America by the presence of small red or orange spots on the body. From the Eastern Brook Trout (introduced into many California waters) which also has red spots on the body, the Dolly Varden Trout may be known by the absence of blackish marblings or reticulations on the back, and by the presence of red spots on the back.

Distribution.—The Dolly Varden Trout is of wide distribution. It is found from western Montana and Idaho to Oregon and Washington, and northward through British Columbia and Alaska to the Arctic. In California it is native only to the McCloud River, but has been introduced into other streams. In Yosemite National Park the species is found only in one of the Chain o’ Lakes at the source of the South Fork of the Merced River and very rarely in the Merced River in Yosemite Valley.

Habits.—The Dolly Varden is the poorest of all trouts. It does not rank high as a game-fish, and, as a food-fish, it is inferior to any other species. In Alaska it is very destructive to the eggs and fry of the salmon. It attains a weight of two to twelve pounds.

. . . . . . .

This completes the list of Trout, both native and introduced, that are found in Yosemite National Park. There remain but two suckers and three minnows that might be found within the park limits. The Sacramento or Western Sucker (Calostomus occidentalis) is common in the lower reaches of all streams of the State, but the Hardhead Sucker (Pantosteus araeopus) is a very rare species. Of the three species of Minnows, the first is the Kaweah Chub, Lake Fish, or Hardhead (Mylopharodon conocephalus), one of the largest of Minnows. It reaches a length of two or three feet and a weight of several pounds. The next Minnow is the Sacramento Pike or Squawfish (Ptychocheilus grandis). This fish, which reaches a length of two or three feet, is abundant in the lower portions of all the larger tributaries of the San Joaquin. Still another minnow is the Chub (Siphateles formosus), a small species, usually not exceeding four or five inches in length. So far as the writer knows none of these minnows or suckers has been recorded from any locality within the limits of Yosemite National Park.

Evermann, Barton Warren, 1906. The Golden Trout of the Southern High Sierras. Bull. Bureau Fisheries, Vol. 25, pp. 1-51, 3 colored plates, 45 half tones, and one map.

Evermann, Barton Warren, and Bryant, Harold C., 1919. California Trout. California Fish and Game, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 105-135, 4 colored plates and 13 half tones, July, 1919.

Jordan, David Starr, and Evermann, Barton Warren, 1896.

A Check-list of the Fishes and Fish-like Vertebrates of North and

Middle America. Rept. U.S. Fish Com. for 1895, Vol. 21,

pp. 207-584.

1896-1900. The Fishes of North and Middle America. Bulletin

47, U. S. National Museum, 4 vols., pp. ccxv+3313,

pls. 392.

1902. American Food and Game Fishes. (Doubleday, Page

& Co., Garden City, N. Y.) pp. 1+572, with numerous

colored plates, half tones, and text figures.

Next: Insects of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Reptiles and Amphibians of Yosemite

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/handbook_of_yosemite_national_park/fishes.html