| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Discovery >

Next: Chapter 3 • Index • Previous: Chapter 1

|

I am not covetous for gold;

Nor care I who doth feed upon my cost; It yearns me not if men my garments wear; Such outward things dwell not in my desires; But if it be a sin to covet honor I am the most offending soul alive.

—Shakespear’s

Henry V., Act IV.

|

|

Tender-handed stroke a nettle,

And it stings you for your pains; Grasp it like a man of mettle, And it soft as silk remains.

—Aaron Hill,

written upon a window in Scotland.

|

After the discovery of gold at Sutter’s saw-mill, Coloma, California, January 19, 1848, by James W. Marshall—who died, poor, August 10th, 1885, at the age of 73 years—and the news of that auspicious event had winged its electrifying flight to the farthest corner of the civilized world, men, filled with ambitious hopes and yearnings, began to flock towards the new El Dorado from every clime and country. The beautiful and land—locked Bay of San Francisco was soon plowed by the prows of vessels of every class and tonnage, and its recently uneventful calm broken by the health—giving breezes of a new and vigorous commercial activity.

“Awake but one, and lo! what myriads rise!

Each stamps its image as the other flies!”

The streets of the sleeping pueblo of San Francisco, filled by the in-flowing tide of humanity thus attracted, awoke it at once to a business energy that eventually grew into a habit, and laid the foundation of its present commercial prosperity.

Feverish with enlarged expectations, and eager to realize the day-dreams of their susceptible imaginations, any and every kind of conveyance, by water or by land, was pressed into immediate service, for speeding them to the gold mines. Discomfort, exposure, pleasure postponed, disappointment, suffering, danger, and possible sickness or prospective death, held them in no restraint; like the proverbial youth who had heard in his native village that the streets of a certain city were paved with gold, would give himself no rest, either day or night, until it could be reached, and “a hat full of it” obtained.Beguiled by this fascination, that became almost an infatuation, side-hills and flats, ravines and gulches, cañons and rivers, threading far among the spurs of the Sierras, became familiar to the footsteps of the dauntless prospector. Unbroken solitudes, untrodden fastnesses, far from civilized habitation or human succor, created in him no sense of fear, or thought of peril. The occasional sight of Indians, whether singly or in groups, evoked no surprise, invited no uneasiness, and elicited no suspicion. A casual, perhaps an inquisitive glance, might occasionally be thrown over the shoulder of the one to the other in indifferent recognition as they passed; but that was in no way to be interpreted as unfriendly. In time, presents of food and cast-off garments apparently became

Between civilized and savage, and seemingly bound their common interests closer together. The absence even of grunted gratitude for favors received, excited no comment, and quickened no resentment. Civilities and gratuities imperceptibly indicated the opening of a broader pathway to mutual confidences and con cessions between whites and Indians, that left no doubt of ultimate harmonious concert of action. Meanwhile,

“The greatest of the angels of men—Success"—

Had crowned the gold miner’s efforts in unearthing the precious metal. This attracted a rapidly increasing multitude of devotees to its captivating standard; and men poured in from every quarter, to enlist under its enchanting banner, and in full chorus to sing around their camp-fires:—

“’Tis time the pick-axe and the spade,

Against the rocks were ringing,

And with ourselves the golden stream

A song of labor singing;

The mountain sod our couch at night;

The stars keep watch above us;

We think of home, and fall asleep—

To dream of those who love us.”

The good fortune and wants of the miner developed the necessity for the packer and trader, with their assistants; and, as a sequence, kept constantly swelling the army of occupation in the very haunts and homes of the Indian; and without invitation divided with him his hunting and fishing grounds. Tents pitched and cabins erected, became sufficient foundation for the impression that the new-comers were intending permanently to stay. There seems to have been no expressed or implied objections to this. The Indian men, moreover, had been pressed into willing service as miners and laborers, and the women to laundry work—for which, in many instances, they were liberally paid. All of these very naturally gave color to the assurance that a mutually advantageous community of interests had spring up that was as gratifying as it was profitable. But these eventually proved to be

The rapid increase of horses, mules, and cattle—as well as men—presented visible evidences of accumulating prosperity and wealth among the whites, that were unshared by the Indian. This soon bore the poisonous fruit of jealousy. Germs of unrest and discontent quickly ripened into resentment; and, with steal thy growth, hatred for the whites and cupidity for their possessions began, irrepressibly, to extend to every mountain tribe throughout the State, and prepare the way for openly hostile demonstrations. It is however but

To the Indian, here to record—without in any measure at tempting to apologize for, or condone, his misdeeds—that the spirit of reciprocal fairness was not an invariable characteristic of the whites, in their dealings and conduct with the inferior race. Every old Californian can bear blushing testimony to the truthfulness of this too self-evident admission. This will be more than manifest from the official report of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Green, to Gov. Peter H. Burnett, dated May 25, 1850,* [* See page 769 of Journals of the Legislature of California, for 1851.] as follows: “Heretofore a few persons have monopolized much of their labor, by giving them a calico shirt per week, and the most indifferent of food.” Brig. Gen. Thomas B. Eastland, in his report to his excellency Governor Burnett, dated June 15, 1850† [† Page 770, Ibid.] thus continues: “It is a well-known fact that among our white population there are men who boast of the number of the Indians they have killed, and that not one shall escape.” If, therefore,

“In men we various Ruling Passions find,

And Ruling Passion conquers Reason still.”

No spirit of prophetic divination need be evoked, to foretell the ultimate results of such aggressive wrong-doing. Before pouring unmixed anathemas, therefore, upon the Indian’s head, will not an intuitive sense of right first prompt us to

“Find out the cause of this effect;

Or, rather, say, the cause of this defect;

For this effect defective comes by cause.”

| |

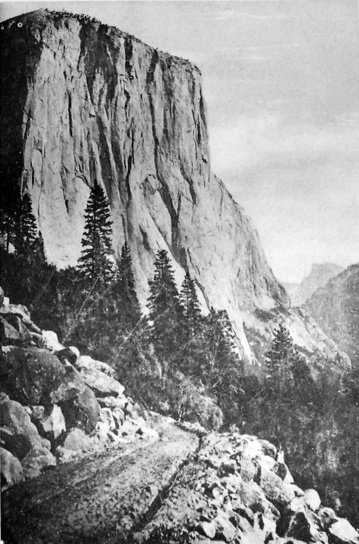

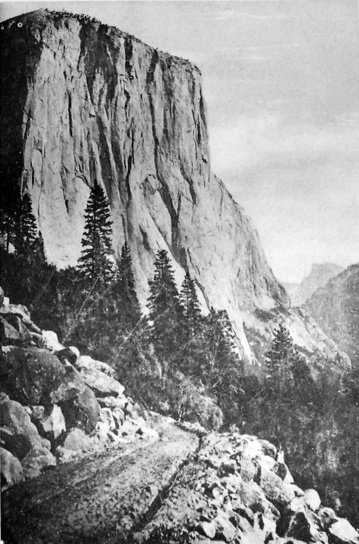

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| El Capitan, Half Dome, and Valley. | |

| From Big Oak Flat Road. | |

In the days of their numerical prosperity, moreover, it should be remembered that the Indians thoroughly understood and practiced a primitive method of telegraphing by fire and smoke, by which the fitful flashes of the one, and the gusty clouds of the other,‡ [‡ This was done by covering a large fire with a wet hide, and lifting it at intervals.] according to the number or the intensity of the signals given, would readily communicate the kind of trouble they were in, and the nature of the assistance they required. All prominent peaks, and favorable points of bluffs on the margin of valleys, were signal stations; and there was always a signal watcher on duty, both by day and by night. To this was supplemented a very

Composed of their best-trained, swiftest-footed, and strongest lunged young men, who would run at the height of their speed from one village to the other. These advantages naturally and effectively supplied speedy tribal communication, and enabled them not only to discuss with each other the social or political significance of such an unparalleled influx of strangers amongst them, but to report every overt act or aggressive movement of the whites, from San Diego to Siskiyou.

Had been early reported from central portions of the State, but as these had been visited by swift retaliation, the impetuously turbulent were, for the time being at least, checked in their marauding and murderous career. Meanwhile the forces of their enmity were silently cumulating, like a storm over an almost cloudless sky, in the more southerly sections of California; eventually to culminate and break among the gold mines of Mariposa County—then very large, and embracing the counties now known as Mariposa, Merced, Fresno, Ware, Mono, and Inyo.

Was led by the Yo Semites, in May, 1850, when an attack was made upon the trading-post of Mr. James D. Savage, located on the Merced River, about twenty-five miles below the Yo Semite Valley, under the pretense of claiming all the country in that vicinity; but in reality in the expectation and hope of plunder. By the personal pluck and energy of Savage, assisted by his Indian miners, the attack was successfully repulsed.

The isolation of that station, and the known murderous tendencies of the Yo Semites, induced Savage to remove his store to Mariposa Creek, near Agua Fria, some six miles westerly of the village, now the prosperous town and county seat, of Mariposa. His unexampled success in this new location tempted him to establish a branch post on the Fresno River, which also gave abundant promise of similar results. “In the midst of renewed prosperity"—says Dr. L. H. Bunnell, in his interesting narrative of “The Discovery of the Yosemite,” from which I shall frequently quote in introductory chapters, and to which I heartily refer the reader—”he learned that

“To strengthen his influence over the principal tribes, Savage had, according to the custom of many mountain men at that time, taken wives from among the Indians, supposing that his personal safety would be somewhat improved by so doing. This is the old story of the prosperous Indian trader. One of his squaws assured him that a combination was maturing among the mountain Indians to kill or drive all the white men from the country, and plunder them of their property.” These unmistakable evidences of threatened hostilities suggested the adoption of precautionary measures, and preparation for warlike surprises, without exciting suspicion or alarm. In the hope of averting impending danger,

Having to visit San Francisco early in the ensuing September (1850) for the purpose of securing a safe place of deposit for his rapidly accumulating quantities of gold-dust, extracted from the mines by himself and his Indian assistants, and received through his stores,* [* The amount, as given by reliable authority, was about six hundred pounds, Troy. As an illustrative example of one of Savage’s habits, and an additional proof of the old adage, “Easily earned—carelessly spent.” after his safe arrival in San Francisco with his treasure, he sought the gaming-table, where he became a heavy loser; as though reckless of consequences, he jumped upon the card table, and, standing upon a Particular card, wagered his own weight in gold-dust on that card—and lost! ] and also to purchase goods, he concluded to take with him two of his Indian wives, and an influential Indian chief named Jose Juarez,* [* A name probably given him at one of the old missions.] that by showing them the overwhelming numbers and resources of the whites, he could impress upon them, and through them all the unfriendly disposed, the utter hopelessness of any bellicose movements on their part. This skillfully-planned stratagem, although substantially carried out by Savage, was

Inasmuch as Jose, having been liberally supplied with money by his generous patron, invested it as liberally in “fire water;” and, under its influence, became either stupidly unconscious or insultingly abusive. Remonstrance only stimulated a more emphatic indulgence in that graceless vice. When forbearance had ceased to be a virtue, and the wanton gratification of insulting epithets had reached their climax, in an unguarded moment, Savage felled him with a blow. This invited, and probably deserved punishment, was a source of constant subsequent regret; but, as the journey homeward developed no signs of any vengeful remembrances, it was hoped that the unpleasant incident had been either over looked or excused. Therefore, nothing doubting in that, or in the happy results of Jose’s visit to the larger cities, as numerous Indians had collected around his Fresno store, seemingly to welcome them on their arrival, and to compare notes, and learn or tell the news, Savage concluded this to be

About the sights they had seen, with a view of conciliating their prejudices—if any still existed—and convincing their judgments of the relative advantages that would naturally arise from a good understanding between the whites and the Indians. After presenting the case in a strikingly terse and forcible manner, Savage called upon Jose to bear testimony to the truthfulness of his explanations, and the undoubted strength of his arguments. To his surprise, however, “The cunning chief, with much dignity"—I again quote from Doctor Bunnell—”deliberatively stepped forward, with more assurance than he had shown since the belligerent occurrence at San Francisco, and spoke with more energy than Savage had anticipated, as follows:—

“’Our brother has told his Indian relatives much that is true; we have seen many people; the white men are very numerous; but the white men we saw are of many tribes; they are not like the tribe that digs gold in the mountains. They will not help the gold-diggers, if the Indians make war against them. If the gold-diggers go to the white tribes in the big village they give their gold for strong water, and games; when they have no more gold the white tribes drive the gold-diggers back to the mountains with clubs. They strike them down’ (referring to the police) ‘as your white relative struck me when I was with him.’ (His vindictive glance assured Savage that the blow was not forgotten or forgiven.)’ The white tribes will not go to war with the Indians in the mountains. They cannot bring their big ships and big guns to us; we have no cause to fear them. They will not injure us.’”

This was followed by a glowingly humorous and sarcastic picture of the pale faces, their tall hats, walking canes, eyeglasses, fancy clothes, and other supposed frivolous articles of the toilet; and the manners and customs of white people in large cities were so grotesquely mimicked that he frequently convulsed his Indian auditors with laughter, broken occasionally with guttural utterances of contempt.

No replying arguments of Savage, filled to overflowing as they were with kindness and common sense, could counteract the magical effects of such a speech. But, fearing that they might, Jose again stepped forward, and

By exclaiming,* [* Dr. L. H. Bunnell. ] “He is telling you words that are not true. His tongue is forked and crooked. He is telling lies to his Indian relatives. This trader is not a friend to the Indians. He is not our brother. He will help the white gold-diggers to drive the Indians from their country. We can now drive them from among us; and if the other white tribes should come to their help, we will go to the mountains; if they follow us they cannot find us; none of them will come back; we will kill them with arrows and with rocks.’” These war-like utterances of Jose Juarez were warmly seconded by

In the following speech, also reported by Dr. Bunnell: “My people are now ready to begin a war against the white gold-diggers. If all the tribes will be as one tribe, and join with us, we will drive all the white men from our mountains. If all the tribes will go together, the white men will run from us, and leave their property behind them. The tribes who join in with my people will be the first to secure the property of the gold-diggers.”

“The dignified and eloquent style of Jose Rey,” continues Dr. Bunnell, “controlled the attention of the Indians. This appeal to their cupidity interested them; a common desire for plunder would be the strongest inducement to unite against the whites. Savage was now fully aware that he had been defeated at the impromptu council he had himself organized, and at once withdrew to prepare for the hostilities he was sure would follow. As soon as the Indians dispersed, he started with his squaws for home, and again gave the settlers warning of what was threatened, and would soon be attempted.

“These occurrences were narrated to me by Savage. The incidents of the council at the Fresno Station were given during the familiar conversations of our intimate acquaintance. The Indian speeches here quoted are, like all others of their kind, really but poor imitations. The Indian is very figurative in his language. If a literal translation were attempted, his speeches would seem so disjointed and inverted in their methods of expression that their signification could scarcely be understood; hence only the sub stance is here given.”

It would seem that, notwithstanding the warnings given, the miners and settlers were unwilling to concede that an Indian war was possible, even with such conclusive evidence

“To mark the signs of coming mischief,”

As they were deemed as absurd as they were improbable. Even Cassady, a rival trader to Savage, “especially scoffed at the idea of danger, and took no precautions to guard himself or his establishment"—and was afterwards among the first murdered.

In their minds there evidently lingered a doubt, and perhaps with it a mental questioning whether or not

“The chance of war

Is equal, and the slayer oft is slain,”

As active hostilities did not actually commence until the middle of December following. This will be apparent from an official letter by Col. Adam Johnston, sub. Indian Agent of the United States, under Gen. John Wilson, and addressed to His Excellency, Peter H. Burnett, then Governor of California; and as it is not only an interesting narrative, but lucidly explanatory, it is here transcribed.

San Jose, January 2, 1851.*

Sir: I have the honor to submit to you, as the Executive of the State of California, some facts connected with the recent depredations committed by the Indians, within the bounds of the State, upon the persons and property of her citizens. The immediate scenes of their hostile movements are at and in the vicinity of the Mariposa and Fresno. The Indians in that portion of your State have, for some time past, exhibited disaffection and a restless feeling toward the whites. Thefts were continually being perpetrated by them, but no act of hostility had been committed by them on the person of any individual, which indicated general enmity on the part of the Indians, until the night of the 17 December last. I was then at the camp of Mr. James D. Savage, on the Mariposa, where I had gone for the purpose of reconciling any difficulty that might exist between the Indians and the whites in that vicinity. From various conversations which I had held with different chiefs, I concluded there was no immediate danger to be apprehended. On the evening of the 17th of December, we were, however, surprised by the sudden disappearance of the Indians. They left in a body, but no one knew why, or where they had gone. From the fact that Mr. Savage’s domestic Indians had forsaken him and gone with those of the rancheria, or village, he immediately suspected that something of a serious nature was in contemplation, or had already been committed by them.

The manner of their leaving, in the night, and by stealth, induced Mr. Savage to believe that whatever act they had committed or intended to commit, might be connected with himself. Believing that he could over haul his Indians before others could join them, and defeat any con templated depredation on their part, he, with sixteen men, started in pursuit. He continued upon their traces for about thirty miles, when he came upon their encampment. The Indians had discovered his approach and fled to an adjacent mountain, leaving behind them two small boys asleep, and the remains of an aged female, who had died, no doubt from fatigue. Near to the encampment Mr. Savage ascended a mountain in pursuit of the Indians, from which he discovered them upon another mountain at some distance. From these two mountain tops, conversation was commenced and kept up for some time between Mr. Savage and the chief, who told him they had murdered the men on the Fresno, and robbed the camp. The chief had formerly been on the most friendly terms with Savage, but would not now permit him to approach him. Savage said to them that it would be better for them to return to their villages—that with very little labor daily they could procure sufficient gold to purchase them clothing and food. To this the chief replied it was a hard way to get a living, and that they could more easily supply their wants by stealing from the whites. He also said to Savage he must not deceive the whites by telling them lies, he must not tell them that the Indians were friendly, they were not, but on the contrary were their deadly enemies, and that they intended killing and plundering them so long as a white face was seen in the country. Finding all efforts to induce them to return, or to otherwise reach them, had failed, Mr. Savage and his company concluded to return. When about leaving, they discovered a body of Indians, numbering about two hundred, on a distant mountain, who seemed to be approaching those with whom he had been talking.

Mr. Savage and company arrived at his camp in the night of Thursday, in safety. In the meantime as news had reached us of murders committed on the Fresno, we had determined to proceed to the Fresno, where the men had been murdered. Accordingly, on the day following, Friday, the 20th, I left the Mariposa camp, with thirty-five men, for the camp on the Fresno, to see the situation of things there, and to bury the dead. I also dispatched couriers to Agua Fria, Mariposa, and several other mining sections, hoping to concentrate a sufficient force on the Fresno to pursue the Indians into the mountains. Several small companies of men left their respective places of residence to join us, but being unacquainted with the country, they were unable to meet us. We reached the camp on the Fresno a short time after daylight. It presented a horrid scene of savage cruelty. The Indians had destroyed everything they could not use, or carry with them. The store was stripped of blankets, clothing, flour, and everything of value; the safe was broken open and rifled of its contents; the cattle, horses, and mules had been run into the mountains; the murdered men had been stripped of their clothing, and lay before us filled with arrows; one of them had yet twenty perfect arrows sticking in him. A grave was prepared, and the unfortunate persons interred. Our force being small, we thought it not prudent to pursue the Indians further into the mountains, and determined to return. The Indians in that part of the country are quite numerous, and have been uniting other tribes with them for some time. On reaching our camp on the Mariposa, we learned that most of the Indians in the valley had left their villages and taken their women and children to the mountains. This is generally looked upon as a sure indication of their hostile intentions. It is feared that many of the miners in the more remote regions have already been cut off, and Agua Fria and Mariposa are hourly threatened.

Under this state of things, I come here at the earnest solicitations of the people of that region, to ask such aid from the State Government as Will enable them to protect their persons and property.

I submit these facts for your consideration, and have the honor to remain. Yours very respectfully,

Adam Johnston.

To His Excellency,

Peter H. Burnett.

Upon the morning above mentioned in Colonel Johnston’s letter, according to the testimony of Mr. Brown, the only survivor of the massacre, straggling groups of Indians, unattended by women and children, contrary to usual custom when on a peaceful mission, commenced wending their way, saunteringly, from different directions, towards Savage’s store upon the Fresno. They entered it in their ordinary listless manner, as though for purposes of trade; but, when within it, by some evidently preconcerted plan of attack, they sprang simultaneously forward, and with hatchets, axes, crow-bars, and bows and arrows, first murdered Mr. Greeley, who was in charge of the store; then, turning upon the three other white men there present, named Canada, Stiffner, and Brown, killed all except the latter, whose life was saved by an Indian named Polonio,* [* So christened by the whites probably from some peculiar characteristic of his.] to whom Brown had shown favors, jumping in between him and the attacking party, at the risk of his own personal safety, thus affording Brown the chance of escape, of which he confesses to have made the best use, by running all the way to Quartzburg at the top of his speed. Thereafter horses, mules, and cattle belonging to the whites, began to disappear, cabins were broken open and despoiled in the absence of their owners; solitary prospectors were waylaid, robbed, and murdered; isolated settlers, and secluded miners delving in some far off and shadowy cañon, unsuspicious of active race antagonisms, were sought out, overpowered, and slaughtered in cold blood. The perpetrators of these satanic crimes, going undetected and unpunished, for a time reveled in a frenzy of diabolical excesses.

Simultaneously with these outrages, Savage’s other store and residence on the Mariposa, after the sudden disappearance of the resident Indians, as given in Colonel Johnston’s letter, were attacked, during the absence of the proprietor, and everything stolen. Similar onslaughts having been made at various points on the Merced, San Joaquin, Fresno, and Chow-chilla Rivers, it be came too painfully evident that a general Indian war was being forced upon the whites.

In this emergency Maj. James Burney, Sheriff of Mariposa County, and Mr. James D. Savage, the trader, with other prominent citizens, immediately commenced to raise a company of volunteers, and at once led it into active and efficient service. As experiences of this courageous little band are graphically told by Major Burney, in a letter to His Excellency, John McDougal, Governor of the State, and emphatically certified to and indorsed by Hon. J. M. Bondurant, County Judge, and Richard H. Daly, County Attorney, no apology will be necessary for introducing it entire, from the Legislative Journals of California for 1851.

Agua Fria, January 13, 1851.

Sir: Your Excellency has doubtlessly been informed by Mr. Johnston,* [* Col. Adam Johnston.] and others, of repeated and aggravated depredations of the Indians in this part of the State. Their more recent outrages you are probably not aware of. Since the departure of Mr. Johnston, the Indian Agent, they have killed a portion of the citizens on the head of the San Joaquin River, driven the balance off, taken away all the movable proper ty, and destroyed all they could not take away. They have invariably murdered and robbed all the small parties they fell in with between here and the San Joaquin. News came here last night that seventy-two men were killed on Rattlesnake Creek; several men have been killed in Bear Valley. The Fine Gold Gulch has been deserted, and the men came in here yesterday. Nearly all the mules and horses in this part of the State have been stolen, both from the mines and the ranches. And I now in the name of the people of this part of the State, and for the good of our country, appeal to Your Excellency for assistance.

In order to show Your Excellency that the people have done all that they can do to suppress these things, to secure quiet and safety in the possession of our property and lives, I will make a brief statement of what has been done here:—

After the massacres on the Fresno, San Joaquin, etc., we endeavored to raise a volunteer company to drive the Indians back, if not to take them or force them into measures. The different squads from the various places rendezvoused not far from this place on Monday, 6th [December, 1850], [Editor’s note: the correct date is Monday January 6, 1851, not December, 1850, as inserted by Hutchings. December 6th 1850 falls on a Friday and is inconsistent with other events in December 1850. For more information, see Bunnell Discovery of the Yosemite chapter 2.—dea] and numbered but seventy-four men. A company was formed, and I was elected Captain; J. W. Riley, First Lieutenant; E. Skeane, Second Lieutenant. We had but eight days’ provisions, and not enough animals to pack our provisions and blankets, as it should have been done. We, however, marched, and on the following day struck a large trail of horses that had been stolen by the Indians.† [† In a subsequent letter of Major Burney, addressed to the Hon. W. J. Howard, Occurs the following passage:— “The first night out you came into my camp and reported that the Indians had stolen all your horses and mules—a very large number—that you had followed their trail into the hill country, but, deeming it imprudent to go there alone, had turned northward, hoping to strike my trail, having heard that I had gone out after Indians. I immediately, at sunset, sent ten men (yourself among the number) under Lieutenant Skeane—who was killed in the fight next day—to look out for the trail, and report, which was very promptly carried out."] I sent forward James D. Savage, with a small spy force, and I followed the trail with my company. About two o’clock in the morning, Savage came in and reported the village near, as he had heard the Indians singing. Here I halted, left a small guard with my animals, and went forward with the balance of my men. We reached the village just before day, and at dawn, but before there was light enough to see how to fire our rifles with accuracy, we were discovered by their sentinel. When I saw that he had seen us, I ordered a charge on the village (this had been reconnoitered by Savage and myself). The Indian sentinel and my company got to the village at the same time, he yelling to give the alarm. I ordered them to surrender; some of them ran off, some seemed disposed to surrender, but others fired on us; we fired, and charged into the village. Their ground had been selected on account of the advantages it possessed in their mode of warfare. They numbered about 400, and fought us three hours and a half. We killed from 40 to 50, but cannot tell exactly how many, as they took off all they could get to. Twenty-six were killed in and around the village, and a number of others in the chaparral. We burned the village and provisions, and took four horses. Our loss was six wounded, two mortally; one of the latter was Lieutenant Skeane, the other a Mr. Little, whose bravery and conduct through the battle cannot be spoken of too highly.

We made litters, on which we conveyed our wounded, and had to march four miles down the mountain, to a suitable place to camp, the Indians firing at us all the way, from the peaks on either side, but so far off as to do little damage. My men had been marching or fighting from the morning of the day before, without sleep, and with but little to eat. On the plain, at the foot of the mountain, we made a rude, but substantial fortification; and at a late hour those who were not on guard were permitted to sleep. Our sentinels were (as I anticipated they would be) firing at the Indians occasionally all night, but I had ordered them not to come in until they were driven in.

I left my wounded men there, with enough of my company to defend the little fort, and returned to this place for provisions and recruits. I send them to-day reinforcements and provisions, and in two days more I march by another route, with another reinforcement, and intend to attack another village before going to the fort. The Indians are watching the movements at the fort, and I can come up in the rear of them unsuspectedly, and we can keep them back until I can hear from Your Excellency.

If Your Excellency thinks proper to authorize me or any other person to keep this company together, we can force them into measures in a short time. But if not authorized and commissioned to do so, and furnished with some arms and provisions, or the means to buy them, and pay for the services of the men, my company must be disbanded, as they are not able to lose so much time without any compensation.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

James Burney.

This battle took place upon the upper waters of the Fresno; and notwithstanding the measurable success of this hastily planned and impetuous attack, there is no reason to fear that, owing to the absence of efficient discipline and drill, in so rapidly mustered a company of volunteers, but for the dauntless pluck and daring of this heroic band, it would have been a defeat. Nothing but reckless personal exposure, and hand-to-hand conflict, eventually brought a partial victory. After the conflict they were abundantly willing to retire to camp for rest, council, reorganization, and future discipline; and the experience gained proved to be of inestimable value in the future conduct of the war.

From apparently sympathetic anticipation of the sentiments and wants expressed in Major Burney’s manly letter, His Excellency, Governor McDougal (having through Col. Adam Johnston’s official communication, and other sources, already received information of the struggle progressing in Mariposa County), had issued an order—by a singular coincidence bearing exactly the same date, January 13, 1851,* [* See Journals of the Legislature of California for 1851, page 600.] as Major Burney’s letter—authorizing the Sheriff of Mariposa County to call out one hundred able-bodied militia, with which to meet the pressing exigencies of the times, and teach the Indians that, while the whites could be considerate of their interests in times of peace, they were prepared at all hazards to assert and maintain their rights the moment that war was forced upon them.

To this prompt and considerate action was supplemented an appealing message from Governor McDougal to the State Legislature, then in session, calling upon it for means to meet such pressing emergencies; a communication addressed to the Indian Commissioners, appointed by the General Government for co-operation; and to General Persifer S. Smith, commanding Pacific Division of the United States Army, informing him of the Indian disturbances, of his official orders calling out two hundred able bodied militia, and asking him what aid might be expected from his department, the number of effective troops to be relied on, whether there could be furnished arms and ammunition to volunteers, and if so the character and number of arms and ammunition, and concluding with the question, “Will you deem it advisable to co-operate in the present emergency?"* [To this inquiry there seems to have been no response published—at least none can be found by the writer. It is however matter of record that the State assumed the responsibility for the disbursements of this war, but the expenses were afterwards allowed by the United States Government.]

Without awaiting a reply from Gen. P. F. Smith, such was the anxiety of the Governor lest any omission on his part should cause an unnecessary sacrifice of human life and property, he dispatched Col. J. Neely Johnson, an officer of his staff, to the United States Indian Commissioners, Messrs. Wozencraft, McKee, and Barbour, with offers of safe-conduct to the scene of the disturbances, accompanied with the assurance that “Colonel Johnson will afford you with every facility in his power to co-operate with you in all measures necessary to insure a return of those friendly feelings which are so desirable to us, and so essential to the happiness of both whites and Indians.” Too much commendation of Governor McDougal’s praiseworthy and intelligent assiduity cannot well be accorded him, not only for his unwearying watchfulness, but for providing the “sinews of war,” as well as for his continuous efforts to establish an early and enduring peace.

The Governor’s offer was cordially accepted by the United States Indian Commissioners, who, under the escort of Col. J. Neely Johnson and a small body of State troops, as related else where, set out on their peaceful mission as soon as possible, after securing the services of some friendly mission Indians, as interpreters and messengers, and the providing of suitable presents and supplies. While they are repairing thither, let us return, at least in imagination, to the camp of the volunteers.

In the interim of Major Burney’s absence at the settlements, for munitions and reënforcements, no time was lost by the little corps remaining at their post among the Indians, in drilling, reörganizing, and otherwise preparing for future contact with the foe. Growing tired, however, of the commonplace inactivities of camp life, and longing for the excitements attendant on an en counter with the enemy, but a few restful days were allowed to pass before they were again upon the march.

The Indian trail was soon struck, and upon the top of a rugged knoll, near the north fork of the San Joaquin River, surrounded by a dense undergrowth of shrubbery, among rocks and trees, they found the adversary in force, apparently numbering about five hundred. Defiant taunts of their late defeat, intermixed with sneering accusations of cowardice, were menacingly hurled at the whites; and the Indians even boasted of their robberies and murders, and challenged Savage, who was then in command, to come up and fight them. But as it was late in the day when the Indians were discovered, and feeling, with Shakespeare, that

“The better part of valor is discretion,”

Instead of commencing an immediate attack, a careful reconnoissance was made before nightfall, and the assault postponed.

Almost before morning light revealed the position of their antagonists, thirty-six men were detached for preliminary operations, under Captain Kuykendall, to be followed by the reserves, under Major Savage and Captain Boling—and fortunately the Indian camp was reached by Kuykendall’s command without discovery. Dashing into their midst, and seizing lighted brands from their own camp-fires, the wigwams were set on fire, and, by their light, they attacked the now alarmed camp. So rapidly and so bravely were the charges made that the panic-stricken warriors fled precipitately from their stronghold. “Jose Rey was among the first shot down,” says Dr. Bunnell. “The Indians made a rally to recover their leader; Lieutenant Chandler, observing them, shout ed, ‘Charge, boys! Charge!!’ when the men rushed forward, and the savages turned and fled down the mountain, answering back the shout of Chandler by replying, ‘Chargee! Chargee!’ as they disappeared. The whole camp was routed, and sought safety among the rocks and brush, and by flight. This was an unexpected result. The whole transaction had been so quickly and recklessly done that the reserves under Boling and Savage had no opportunity of participating in the assault, and but imperfectly witnessed the scattering of the terrified warriors. Kuykendall, especially, displayed a coolness and valor entitling him to command—though outrun by Chandler in the assault. The fire from the burning village spread so rapidly down the mountain side towards our camp as to endanger its safety. While the whites were saving their camp supplies, the Indians, under cover of the smoke, escaped. No prisoners were taken; twenty-three were killed; the number wounded was never known. Of the settlers but one was really wounded, though several were scorched and bruised in the fight. None were killed. The scattering flight of the Indians made further pursuit uncertain. Supplies being too limited for an extended chase, as none had reached the little army from those who had returned, and time would be lost in waiting, it was decided to go back to the settlements before taking further active measures. The return was accomplished without interruption.”

Their safe arrival home again was the spontaneous signal for a general jubilee, intensified by the cheering intelligence of the complete victory won over the savages; and augmented, on the following day, by the welcome tidings that the Governor’s authority had arrived to organize and equip a volunteer force against the enemy.

Next: Chapter 3 • Index • Previous: Chapter 1

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/02.html