The Gates of the Valley, from Inspiration Point

[showing workers constructing the wagon-road]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Ramblings > August 1-11, 1870>

The Gates of the Valley, from Inspiration Point [showing workers constructing the wagon-road] |

President Hopkins and family go with us. They had stayed at Paragoy’s over Sunday. I think we kept Sunday better. Glorious ride this morning, through the grand fir forests. This is enjoyment, indeed.

The trail is tolerably good until it reaches the edge of the Yosemite chasm. On the trail a little way below this edge there is a jutting point called "Inspiration Point," which gives a good general view of the lower end of the valley, including El Capitan, Cathedral Rock, and a glimpse of Bridal Veil Fall. After taking this view we commenced the descent into the valley.

The trail winds backward and forward on the almost perpendicular sides of the cliff making a descent of about three thousand feet in three miles. It was so steep and rough that we preferred walking most of the way and leading the horses. Poor old Mrs. Hopkins, though a heavy old lady, was afraid to ride, and therefore walked the whole way.

At last, 10 A. M., we were down, and the gate of the valley is before us, El Capitan guarding it on the left, and Cathedral Rock on the right; while over the precipice on the right, the silvery gauze of Bridal Veil is seen swaying to and fro.

We encamped in a fine forest, on the margin of Bridal Veil Meadow, under the shadow of El Capitan, and about one-quarter of a mile from Bridal Veil Fall. Turned our horses loose to graze, cooked our midday meal, refreshed ourselves by swimming in the Merced, and then, 4:30 P. M., started to visit Bridal Veil. We had understood that this was the best time to see it.

Very difficult clambering to the foot of the fall up a steep incline, formed by a pile of huge bowlders fallen from the cliff. The enchanting beauty and exquisite grace of this fall well repaid us for the toil. At the base of the fall there is a beautiful pool.

Standing on the rocks, on the margin of this pool, right opposite the fall, a most perfect unbroken circular rainbow is visible. Sometimes it is a double circular rainbow. The cliff more than six hundred feet high; the wavy, billowy, gauzy veil, reaching from top to bottom; the glorious crown, woven by the sun for this beautiful veiled bride,—those who read must put these together and form a picture for themselves, by the plastic power of the imagination.

Some of the young men took a swim in the pool and a shower-bath under the fall. I would have joined them, but I had just come out of the Merced River. After enjoying this exquisite fall until after sunset, we returned to camp. On our way back, amongst the loose rocks on the stream margin, we found and killed another rattlesnake. This is the fourth we have killed.

Hawkins, the enterprising and indefatigable, has been, to-day, up to the hotel for supplies. He has returned, bringing among other things, a quarter of mutton, and two pounds of butter. These, with a due amount of bread, etc., scarcely stayed our fierce appetites.

After supper we lit cigarettes, gathered around the camp-fire and conversed. Some question of the relative merits of novelists was started, and my opinion asked. By repeated questions I was led into quite a disquisition on art and literature, which lasted until bedtime. Before retiring, as usual we piled huge logs on the camp-fire; then rolled ourselves in our blankets, within reach of its warmth.

Forming part of the cliff at the base of Bridal Veil Fall, I observed a remarkable mass of dark rock, like diorite, veined in the most complicated manner with whitish granite. In some places the granite predominates, and incloses isolated masses of diorite.

Bridal Veil Fall |

Started this morning up the valley. As we go, the striking features of Yosemite pass in procession before us. On the left, El Capitan, Three Brothers, Yosemite Falls; on the right, Cathedral Rock, Cathedral Spires, Sentinel Rock.

Cathedral Spires really strongly remind one of a huge cathedral, with two tall, equal spires, five hundred feet high, and several smaller ones. I was reminded of old Trinity, in Columbia. But this was not made with hands, and is over two thousand feet high.

Stopped at Hutchings’ and took lunch. Here I received letters from home. All well, thank God! Here again met President Hopkins and party; also our friend Miss Bloomer greeted us merrily. Soulé seems deeply smitten, poor fellow! We here had our party photographed in costume. The photographer is none of the best, but we hope the picture will be a pleasure to our friends in Oakland.

We first tried it on horseback, but found it impossible. We must be content to leave out these noble animals. Captain is secretly glad—he has left his high-stepping gray at Clark’s, and now bestrides a sorry mule. Those ears, he thinks, don’t look martial. Now, then, for a striking group!

As the most venerable of the party, my position was in the middle, and my bald head, glistening in the sunshine, was supposed to give dignity to the group. I was supported on either hand by Captain and Perkins, as the handsomest. Dignity supported by beauty—fitting union!

Beyond these, on one side stood grave Bolton, in stiff attitude, with his hand resting on Hawkins’ gun; while on the other, Linderman, with broad-brimmed hat thrown back, and chest thrown forward, and his gun strapped across his back, tried in vain to make his humorous face look fierce. On the extreme wings, Cobb with his inevitable rifle, and Phelps with his loose-jointed legs, struck each a tragic attitude.

In the foreground, at our feet, were placed the other three. Hawkins’ burly bulk, in careless position, occupied the middle, while Pomroy gave solemnity to the left; and on the right, Stone, reclining on his elbow, gathered up his long legs to bring them, if possible, within the view of the great eye of the camera, and placed his broad-brim on his knee, in vain attempts to conceal "their utmost longitude." Far in the background was the granite wall of Yosemite, and the wavy, white waters of the fall. The result is seen in the frontispiece. [The frontispiece of the earlier editions is shown opposite this page.—Editor]

In the afternoon went on up the valley, and again the grand procession commences. On the left, Royal Arches, Washington Column, North Dome; on the right, Sentinel Dome, Glacier Point, Half Dome. We pitched our camp in a magnificent forest, near a grassy meadow (the same Hawkins had selected from Glacier Point yesterday), on the banks of Tenaya Fork, and under the shadow of our venerated preacher and friend, the Half Dome, with also North Dome, Washington Column, and Glacier Point in full view.

After unsaddling and turning loose our horses to graze, and resting a little, we went up the Tenaya Cañon about one and a half miles, to Mirror Lake, and took a swimming bath. The scenery about this lake is truly magnificent.

The cliffs of Yosemite here reach the acme of imposing grandeur. On the south side the broad face of South Dome rises almost from the water, a sheer precipice, near five thousand feet perpendicular; on the north side, North Dome, with its finely rounded head, to an almost equal height. Down the cañon, to the west, the view is blocked by the immense cliffs of Glacier Point and Washington Column; and up the cañon, to the east, the cliffs of the Tenaya Cañon, and Clouds’ Rest, and the peaks of the Sierra in the background.

On returning to camp, as we expected to remain here for several days, we carried with us a number of "shakes" (split boards), and constructed a very good table, around which we placed logs for seats. We cooked our supper, sat around our rude board, and enjoyed our meal immensely. After supper, sat around Our camp-fire, smoked our cigarettes, and sang in chorus until 9:30 P. M., then rolled ourselves, chrysalis-like, in our blanket cocoons, and lay still until morning.

Already I observe two very distinct kinds of structure in the granite of this region, which, singly or combined, determine all the forms about this wonderful valley. These two kinds of structure are the concentric structure, on an almost inconceivably grand scale; and a rude, columnar structure, or perpendicular cleavage, also on a grand scale. The disintegration and exfoliation of the granite masses of the concentric structures give rise to the bald, rounded domes; the structure itself is well seen on Sentinel Dome, and especially in the Royal Arches.

The columnar structure, by disintegration, gives rise to Washington Column, and the sharp peaks, like Sentinel Rock and Cathedral Spires. Both these structures exist in the same granite, though the one or the other may predominate.

In all the rocks about Yosemite there is a tendency to cleave perpendicularly. In addition to this, in many there is also a tendency to cleave in concentric layers, giving rise to dome-like forms. Both are well seen combined in the grand mass of Half Dome. The perpendicular face-wall of this dome is the result of the perpendicular cleavage. Whatever may be our theory of the formation of Yosemite chasm and the perpendicularity of its cliffs, we must not leave out of view this tendency to perpendicular cleavage. I observe, too, that the granite here is very coarse-grained, and disintegrates into dust with great rapidity.

I observed, to-day, the curious straw-and grass-covered stacks in which the Indians store and preserve their supplies of acorns.

AUGUST 3

This has been to me a day of intense enjoyment. Started off this morning. with six others of the party, to visit Vernal and Nevada Falls. There are many Indians in the valley. We do not think it safe to leave our camp. [We learned afterwards that we might have left the camp unguarded with perfect safety.] We therefore divide our party every day, a portion keeping guard. Soulé, Phelps, and Perkins were camp-guard to-day.

The Vernal and Nevada Falls are formed by the Merced River itself; the volume of water, therefore, is very considerable in all seasons. The surrounding scenery, too, is far finer, I think, than that of any other fall in the valley.

The trail is steep and very rough, ascending nearly two thousand feet to the foot of Nevada Fall. To the foot of Vernal Fall, the trail passes through dense woods, close along the banks of the Merced, which here rushes down its steep channel, forming a series of rapids and cascades of enchanting beauty.

We continued our way on horseback, until it seemed almost impossible for horses to go any farther; we then dismounted, unsaddled and hitched our horses, and proceeded on foot. We afterwards discovered that we had already gone over the worst part of the trail to the foot of Vernal Fall before we hitched; we should have continued on horseback to the refreshment cabin at the foot of Vernal Fall.

We arrived at the refreshment cabin very much heated, and took some refreshment before proceeding. Here we again saw the bright face, the laughing eyes, and fat legs of Miss Bloomer, which were also a very great refreshment. Alas for Captain! he is not with us to-day.

The Vernal Fall is an absolutely perpendicular fall of four hundred feet, surrounded by the most glorious scenery imaginable. The exquisite greenness of the trees, the grass, and the moss renders the name peculiarly appropriate. The top of the fall is reached by. step-ladder, which ascends the absolutely perpendicular face of the precipice. From the top the view is far grander than from below; for we take in the fall and the surrounding scenery at one view.

An immense natural parapet of rock rises, breast-high, above the general surface of the cliff near the fall. Here one can stand securely, leaning on the parapet, and enjoy the magnificent view.

The river pitches, at our very feet, over a precipice four hundred feet high, into a narrow gorge, bounded on either side by cliffs such as are seen nowhere except in Yosemite, and completely blocked in front by the massive cliffs of Glacier Point, three thousand two hundred feet high; so that it actually seems to pitch into an amphitheater, with rocky walls higher than its diameter.

Oh! the glory of the view!—the emerald green and snowy white of the falling water; the dizzying leap into the yawning chasm; the roar and foam and spray of the deadly struggle with rocks below; the deep green of the somber pines, and the exquisitely fresh and lively green of grass, ferns, and moss, wet with eternal spray; the perpendicular rocky walls, rising far above us toward the blue arching sky. As I stood there, gazing down into the dark and roaring chasm, and up into the clear sky, my heart swelled with gratitude to the Great Author of all beauty and grandeur.

After enjoying this view until we could spare no more time, we went on about one-half mile to the foot of Nevada Fall. Mr. Pomroy and myself mistook the trail, and went up the left side of the river to the foot of the fall. To attain this point we had to cross two roaring cataracts, under circumstances of considerable danger, at least to any but those who possess steady nerves. We finally succeeded in clambering to the top of a huge bowlder, twenty feet high, immediately in front of the walls, and only thirty or forty feet from it. Here, stunned by the roar, and blinded by the spray, we felt the full power and grandeur of the fall.

From this place we saw, and greeted with Indian yell, our companions on the other side of the river. After remaining here an hour, we went a little down the stream and crossed to the other side, and again approached the fall. The view from this, the right side, is the one usually taken. It is certainly the finest scenic view, but the power of falling water is felt more grandly from the nearer view on the other side. The lover of intense ecstatic emotion will prefer the latter; the lover of quiet scenic beauty will prefer the former. The poet will seek inspiration in the one, and the painter in the other.

The Nevada Fall is, I think, the grandest I have ever seen. The fall is six hundred to seven hundred feet high. It is not an absolutely perpendicular leap, like Vernal, but is all the grander on that account; as, by striking several ledges in its downward course, it is beaten into a volume of snowy spray, ever-changing in form, and impossible to describe. From the same cause, too, it has a slight, S-like curve, which is exquisitely graceful.

But the magnificence of the Yosemite cascades, especially of Vernal and Nevada Falls, is due principally to the accompanying scenery. See Cap of Liberty and its fellow peak, rising perpendicular, tall and sharp, until actually (I speak without exaggeration) the intense blue sky and masses of white clouds seem to rest supported on their summits. The actual height above the fall is, I believe, about two thousand feet.

About 3 P. M. started on our return. There is a beautiful pool, about three hundred feet long and one hundred and fifty to two hundred feet wide, immediately above the Vernal Fall. Into this pool the Merced River rushes as a foaming rapid, and leaves it only to precipitate itself over the precipice, as the Vernal Fall. The fury with which the river rushes down a steep incline, into the pool, creates waves like the sea. On returning, all of us who were good swimmers refreshed ourselves by swimming in this pool.

I enjoyed the bath immensely; swam across, played among the waves, contended with the swift current, shouted and laughed like the veriest boy of them all. The water was of course very cold, but we have become accustomed to this. On coming out of my bath, I took one final look over the rocky parapet, over the fall, and into the yawing chasm below.

Returned to camp 5 P. M., fresh and vigorous, and with a keen appetite for supper. After enjoying that most important meal, as usual, we gathered around our camp-fire, sat on the ground, and the young men sang in chorus.

Day-dawn in Yosemite—The Merced River |

AUGUST 4

This has been to me an uneventful day; I stayed in camp to-day as one of the camp-guard, while the camp-guard of yesterday visited the Vernal and Nevada Falls.

I have lolled about camp, writing letters home, sewing on buttons, etc.; but most of the time in a sort of day-dream—a glorious day-dream in the presence of this grand nature. Ah! this free life in the presence of great Nature, is indeed delightful.

There is but one thing greater in this world; one thing after which, even under the shadow of this grand wall of rock, upon whose broad face and summit line projected against the clear blue sky with upturned face I now gaze; one thing after which even now I sigh with inexpressible longing, and that is Home and Love.

A loving human heart is greater and nobler even than the grand scenery of Yosemite. In the midst of the grandest scenes of yesterday, while gazing alone upon the falls and the stupendous surrounding cliffs, my heart filled with gratitude to God and love to the dear ones at home; my eyes involuntarily overflowed, and my hands clasped in silent prayer.

In the afternoon we took our usual swim in the Mirror Lake; after which, of course, supper and bed.

AUGUST 5

To-day to Yosemite Falls. This was the hardest day’s experience yet. We thought we had plenty of time, and therefore started late. Stopped a moment at the foot of the falls, at a saw-mill, to make inquiries. Here found a man in rough miller’s garb, whose intelligent face and earnest, clear blue eye, excited my interest. After some conversation, discovered that it was Mr. Muir, a gentlemen of whom I had heard much from Mrs. Prof Carr and others. He had also received a letter from Mrs. Carr, concerning our party, and was looking for us. We were glad to meet each other. I urged him to go with us to Mono, and he seemed disposed to do so.

We first visited the foot of the lower fall, which is about four hundred feet perpendicular, and after enjoying it for a half hour or more, returned to the mill. It was now nearly noon. Impossible to undertake the difficult ascent to the upper fall without lunch; I therefore jumped on the first horse I could find (mine was unsaddled) and rode to Mr. Hutchings’ and took a hearty lunch, to which Mr. Hutchings insisted upon adding a glass of generous California wine. On returning, found the rest of the party at the mill. On learning my good fortune, they also went and took lunch.

We now commenced the ascent. We first clambered up a mere pile of loose débris (talus), four hundred feet high, and inclined at least 45° to 50°. We had to keep near to one another, for the bowlders were constantly loosened by the foot, and went bounding down the incline until they reached the bottom. Heated and panting, we reached the top of the lower fall, drank, and plunged our heads in the foaming water until thoroughly refreshed. After remaining here nearly an hour, we commenced the ascent to the foot of the upper fall.

Here the clambering was the most difficult and precarious I have ever tried; sometimes climbing up perpendicular rock faces, taking advantage of cracks and clinging bushes; sometimes along joint-cracks, on the dizzy edge of fearful precipices; sometimes over rock faces so smooth and highly inclined that we were obliged to go on hands and knees. In many places a false step would be fatal. There was no trail at all; only piles of stones here and there, to mark the best route.

But when at last we arrived, we were amply repaid for our labor. Imagine a sheer cliff, sixteen hundred feet high, and a stream pouring over it. Actually, the water seems to fall out of the very sky itself As I gaze upwards now, there are wisps of snowy cloud just on the verge of the precipice above; the white spray of the dashing cataract hangs, also, apparently almost motionless on the same verge. It is difficult to distinguish wisps of spray from wisps of cloud. So long a column of water and spray is swayed from side to side by the wind; and, also, as in all falls, the resistance of the rocks at the top, and of the air in the whole descent, produces a billowy motion.

The combination of these two motions, both so conspicuous in this fall, is inexpressibly graceful. When the column swayed far to the left, we ran by on the right, and got behind the fall, and stood gazing through the gauzy veil, upon the cliffs on the opposite side of the valley. At this season of the year the Yosemite Creek is much diminished in volume. It strikes slightly upon the face of the cliff about midway up. In the spring and autumn, when the river is full, the fall must be grand indeed. It is then a clear leap of sixteen hundred feet, and the pool which it has hollowed out for itself in the solid granite, is plainly visible twenty to thirty feet in advance of the place on which it now falls.

We met here, at the foot of the fall, a real typical specimen of a live Yankee. He has, he says, a panorama of Yosemite, which he expects to exhibit in the Eastern cities. It is evident that he is "doing" Yosemite only for the purpose of getting materials of lectures to accompany his exhibitions.

Coming down, in the afternoon, the fatigue was less, but the danger much greater. We were often compelled to slide down the face of rocks in a sitting posture, to the great detriment of the posterior portion of our trowsers. Reached bottom at half-past five P. M. Here learned from Mr. Muir that he would certainly go to Mono with us. We were much delighted to hear this. Mr. Muir is a gentleman of rare intelligence, of much knowledge of science, particularly of botany, which he has made a specialty. He has lived several years in the valley, and is thoroughly acquainted with the mountains in the vicinity. A man of so much intelligence tending a saw mill!—not for himself but for Mr. Hutchings. This is California!

After arranging our time of departure from Yosemite with Mr. Muir, we rode back to camp. I enjoyed greatly the ride to camp, in the cool of the evening. The evening view of the valley was very fine, and changing at every step. Just before reaching our camp, there is a partial distant view of the Illilouette Fall—the only one I know of in the valley. Many of the party seem wearied this evening. For myself, I feel fresh and bright. We were all, however, sound asleep by 8 P. M. [Our party did not visit the Illilouette Fall, but on a subsequent trip to Yosemite I did so. The following is a brief description, taken from my journal, which I introduce here in order to complete my account of the falls of this wondrous valley.]

AUGUST 15, 1872

started with Mr. Muir and my nephew Julian, to visit Illilouette Falls. Hearing that there was no trail, and that the climb is more difficult even than that to the Upper Yosemite, the rest of the party backed out. We rode up the Merced, on the Vernal Fall trail, to the junction of the Illilouette Fork. Here we secured our horses and proceeded on foot up the cañon. The rise, from this to the foot of the falls, is twelve hundred to fifteen hundred feet.

The whole cañon is literally filled with huge rock fragments—often hundreds of tons in weight—brought down from the cliffs at the fall. The scramble up the steep ascent over these bowlders was extremely difficult and fatiguing. Oftentimes the creek bed was utterly impracticable, and we had to climb high up the sides of the gorge and down again. But we were gloriously repaid for our labor.

There are beauties about this fall which are peculiar, and simply incomparable. It was to me a new experience, and a peculiar joy. The volume of water, when I saw it, was several times greater than either Yosemite or Bridal Veil. The stream plunges into a narrow chasm, bounded on three sides by perpendicular walls nearly one thousand feet high. The height of the fall is six hundred feet.

Like Nevada, the fall is not absolutely perpendicular. but strikes about half-way down on the face of the cliff. But instead of striking on projecting ledges and being thus beaten into a great volume of foam, as in the latter, it glides over the somewhat even surface of the rock, and is woven into the most exquisite lacework, with edging fringe and pendent tassels, ever-changing and ever-delighting.

It is simply impossible even to conceive, much less to describe, the exquisite delicacy and tantalizing beauty of the ever-changing forms. The effect produced is not tumultuous excitement, or ecstasy, like Nevada, but simple, pure, almost childish delight. Now as I sit on a great bowlder, twenty feet high, right in front of the fall, see! the midday sun shoots its beams through the myriad water-drops which leap from the top of the cascade as it strikes the edge of the cliff. As I gaze upwards, the glittering drops seem to pause a moment high in the air and then descend like a glorious star-shower.

North Dome — South (Half) Dome [with Linderman, Cobb, and Bolton mounted] |

Slept late this morning. Some of the party stiff and sore; I am all right. The camp-guard of yesterday visited Yosemite Falls to-day, and we stayed in camp. Visited Mirror Lake this morning to see the fine reflection of the surrounding cliffs in its unruffled waters, in the early morning. Took a swim in the lake; spent the rest of the morning washing clothes, writing letters, and picking and eating raspberries in Lamon’s Garden.

To a spectator the clothes-washing forms a very interesting scene. To see us all sitting down on the rocks, on the banks of the beautiful Tenaya River, scrubbing, and wringing, and hanging out! It reminds one of the exquisite washing scene of Princess Nausicaa and her damsels, or of Pharoah’s daughter and her maids.

Change the sex, and where is the inferiority in romantic interest in our case? Ah the sex! yes, this makes all the difference between the ideal and common—between poetry and prose. If it were only seven beautiful women, in simple attire, and I, like Ulysses, a spectator just waked from sleep by their merry peals of laughter! But seven rough, bearded fellows! think of it! We looked about us, but found no little Moses in the bullrushes. So we must e’en take Mr. Muir and Hawkins to lead us through the wilderness of the High Sierra.

In the afternoon we moved camp to our previous camping-ground at Bridal Veil meadow. We were really sorry to break up our camp on Tenaya Creek. We have had delightful times here. We called it University Camp. Soon after leaving camp, Soulé and myself riding together, heard a hollow rumbling, then a crashing sound. "Is it thunder or earthquake?" Looking up quickly, the white streak down the cliff of Glacier Point, and the dust there rising from the valley, revealed the fact that it was the falling of a huge rock mass from Glacier Point.

We rode down in the cool of the evening, and by moonlight. Took leave of our friends in the valley-McKee and his party, Mr. and Mrs. Hutchings, Mrs. Yelverton, Miss Bloomer (whom we again met, and with whom Captain exchanged photographs); sad leave of our friends, now dear friends, of the valley; the venerable and grand Old South Dome under whose shadow we had camped so long; North Dome, Washington Column, Royal Arches, Glacier Point; then Yosemite Falls, Sentinel Rock, Three Brothers.

By this time night had closed in, but the moon was near full, and the shadows of Cathedral Spires and Cathedral Rock lay across our path, while the grand rock mass of El Capitan shone gloriously white in the moonlight. The ride was really enchanting to all, but affected us differently. The young men rode ahead, singing in chorus. I lagged behind, and enjoyed it in silence. The choral music, mellowed by distance, seemed to harmonize with the scene, and to enhance its holy stillness.

About hall-past eight P. M. we encamped on the western side of Bridal Veil meadow. After supper we were in fine spirits, contended with each other in gymnastic exercises, etc. Then gathered hay, made a delightful, fragrant bed, and slept dreamlessly.

At Mr. Hutchings’ I again received letters from home—very happy to know that they are all well.

AUGUST 7

SUNDAY.—Got up late—6 A. M.—as is common everywhere on this day of rest. Now, about to leave for Mono, Captain must have his horse or he cannot accompany us. He only hired the mule while in Yosemite. Mr. Perkins volunteered to ride the mule back to Clark’s and bring Captain’s horse. He started very early this morning, and hopes to be back by bedtime.

About 11 A. M. took a quiet swim in the river; for we think a clean skin is next in importance to a pure heart. During the rest of the morning I sat and enjoyed the fine view of the opening or gate of the valley, from the lower side of the meadow. There stands the grand old El Capitan in massive majesty on the left, and Cathedral Rock and the Veiled Bride on the right. I spent the morning with this scene before me.

While sitting here I again took out my little sewing-case and darned my trowsers, a little broken by my experiments in sliding. day before yesterday. God bless the dear thoughtful one who provided me with this necessary article! God bless the little fingers which arranged these needles and wound so neatly the thread! May God’s choicest blessings rest on the dear ones at home! May He, the Infinite Love, keep them in health and happiness until I return! Surely, absence from home is sometimes necessary to make us feel the priceless value of loving hearts.

There is considerable breeze to-day; and now, while I write, the Bride’s veil is wafted from side to side, and sometimes lifted until I can almost see the blushing face of the Bride herself—the beautiful spirit of the falls. But whose bride? Is it old El Capitan? Strength and grandeur united with grace and beauty! Fitting union!

At 3 P. M. went again alone to the lower side of the meadow, and sat down before the gate of the valley. From this point I look directly through the gate and up the valley. There again, rising to the very skies, stands the huge mass of El Capitan on one side, and on the other the towering peak of the Cathedral, with the veiled Bride retiring a little back from the too ardent gaze of admiration; then the cliffs of Yosemite, growing narrower and lower on each side, beyond. Conspicuous, far in the distance, see! old South Dome and Cloud’s Rest.

The sky is perfectly serene, except heavy masses of snow-white cumulus, sharply defined against the deep blue of the sky. filling the space beyond the gate. The wavy motion of the Bride’s veil, as I gaze steadfastly upon it, drowses my sense; I sit in a kind of delicious dream, the scenery unconsciously mingling with my dream.

5 P. M. Went, all of us, this afternoon, to visit the Bride. Saw again the glorious crown set by the sun upon her beautiful head. Swam in the pool at her feet. Tried to get a peep beneath the veil, but got pelted beyond endurance with water-drops, by the little fairies which guard her beauty, for my sacreligious rudeness. Nevertheless, came back much exhilarated, and feeling more like a boy than I had felt for many, many years.

Perkins returned with Captain’s horse, to supper.

8 P. M. After supper, went again alone into the meadow, to enjoy the moonlight view. The moon is long risen, and "near her highest noon," but not yet visible in this deep valley, although I am sitting on the extreme northern side. Cathedral Rock and the snowy veil of the Bride, and the whole right side of the cañon, is in deep shade, and its serried margin strongly relieved against the bright moonlit sky.

On the other side are the cliffs of El Capitan, snow-white in the moonlight. Above all arched the deep black sky, studded with stars gazing quietly downward. Here, under the black arching sky and before the grand cliffs of Yosemite, I lifted my heart in humble worship to the great God of Nature.

AUGUST 8

To-day we leave Yosemite; we therefore get up very early, intending to make an early start. I go out again into the meadow, to take a final farewell view of Yosemite. The sun is just rising; wonderful, warm, transparent golden light, (like Bierstadt’s picture,) on El Capitan; the whole other side of the valley in deep, cool shade; the bald head of South Dome glistening in the distance. The scene is magnificent.

But see! just across the Merced River from our camp, a bare trickling of water from top to bottom of the perpendicular cliff I have not thought it worth while to mention it before; but this is the Fall called the Virgin’s Tears. Poor Virgin! she seems passeé; her cheeks are seamed, and channeled, and wrinkled; she wishes she was a Bride, too, and had a veil: so near El Capitan, too, but he will not look that way. I am sorry I have neglected to sing her praises.

We experienced some delay in getting off this morning. Our horses have feasted so long on this meadow that they seem disinclined to be caught. Pomroy’s ill-favored beast, Old 67, gave us much trouble. He had to be lassoed at last. We forded the river immediately at our camp. Found it so deep and rough, that several of the horses stumbled and fell down. We now took Coulterville trail; up, up, up, backwards and forward, up, up, up the almost perpendicular side of the cañon below the gate.

The trail often runs on a narrow ledge, along the almost perpendicular cliff. A stumble might precipitate both horse and rider one thousand feet, to the bottom of the chasm. But the horses know this as well as we. They are very careful. About the place where Mono trail turns sharp back from Coulterville trail, Mr. Muir overtook us. Without him we would have experienced considerable difficulty, for the trail being now little used, except by shepherds, is very rough, and so blind that it is almost impossible to find it. or having found, to keep it. My horse cast two of his shoes to-day. Yet I had examined them before leaving Yosemite, and found them all right.

Made about fourteen miles, and about 2 P. M. reached a meadow near the top of Three Brothers. Here we camped for the night in a most beautiful grove of fir— Abies concolor and magnifica, chose our sleeping-places; cut branches of spruce and made the most delightful elastic and aromatic beds, and spread our blankets in preparation for night. After dinner, lay down on our blankets, and gazed up through the magnificent tall spruces into the deep blue sky and the gathering masses of white clouds.

Mr. Muir gazes and gazes, and cannot get his fill. He is a most passionate lover of nature. Plants, and flowers, and forests, and sky, and clouds, and mountains, seem actually to haunt his imagination. He seems to revel in the freedom of this life. I think he would pine away in a city or in conventional life of any kind. He is really not only an intelligent man, as I saw at once, but a man of strong, earnest nature, and thoughtful, closely observing and original mind. I have talked much with him to-day about the probable manner in which Yosemite was formed. He fully agrees with me that the peculiar cleavage of the rock is a most important point, which must not be left out of account.

He farther believes that the valley has been wholly formed by causes still in operation in the Sierra—that the Merced Glacier and the Merced River and its branches, when we take into consideration the peculiar cleavage, and also the rapidity with which the fallen and falling bowlders from the cliffs are disintegrated into dust, has done the whole work. The perpendicularity is the result of cleavage; the want of talus is the result of the rapidity of disintegration, and the recency of the disappearance of the glacier. I differ with him only in attributing far more to pre-glacial action. I may, I think, appropriately introduce here my observations on the evidence of glacial action in Yosemite.

It is well known that a glacier once came down the Tenaya Cañon. I will probably see abundant evidences of this high up this cañon, to-morrow and next day. That this glacier extended into the Yosemite has been disputed, but is almost certain. Mr. Muir also tells me that at the top of Nevada Fall there are unmistakable evidences (polishings and scorings) of a glacier. There is no doubt, therefore, that anciently a glacier came down each of these cañons. Did they meet and form a Yosemite glacier? From the projecting rocky point which separates the Tenaya from Nevada Cañon, there is a pile of bowlders and débris running out into the valley, near Lamon’s garden, like a continuation of the point.

Mr. Muir thinks this unmistakably a medial moraine, formed by the union of the Tenaya and Nevada glaciers. I did not examine it carefully. Again, there are two lakes in the lower Tenaya Cañon, viz., Mirror Lake and a smaller lake lower down. Below Mirror Lake, and again below the smaller lake, there is an immense heap of bowlders and rubbish. Are not these piles terminal moraines, and have not the lakes been formed by the consequent damming of the waters of the Tenaya? These lakes are filling up. It seems probable that the meadow, also, on which we camped, has been formed in the same way, by a moraine just below the meadow, marked by a pile of débris there, also.

Whether the succession of meadows in the Yosemite, of which the Bridal Veil meadow is the lowest, have been similarly formed, requires and really deserves further investigation. I strongly incline to the belief that they have been, and that a glacier once filled Yosemite. l observed other evidences, but I must visit this valley again, and examine more carefully.

After discussing these high questions with Mr. Muir for some time, we walked to the edge of the Yosemite chasm, and out on the projecting point of Three Brothers, called Eagle Point. Here we had our last, and certainly one of the most magnificent views of the valley and the High Sierra. I can only name the points which are in view, and leave the reader to fill out the picture. As we look up the valley, to the near left is the Yosemite Falls, but not a very good view; then Washington Column, North Dome; then grand old South Dome.

The view of this grand feature of Yosemite is here magnificent. It is seen in half profile. Its rounded head, its perpendicular rock face, its towering height, and its massive proportions are well seen. As the eye travels round to the right, next comes the Nevada Fall (Vernal is not seen); then in succession the peaks on the opposite side of the valley; Glacier Point, Sentinel Dome, Sentinel Rock, Cathedral Spires, and Cathedral Rock; then, crossing the valley, and behind us, is El Capitan. In the distance, the peaks of the Sierra, Mt. Hoffman, Cathedral Peak, Cloud’s Rest, Mt. Starr King, Mt. Clark, and Ostrander’s Rocks are seen. Below, the whole valley, like a green carpet, and Merced River, like a beautiful vine, winding through.

We remained and enjoyed the view by sunlight, by twilight, and by moonlight. We then built a huge fire, on the extreme summit. Instantly answering fires were built in almost every part of the valley. We shouted and received answer. We fired guns and pistols, and heard reports in return. I counted the time between flash and report, and found it 9-10 seconds. This would make the distance about two miles, in an air line.

About 8 P. M. went back to camp and supper, and immediately alter, to bed. During the night some of the horses, not having been staked, wandered away, and some of the party, Soulé, Hawkins, and Cobb, were out two hours, recovering them. They found them several miles on their way back to the fat pasture of Bridal Veil meadow. My own horse had been securely staked. On my fragrant, elastic bed of spruce boughs, and wrapped head and ears in my blankets, I knew nothing of all this until morning.

Coming out of the Yosemite to-day, Mr. Muir pointed out to me, and I examined, the Torreya. Fruit solitary, at extreme end of spray, nearly the color, shape, and size of a green-gage plum, and yet a conifer. The morphology of the Kit would be interesting.

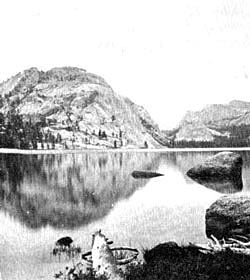

The Heart of the Sierras — Lake Tenaya |

Got up at daybreak this morning much refreshed. I am cook again to-day. My bread this morning was voted excellent. Indeed, it was as light and spongy as any bread I ever ate.

About 12 M. we saw a shepherd’s camp, and rode up in hopes of buying a sheep. No one at home, but there is much sheep meat hanging about and drying. As we came nearer, a delicious fragrance assailed our nostrils, and set our salivaries in action. "A premonitory moistening overflowed my nether lip." What could it be? Here is a pot nearly buried in the hot ashes, and closely covered. Wonder what is in it? Let us see.

On removing the cover, a fragrant steam arose, which fairly overcame the scruples of several of the parry. Mutton stew, deliciously seasoned! Mr. Muir, who had been a shepherd himself, and had attended sheep here last year, and became thoroughly acquainted with shepherds’ habits, assured us that we might eat without compunction—that the shepherd would be pleased rather than displeased—that they had more mutton than they knew what to do with.

Upon this assurance we fell to, for we were very hungry, and the stew quickly disappeared. We all declared, and will always believe, that there never was such mutton stew made in this world before. While we were yet wiping our mustaches (such as had that ornament), the shepherd appeared, and was highly amused and pleased at our extravagant praises of his stew.

Our appetites were, however, not yet half appeased. We went on a little farther and stopped for noon at a small open meadow. While I was cooking dinner, Hawkins bought and butchered a fat sheep. There are thousands of sheep in this region. We expect to live upon mutton until we cross the Sierra.

This afternoon we went on to Lake Tenaya. The trail is very blind, in most places detectable only by the blazing of trees, and very rough. We traveled most of the way on a high ridge. When about two miles of our destination, from the brow of the mountain ridge upon which we had been traveling, Lake Tenaya burst upon our delighted vision, its placid surface set like a gem amongst magnificent mountains, the most conspicuous of which are Mt. Hoffman group on the left, and Cathedral Peak beyond the lake.

From this point we descended to the margin of the lake, and encamped at 5 P. M. on the lower end of the lake, in a fine grove of tamaracks, near an extensive and beautiful meadow. We built an immense fire, and had a fine supper of excellent bread and delicious mutton. Our appetites were excellent; we ate up entirely one hind-quarter of mutton, and wanted more.

After supper, I went with Mr. Muir and sat on a high rock, jutting into the lake. It was full moon. I never saw a more delightful scene. This little lake, one mile long and a half mile wide, is actually embosomed in the mountains, being surrounded by rocky eminences two thousand feet high, of the most picturesque forms, which come down to the very water’s edge.

The deep stillness of the night; the silvery light and deep shadows of the mountains; the reflection on the water, broken into thousands of glittering points by the ruffled surface; the gentle lapping of the wavelets upon the rocky shore—all these seemed exquisitely harmonized with each other, and the grand harmony made answering music in our hearts. Gradually the lake surface became quiet and mirror-like, and the exquisite surrounding scenery was seen double. For an hour we remained sitting in silent enjoyment of this delicious scene, which we reluctantly left to go to bed. Tenaya Lake is about eight thousand feet above sea-level. The night air, therefore, is very cool.

I noticed in many places to-day, especially as we approached Lake Tenaya, the polishings and scorings of ancient glaciers. In many places we found broad, flat masses so polished that our horses could hardly maintain their footing in passing over them. It is wonderful that in granite so decomposable these old glacial surfaces should remain as fresh as the day they were left by the glacier. But if ever the polished surface scales off then the disintegration proceeds as usual. The destruction of these surfaces by scaling, is, in fact, continually going on.

Whitney thinks the polished surface is hardened by pressure of the glacier. I cannot think so. The smoothing, I think, prevents the retention of water, and thus prevents the rotting. Like the rusting of iron, which is hastened by roughness, and still more by rust, and retarded or even prevented by cleaning and polishing, so rotting of rock is hastened by roughness, and still more by commencing to rot, and retarded or prevented by grinding down to the sound rock and then polishing.

To-day, while cooking midday meal, the wind was high, and the fire furious. I singed my whiskers and mustache, and badly burned my hand with boiling-hot bacon fat.

AUGUST 10

Early start this morning for Soda Springs and Mt. Dana. Phelps and his mare entertained us while getting off this morning with an amusing bucking scene. The interesting performance ended with the grand climacteric feat of flying head foremost over the head of the horse, turning a somersault in the air, and alighting safely on the back. After this exhilarating diversion, we proceeded on our way, following the trail on the right hand of the lake.

Onward we go, in single file, I leading the pack, over the roughest and most precipitous trail (if trail it can be called) I ever saw. At one moment we lean forward, holding to the horse’s mane, until our noses are between the horse’s ears; at the next, we stand in the stirrups, with our backs leaning hard against the roll of blankets behind the saddle. Thus we pass, dividing our attention between the difficulties of the way and the magnificence of the scenery, until 12 M., when we reached Soda Springs, in the splendid meadows of the Upper Tuolumne River.

Our trail this morning has been up the Tenaya Cañon, over the divide, and into the Tuolumne Valley. There is abundant evidence of an immense former glacier, coming from Mt. Dana and Mt. Lyell group, filling the Tuolumne Valley, overrunning the divide, and sending a branch down the Tenaya Cañon. The rocks in and about Tenaya Cañon are everywhere scored and polished. We had to dismount and lead over some of these polished surfaces. The horses’ feet slipped and sprawled in every direction, but none fell.

A conspicuous feature of the scenery on Lake Tenaya is a granite knob, eight hundred feet high, at the upper end of the lake, and in the middle of the cañon. This knob is bare, destitute of vegetation, round and polished to the very top. It has evidently been enveloped in the icy mass, and its shape has been determined by it. We observed similar scorings and polishings on the sides of the cañon, to an equal and much greater height.

Splendid view of the double peaks of the Cathedral, from Tenaya Lake and from the trail Looking back from the trail soon after leaving the lake, we saw a conspicuous and very picturesque peak with a vast amphitheater, with precipitous sides, to the north, filled with a grand mass of snow, evidently the fountain of an ancient tributary of the Tenaya Glacier. We called this Coliseum Peak. [Note in edition of 1900: This is sometimes called Tenaya Peak.] So let it be called hereafter, to the end of time.

The Tuolumne meadow is a beautiful grassy plain of great extent, thickly enameled with flowers, and surrounded with the most magnificent scenery. Conspicuous amongst the hundreds of peaks visible are Mt. Dana, with its grand symmetrical outline, and purplish red color; Mt. Gibbs, of gray granite; Mt. Lyell and its group of peaks, upon which great masses of snow still lie; and the wonderfully picturesque group of sharp, inaccessible peaks (viz: Unicorn Peak, Cathedral Peaks, etc.), forming the Cathedral group.

Soda Springs is situated on the northern margin of the Tuolumne meadow. It consists of several springs of ice-cold water, bubbling up from the top of a low reddish mound. Each spring itself issues from the top of a small subordinate mound. The mound consists of carbonate of lime, colored with iron deposited from the water. The water contains principally carbonates of lime and iron, dissolved in excess of carbonic acid, which escapes in large quantities, in bubbles. It possibly, also, contains carbonate of soda. It is very pungent, and delightful to the taste. Before dinner we took a swim in the ice-cold water of the Tuolumne River.

About 3 P. M. commenced saddling up, intending to go on to Mt. Dana. Heavy clouds have been gathering for some time past. Low mutterings of thunder have also been heard. But we had already been so accustomed to the same, without rain, in the Yosemite, that we thought nothing of it. We had already saddled, and some had mounted, when the storm burst upon us. "Our provisions—sugar, tea, salt, flour, must be kept dry!" shouted Hawkins. We hastily dismounted, constructed a sort of shed of blankets and india-rubber cloths, and threw our provisions under It.

Now commenced peal after peal of thunder in an almost continuous roar, and floods of rain. We all crept under the temporary shed, but not before we had gotten pretty well soaked. So much delayed that we were now debating—after the rain—whether we had not better remain here over night. Some were urgent for pushing on, others equally so for staying.

Just at this juncture, when the debate ran high, a shout, "Hurrah!" turned all eyes in the same direction. Hawkins and Mr. Muir had scraped up the dry leaves underneath a huge prostrate tree, set fire and piled on fuel, and already, see! a glorious blaze! This incident decided the question at once. With a shout, we all ran for fuel, and piled on log after log, until the blaze rose twenty feet high. Before, shivering, crouching, and miserable; now, joyous and gloriously happy.

The storm did not last more than an hour. After it, the sun came out and flooded all the landscape with liquid gold. I sat alone at some distance from the camp, and watched the successive changes of the scene—first, the blazing sunlight flooding meadow and mountain; then the golden light on mountain peaks, and then the lengthening shadows on the valley; then a roseate bloom diffused over sky and air, over mountain and meadow. Oh! how exquisite! I never saw the like before. Last, the creeping shadow of night, descending and enveloping all.

The Tuolumne meadows are celebrated for their fine pasturage. Some twelve to fifteen thousand sheep are now pastured here. They are divided into flocks of about two thousand five hundred to three thousand. I was greatly interested in watching the management of these flocks, each by means of a dog. The intelligence of the dog is perhaps nowhere more conspicuous.

The sheep we bought yesterday is entirely gone—eaten up in one day. We bought another here, a fine, large, fat one. In an hour it was butchered, quartered, and a portion on the fire, cooking. After a very hearty supper, we hung up our blankets about our camp-fire to dry, while we ourselves gathered around it to enjoy its delicious warmth. By request of the party, I gave a familiar lecture, or rather talk, on the subject of glaciers, and the glacial phenomena we had seen on the way.

LECTURE ON GLACIERS AND THE GLACIAL PHENOMENA OF THE SIERRAS. (ABSTRACT)

In certain countries, where the mountains rise into the region of perpetual snow, and where other conditions, especially abundant moisture, are present, we find enormous masses of ice occupying the valleys, extending far below the snow-cap, and slowly moving downward. Such moving icy extensions of the perpetual snow-cap are called glaciers.

It is easy to see that both the existence of glaciers and their downward motion is necessary to satisfy the demands of the great universal Law of Circulation. For in countries where glaciers exist, the amount of snow which falls on mountain tops is far greater than the waste of the same by melting and evaporation in the same region. The snow, therefore, would accumulate without limit if it did not move down to lower regions, where the excess is melted and returned again to the general circulation of meteoric waters.

In the Alps, glaciers are now found ten to fifteen miles long, one to three miles wide, and five hundred to six hundred feet thick. They often reach four thousand feet below the snow-level, and their rate of motion varies from a few inches to several feet per day. In grander mountains, such as the Himalayas and Andes, they are found of much greater size; while in Greenland and the Antarctic continent the whole surface of the country is completely covered, two thousand to three thousand feet deep, with an ice sheet, molding itself on the inequalities of surface, and moving slowly seaward, to break off there into masses which form icebergs. The icy instead of snowy condition of glaciers is the result of pressure, together with successive thawings and freezings. Snow is thus slowly compacted into glacier-ice.

Although glaciers are in continual motion downward, yet the lower end, or foot, never reaches below a certain point; and under unchanging conditions, this point remains fixed. The reason is obvious: The glacier may be regarded as being under the influence of two opposite forces; the downward motion tending ever to lengthen, and the melting tending ever to shorten it. High up the mountain the motion is in excess, but as the melting power of sun and air increases downward, there must be a place where the motion and the melting balance each other. At this point will be found the foot. It is called the lower limit of the glacier.

Its position, of course, varies in different countries, and many even reach the sea-coast, in which case icebergs are formed. Annual changes of temperature do not affect the position of the foot of the glacier, but secular changes cause it to advance or retreat. During periods of increasing cold and moisture, the foot advances, pushing before it the accumulating débris. During periods of increasing heat and dryness it retreats, leaving its previously accumulated débris lower down the valley. But whether the foot of the glacier be stationary, or advancing or retreating, the matter of the glacier, and therefore all the débris lying on its surface, is in continual motion downward. Since glaciers we limited by melting, it is evident that a river springs from the foot of every glacier.

Moraines.—On the surface, and about the foot of glaciers, are always found immense piles of heterogeneous débris, consisting of rock fragments of all sizes, mixed with earth. These are called moraines. On the surface, the most usual form and place is a long heap, often twenty to fifty feet high, along each side, next the bounding cliffs. These are called lateral moraines. They are ruins of the crumbling cliffs on each side, drawn out into continuous line by the motion of the glacier.

If glaciers are without tributaries, these lateral moraines are all the débris on their surface; but if glaciers have tributaries, then the two interior lateral moraines of the tributaries are carried down the middle of the glacier, as a medial moraine. There is a medial moraine for every tributary. In complicated glaciers, therefore, the whole surface may be nearly covered with débris. All these materials, whether lateral or medial, are borne slowly onward by the motion of the glacier, and finally deposited at its foot, in the form of a huge, irregularly crescentic pile of débris known as the terminal moraine. If a glacier runs from a rocky gorge out on a level plain, then the lateral moraines may be dropped on either side, forming parallel débris piles, confining the glacier.

Laws of Glacial Motion.—Glaciers do not slide down their beds, like solid bodies, but run down in the manner of a body half solid, half liquid; i. e., in the manner of a stream of stiffly viscous substance. Thus, while a glacier slides over its bed, yet the upper layers move faster, and therefore slide over the lower layers. Again, while the whole mass moves down, rubbing on the bounding sides, yet the middle portions move faster, and therefore slide on the marginal portions.

Lastly, while a glacier moves over smaller inequalities of bed and bank like a solid, yet it conforms to and molds itself upon the larger inequalities, like a liquid. Also, its motion down steep slopes is greater than over level reaches. Thus, glaciers like rivers, have their narrows and their lakes, their rapids and their stiller portions, their deeps and their shallows. In a word, a glacier is a stream, its motion is viscoid, and, for the practical purposes of the geologist, it may be regarded as a very stiffly viscous body.

Glaciers as a Geological Agent.—Glaciers, like rivers, wear away the surfaces over which they pass; transport materials and deposit them in their course, or at their termination. But in all these respects the effects of glacial action are very characteristic, and cannot be mistaken for those of any other agent.

Erosion.—The cutting or wearing power of glaciers is very great; not only on account of their great weight, but also because they carry, fixed firmly in their lower surfaces, and therefore between themselves and their beds, rock fragments of all sizes, which act as their graving tools. These fragments are partly torn off from their rocky beds in their course, but principally consist of top-débris, which find their way to the bottom through fissures, or else are engulfed in the viscous mass on the sides.

Armed with these graving tools, a glacier behaves towards smaller inequalities like a solid body, planing them down to a smooth surface, and marking the smooth surface thus made with straight parallel scratches. But to large inequalities it behaves like a viscous liquid, conforming to their surfaces, while it smooths and scratches them. It molds itself upon large prominences and scoops out large hollows, at the same time smoothing, rounding and scoring them. These smooth, rounded, scored surfaces, and these scooped-out rock basins, are very characteristic of glacial action. We have passed over many such smooth surfaces this morning. The scooped-out rock basins, when left by the retreating glacier, become beautiful lakes. Lake Tenaya is probably such a lake.

Transportation.—The carrying power of river currents has a definite relation to velocity. To carry rock fragments, of many tons weight, requires an almost incredible velocity, Glaciers, on the contrary, carry on their surfaces, with equal ease, fragments of all sizes, even up to hundreds of tons weight. Again, bowlders carried by water currents are always bruised and rounded, while glaciers carry them safely and lay them down in their original angular condition. Again, river currents always leave bowlders in secure position, while glaciers may set them down gently, by the melting of the ice, in insecure positions, as balanced stones. Therefore large angular bowlders, different from the country rock, and especially if in insecure positions, are very characteristic of glacial action.

Deposit—Terminal Moraine.—As already seen, all materials accumulated on the surface of a glacier, or pushed along on the bed beneath, find their final resting-place at the foot, and there form the terminal moraine. If a glacier recedes, it leaves its terminal moraine, and makes a new one at the new position of its foot. Terminal moraines therefore, are very characteristic signs of the former position of a glacier foot. They are recognized by their irregular crescentic form, the mixed nature of their materials, and the entire want of stratification or sorting. Behind the terminal moraines of retired glaciers accumulate the waters of the river which flows from its foot, and thus again, form lakes. Glacial lakes, i. e., lakes formed by the action of former glaciers are, therefore, of two kinds, viz: (1) The filling of scooped-out rock basins; (2) the accumulation of water behind old terminal moraines. The first are found, usually, high up; the second, lower down the old glacial valleys.

Glacial Epoch in California.—It is by means of these signs that geologists have proved that at a period very ancient in human but very recent in geological chronology, glaciers were greatly extended in regions where they still exist, and existed in great numbers and size in regions where they no longer exist. This period is called the Glacial Epoch. Now, during this glacial epoch, the whole of the high Sierra region was covered with an ice-mantle, from which ran great glacial streams far down the slopes on either side.

We have already seen evidences of some of these ancient glaciers on this, the western, slope. After crossing Mono Pass, we will doubtless see evidences of those which occupied the eastern slope. In our ride yesterday and to-day, we crossed the track of some of these ancient glaciers. From where we now sit, we can follow with the eye their pathways. A great glacier (the Tuolumne Glacier), once filled this beautiful meadow, and its icy flood covered the spot where we now sit.

It was fed by several tributaries. One from Mt. Lyell, another from Mono Pass and still another from Mount Dana, which, uniting just above Soda Springs, the swollen stream enveloped yonder granite knobs five hundred feet high, standing directly in its path, smoothing and rounding them on every side, and leaving them in form like a turtle’s back; then coming farther down overflowed its banks at the lowest point of yonder ridge—one thousand feet high—which we crossed this morning, and after sending an overflow stream down Tenaya Cañon the main stream passed on down the Tuolumne Cañon into and beyond Hetch Hetchy Valley. From its head fountain, in Mt. Lyell, this glacier may be traced forty miles.

The overflow branch which passed down the Tenaya Cañon, after gathering tributaries from the region of Cathedral Peaks, and enveloping, smoothing, and rounding the grand granite knobs which we saw this morning just above Lake Tenaya, scooped out that lake basin, and swept on its way to the Yosemite. There it united with other streams from Little Yosemite and Nevada Cañons, and from Illilouette, to form the great Yosemite Glacier, which probably filled that valley to the brim and passed on down the cañon of the Merced.

This glacier, in its subsequent retreat, left many imperfect terminal moraines, which are still detectable as rough débris piles, just below the meadows. Behind these moraines accumulated water, forming lakes, which have gradually filled up and formed meadows. Some, as Mirror Lake, have not yet filled up. The meadows of Yosemite, and the lakes and meadows of Tenaya Fork, upon which our horses grazed while we were at University Camp, were formed in this way. You must have observed that these lakes and meadows are separated by higher ground, composed of coarse débris. All the lakes and meadows of this High Sierra region were formed in this way. The region of good grazing is also the region of former glaciers.

Erosion in High Sierra Region.—The erosion to which this whole High Sierra region has been subjected, in geological times, is something almost incredible. It is a common popular notion that mountain peaks are upheaved. No one can look about him observantly in this high Sierra region, and retain such a notion. Every peak and valley now within our view—all that constitutes the grand scenery upon which we now look, is the result wholly of erosion—of mountain sculpture.

Mountain chains are, indeed, formed by igneous agency; but these are afterwards sculptured into forms of beauty. But even this gives as yet no adequate idea of the immensity of this erosion; not only are all the grand peaks now within view, Cathedral Peaks, Unicorn Peak, Mt. Lyell, Mt. Gibbs, Mt. Dana, the result of simple inequality of erosion, but it is almost certain that the slates which form the foothills, and over whose upturned edges we passed, from Snelling to Clark’s, and whose edges we again see, forming the highest crests on the very margin of the eastern slope, originally covered the granite of this whole region many thousand feet deep. Erosion has removed it entirely, and bitten deep into the underlying granite. Now, you are not to imagine that the whole, but certainly a large portion of this erosion, and the final touches of this sculpturing, has been accomplished by the glacial action which we have endeavored to explain.

About 9 P. M., our clothing still damp, we rolled ourselves in our damp blankets, lay upon the still wet ground, and went to sleep. I slept well and suffered no inconvenience.

To any one wishing really to enjoy camp life among the high Sierra, I know no place more delightful than Soda Springs. Being about nine thousand feet above the sea, the air is deliciously cool and bracing. The water, whether of the spring or of the river, is almost ice-cold, and the former a gentle tonic. The scenery is nowhere more glorious. Add to this, inexhaustible pasturage for horses, and plenty of mutton, and what more can pleasure seekers want?

AUGUST 11

As we intended going only to the foot of Mt. Dana, a distance of about eleven miles, we did not hurry this morning. The mutton gotten yesterday must be securely packed; we did not get started until 9 A. M. Trail very blind. Lost it a dozen times, and had to scatter to find it each time. Saw again this morning magnificent evidences of the Tuolumne Glacier. Among the most remarkable, several smooth, rounded knobs of granite, eight hundred to one thousand feet high, with long slope up the valley, and steep slope down the valley, evidently their whole form determined by an enveloping glacier.

About 2 P. M., as we were looking out for a camping-ground, a thunder-storm again burst upon us. We hurried on, searching among the huge bowlders (probably glacial bowlders), to find a place of shelter for our provisions and ourselves. At last we found a huge bowlder which overhung on one side, leaning against a large tree. The roaring of the coming storm grows louder and louder, the pattering of rain already commences. "Quick! quick!!"

In a few seconds the pack was unsaddled, and provisions thrown under shelter. Then rolls of blankets quickly thrown after them; then the horses unsaddled and tied; then, at last, we ourselves, though already wet, crowded under. It was an interesting and somewhat amusing sight. All our provisions and blanket rolls and eleven men packed away, actually piled upon one another, under a rock which did not project more than two and a half feet.

I wish I could draw a picture of the scene; the huge rock with its dark recess; the living, squirming mass, piled confusedly beneath; the magnificent forest of grand trees; the black clouds; the constant gleams of lightning, revealing the scarcely visible faces; the peals of thunder, and the floods of rain, pouring from the rock on the projecting feet and knees of those whose legs were inconveniently long, or even on the heads and backs of some who were less favored in position.

In about an hour the storm passed, the sun again came out, and we selected camp. Beneath a huge prostrate tree we soon started a fire, and piled log upon log, until the flame, leaping upwards, seemed determined to overtop the huge pines around. Ah! what a joy is a huge camp-fire! not only its delicious warmth to one wet with rain in this high cool region, but its cheerful light, its joyous crackling and cracking, its frantic dancing and leaping! How the heart warms, and brightens, and rejoices, and leaps, in concert with the camp-fire!

We are here nearly ten thousand feet above sea-leveL Our appetites are ravenous. We eat up a sheep in a day; a sack (one hundred pounds) of flour lasts us five or six days. Nights are so cool that we are compelled to make huge fires, and sleep near the fire to keep warm.

Our camp here is a most delightful one, in the midst 01 grand trees and huge bowlders—a meadow hard by, of course, for our horses. By stepping into the meadow, we see looming up very near us, on the south, the grand form of Mt. Gibbes, and on the north, the still grander form of Mt. Dana. After supper, and dishwashing, and horse-tending, and fire-replenishing, the young men gathered around me, and I gave them the following:

LECTURE ON DEPOSITS IN CARBONATE SPRINGS

You saw yesterday and this morning the bubbles of gas which rise in such abundance to the surface of Soda Spring. You observed the pleasant pungent taste of the water, and you have doubtless associated both of these with the presence of carbonic acid. But there is another fact which probably you have not associated with the presence of this gas, viz., the deposit of a reddish substance. This reddish substance, which forms the mound from the top of which the spring bubbles, is carbonate of lime, colored with iron oxide. This deposit is very common in carbonated springs. I wish to explain it to you.

Remember then: 1st, that lime carbonate and metallic carbonates are insoluble in pure water, but slightly soluble in water containing carbonic acid; 2d, that the amount of carbonates taken up by water is proportionate to the amount of carbonic acid in solution; 3d, that the amount of carbonic acid which may be taken in solution is proportioned to the pressure. Now, all spring water contains a small quantity of carbonic acid, derived from the air, and will therefore dissolve limestone (carbonate of lime); but the quantity taken up by such waters is so small that it will not deposit except by drying. Such are not called carbonated springs.

But there are, also, subterranean sources of carbonic acid, especially in volcanic districts. Now, if percolating water come in contact with such carbonic acid—being under heavy pressure—it takes up larger quantities of the gas. If such waters come to the surface, the pressure being removed, the gas escapes in bubbles. This is a carbonated spring.

If further, the subterranean water thus highly charged with carbonic acid comes in contact with limestone or rocks of any kind containing carbonate of lime, it dissolves a proportionately large amount of this carbonate, and when it comes to the surface, the escape of the carbonic acid causes the limestone to deposit, and hence this material accumulates immediately about the spring, and in the course of the stream issuing from the spring.

The kind of material depends upon the manner of deposit and upon the presence or absence of iron. If the deposit is tumultuous, the material is spongy, or even pulverulent; if quiet, it is dense. If no iron be present, the deposit is white as marble; but if iron be present, its oxidation will color the deposit yellow, or brown, or reddish. If the amount of iron be variable, the stone formed will be beautifully striped. Suisun marble is an example of a beautifully striped stone, deposited in this way in a former geological epoch.

I have said that such springs are most common in volcanic districts. They are, therefore, most commonly warm. Soda Springs, however, is not in a volcanic district. In our travels in the volcanic region on the other side of the Sierra we will find, probably, several others. At one time these springs were far more abundant in California than they are now.

Continue to August 12-24, 1870 • Up to Top • Index

Source: Translated from SGML by Dan Anderson from the Library of Congress American Memory Collection, "The Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920."