| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > First Winter Visitor >

Next: Chapter 10 • Index • Previous: Chapter 8

|

The blood more stirs

To rouse a lion than to start a hare.

—Shakespear’s

Henry IV, Part I., Act I.

|

|

I argue not

Against Heaven’s hand or will, nor bate a jot Of heart or hope; but I still bear up and steer Right onward.

—Milton’s

Sonnet.

|

|

God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb.

—Sterne’s

Sentimental Journey.

|

That inestimable of earthly blessings called “health,” having given unerrable premonitions of early departure, from more than one member of our little home circle, the family physician was duly consulted, who gave emphatic enunciation to the opinion that unless we left the city at an early day, we should soon do so from the world; we concluded the former journey—being the shortest, best known, and upon the whole pleasantest to take, for the present—would be the most desirable. This point satisfactorily determined, without a single “if “or “but,” the question naturally presented itself, “Where can we go?” Resolving ourselves into a “Committee of Consultation,” the “pros” and “cons” of different localities were considered, when its feminine members unequivocally expressed their decided preferences for Yo Semite. Now, is it not a reasonable question to ask any man “not set in his ways,” if there would be more than one course left him, under the circumstances, and that one “immediate and unconditonal surrender"—especially when in perfect concert with his own predilections and convictions? So, Yo Semite was chosen. Another and equally pertinent inquiry now interposed, “What can we do after our arrival there?” We could not support physical life on scenery, sublimely beautiful as it unquestionably was! What then? It was true we had some means, but to live upon and absorb them, in comparative indolence, or unproductive personal occupation, was as repellent to every ennobling intuition as it was adverse to provident business foresight. This momentous conundrum, therefore, was propounded to the ladies, and was instantly met with another, “Why cannot we keep hotel?” Why, indeed! There was at least one condition in our favor, not knowing any thing about such a business we possessed the usual qualifications for conducting it. This was something! Learn it? Certainly. Of course we could; but what were the much-tried public to do in the unpleasant interim? Yes, it is very easy to answer, “Do as we would do, and as they have always done. Try your best; take the best that you can find; and make the best of what you get.” But good meals, well cooked, and pleasantly served, with clean-bed accompaniments, are always preferred by the public to either philosophy or argument.

All objections being gracefully overruled, it was decided that in the early spring we should move all our earthly goods, ourselves, and household gods, to Yo Semite, and there enter into the mysterious and unthankful calling of “hotel keepers.” Accordingly, our books, chinaware, and other dispensable articles, were carefully packed, at leisurable intervals, so as to anticipate possible hurry at the start. The sky of our future was not only filled with beatified castles, but was brilliant with the prismatic colors of Hope; and, although

“Hope, like the gleaming taper’s light,

Adorns and cheers our way;

And still, as darker grows the night,

Emits a brighter ray.”

At this particular season of day-dreaming expectancy

Brought by that ill-omened and unprincipled old storm-fiend known as Dame Rumor, who asseverated, with untold assurance, that “no one could ever make a permanent winter home in Yo Semite, inasmuch as snow from the surrounding mountains drifted into it, as into a deep railroad-cut, and filled it half full,” and as its granite walls were from three thousand three hundred to six thousand feet in height, the half of that amount, in snow banks, under the most liberal provision—even including a generous supply for fashionable drinks—might well be deemed excessive for the ordinary purpose of residence there in winter, notwithstanding its admitted value, in reasonable quantities, for snow-shoe evolutions. There could be no doubt of the tenability of these deductions from such premises. No one could be found who had ever been there in winter, therefore no one could be appealed to for the affirmation or contradiction of these stories from Madam Rumor. Therefore before accepting the responsibility of removing the family to such a spot, proof must be positive this way or the other. But one path seemed open for making it so, and duty impelled me to take it, and it was this,—

On the afternoon of the first day of January, 1862, therefore, although vast banks of clouds had, for several days, been drifting up from the south and indicated an approaching rain, the home valedictory was spoken, and departure made by steamboat for Stockton. There were no railroads here in those days. On the following morning, January 2, a seat was secured upon the out-going stage, to a ranch some few miles out, where my horse was kept, and whence I soon started on my mystery-resolving expedition.

| |

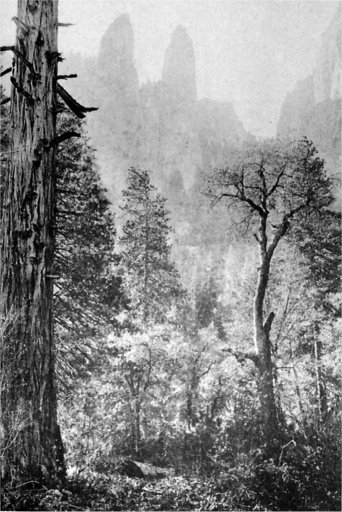

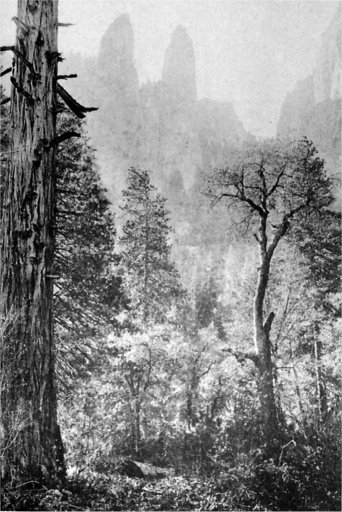

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| Cathedral Spires—Poo-see-na Chuck-ka. | |

| Lowest Spire, 2,579 Feet; Highest Spire, 2678 Feet above Valley. | |

| (See page 409.) | |

Before many miles had been traversed, the threatened rain began to fall, heavily, and to compel a shelter in the nearest way side house. This was continued for the whole of that day, and the next, and the two days following. A few hours’ suspension of hostilities on the fifth day enabled me to again renew the journey. But this time, however, all the shallow hollows across the road had been converted into deep streams, and the ravines into rushing torrents. The difficulty, if not danger of fording these swollen

|

| NOW FOR ANOTHER START. |

Nor was this other than the beginning of the end, inasmuch as the inundating rain kept pouring down for five successive additional days; and news arrived of the sweeping away of bridges and ferry-boats; the tearing up of roads, and the discontinuation of stage and mail communication; the floating off of houses, and the general flooding of the valleys. By natural reasoning, therefore, the inquiry enforced consideration, “If these are the doings of the storm within the boundaries of civilized settlements, what must they not have been beyond their confines in the mountains?” Ought a reluctance to acknowledge defeat be allowed to resist the teachings of common prudence? Who could accomplish impossibilities? Why not return, and await a brightening prospect, for its accomplishment?

“When valor preys on reason,

It eats the sword it fights with.”

These considerations admonished postponement and regression. But how accomplish the latter, with all the ordinary avenues of return closed up? Conferences with other storm-bound travelers provided a way. We would accomplish it by water. There could be no question about this method from quantitative reasons. Four of us, therefore, united our energies and resources, and dispatched one of our number to Merced Falls, on the Merced River, to have a suitable boat constructed for

Hearing of this, Mr. McKean Buchanan, well known to histrionic fame in those days, who had, with his troupe, been performing at “Snellings,” upon the eve of this unusual effluence, and been confined there ever since, desired to join us in our novel method of exit. This was cheerily conceded, and the uncertain cruise commenced. Nearly every man, woman, and child residing near Snellings was present at our departure.

At this time the river upon which we were to venture had largely overflowed its banks, was over a quarter of a mile in width, and its waters had become a rushing, foaming torrent. But out upon its angry bosom we pushed our little craft, and were instantly hurried down it at the rate of about fifteen miles an hour. Just before dusk, an immense gathering of drift had given a sudden sweep to the surging stream, and forced us to a choice between two alternatives—either to jeopard the capsizing of our boat upon the drift, or risk its being swamped by shooting through a narrow opening in it, with an abrupt descent of nearly three feet, through which the water was precipitately plunging. We chose the latter, our steersman shouting, “Pull hard on the oars—pull with all your might;” and, fortunately, the passage was safely accomplished without shipping a quart.

Not so, with our fellow-voyagers, however, who, fearing to follow us, had chosen the alternative we had declined, and their boat was overturned upon the drift. This happening far from the shore, and among numerous cross-currents, with darkness closing in, made deliverance impossible before morning. Here, then, they had to remain through the long night, in their wet clothing, without creature comforts, encompassed by surging rapids that might at any moment tear away their insecure foothold, and without knowledge of probable extrication, their boat having floated away.

As illustrative of the devastation caused by the present storm, it should here be mentioned, that on the very spot where we had moored our wherry, there formerly stood a handsome dwelling, surrounded by fertile gardens, and fruitful orchards; but now, the very soil, upon which they were so recently standing had been washed away, leaving a sad scene of sorrow-stirring desolation on every hand. The house furniture had been hastily removed, only in time to prevent its floating off with the house, and now lay scattered high upon the river’s bank, exposed to the elements.

Our breakfast fire was kindled long before day-dawn, so as to be in readiness to render assistance at the earliest possible moment; and as its first gleams shot up into the darkness, cries for help that had died away with the fire on the previous night, were again most eagerly renewed. To us those cries were rejoicing music, as they assured us of the continued safety of those to whom we hoped soon to bear deliverance.

Climbing up the bluff bank that here bounded the river, so that we could overlook the watery waste below, and definitely ascertain the exact position of our imprisoned companions, and the best way of reaching them, we saw in the shadowy distance the forms of five men approaching, followed by troops of hogs! The foremost of the men proved to be the owner of the house and lands, once his possessions here, and who, with his assistants, had come to obtain some wet grain that was stored in the only building left, standing on an island of the river, from which to feed his hogs. When made aware of the circumstances of the case, he kindly tendered us assistance. Selecting two of his most trusty hands, after declining our proffered help, and preferring his own boat to ours, he launched out upon the rushing current, and was soon lost amid underbrush and whirling eddies.

But a few minutes had elapsed before there arose new cries for help, as this boat also had capsized, when its occupants narrowly escaped drowning. Now there were six to be rescued instead of three. Reinforcements for their succor must be obtained, and immediately. Dispatching two men in each direction, up and down the river, for this purpose, the two remaining prepared the boat for service, and investigated the water-swept country, so as to render efficient assistance when other help arrived. Appeal was not in vain; and, by three o’clock, all were at last delivered from their perilous position.

As Buchanan’s boat had been found upon a drift, we proposed to share our provisions and continue the voyage. To this, however, he would not listen. “No,” said he, “I will return to my wife at Snellings. I would not, for the world, have any other lips than my own tell her the story of this great misfortune. Her nerves are so utterly unstrung by recent experiences that the shock would prove fatal to her. Why, sir, we were in the Snellings Hotel when the flood entirely surrounded us, and it. We felt the building moving, when my wife and daughter, with myself, took the precaution to climb an oak tree that stood by the porch; and just as we had reached it, the entire edifice, with all its contents, floated off, sir! In less than three-quarters of an hour after our deliverance, sir, from the tree, the tree itself was washed away. Then to add this to that sorrow, indiscreetly, would be altogether too much—too much—for her, I assure you, sir.”

But, when returning, another mishap overtook him—he lost his way, and spent this night also a shelterless wanderer! Just before morning he saw an empty wagon, stalled in a muddy cross-road, and lay down in it to rest and sleep, but the cold awoke him as day was breaking, when he discovered this to be his own vehicle!—and only half a mile from town! Mr. Buchanan’s first voyage down the Merced, therefore, would not be cherished as an altogether pleasant memory.

On the following day we continued our boating excursion down the Merced to its confluence with the San Joaquin River, spending the night in the second story of Hill’s Ferry House, the first story being under water. But even here we were compelled to utilize the table tops for both cook-stove and chairs, and only the upper berths could be used for sleeping. A string north wind, blowing squarely in our faces, so much retarded our progress on the San Joaquin (then several miles wide in places) that six days of hard rowing were required to reach the city of Stockton, although only sixty miles distant. Here we gratefully left our boat for use among the streets of that city—then in a flooded condition—and secured passage on the outgoing steamboat for San Francisco; and which, owing to the very high stage of water, shot straight across the overflowed tule lands, instead of following the usual course of the river. Thus ended the first effort to explore the Yo Semite Valley in winter, and proved the aptness of Burns’ sentiment (addressed to a mouse),

“The best-laid schemes o’mice an’ men,

Gang aft a-gley.”

In the ensuing March, as the problem whether or not the great Valley could be safely occupied as a place of residence in winter, remained unsolved; and the same cloud of uncertainty still hovered over our movements, and would so continue to do, unless that theorem was resolved by actual demonstration, another jaunt was accordingly planned, and this time via Mariposa. Here two others volunteered to accompany me, as they also were anxious to see the Yo Semite in her winter robes. Three of us, therefore, set out on this pilgrimage. Colonel Fine, of Mormon Bar, kindly loaned us a donkey to pack our necessary stores to the snow-line, beyond which each man had to be his own pack animal. At Clark’s—now called “Wawona"—we were hospitably entertained by its owner, who was one of our party. Here the unsettled weather detained us for three days. On the fourth we shouldered our loads and set out. A brighter morning never dawned. That evening we camped in about ten inches of snow; but this was soon cleared away; and, around a large camp-fire, many stories were told to beguile away the hours.

Early on the morrow we were again upon our course—the trail being covered up. About nine o’clock, snow had deepened to the knees, and every step was one requiring effort. A fatiguing climb of one snow-covered mountain spur but revealed another, and, still beyond, another; the silvery covering increasing in depth as we advanced. At length one of our companions dropped his pack, and himself upon it, at the same instant, exclaiming, “I’ll be danged [he never swore] if I go any further. I know we can never get through. Besides, this is too much like work for me [but few more industrious men ever lived]. I propose that we all go back, and wait until some of this snow melts off.” To this my other companion gave reluctant concurrence.

At this crisis of affairs another consideration enforced itself upon our attention: How could the winter status of the Valley be ascertained if we waited until spring or summer came? This was intended as a convincing argument to induce a forward movement; but, to make a long story as short as possible, my two companions could not be persuaded to go on, nor the writer to turn back—his mission still unaccomplished. This left but one alternative—

The increasing depth of snow, the solitude of its forest wastes, the absence of all traces of a trail, utter helplessness in case of accident, its unavoidable fatigue and exposure, danger from wild animals, and possible sickness,—all of these, while meriting due solicitude, ought not to deter or hinder him from treading the path of duty. Certainly no man, worthy of so honored an appellation, would for a moment hesitate at such a crisis, where the safety of an entire family depended upon his present movements. No. He must do the best that became his manhood, and leave its results to the one higher Power. While he could not blame the others, who were without the pale of such responsibilities, for returning, he must press on to the goal desired.

Packs were therefore readjusted; about fifteen days’ rations secured; blankets, overcoat, ax, and other sundries tied snugly up; and, after a cheery good-bye to my companions, I started out-alone. There is still a pleasant memory treasured of their kindly and long-lingering farewell look, when passing out of sight—and, as they thought, forever. For several hours after departure from my companions, a feeling of extreme loneliness and isolation crept over me, so that the sight and voice of a chattering tree-squirrel was a real relief; but this soon passed away. The most trying test of endurance was from the constantly breaking crust of frozen snow, that grew deeper at almost every step, and dropped me suddenly down among bushes from which I had again to climb with fatiguing effort, while realizing the uncertain tenure of my foothold after the surface had been gained; thus demoralizing one’s clothing and incising his flesh, while taxing both strength and patience to get out again.

In this manner six wearying days were passed, not walking merely in or over snow, but wallowing through it, and only aver aging about one mile of actual distance per day. At night I slept where any friendly rock or tree offered its reviving shelter. Just as darkness was about to lower down its sable curtain, there being no place of rest or refuge visible in all that snowy waste, and excessive fatigue had seemingly made further progress impossible, I dropped my pack (now grown very heavy) and sat upon it, to write a few loving words to the dear ones at home—possibly the last—before the fast deepening twilight, and in creasing chilliness, had forever banished the opportunity; thinking, also, that when the melting snows of spring had fed the rills, some kindly feet would perhaps wander in search of or for whatever remained of the lonely traveler, and thus find the memoranda. The entry finished, upon looking up I saw that the clouds which had previously draped the forest and the mountain, so that the limit of vision was only a few yards off, had lifted and drifted among the tree-tops, so that from my resting place I could look down some three thousand feet upon the river, where to my ineffable joy I could see green grasses growing, and flowers blooming—and no more snow! It was

Tired? Oh! dear no! Before this strength-giving sight, it seemed utterly impossible to advance another quarter of a mile, even to save one’s life. But, now, the pack was again shouldered, and, “like a giant refreshed with wine,” long and rapid strides were made down the mountain ridge, to the promised land, which was reached about an hour after dark. Out of the snow, the muscle testing, patience-trying snow! I thanked God with a grateful heart. I have often thought since, that the most gifted of singers could never make the song of “The Beautiful, Beautiful Snow” attractive to me. Even when sweetly sleeping that night, beneath the protecting arms of an out-spreading live-oak tree I forgot all my troubles, but one—the snow, the snow, the unfeeling, the never-yielding, the ever-bullying snow. For months afterwards, in my dreams, it was a ghost-shadow, in white—a ghost that would not be “laid"—and was always present.

Awaking on the morrow my gladdened eyes at first looked, doubtingly, on these new surroundings; but, when thoroughly satisfied they were not the creations of an exuberant fancy, a spring of unalloyed, full-hearted, grateful joy began to well up within me, and one that has ever since kept flowing, whenever memory has brought those circumstances back again into review.

The frowning face of a lofty bluff, not far above my encampment, became suggestive of possible trouble in ascending the river, without crossing to the opposite side. This must be ascertained. Taking precautionary measures for insuring the safety of my limited supply of provisions, by tying them to the limb of a tree and allowing it to revert upwards, with ax in hand I started. Fears were soon verified by facts. There were but two alternatives left me: the northern bank of the foaming and angry river must be reached, or the snowy wastes above again sought. I had surely seen enough of the latter, and would therefore choose the former. A tall tree was selected for felling, and the ax applied; but such was the exacting tax upon physical strength for the last six days, that but a very small chip was returned for each stroke. Still, it was a chip; and, if I did not succumb to discouragement, every blow must ultimately tell, and compel the tree to fall, and form a bridge for my deliverance. About noon exhaustion compelled a short respite from labor, the soothing and renewing influences of refreshing sleep, and the replenishment of the inner man. On my way to my supplies, to my astonishment and momentary discomfiture, in the distance I saw a large animal of some kind, and that, too, beneath the very tree in which my limited stock of provisions was stored. A nearer approach disclosed the unwelcome presence of

Candid confession must be made that this discovery was not a little startling at first, especially as my only weapons were an ax, and two limber limbs with which to run away, had I been in condition. What should I do? What could I do, but stand in safety behind a rock, and watch his movements? My usual self-possession soon returning, this could have been done with considerable interest and amusement, but for an anxious consideration for the safety of my supplies, to me invaluable under present circumstances. Bruin’s grotesque and ludicrous antics, in his efforts to clutch them, for the moment absorbed all sense of danger, to either myself or my food, by their diverting clumsiness.

Now he would sit upon his haunches, apparently ruminating upon some plan that should successfully put him in possession of that which his keen sense of hunger scented from afar. Then he would rise upon his feet, and, by a side lunge, attempt to catch hold of a bough with his fore paw; simultaneously throwing the weight of his huge body upon the opposite hind foot, as though by this he hoped to stretch himself to the required length, to secure the much-coveted prize—but missed it every time. Unlike a passenger once seated at the dinner-table of a Mississippi steamboat, who, being curtly and surlily asked, by his fellow-passenger, “Can you reach that butter?” immediately stretched out his arm, as though about to comply, when he withdrew it, without passing the article in question, and answered, stutteringly, “Ye-ye-yes, I c-c-can j-j-just r-r-reach it!” There was this difference, then, between the gentleman and the butter, and the grizzly with the pack-one could reach it, and the other could not.

Finding his efforts still unrewarded, and the smell alone possibly being altogether too unsatisfying, he began to cast wistful glances at the trunk of the tree, and along its branches, as though cogitating upon the possibility of securing the coveted treasure by climbing the tree. Doubt evidently had changed to hope, for, dropping to his feet, he ran with a bound to the tree, and began to scramble up it. But, either his body was too heavy for its strength, or, there was an uncommendable lack of will-power—an occasional experience in similar forms of the genus homo—inasmuch as less than half of the height had been overcome, when he began to hesitate, then to back down. Fearing, however, that the pangs of hunger might provide bruin with sufficient intelligence to encompass their capture, and my dismay, I struck a rattling blow upon a large hollow log, accompanied with a loud shout; when, looking around towards the spot whence the noise proceeded, he started upon an ambling run in the opposite direction, and was soon lost in the distance. It may not be necessary here to aver that not a single arrow of sorrow pierced my hea rt at his abrupt departure.

After rest and refreshment, the attack was renewed upon the tree; and, about three o’clock that afternoon, it began to give premonitions of a downfall. As Mungo Park once said, when suffering with thirst upon the deserts of Africa, and heard the croaking of frogs, knowing that the sound was indicative of water being near, with gladness exclaimed, “It was heavenly music to my ears;” so was the cracking of that tree to me. Luckily it fell just right, and reached the other side. Creeping across it—I was too weak to walk it—I discovered signs of a dim and almost unused trail, passing up the northern bank of the river. This augured successful progress in the right direction.

Returning to camp, a fresh supply of bread was made up, and baked upon hot rocks in front of the fire, or upon dried sticks; and on the following day my journey was renewed. For three days I threaded my way among bowlders, creeping under or over, or lowering myself between them, or worked it through underbrush; but as there was no snow to encounter, and the close of each day showed encouraging progress, every indication was in favor of a hopeful finale. On the night of the third day in the river cañon, and the tenth of my lonely pilgrimage, I successfully gained the object of my earnest yearnings, and undiscouraged efforts. I had reached the Valley, and, with sympathetic Cowper, felt:—

“0 scenes surpassing fable, and yet true

Scenes of accomplished bliss; which who can see,

Though but in distant prospect, and not feel

His soul refresh’d with foretaste of the joy.”

Especially after such experiences. Once here, and out of the unknown region wherein I had been a wanderer, every water-fall and mountain peak were dearly “familiar to me as household words.” My heart seemed to leap with very joy. In spirit I metaphorically embraced them as well-known friends. Believe me, there was real felicity enjoyed at such a moment, for I was truly happy. And

“When the shore is won at last,

Who will count the billows past?”

A grateful addition to my gladness of heart at reaching the desired goal was the discovery that snow did not interpose any insuperable obstacles to a safe residence in the grand old valley during winter—and that Dame Rumor, as usual, was in error. It is true there were numerous patches of snow, several feet in depth, hidden away in shady places; but nearly the entire surface of the valley was found to be free from it. This, the sole object of my eventful journey, being demonstrated beyond peradventure, after a brief rest, I left the valley on the eleventh day, and, about noon of the day following, arrived at a little quartz-mill, far down in the cañon of the Merced, where I once more looked upon a human face. I will leave others to guess, for they cannot fully realize, how delightfully welcome was that sight to me. If any one entertains a doubt of this, let him pass eleven days, alone, without it.

Upon the return of my companions to the settlements without me, and the story being told of my having started on through the deep snow, alone, there were gloomy forebodings expressed of my never again being seen, alive. Colonel Fine care fully treasured the note of thanks I had sent him for the use of his donkey, thinking to forward it to my ffiends, as possibly the last souvenir from me! In this they were fortunately disappointed.

Next: Chapter 10 • Index • Previous: Chapter 8

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/09.html