[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Big Oak Flat Road > Feeder Roads and Forgotten Towns >

Next: Chinese Camp • Contents • Previous: Knight’s Ferry

East of Knight’s Ferry the freighters, with much swearing and cracking of whips, urged their straining teams over the bulge of the hill and settled down to the job of hating the next five or six miles. This portion of the road was dreaded at most times of the year. In winter the rolling 1000 foot elevation was blasted by chill winds off the snow while the bottomless mud lasted through the spring months. No freight man ever left a brother teamster stranded so it was not unusual to see several great wagons and trailers with their attendant drivers and animals waiting to assist one another past a particularly obnoxious bog hole.1 In midsummer the sun shimmered back from silvery dead grasses and heated to stove-top temperature the dull black lava chunks strewn everywhere. On hot days one could cook an egg on any sun-touched rock.

In the mornings the drivers often saw rattlesnakes dusting themselves in the powdery dirt of the road. The frightened teams would not pass so the teamsters went out to battle and became expert at decapitating the snakes with one crack of a bull whip. A portion of this stretch was known as Devil’s Flat and it had many atttributes not conducive to the peace of mind of a conscientious driver.

Freighting was one of the big industries of California—the foundation of many a fortune. The mining country was rough and widespread; the settlements often isolated; yet the pioneer families must eat and be clothed. The ponderous wagons must find passage across rocky flats, swampy meadows and through rugged and dangerous canyons. Moreover a freighter never found what would now be considered even a fair road. All such construction must be done by hand. A shelf hewn painfully out of a precipitous canyon-side was made only the width of the lumbering vehicles with a foot or two to spare in case the driver wanted to walk back and inspect the lashing of his load. Passing was sometimes an impossibility and was, at other times, accomplished at the ragged verge of eternity. The drivers prevented such an impasse by keeping informed on the probable time that a given outfit might be expected along the road. Ethics took care of most eventualities. The loaded team pulling up-grade was given the best of the situation; was allowed the inside of the road; was not expected to stop. Such an outfit was noisy—wheels pounding on and off of rocks, whips cracking, men cursing, animals snorting. The team coming down the grade stopped just short of the last turnout before a narrow stretch and listened. If advisable it waited. Many of the lead spans of horses or mules wore above their collars a sort of flattened half hoop strung with jangling bells which served as a warning.

The clangor of the bell-team was a stirring sound that tugged at the heart strings of the old-time teamster as the long drawn whistle of a far locomotive heard in the night brings a sharp nostalgia to the superannuated engineer.

A driver’s team was his love, his livelihood and his chief claim to distinction and the teamsters were important people in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. Never as dashing as the stage drivers, a few specimens of whom took pleasure in scaring the Yosemite tourists out of their eye-teeth, but very substantial citizens. Many of them owned their valuable outfits and many were sons of the landed proprietors of the region. Some of the best-known of those who drew freight from the loading levee at Stockton out past the Nightingale and into the mountains were G. L. Rodden, Sandy Campbell, George W. Wilbur, Joe Collins, John Curtin and sons, John Probst who drove twelve oxen and was known throughout the country as “Bull John,” Charles Wagner, Al Clifford, Joseph Mitchell, H. N. Brunson, “Curly” Beith, J. P. Peters, John Fox, Henry Heckman, Gus Lotman (or possibly Lodtmann), Ira Ladd, George McQuade and son, David Libby and “Ace” Bartholomew. Beyond Knight’s Ferry miles of ruined rock fences appear. The magnitude of effort necessary to build them exhausts the imagination, but they are not confined to this district. They are common in the rocky foothills up and down the length of the mining area. Ranchers say that they were originally as much as five feet high and cattle-proof. Some, less high, were used simply as boundary fences for lack of any other material as available. Many were built by Chinese labor.

[click to enlarge] |

More than a mile from the intersection of the road from Knight’s Ferry bridge with Highway 120 a road turns south. It is the modern equivalent of the Willow Springs Road named from free-flowing springs on the old Hodgdon Ranch from whence Willow Springs Creek flows into the Stanislaus River. It was originally the age-old trail of the mountain Indians. During the seasonal powwow at the rancheria of Jose Jesus, Indians from several tribes gathered at what is now Knight’s Ferry by means of this thoroughfare. The trail kept south of “the Big Hill,” later known as Rushing Hill and always used as a landmark.

The first white men who went to the mountains naturally followed this known pathway. The ’49ers used it. In that fairly dry year it worked well. In 1850, which was a wet season, the route became a swamp and the route now pursued by Highway 120 began to be evolved, but the Willow Springs Road continued in dry weather favor until about 1870. In early days the ranches (mentioned in order from the modern highway) were owned by Lewis Williams, Stone, Hodgdon, Dan Mann, Thorpe, Rushing and (at its junction with the road from Modesto then known as the Rock River Road) 3000 acres by Louis D. Gobin. The ruins of Gobin’s adobe house have marked the site for years. His large barn was an institution and, as soon as the hay was “fed up,” it served as a dance hall for the rest of each winter. The barn was torn down and rebuilt on the Ingall’s ranch.

Possibly six miles south of the Rushing Ranch at Big Hill, and on Rock River Road, was the “Rock River Ranch” of William F. Cooper, an officer under General Scott in the Mexican War. Cooperstown came into being along the south end of Cooper’s ranch about one-half mile from his house. It was natural that the Rock River Road from this point (even after merging with the Willow Springs Road at the Gobin Ranch) should often be termed “the Cooperstown Road.”

At first James Thorpe handled the stage station and eating place for the route in his adobe home. In 1863 William Henry Rushing, at the age of 28, bought out the business and established the famous Rushing Ranch. The Willow Springs School stood in a pasture just northwest of Rushing Hill and faithfully served the children of the far-flung community for years.

So much for the feeder roads from the south.

Considering the Sonora Road for a few miles farther, it is only necessary to say that it stayed very closely to the course of Highway 120.

At 2.7 miles from the Knight’s Ferry-bridge-road the old road to Two Mile Bar bridge turned off the Sonora Road toward the north. This was used only prior to the flood of 1862 and was known as Devil’s Flat. The land on both sides of the highway was the John Dunlap Ranch. His rock fences were five feet high. and cattle-tight.

Beyond him the A. S. Dingley Ranch spread on all sides. At 4.4 the Mark Crabtree Ranch lay to the north. It was a stopping place for teamsters until about 1900.

Jeremiah Hodgdon’s foothill ranch lay to the south of the road. A fruit stand and a small zoo have stood on the highway for many years. Hodgdon was better known for his summer ranch within the present Yosemite National Park boundaries where he took his cattle for summer grazing and maintained a stage stopping place.

At 5.7 John White’s ranch lay to the south. The land of his two bachelor brothers, Joseph and Tom was on the north. Rushing Hill is to the south, topped by a modern fire lookout.

To the right of the road was the land of “Bull John” Probst. It is now the Johnson estate and is a quail refuge. John Probst’s descendants are still in residence.

The Kessler Ranch, some miles farther on, has its name on the gate. It was originally claimed by Daniel Cloudman, a ’49er, then belonged to John Curtin, later still to the Ellinwood family and was recently purchased by Dr. Kessler of San Francisco.

The land extends for more than a mile along the road but a fine spring originally decided the location of the house. Cloudman, on his first plodding journey past the spot, was tired and ill. The spring gushing beside the trail was shaded by a young oak just large enough to afford protection from the sun. He stayed several hours and, as soon as was practical, came back and acquired the land. He and this favorite tree remained together the rest of his life. The spring has since been deepened into a well and a small windmill west of the bunkhouses stands guard over it, companioned by the old oak.

From time unknown it had been a camping place of Indians from the north who came to gather acorns or simply stopped on their way to the big powwows. Daniel Cloudman continued to make them welcome and the rift of rock south of the highway was tacitly considered their property. At that time there was a grove of large oaks near the creek across the highway. Acorns were plenty and the rocks were full of grinding holes. The Indians were Cloudman’s good friends. In fact, after the shock of impact with the rough and often ruthless miners had worn off, there was little trouble between Indians and whites for the entire length of the road to Yosemite.

That Cloudman should keep an eating place for teamsters was considered a matter of course. After all, he lived there and the teamsters had to eat. The newer and drier route leading past his house was known as the Cloudman Road from its junction with the Willow Springs Road clear to Keystone, but actually both of these roads were simply alternate routes (named for purposes of clarity and convenience) on the old Sonora Road.

It was 1879 when John Curtin, a native of Ireland, acquired the ranch and for 23 years he drove a sixteen mule team between Stockton and the Southern Mines. He was assisted by three of his sons, Michael, Robert A. and John B. Curtin. The latter seized the opportunity of long, lonely hours to study law. He carried Blackstone as unfailingly as the blacksnake and, fastening the jerk-line to the saddle of the steady “wheeler” which he rode, let the well-trained animals pick their way. At the age of twenty-two he was District Attorney and later became State Senator from the district, locally known as “Honest John.”

A post office officially termed Cloudman was opened in ’82 in John Curtin’s front room. Daniel C. Cloudman, growing older and deafer, was appointed postmaster. In ’95 the first telephone toll station in Tuolumne County was installed in the same room.

John Curtin, Jr., took over the management in 1908, adding by purchase several adjoining ranches. One especially was of interest because of the owner’s name. Jack Wade, better known as “Nigger Jack” came to the state as a slave, bought his freedom and settled down as a recluse. His 460 acres were located at the base of Table Mountain, southwest of O’Byrne’s Ferry bridge. He was respected for his honesty but was illiterate and suspicious. He lived alone to a great age in a tiny hut squarely in the middle of his property and surrounded by his cattle, hogs and chickens. On present-day maps a mountain of the vicinity bears the caption, “Nigger Jack Peak.”

The Curtins were an example of the many ranchers who passed gradually from the freighting to the cattle business, keeping their stock on the home (or foothill) ranch in the winters and pasturing them on their high mountain range in the summers.

The main dwelling now on the property was built during the Curtin regime. It is the fifth house to be used as headquarters; fire—the terror of the foothills—having destroyed the other four.

At 8.4 a clump of trees north of the road once sheltered the ranch house and teamsters’ stop operated by Captain Charles Lewis. Reputedly he was one of the many who left their ships in the harbor at San Francisco and made for the diggings. On the death of his wife he had no heart to remain. He buried her near the end of the grove; marked the grave with a pile of white quartz and left the mountains.

Across the highway to the south and over a knoll was the Hugh Mundy Ranch. His summer grazing ground for sheep in early days was Gin Flat. He sold to “French Andre.”

When almost two miles past the Kessler ranch house a small dirt thoroughfare leads south. In the words of the time-honored joke “Don’t take that one"; for about 100 yards beyond is another similar little road along which the old freight route turned away from the present highway. Both these lanes are at present labeled “Red Hill Road.” Along the course of the second one the old Sonora Road proceeded a few hundred yards, or as far as Keystone.

Keystone may be recognized by the tracks of the Sierra Railroad connecting Oakdale with Jamestown and Sonora. It was begun in 1897, completed to Angel’s Camp in 1902; gradually became dormant; was given new impetus by the Hetch Hetchy Railroad which operated as a branch of the Sierra; gradually became dormant again at the completion of the Hetch Hetchy dam project and is now used mainly for freight. Where the road crosses the tracks a queer, high-shouldered shelter, open on two sides, served as a depot. Over the arch is the word “Keystone.” This was once a prosperous crossroads settlement but was not destined to survive.

The best-known local character was Billy Fields who arrived early in the gold rush and sold liquor and a sparse selection of supplies to passing miners. Scraggly eucalyptus trees shade the rock foundations of his small store directly across the road from the depot. His house was a few yards north near Green Springs Creek.

Keystone was the setting for a good many melodramatic happenings. Robert Curtin remembers that, about 1878, some outlaws invaded the premises and when they rode away, left Billy Fields shot in wrist and breast and unconscious. They also tied young John Grohl, who had come down the Sonora Road from Green Springs for the mail, and left the two together. John managed to grip a sharp kitchen knife in his teeth and commenced sawing at the rope on Fields’ wrists. Finally he cut a strand. From that start they succeeded in freeing each other and John rode to Chinese Camp for Dr. Lampson.

In spite of such periodical excitements Billy Fields was in business a long time. It was ’92 when he finally died of a gunshot wound. He is buried at the west end of the pasture that parallels the tracks on the north. There is no marker and his grave is frequented mainly by tapping woodpeckers and an occasional rattlesnake. The Horatio Brunson family later acquired his land, added to Fields’ structures and operated a large freighter stop for many years.

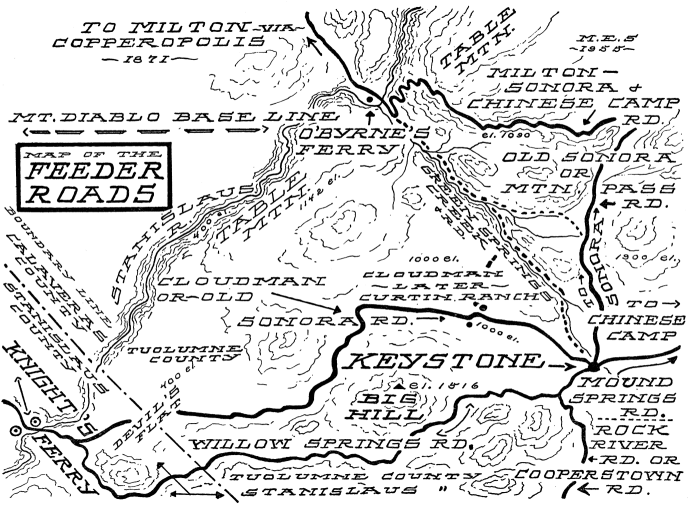

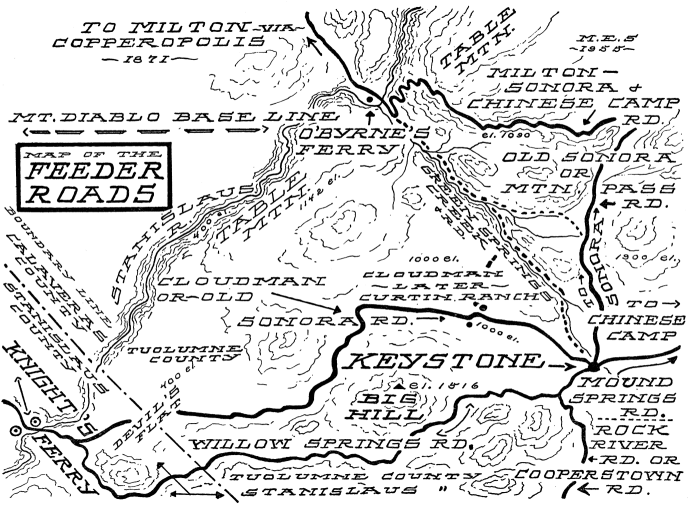

Keystone is said to have gained its name from the number of roads focussing there. In this chapter we are giving such data as we have accumulated about these feeder roads with the towns, or crossroad stores, that enlivened their otherwise lonely miles. They were important in their day but are lost to memory now except for just such small mentionings as are given here. If they are not of interest skip the next few pages. If they are, by all means use the map.

First—the combined Willow Springs and Rock River Road (often called Cooperstown Road) arrived at Keystone from the south via what is now the railroad track. From here on to within a mile of Chinese Camp the route that evolved from this old Indian trail had another name, the Mound Springs Road.

Second—the Sonora Road, which deviates from the course of Highway 120 to curve through Keystone on a detour of less than one-half mile, leaves by way of the railroad tracks, joins the highway again and makes its way more or less north, through Mountain Pass, to Jamestown and Sonora. At Keystone it ceased to be called the Cloudman Road and became the Mountain Pass Road but that eccentricity was just to make things interesting for future historians. In its entirety it was still the old Sonora Road.

The forgotten community of Green Springs stood north of the highway (Sonora Road) at .6 mile beyond the turnoff into Keystone and is noted as the locale of Bret Harte’s “Sappho of Green Springs.” There are at least two springs of which one has been cemented and is wreathed thickly in blackberry vines. In the early ’50s Thomas Edwards operated a stopping place here and the Joseph Aldridge home also dated back to mining days. The John Grohl family lived at Green Springs very early and the property still remains in their possession.

One-quarter mile west of the springs, but considered as being at the settlement, is the grave of John T. Brasefield. He is buried under a symmetrical oak tree which is often eaten off by cattle to an even distance from the ground. John Brasefield was born in 1830 and died of a gunshot wound in 1855. Further information about him seems to be non-existent. He may have been a stranger who left a waiting and wondering family somewhere in the east or he may have been well rooted in California. Possibly some reader will be able to add extra details to present knowledge of this grave.

The first orange trees in Tuolumne County were planted on the Jules and Jean Reynaud ranch to the right of the highway.

Presently Highway 120 (approximately the old Sonora Road) crosses Green Springs Creek and, a mile farther, the Milton-Chinese Camp Road leading to O’Byrne’s Ferry bridge and Copperopolis. Just beyond, on the early Beckwith ranch, stands a ruined stone structure. This was originally about ten feet high, had four embrasures facing the road and was intended for defense against Indians. The Captain Grant who commanded the militia at Knight’s Ferry in 1849 had something to do with its construction according to Robert Curtin. Old-timers have referred to it as the fort.

Yosemite Junction was known in trail days as the Goodwin ranch. J. W. Goodwin founded this stopping place in 1854 and ran it twenty-seven years. Beside the regular buildings he erected a winery of stone and adobe of which remnants remain, shaded by century-old but still prolific fig trees. The first of the two “Mountain Passes” through Table Mountain can be seen just ahead but, for the purposes of this account we may end the description of the Sonora Road at the Yosemite Junction corner.

Third—a feeder road of little importance came into Keystone from O’Byrne’s Ferry by a route passing the ranch of Ambrose De Bernardi. In fact he practically constructed it himself for convenience in reaching the foothill towns where he peddled his fruit and vegetables, wine and vinegar. This route was called the Green Springs Road because it remained close to the lower part of Green Springs Creek, a tributary of the Stanislaus River. It was used by neighboring ranchers as a shortcut. It is said that the saddle trail, which was its humble beginning, was a favorite of Joaquin Murieta and his riders on their way from Marsh’s Flat and Indian Bar (their hangouts south of Moccasin) to Shaw’s Flat and Sawmill Flat near Sonora. Privacy, to them, was more desirable than better travelling conditions. The Green Springs Road was never much used and is now practically obliterated.

Fourth—Cutting across the Mountain Pass Road (Highway 120) near Goodwin’s (Yosemite Junction) was the all-important Milton-Chinese Camp Road just mentioned. At the time of the Civil War it siphoned business from Copperopolis, then the main source of copper for the nation. After the year 1870 when the railroad was constructed from Stockton to Milton the supplies came by boat to the former, thence by railway to Milton and from there by stage or freighter to the mountain mining settlements and Yosemite. The Milton-Chinese Camp Road carried this traffic and, although it went through Goodwin’s instead of through Keystone, many of the wagons branched off to pass through the congested cross roads of the latter on their way to other places. As the vehicles reached Goodwin’s they were confronted with one of the few road signs placed in early mining days: a large slab of wood hanging from a tree depicting a pig-tailed Chinese with a pack on his back. The caption read, “Me go China Camp . . . Three mile one half.”

Milton is almost deserted now and has some interesting ruins of stone and adobe buildings. Portions of the railway depot are to be found, forgotten stores and an occasional dwelling. As the town is on the north side of the Stanislaus River the road crossed at O’Byrne’s Ferry, a small settlement that made dramatic history during its adolescence. The ferry did not last three years, for in the flood of ’52, it was swept downstream and dashed to pieces. Some form of crossing was imperative and Patrick O’Byrne commenced work on a bridge. The San Francisco Alta California ran an article on September 12, 1852, which stated: “Mr. Byrne is building a suspension bridge over the Stanislaus River at Byrne’s Ferry. It is eight feet above highwater and is made of chain cables.”

This was probably the beginning of the controversy as to whether the name of the builder was Patrick O. Byrne or Patrick O’Byrne,2 with the suitable resultant effect upon the name of the ferry and the subsequent bridge. The same publication, in its issue of January 18, 1853, speaks of the “enterprising projector and chief promoter” as Mr. P. O’Byrne. This is now considered correct. The Alta California also made the broad statement that the wire suspension bridge then under construction was “to endure for all time"—an optimism corrected in the issue for November 25th of the same year as follows: “The bridge across the Stanislaus River known as Byrne’s Ferry Bridge fell in on Wednesday in consequence of the chains parting at one end. There was on the bridge at the time a six ox-team and two men. The team was lost, but the men succeeded in making their escape. The cause of the chain breaking is thought to be the extra weight caused by the rain. It is estimated that $3000 will repair the damage.”

The bridge was repaired or rebuilt and lasted until 1862, the much vaunted flood year of exciting memory, when it went down the roaring river in company with a flume, a house and a miscellany of smaller things. It was replaced at once by a cantilever type with no center piling to annoy winter floods. The third O’Byrne’s Ferry Bridge is said by S. Griswold Morley, in his The Covered Bridges of California, to be the longest covered bridge of that particular type in the nation. It is angular and singularly ungraceful but has always carried light traffic competently although the timbers of its massive interior bracing are bent far out of line. Progress has now slated it for removal but, fortunately, it will probably be set up again in some state park as an historic memento. [Editor’s note: This bridge was destroyed by a flood behind Tulloch Dam in 1957—dea.]

On the north side of the Stanislaus at O’Byrne’s Ferry the Pardee brothers, George and Joe, operated a trading post in 1850. For years George made it his business to see that the American flag flew from the top of Table Mountain on that portion of the great plateau nearest to their little store. This is reputed to be that section of the mountains of which Bret Harte’s “Outcasts of Poker Flat” gives a picture.

Fifth—and most important to this account was the Mound Springs Road connecting Keystone with the Big Oak Flat Road which began at Chinese Camp and took the freight outfits the rest of the way to Yosemite Valley. Mound Springs Road is (excepting the Sonora Road-Highway 120) the only one leaving Keystone which is still fit to travel; it proceeds across the Sierra Railroad tracks and up the hill in plain sight. Although it served as a feeder to the Sonora Road by siphoning in the traffic from La Grange, Coulterville and other points south, it was actually a sort of detour. It diverged, only to connect again higher in the mountains after a decided swing to the south and east. Because of its many good road houses and stopping places it was more popular with the drivers than the Mountain Pass section which it by-passed. On the long slow up-haul they usually took it. Coming back empty they were apt to clatter and bounce through Mountain Pass.

The first landmark, only a few yards after crossing the tracks at Keystone, is Billy Fields’ old barn. The surrounding corral sometimes extends hospitality to six or eight of the most tremendous Hereford bulls imaginable. Apparently they remain out of sheer courtesy as no ordinary fence would prove very effective as a barrier. The substantial house now pertaining to the barn is the residence of Edward Jasper. It was built on the ranch of a descendant of Daniel Boone and was first called “the Boone House.” Mr. Jasper purchased and moved it to Keystone where he has lived in it for over fifty years but, so strong is custom in the mountains, that it is sometimes still spoken of by its first owner’s name.

Less than half a mile beyond Keystone stands Dunow’s Camp, the site of the Green Springs Schoolhouse where, in the ’70s, Maggie Fahey, started teaching at the age of sixteen with more than seventy ungraded pupils. Here gathered the children of the Walkers, the Curtins, Boones, Trumpers, Ballards, Aldridges, Stevens, Rosascos, Brunsons, Adams, Bolters and even the DeBernardis from over near O’Byrne’s Ferry—names that live in the history of the county. It took only a few families to form a large school.

Now, for over a mile Mound Springs Road runs southerly coincidentally with the new La Grange Highway. The present house of George Bolter, on this stretch, was formerly the H. N. Brunson homestead, a teamsters’ stop, and bore the sign “Travelers’ Home.” Still earlier it was known as Stevens’ Place and was operated by L. A. Stevens as a hotel in 1856. It has been enlarged but is built around the nucleus of the 100-year-old chimney and still contains much of the original furniture. The Brunsons ran the freighters’ stopping place at Keystone after Field’s death.

Two miles from Keystone the Mound Springs Road, in existence years before the highway from La Grange was thought of, twists to the left and starts up a canyon. This corner is one of the most interesting in Tuolumne County. The large meadow west of the highway was the site of the unbelievable Tong War on which the whole countryside so gaily embarked and where a couple of Chinese were killed and several wounded. The story is told in the next chapter as an inseparable part of the history of Chinese Camp, but the imaginative may possibly envision some 2000 Chinese shrilly, happily and above all noisily sparring away at each other with crude hand-made weapons until blood was shed and satisfied the honor of both sides.

In the northeast corner of the intersection, near the fig trees, Ezekiel Brown built a stopping place in 1850 and lived there at least ten years. Then John Stockel took over the property and founded the station that afterward bore the name Crimea House. It was burned in the ’70s; a fate that seemed almost inevitable sooner or later in the mountains. A new frame house was put up which did not succumb to flames until 1949. It had a combined kitchen and dining room, both to save steps and because the teamsters liked the homey atmosphere. The rest of the lower floor, outside of the family quarters, was a big clubroom for the men. The upstairs was a dormitory.

While his eight children were still small, John Stockel was bitten by an animal with rabies and died shockingly and speedily. Cyntha Stockel carried on. She put all the resources of a healthy body and an indomitable will into running Crimea House and raising her children and, even in her first days of adversity, she turned no one away but gave food and shelter to any penniless passerby. Across the road the barn and corral still stand. The corral is circular and was laid out accurately using an oak as the center. It is in good condition, with walls five feet high and two feet thick made of dry-laid rock, and shows the excellence of its patient construction by Chinese labor.

The name “Crimea House,” although known to all old residents, seemed to be difficult for them to explain. Finally the authors, with inspired lack of the faintest qualms, sent out questionnaires to anyone who might be expected to know and supplemented this source of information by personally asking everyone in sight for miles. Answers were vague. Everyone was surprised that he or she had not questioned the name before but all said that it had to do with the Chinese; the majority tied the name to the Tong War. We have come to believe that the people of the vicinity, many of them Europeans, were greatly interested in the Crimean War which was raging in 1856—the year of the Tong battle; they spoke of the latter as the local Crimean War and the name stuck to the property as nicknames sometimes do. The late Mrs. Frank Dolling of La Grange, granddaughter of John and Cyntha Stockel, agreed readily that this was the most likely explanation.

We were somewhat confirmed in this supposition by later finding a statement in the Memoirs of Lemuel McKeeby telling of another locality named in just such haphazard fashion by reason of the Crimean conflict: “The little town of Sebastapol,” he wrote, “was close by the diggings. It was composed of three houses at that time. . . . The Crimean War was then in progress and as two Englishmen —brothers—who had put up a saw mill in that settlement, were eternally talking of Sebastapol, we miners gave that name to the place.”

In such casual manner the pioneers bestowed many of our California place names.

The mountains close in beyond Crimea House. Somewhere near Stockel’s roadhouse the trail veered to the right and around a hill called in succession Red Mountain, Mount Pleasant or Taylor Mountain. The Taylor Mountain route was not successful because a little creek, soon to be known as Six Bit Gulch, was turbulent in the wet season and had a difficult crossing. It seems probable that the Indians, who traveled mainly in the summer, chose well-watered trails with little regard for their condition in winter. By 1850 the miners had abandoned their course around Taylor Mountain and were traveling the Mound Springs route as it is today. Evidently, in looking for a better crossing of the creek the present road was evolved. So we find that, after 1850, the Mound Springs Road passed what was later Crimea House corner, between the house and the corral; climbed Crimea Hill and proceeded along a brush-filled wash.

The springs for which the road is named flow from a series of spongy tussocks or mounds of sod covered with swamp grass. They are found in a meadow to the right and are the source of a swift gurgling stream. The lavishly watered meadow was, in the days of the cattle kings, a welcome stopover for the herds on the way to and from summer pasturage in the high mountains.

The first proprietor of the Mound Springs Ranch was John Flax who lived and died there and is buried in the flat area just beyond the present dwelling. At that time most of the property was a large vineyard, and his grave was under the vines.

Beyond the springs is abrasive country—full of sharp rocks, stickery weeds and digger pines. It is also full of turkeys who do well in the 1000 to 2000 foot level. Turkey raising seemed at first to be a sublimation of the tendency of the region to propagate grasshoppers. Not since the Indians counted them a dietary luxury had these excitable insects been so popular. Now the industry is so standardized that the pampered birds, raised within fences, never see a hopper. The road, winding north of Mount Pleasant, comes to Six Bit Gulch about where the smaller Picayune Gulch empties into it. Both names were given in derision because of the poor diggings in their neighborhood. On these gulches lived, in peculiar mud huts, a few Chinese of different habits and appearance from those of Chinese Camp. They were generally known by the townspeople as “Tartars” and never mixed with the other Orientals. One hut survived until recently and may still be there.

Six Bit Gulch was a welcome sight in early autumn as a the cattlemen drove the herds back from the high mountains. It was the first convenient watering place west of Jacksonville. It was not so welcome in the spring when they made the upward journey, being in those days a deep and turbulent stream in which, at various times, riders were drowned. Remembering this, its present inocuous condition requires explanation. Adjoining ranchers tell us that the creek changed completely after the section around Montezuma was dredged. It is possible that the drainage slope was altered in some way or the water supply tapped. The long dry cycle just ending, no doubt, had something to do with it also.

Beyond the gulch, which now is not even dignified with a bridge, stood the establishment of John Taylor and his wife, Margaret. The house was on the left immediately beyond the ford, between the gulch and the road as it turns and leads north toward Montezuma. Directly across the road was the large barn. The corrals were between and were so arranged that the road passed through them, necessitating the opening and closing of two gates. This was primarily for the convenience of the cattlemen who broke their drive at this point. Taylor’s stage and freighter stop was founded after he had failed in the diggings. He did not maintain a regular dining room but, of course, any hungry man was welcome to come in and eat. Taylor was Justice of the Peace and, although hospitable, he was also practical. This story of early-day court practices came our way: A jury case was slated to be held at Taylor’s Ranch. The court was assembled at the old house in Six Bit Gulch. The attorney for the prosecution, a Sonora lawyer who liked his liquor, discovered upon investigation that there was no great amount of that commodity on hand. He rose and requested the judge for a change of venue to Jamestown. Judge Taylor, deciding that if one of the two must be discommoded it might as well be the lawyer and not he, slapped his hand resoundingly on the table and announced firmly, “I’ve just bought a two dollar roast to feed the jury. Change denied.”

At Taylor’s the traffic for Big Oak Flat and Yosemite Valley left the Mound Springs Road which continued northward with Six Bit Gulch. Possibly a mile along the course of the latter is the ranch of Robert Sims, in the same family since pioneer days. Farther is the historical marker telling of the settlement of Montezuma which, in 1849, possesesd rich placer mines. A trading post was established there in that year by R. K. Aurand and Sol Miller and was shortly followed by a teamsters’ stop and stage station, under the same ownership, known as Montezuma House.

And so, having used the Mound Springs Road from Keystone to Six Bit Gulch, the wagons bound for the Big Oak Flat Road and Yosemite said goodbye to it at Taylor’s and turned uphill to the northeast.

The one-mile-long stretch connecting Taylor’s with the next town goes through scrub-grown, broken country, beautiful only in spring. It surmounts the hill at an open level filled with yellow tar weed across which is a vista of but medium allure—the outskirts of Chinese Camp.

When the first white men saw this mountain flat it was filled with a stupendous growth of glorious oak trees. In a few months it was a waste of dismal stumps which took much longer to disappear. Now it is a mixture of gravel and red earth, baked in summer but capable of bottomless mud, to which of late years has been added some regrettable landscaping in the form of dumps.

Before the day of black-top surfacing this last half-mile was anathema to the impatient and hungry driver. He might spend hours extricating his wagon and trailer from one sink hole after another while the friendly buildings of what was then a large town stood tantalizingly close and in plain sight across the adhesive waste.

Next: Chinese Camp • Contents • Previous: Knight’s Ferry

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/big_oak_flat_road/feeder_roads.html