[click to enlarge]

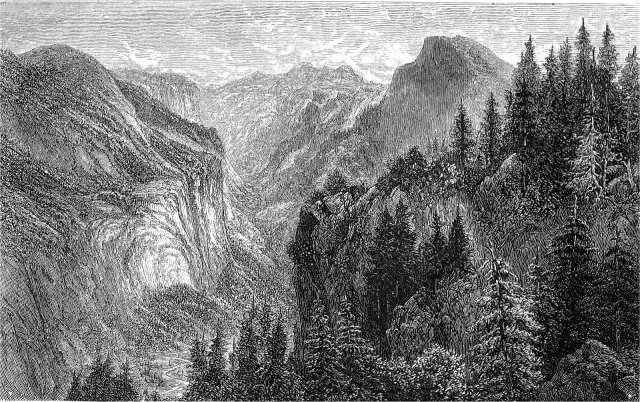

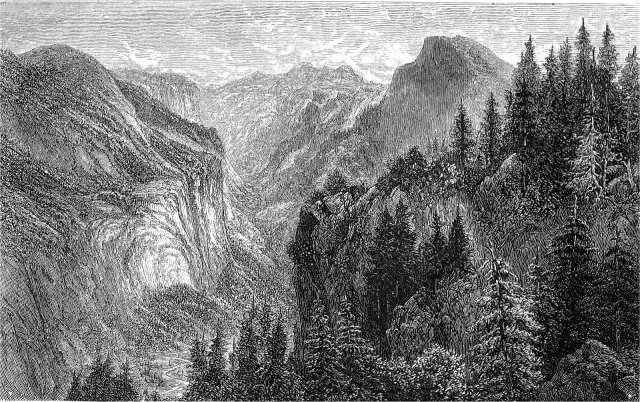

TENAYA CAŅON—YO-SEMITE VALLEY

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Atlantic to the Pacific > The Geysers >

Next: Santa Clara Valley • Contents • Previous: San Francisco

The Geysers.—On May 23 I set out for a tour through Napa Valley to the famous hot springs. Taking the 4 o’clock boat, I had a delightful sail through the bay to Vallejo. As we leave the city, we pass in sight of the Golden Gate and Fort Point, alongside of Alcatraz and Angel Island, thence through the Straits of San Quentin into the Bay of San Pablo. This is a broad expanse of water, bounded on all sides by high hills, save to the north-east, where Mare Island forms the harbour of Vallejo, and where begin the Straits of Carquinez, opening into Suisun Bay, into which empty the great rivers Sacramento and San Joaquin. Upon Mare Island are erected the buildings connected with the Navy-yard of the United States Government, including extensive machine-shops and other workshops, a hospital, storehouses, a magazine for powder, and houses and quarters for the officers and men. In the river facing Vallejo have been built fine docks and wharves, which make safe landings for the largest vessels; while the harbour is of a size sufficient to accommodate all the fleet of the country if necessary. Here lies the old ‘Kearsage,’ whose crumbling frame and rotting timbers could now ill stand a battle, but whose every plank has been made famous by that memorable fight with the Alabama.

Vallejo lies a little way from the landing, has the only steam-elevator in the State, some good buildings and many poor ones, and looks very old. It is only kept alive by the trade of the soldiers and sailors; but its people still cherish a fancy that it is to be a great city. Of this place I cannot speak much praise; for, with all its natural advantages of a fine harbour and government patronage, it seems to be asleep—almost dead. Near the city is the terminus of a railroad called the California Pacific, which is by far the pleasantest route between Sacramento and San Francisco.

Napa Valley.—This is one of the most beautiful and fertile of those great plains which lie between the mountain-ranges of this State, being the eastern one of three —Sonoma, Petaluma, and Napa—which start from the bay, and take a general north-west course. From Vallejo to Napa City the road follows Napa River. The country around is pleasing, the ranches well farmed, and the buildings better than in most parts of the State. This Valley is productive in wheat, barley, corn, and grapes, yielding immense crops. Napa City has about 4,000 people, lies upon the west bank of the river, is well laid out, contains many stores, two banks, has two daily papers, and is one of the most flourishing towns. A little steamer runs up to it from San Francisco. The climate is very agreeable: the cold winds of San Francisco are here modified into soft and balmy breezes. About five miles from the city are soda-springs, where they dip up soda-water, put it into bottles, surcharge it a little more with gas collected from the spring, and send it away to be drunk by all. No fountains, no sulphuric acid, no limestone and intricate machinery, are here needed to manufacture soda; for Nature has her own laboratory, where she makes this ‘delicious drink.’ I found in one of the gardens here finer roses, and by far finer pinks (both carnation and picotee), than I ever saw growing in the open air. Here were all the tea-roses, great beds of verbenas, and pinks in almost endless variety, and in size equal to Henderson’s choicest blooms. There was also a fine collection of conifers, among them the Sequoia, as well as many deciduous trees. All that is needed to make this one of the handsomest of gardens is a good lawn of fresh-growing grasses. The roses of Napa are the finest I have found; the foliage entirely free from all insects and worms, and giving, I am told, blossoms every month in the year.

I next visited St. Helena and Calistoga. The ride to the first-named town is even more interesting than that to Napa. The grape-lands begin here; and we see vineyards of twenty, fifty, and even a hundred acres, now in all the luxuriance of setting fruit. Large wine-houses are seen along the line; and extensive farmhouses dot the landscape, embowered among the beautiful trees for which this Valley is famed. Many of the wealthy ‘Friscans’ have their summer residences here, where they are protected against the cold winds which make the city climate so disagreeable, especially in summer. Among the many fine places, that of Woodward’s seemed to be superior in its appointments and the great neatness which prevailed in every department. I noticed that in some places the apple-orchards were badly stripped of their leaves by the caterpillar, but was told that it was quite uncommon. As we go North, the Valley narrows so perceptibly that it seems an easy walk between the hills which bound it on either side. All things considered, this is the best farming-section which I have seen.

White Sulphur Springs.—At the pretty little town of St. Helena we take a carriage for the Springs. They are some two miles up a beautiful caņon; and, as I drove up to the hotel, I felt assured that I had found the gem of California resorts. There are nine of these springs, the largest one of which discharges 6,144 wine gallons per day. They were first discovered in 1850, having been a favourite resort for the Indians, where they came to drink or to bathe in their warm waters. Around the pools, where the water gushes from the ground, the Indians erected little huts of skins and barks, and in them sweated themselves in the hot sulphur vapours. The waters of these springs are warmer than most of the sulphur springs of Europe. They contain, beside sulphur, carbonate of lime, magnesia, sulphate of soda, salt, lime, &c. Many sufferers from rheumatism and skin diseases told me they found great relief by the use of these waters.

From the surrounding heights fine views are had; and the various trails which have been cut lead by easy grades to the tops of mountains and along steep precipices. The caņon in which the springs are located is a little gulch between hills, in which there is little room to spare, for the hotel buildings occupy nearly all the space. The hillsides are occupied by pretty cottages and sleeping-houses; for here they build summer hotels upon a plan which an inclement climate would forbid. The hotel is a building containing the office and a common parlour, adjoining neatly-arranged bath-rooms, into which the waters from the spring are conducted; across the drive-way way is the dining-room, and to the right the billiard-hall; the kitchens are farther back; and up the gulch are several buildings, each divided into three sections, for sleeping-rooms. To the left of the hotel, on the plateau (upon which stood the finest summer hotel in the State, but which was unfortunately burned), have been erected some dozen single cottages. All the occupants of these various cottages take their meals at the common dining-hall, or gather in the common parlour after dinner, but can at any time remain in their own cottage as quietly and as secluded as they desire. The grounds are laid out with taste; and the most scrupulous neatness is shown on every hand. Up the gulch a little way is a grove of seven redwood-trees, the only specimens of this tree in many a mile—the only ones I have found since leaving the Truckee region in the Sierras. A stream runs through the estate, in which there is good fishing.

The genius of the place is Mr. John Bremberg, whose position is express-agent, telegraph-operator, writer of the bills of fare, catcher of butterflies, superintendent of the baths, general helpmeet for everybody, and charged with the important duty of making every one happy. To attend to all his duties, of course, John is kept busy; and he rushes here and there, he sweats and foams, but always has a kind word for all. For now it is some little child who wants John to help at her play, and he goes; now some old lady wants John to come and pack up her trunk, and off he goes; or some ‘Spanish beauty’ comes for John to go for a walk, and protect her against snakes, and he goes willingly. He keeps a medicine chest, which has gained him the title of ‘doctor;’ and, as he peers over his gold-bowed spectacles, he does really look wise.

Calistoga Springs.—From St. Helena, a ride of nine miles brings us to the town, Calistoga, the derivation of which is easily perceived—calis, ‘hot,’ and toga, ‘a garment.’ The name was given by a gentleman who had received benefit from the numerous hot sulphur springs here. The ‘Little Geysers,’ as they are called, were used by the Indians, who erected their sweating-huts, here also. The railroad terminates here; and the train which starts from Vallejo upon the arrival of the boat which leaves San Francisco at 4 p.m. reaches Calistoga at 8 in the evening. Hence are wagon-roads, which traverse the great defiles in the mountains, up to the Great Geysers, the Clear Lake, the Petrified Forest, and Mount St. Helena. This mountain rises 4,360 feet above the plain, and was named by the Russians in honour of Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great. A valley near by, and in which the Spanish permitted the Russians of Alaska to come and raise their wheat, is still known as Russian Valley. The town has no other importance than as the railroad station for the ‘Springs,’ which is undoubtedly the ‘Saratoga’ of the West. Here, as at White Sulphur, we have a hotel, and a great number of pretty cottages, the Revere, Occidental, Adelphi, Delevan, &c., arranged in a circle around the central building. Over the springs have been erected fantastic structures, which mar the landscape, but which have been built to please the fancy of the proprietor, Sam Brannan, as he is familiarly called. Mr. Brannan was one of the early pioneers, and has done as much as any one man to develop the resources and advantages of the State. In conversation, he charms you with interesting descriptions of the olden times. To him alone is due whatever Calistoga and its surroundings are to-day; and with lavish hand he has tried to make the place beautiful. But his trees, plants, and vines, gathered from every quarter of the globe, have been a failure; for no plant the roots of which extend more than a foot into the ground will grow here, owing to the heat as well as to the mineral deposits.

Every kind of a bath which Mr. Brannan ever saw, read of, or heard of, he has here reproduced; and it would seem that, by the number, he had counted up the numerous ills of life, and for each prepared his panacea. People from all over the State, and of course all tourists, come here to spend a few days in a climate genial and warm, ranging from 50° Fah. at night to 86° at noon, and but seldom varying from these figures.

The drives through the grounds are delightful. A close examination of the springs reveals their wonderful character; for here are waters from cold to boiling, pouring from the earth within a circuit of an eighth of a mile, and each spring different in the component parts of the water. There is one spring the waters of which, by adding a little pepper and salt, are said to become chicken-soup—at least with as much ‘chicken’ in it as most hotels use in these days.

The Great Geysers.—We are now to visit, by a stage-coach ride over the mountain-road, the greatest wonder of this region. We find that the engineer who built that road, Mr. William Patterson, is to go over it to-day; and we gladly accompany him. We are to be driven in a four-horse coach, by an experienced driver, who does not yield the ribbons even to Foss, that knight of the whip, known all over California. Punctually at 7 we are off, a jolly company of eight, for the wonderful mountain which is on fire; and away through the village we dash. The first ten miles of the road are through a wild and broken country, with hardly a habitation in sight. So far, we are on a county-road: we change horses, and strike off upon a run over the mountain-road proper, and our interest begins. Around the sides of the hills we wind, and up the rocky faces of mountains, where a track has been blasted out of the solid rock, just wide enough for a single carriage. There are places where, if the wheel should turn from its course one-half a foot, the carriage would plunge down a precipice from 2,000 to 3,000 feet. As we ride along, the difficulties which beset the workmen upon the road are pointed out and explained; and at every step a new interest is excited, new views obtained, and new dangers successfully passed. This road was built in 1869, at a cost of $22,000. Its length is seventeen miles. The highest grade is one foot in eight; but the average is one foot in ten. Calistoga is 400 feet above the sea; the summit of the road is 3,600 feet; and the plateau, upon which stands the hotel at the Geysers, is 1,700 feet.

Reaching the summit, we stop to look at as grand a spectacle as eye ever beheld. In front, far, far below us, we see the line of the great Russian Valley; but the mountains beyond seem so near that, at this altitude, the plain of the valley is lost sight of. Around us on every side rise hills piled one upon another; mountain succeeds mountain; the clouds, fleecy and white, as they scud over our heads, seem within reach. Magnificent flowers have made our ride charming; the lupins, the geraniums, and mountain daisies greet us; while the ceanothus, in many colours, adorns the hills. The madrona with its curious bark, the manzanita with its curious-coloured wood, the several varieties of oaks, firs, and cedars, all line our track, and offer here and there refreshing shade.

Our pace up to this point has been slow; but now even the horses seem to know that the rest of the way lies down hill; for at the word they prick up their ears and start upon a run; the driver screams and cracks his whip; the horses catch the excitement, and are soon going at a twenty-mile gait. For the whole eight miles down there is no quarter-mile where, for that distance, the road is straight, but it winds and twists, makes ox-yoke curves, crosses dashing brooks, by dancing waterfalls, and over yawning ravines, always seeming to you that its end has come, but always finding some way out. The eight miles have been done in some thirty minutes; and we are nearing the hotel, where we are to rest for the night within sound of the hissing and roaring steam of the Great Geysers. The genial German, Susenbeth by name, always called ‘Susey’ for short, is at the piazza to welcome us, and help us shake ourselves free of dirt and dust, and assures us that there is no danger from the volcanoes which are easily imagined under our very feet, and ready to burst forth.

As we were running down the mountains, with our well-trained team at their speed, and guided by ‘Corneil Nash,’ I said to him, ‘Are you not sometimes afraid? and how do timid ladies like to ride in this manner?’ ‘Perfectly safe, sir,’ said our knight. ‘Driven here nine years, and no accident. Guess I’ll land you at the hotel all right.’

Our dinner was ready by the time we had the dust brushed from our clothes, and were in trim for table; and, with appetites sharpened by our ride, we filed into as uninviting a dining-room as you could imagine. The walls were of rough boards, whitewashed; and even these were made to look more ugly by hanging upon them the advertisements of several insurance companies, some of which we knew to be no more since the Chicago fire. Our food was an attempt at the preparation of French dishes. There was an abundance of it; but, oh, what peculiar concoctions! Still they all had splendid names. As I told you, ‘Susey’ is a German; his people

[click to enlarge] TENAYA CAŅON—YO-SEMITE VALLEY |

To give an idea of our location, imagine a long building with a verandah in front, from each end of which, but upon opposite sides, extend other buildings, connected with the main one by covered passages. In one of these is the general parlour, in the other the dining-room; while the main building contains the sleeping apartments, which are arranged in two stories and on the two sides, those above as well as below being entered from the verandah. Standing in front of the main building, and looking west, we have the whole extent of Pluton Caņon in view. Geyser Caņon crosses it at right angles, just a little way from the hotel, and is far the larger, a river called Pluton, finding its course through it. All the near-by country is mountainous; and upon the sides, and even around the springs, grow in luxuriance the oak and many woody shrubs, together with the madrona and manzanita. Just at the head of Pluton Caņon a rock juts out into the gorge, which has received the name of ‘The Pulpit.’ Here the caņon divides; and to the right and left rise hills, with sides in places as precipitous and straight as the walls of a building. Looking far away, hills succeed hills; while behind rises a great mountain with the euphonious name of the ‘Hog’s Back.’

At about 4 p.m. we started, under the conduct of a guide, to explore the caņon, and to take a near view of these wonderful springs. While the sun shines in the gorge, the steam which issues from the earth is dissipated by the heat; but in early morning the whole caņon is filled with the clouds of steam, which roll through the gorge, giving it a grand and awful appearance. Crossing Pluton River, we find ourselves at the bottom of the caņon, which at this point is some 35 feet wide, but which narrows, as we look up its whitened surface for half a mile, at an angle of some 45 degrees. There are about 200 fountains, or springs, where steam, to a greater or less extent, issues from the ground. The guide having given to each a long, stout stick, we step upon the bed of mineral deposits, which was once a steaming geyser, but the residuum of which has for years been bleaching under the suns and rains of the recurring seasons. The first spring is the Alum and Iron, the temperature of which is 97° Fahrenheit, and around its sides are incrustations of iron. A little further on we find a spring containing Epsom salts, magnesia, sulphur, iron, &c.—a highly medicated compound, and which has been named the Medicated Geyser Bath. Around us we see beds of crystallised Epsom salts. We pass in order Boiling Alum and Sulphur Spring, Black Sulphur, Epsom Salts Spring, and Boiling Black Sulphur, which roars unceasingly. By far the largest is the Witches’ Caldron, the diameter of which is about 7 feet, and the waters of which boil and bubble, sometimes being thrown 2 feet into the air. It is said that all attempts to find a bottom have failed. We next reach the Intermittent Geyser, which sometimes throws up boiling water 15 feet in the air, but which was moderately calm the day we visited the caņon, the water being thrown only 3 or 4 feet. The Devil’s Inkstand is a small spring, out of which flows a liquid which is a good substitute for ink, and has the quality of being indelible. It is a custom to dip the end of your handkerchief into this spring, that you may carry away the ineffaceable mark of your visit.

We are walking over ground which is honeycombed by extinct geysers; and often our feet sink ankle-deep into the mineral deposits; or, again, we place a foot where the ground is too hot for comfort. As we are obliged sometimes to cross a space where the very earth seems on fire, and to step from stone to stone, between which are boiling, steaming openings, from which arise sulphury fumes so strong as almost to stifle you, it is hard to persuade yourself that you are not in the realms where old Pluto holds sway.

The most wonderful (if one can be placed above another) of these springs is the Steamboat Geyser. It is on the left, and raised 10 to 15 feet above the caņon level. From its many apertures issues steam, resembling in look, and especially in sound, the blowing off of steam in a steamboat. Around this spring, for some distance, are evidences that once the spring or springs extended over a much larger space. Just beyond this we reach the rock called ‘The Pulpit,’ which we saw from the verandah. We climb up there: the guide fires a pistol to let those at the hotel know that we have reached this place in safety. At this point, the caņon makes a division, and we take the right. From these positions we have an extended view of the caņon down its length; and all these springs—even the Steamboat Geyser, the Witches’ Caldron, and those boiling, sulphurous fountains—are seen from above, and, as we gaze, it seems impossible that we could have made our way up among them to this place.

We pass on over the Mountain of Fire, which is covered with orifices from which once poured fire and steam; and around us, within the space of, say, one mile in length, and a few rods in width, we see strata of sulphur, Epsom salts, alum, copperas, yellow ochre, magnesia, cinnabar, ammonia, nitre, tartaric acid, etc. A little further on, we find the Indian Spring, where the Red men used to bring their sick to be healed, and where were found the rude sweating-huts erected by the natives. Here, in 1869, Edwin Forrest received great relief from the use of the waters. The Eye Water Spring has also effected many cures for weak and inflamed eyes.

Next a great whistling attracts our attention; and, with the guide, we hasten on, and soon come to a small aperture, from which the issuing steam is carried into a small iron pipe made like a boy’s whistle, which is thus made to screech fearfully. At this point we perceive that we have been nearing the hotel, although now at a considerable elevation above it, and some distance away. A fine view is had of the surrounding hills; and, after a rest, we make our way down the sides of the mountain, to Geyser Caņon, and along the river to a bridge which spans it, and over this to the hotel.

The guides who accompany us have a fashion of giving the name of every spring as in some way connected with the Devil—as, Devil’s Kitchen, Devil’s Office, Devil’s Punch-Bowl, and many more in equally bad taste. I have avoided these names. If those who have control over this property would have the caņons surveyed and mapped, with the location of the principal springs, and give them names which would designate their properties, much would be done towards making them more generally known and deservedly popular.

As soon as we reached the hotel, I asked the proprietor if he could tell me who discovered these springs. ‘Elliott,’ he said, ‘was the name; and upon an old register, the first the house had, I will show you the entry in his own handwriting.’ Taking from a desk an old book, and turning over its pages, we found, under date of April 1847, the occasion of a visit of Elliott to the springs, the following:—

‘William B. Elliott was the first known visitor to the Geyser Springs, when out on a bear-hunt, and now resides at Clear Lake.’

Under this a friend has written, in trembling hand—

‘Poor fellow! was killed by the Indians at Pyramid Lake, May 1860.’

Thus is told the simple story of the discovery of these wonderful geysers, and the death of the hardy hunter, who modestly calls himself ‘the first known visitor.’

In regard to the causes of these phenomena two theories are advanced—one that they are produced by purely chemical action, and the other by volcanoes. The latter hypothesis requires evidences of volcanic action in the hills and mountains around; and the former seems to attribute to chemical force greater power than we had supposed could be thus produced—as in the great boiling caldron, or in the spring whose waters are sometimes thrown 10 or even 15 feet into the air. As I have before said, the most impressive view of the caņon is had in early morning, just as sunlight appears. Then the whole gorge is filled with billowing vapour, and with the noise of the escaping steam, and the sulphurous odours. It is indeed a fearful spot at this time.

There is another road to the Geysers, by way of Healdsburg and over the summit of the mountain called ‘Hog’s Back.’ By this route more extended views of Russian Valley and River are obtained. The best advice to the tourist is, to go by one road and return by the other. This mountain journey is among the most famous of those made in California, and those who have been to the Geysers will relate in glowing terms their experiences with Foss and his ‘six-in-hand,’ and of having made such sharp turns in the road that the ears of the leaders were for the time being lost to sight.

Reaching the town again we more fully realise the mountain solitude which we have left—a place where the Creator has made it impossible for man to build his cities or for people in great numbers to congregate—a spot inviting to the sick, where springs and fountains pour out health-giving waters.

Next: Santa Clara Valley • Contents • Previous: San Francisco

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/atlantic_to_the_pacific/geysers.html