[click to enlarge]

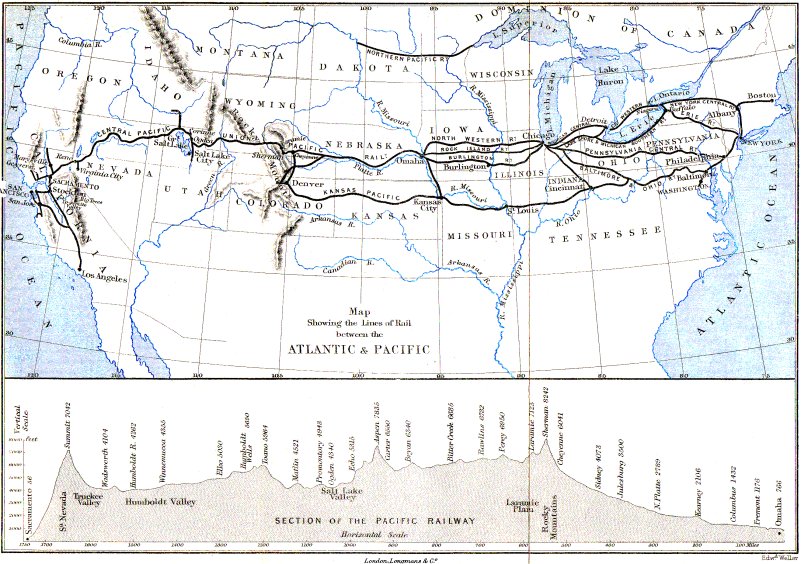

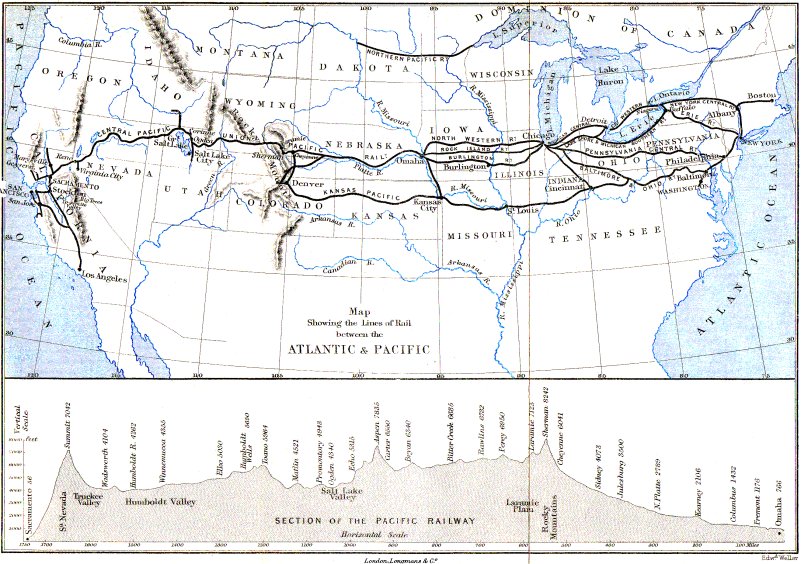

MAP OF RAILWAY LINES BETWEEN THE ATLANTIC AND THE PACIFIC

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Atlantic to the Pacific > Omaha to Salt Lake City >

Next: Mormons • Contents • Previous: Chicago to Omaha

To Salt Lake City.—At Omaha our journey upon the Union Pacific Road begins. But one train leaves daily, running through to the Pacific. Taking a section in a Pullman car, we are entitled to enjoy a drawing-room by day and a bed by night. These cars are comfortable, cleanly, and the attachés, for the most part, polite and accommodating. A throng of strange faces are around us; and all are busily engaged in preparations for the journey.

For three or four miles we pass along the bluffs upon which Omaha is built, and then push out into the open prairie, the fertile lands of Nebraska. A vast plain, dotted here and there with trees, stretches away upon every side. Upon this broad prairie, at long intervals, the cabin of the hardy frontiersman is seen, and now and then a sturdy yeoman, with team of four, breaking up the rich soil for the first planting.

We pass Gilmore, and reach Papillion, where the train from the West awaits us upon the siding. Running along the Elkhorn River, we soon come in view of the hills to the South-West, which bound the Platte Valley; and, just before reaching Fremont, we catch our first view of the Platte River, along the banks of which, now upon the left, and then crossing to the right, we keep our way as far as North Platte. The old emigrant road followed this valley, and crossed the river at old ‘Shinn’s Ferry,’ near the station of Lone Tree.

Our day’s journey brings us to Grand Island, a town named after an island in the Platte. About 1,000 people are gathered here, many connected with the railroad. This is an ‘eating station.’ So far, our ride has been pleasant; and the passengers have generally become acquainted with each other. In our car we have the genial Langford of Montana, who has graphically described the wonders of the Yellowstone Valley; a corps of engineers going out upon the line of the Northern Pacific Railroad to push forward that highway through that hitherto unexplored region; several ladies from my own New England city; gentlemen from New York and Boston, Chicago, and other cities—all enjoying with high spirits the novel experiences, and praising the pure and exhilarating air of the plains.

Two other Pullmans are ahead of our car, each filled with tourists. As the evening came on, the ladies and gentlemen of the ‘Berger-family Troupe’ visited our car, and gave us a concert, both vocal and instrumental. Our car contains an organ, in as good order as the jarring will permit, for our entertainment.

Music sounds upon the prairie, and dies away far over the plains; merry-making and jokes, conversation and reading, pass the time pleasantly till ten o’clock, when we retire, to awake in the morning far out on the plains.

While in Europe, I was often asked if I had seen a ‘wild Indian’—one who carried a tomahawk, painted his face, and wore feathers in his cap. Of course, having rarely been, to my knowledge, within a thousand miles of one of them, I could give but a faint idea of a ‘wild Indian;’ and even here I have not been helped by the sight of the few ‘Pawnee’ who came around us at Grand Island, saying, ‘Good squaw!’ ‘Good Injun!’ ‘Give five cents!’

We have passed through the length of the state of Nebraska, over whose broad acres the fleet antelope runs, and the little prairie-dog digs its holes, and makes its cities. The broad valleys furnish immense grazing-fields; the river-bottoms, rich farming-lands; and the high ground along the road, sites for towns and villages. As the railroad advanced from Omaha, each halting-place, for a time, became the terminus, and was the point where congregated all the roughs and desperadoes. A large town would grow up in a few weeks, and in as short a time pass away, and the deserted houses and cabins now tell of departed glory and ruined business.

Through the state we follow along near the path over which the pioneers of 1848 pushed on to the gold-fields of California, their track being marked here and there by the solitary graves of those whose strength failed.

Between the settlers of the prairies and the Omaha people there is, it seems, a singular antipathy which is somehow connected with a supposed willingness on the part of Omaha to manage the affairs of the rest of the state. The farmers tell you of the great sins of the ‘Omahogs;’ and in the city they sing their own praise, and speak of all the state outside as peopled with ‘Nebraskals.’

At Antelope, 451 miles west of Omaha, we have our first view of the Rocky Mountains, whose snow-capped peaks rise high above the Black Hills, often hiding themselves in the clouds. To these mountains we look anxiously, as they seem impassable; and we await with eager eye to behold the triumph of the engineer who has laid the track for the iron horse over their very summit.

Many who have written of their journey have praised the ‘eating stations,’ as they are called; but I have found so far the food ill cooked and poorly served. A free ticket to dinner may have found aroma in the cup of chicory, comfort in the burned steak, and solace in the black bread. The Company would favour its patrons by reforming this part of their service. Still, do not take a lunch-basket; for it is always in the way. A man who had such an institution, from which every now and then was taken the rich food for the repast, to the evident discomfort of the other passengers, with a devilled ham, a devilled chicken, a devilled turkey and all the fixings, tired at last with carrying about the great basket, exclaimed, ‘Wife, I wish all these devilled things were to the Devil!’

Cheyenne.—We now enter the young Territory of Wyoming. We have passed through the Lodge Pole Creek Valley, which abounds with herds of antelope, and where are found deer, bears, and wolves. Just before we reach Cheyenne, we see directly before us the Rocky Mountains, lifting their huge, dark sides against the sky. Fifty miles to the south of Hillsdale, on the South Platte River, is the often-described Fremont Grove of cottonwood-trees.

Cheyenne is the terminus of the second division of the road (the first extending to North Platte), and is also the junction of the Denver Pacific Railroad. A few houses around the dépôt, the Company’s buildings, and a few scattered over the plain, form the city, where, a few years ago, a defiant mob held sway, and all the roughs from the States found a home. It is five hundred and sixteen miles from Omaha, twelve hundred and sixty from Sacramento, and a hundred and six from Denver. On July 4, 1867, a single house stood on the site of the city, which afterwards, at one time, had six thousand inhabitants. Two newspapers are published here. The people tell you that this is to become a large city, and their expectations will doubtless be realised, though after a longer interval than Western hopefulness is usually prepared for. The abandonment of Fort Russell, a military post which is supplied from Cheyenne, would abate much of the present prosperity of the town, but it must, for a long time, remain the distributing dépôt for freight destined for Colorado and New Mexico.

The Rocky Mountains.—Leaving Cheyenne, we at once begin the ascent of the slope of the Rocky Mountains, by a steep grade; two engines, with difficulty, drawing our train up the mountain-side. We pass the quarries in Granite Cañon, twenty miles from Cheyenne, at 7,298 feet elevation. Wild, rugged, and grand are the peaks which surround us. On every hand float great masses of vapour, through which, now and then, appear the snow-clad mountain-tops. It is a sea of fleecy clouds, to which we seem so near, that we could reach the floating mass. To the south-west, above a broad, dark line, rise the sunlit sides of Long’s Peak. I now realise the truthfulness of Bierstadt’s paintings of the scenery of these hills. The dark, deep shadow, the glistening sides, and the snow-capped peaks, with their granite faces, the stunted growth of pine and cedar, have been faithfully reproduced on his canvas. Snow-banks twelve feet deep are at the road-side; and in the ravines between the mountains are seen huge heaps of snow and ice. By slow stages we reach Sherman, at an elevation of 8,242 feet above tide-water—the highest portion of the Union Pacific line, and the highest railroad elevation in the world. A severe storm prevails; and, if one should desire to paint Desolation, here is the scene for him. The necessities of the road alone keep a few people about the station. In the distance are seen Long’s and Pike’s Peaks, with the Elk Mountains to the north. Though the air is here so rarified that there is some difficulty in breathing, yet, while the train waits the time may be profitably occupied in walking about the station, observing the different rock-formations and the little mountain-flowers, which. with their tiny blooms, greet the eye of the tourist, reminding him of their more gaudy sisters which dwell in the valleys. The profusion of blossoms in the plateau, called Laramie Plain, contrasts with the sterility of the plains beyond. We have here more than 300 distinct varieties of flowering plants,

From Sherman to Laramie the train runs without steam, down a grade of forty-seven and a half feet per mile, under the control of the air-brake. Dale-Creek Bridge is a noble piece of trestle-work, one hundred and twenty-six feet high, spanning a picturesque valley, through which trickles the creek. Now the fantastic red sandstone rocks appear, rearing their spires, domes, and castles from 500 to 1,000 feet above the road-bed. The water, having washed away the loose material, has left the hard rock, whose form has named a station,—Red Buttes. To the south we see the Medicine Bow Mountains, among the deeply serrated sides of which are the springs that feed the Laramie River.

Laramie, the Western terminus of one of the five divisions of the road, and the proposed site of extensive railroad-shops, is a busy place. It is the natural outlet of the Laramie Plain, a well-watered and fertile ‘expanse, which is now opened up as a great grazing field, over which thousands of cattle roam. Several churches, schools, and a newspaper, tell of prosperity.

Laramie is the place where sat the first legally-organized jury of women on record, in the history of the trial and decision of causes under the forms of law. It is said that they all invoked Heaven’s aid in making up their verdict. How far the household duties were neglected during the trial is not told; but their obedient husbands, who staid at home to mind the children, sang away the hours with,—

|

Nice little baby, don’t get in a fury,

‘Cause mamma’s gone to sit on the jury. |

At Laramie the Company have erected a capacious hotel-building, which has become a favourite stopping-place for tourists, who are not obliged to hurry over the road. At this station, and all West of here, we shall see the ‘John Chinamen’ as road-hands. We pass Lookout, Rock Creek, Como, from each of which places the rolling prairies stretch far away. Then we strike into the coal-country. At Carbon Station some 300 men are employed in mining coal for shipment as far East as Omaha. During the night we pass out of this region; and morning finds us upon the banks of Green River, where begins the Little Laramie Plain. Green-river Station is now a deserted city, but was once a noted station on the overland road, from which point many an exploring expedition has started forth. We get a poor breakfast here. The sun has risen brightly, and lights up the deep ravines through which we are to find our way down into the Salt Lake Basin. The country hereabouts is very uninviting, barren hills and sage-bush land meeting the eye on all sides. Passing Bryan station, the next, Granger, is in Utah territory.

On the way from Granger to Evanston it was arranged to hold religious services, the day being Sunday. Friends from the other cars come into ours, and with the conductor, porters, and train-men, fill every seat. The Episcopal service appropriate for the day is read by one of the passengers. After this a sermon is read. The hymn,

| When, Lord, to this our western land, |

is then read; after which a select choir, composed of members of a troupe of travelling minstrels sing,—

| Nearer, my God, to thee, |

and several other familiar tunes, closing with our national hymn. Our services lasted nearly two hours; and the closest attention was given by all, the extraordinary circumstances of the occasion certainly detracting far less than might have been expected from its solemnity.

We dined at Evanston, from bountifully-spread tables, and were soon after at Wahsatch, which is the entrance to Echo Cañon. Passing through a tunnel 770 feet long, we enter the North Fork. Around, the hills rise abruptly on every side, the gloomy cañons dividing them. We see the towering, castle-like rocks which stand up out of the hills; we rush on through the ever-narrowing cañon until it becomes only a mere gorge, down which Echo Creek dashes, marking out the track for the road. It seems that God himself had designed this to be the gateway through which we were to enter the valley. Castle Rock, Hanging Rock, Pulpit Rock, frowning cliffs and receding hills, come in view as the train speeds its way. At the narrowest part of the ravine, on the top of the cliffs, may still be seen the fortifications erected by the Mormons in the year 1857; and, close to the brink, the huge bowlders intended for the destruction of our troops, but, happily, never used, and now only marring the landscape—monuments of folly.

Away to the south now in full view are the snow-clad

[click to enlarge] MAP OF RAILWAY LINES BETWEEN THE ATLANTIC AND THE PACIFIC |

Weber Cañon is now entered; and for miles the track is laid along the banks of a dashing, foaming, angry stream. High mountains bound this ravine on each side, and in many places the road-bed is cut out of the hillside. Every step presents new wonders. The rocks, apparently from the effect of volcanic action, have assumed peculiar forms; the strata, in some places rising vertically from the hills, like huge walls. These serrated rocks at one point are called ‘The Devil’s Slide.’

A thrifty pine, of giant form, marks 1000 miles west from Omaha. There it stands, a solitary sentinel, telling to every passing traveller the same tale of home far away. Occasionally, we catch glimpses of the peculiar yellow stone which has rendered famous large sections far to the North. Granite, slate, conglomerate, sandstone, and limestone, are also seen.

Just where the river is forced between two great walls of rock into a foaming, boiling current which rushes madly on, the road crosses the stream, and we soon emerge into the fertile plain of Salt Lake Valley. The Wahsatch Mountains are now passed, and we see on either side the well-tilled farms of the Mormon settlements. A short ride takes us to Ogden, a town of 4,000 souls, mostly Mormons, and the point of junction of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads. I had decided to visit Salt Lake City, on my way westward, and as Ogden is the point of connexion with the Utah Central Railroad, leading to Salt Lake, I here quitted the pleasant company of those who had been my fellow passengers for three days. Some few of them decided, however, to join me in visiting the city of the ‘Saints.’ We reached our destination in a journey of thirty-six miles, which was accomplished in two hours, the railroad traversing a southerly course along the shore of the Salt Lake.

Next: Mormons • Contents • Previous: Chicago to Omaha

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/atlantic_to_the_pacific/omaha_to_salt_lake.html