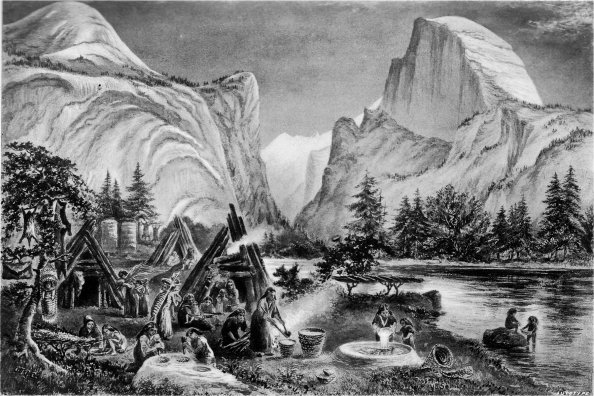

NORTH & SOUTH DOMES.

[click to enlarge]

[Color reproduction of this painting (did not appear not in book).]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Granite Crags > Chapter 7 >

Next: Chapter 8 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 6

A COTTAGE HOTEL—THE VILLAGE—YOUNG STUDENTS—THE CASCADES—DIGGER INDIAN CAMP—PRIMITIVE MAN—ACORN-FLOUR—EDIBLE PINES—INDIAN AGENCIES—THE MODOC WAR.

Barnard’s Hotel, 8th May.

Our naval friend and the Cashmerian sportsman having been obliged to return to the low country, we have carried out our original intention, and forsaking the Union-Jack for the Stars and Stripes, have established ourselves at this pleasant little wooden bungalow, about a mile farther up the valley, and on the river—a beautiful situation. This was the site of the old original house, built by Mr Hutchings—one of the first white men who set foot in the valley, and who published accounts of it and opened it up to the world. Entranced with its beauty, he brought a lovely young wife to settle here, and his were the first white children born in the valley.1

[1Strange to tell, when in after-years Florence, the first-born—a bright, joyous girl—returned to the valley on a visit to her friend Effie Barnard in the autumn of 1881, the Angel of Death took both these happy young lives within a few days of one another—the first-fruits gathered by the Great Reaper in this secluded harvest-field. So the two girls lie side by side beneath the old oaks in the valley, so dear to both; and the sighing winds, and the murmuring waterfalls, and the twilight calls of the turtledoves, sing their requiems for evermore.]

All arrangements here are of the simplest—quite comfortable, but nothing fine. The main bungalow, which is surrounded by a wide verandah, has on the ground-floor a minute post-office, booking-office, and bar; a large diningroom, with a row of windows on each side, occupies almost the entire space, and opens at the farther end into a clean tidy kitchen, where a Chinese cook attends to our comfort.

An outside staircase leads to another wide verandah running round the upper storey, which consists entirely of bedrooms. A separate wooden house stands just beyond it—also two-storeyed—and all divided into minute sleeping-rooms. I have chosen one of these, as it commands a splendid view of the falls; and from the earliest dawn I can watch their dream-like loveliness in every changing effect of light—sunshine and storm alike minister to their beauty.

It must be confessed that the rooms are rough-and-ready; and the partitions apparently consist of sheets of brown paper, so that every word spoken in one room is heard in all the others! I am so well accustomed to this peculiarity from long residence in the tropics (where ventilation is secured by only running partitions to within a foot of the ceiling), that it does not trouble me much, but must be somewhat startling to the unaccustomed ear which finds itself unwillingly compelled to share the varied conversation of the inmates of neighbouring stalls! I confess that last night I was forcibly reminded of the story of the man who snored so loud that he couldn’t get to sleep, so had to rise and go into another room that he mightn’t hear himself!

On the opposite side of the road is the Big Tree Room, which is the public sitting-room, and takes its name from a quaint conceit—namely, that rather than fell a fine large cedar which stood in the way of the house, Mr Hutchings built so as to enclose it, and its great red stem now occupies a large corner of the room! Of course it is considered a very great curiosity, and all new-comers examine it with as much interest and care as if it were something quite different from all its brethren in the outer air! It certainly is rather an odd inmate for a house, though not, as its name might suggest, a Sequoia gigantea.

It stands near the great open fireplace, where, in the still somewhat chilly evenings, we gather round a cheery fire of pitch-pine logs, which crackle and fizz and splutter, as the resinous pine-knots blaze up, throwing off showers of merry red sparks. It is a real old-fashioned fireplace, with stout andirons such as we see in old English halls. Round such a log-fire, and in such surroundings, all stiffness seems to melt away; and the various wanderers who have spent the day exploring scenes of beauty and wonder, grow quite sympathetic as they exchange notes of the marvels they have beheld.

Beyond the Big Tree Room, half hidden among huge mossy boulders and tall pines, stands a charming little cottage, which is generally assigned to any family or party likely to remain some time.

At a little distance, nestling among rocks or overshadowed by big oaks, lies a small village of little shanties and stores (alias shops),—a store where you can buy dry goods and clothing on a moderate scale—a blacksmith’s forge—a shop where a neat-handed German sells beautifully finished specimens of Californian woodwork of his own manufacture, and walking-sticks made of the rich claret-coloured manganita. Then there are cottages for the guides and horsekeepers, and an office for Wells Fargo’s invaluable Express Company, which delivers parcels all over America (I believe I may say all over the world). There is even a telegraph office, which, I confess, I view with small affection. It seems so incongruous to have messages from the bustling outer world flashed into the heart of the great solemn Sierras.

As a matter of course, this glorious scenery attracts sundry photographers. The great Mr Watkins, whose beautiful work first proved to the world that no word-painting could approach the reality of its loveliness, is here with a large photographic waggon. But a minor star has set up a tiny studio, where he offers to immortalise all visitors by posing them as the foreground of the Great Falls!

And last, but certainly not least, are Mr Haye’s baths for ladies and for gentlemen, got up regardless of expense, in the most luxurious style. The attractions of the baths are greatly enhanced by the excellence of the iced drinks compounded at the bar of such a bright, pleasant-looking billiard-room, that I do not much wonder that the tired men (who, in the dining-room, appear in the light of strict teetotallers, as seems to be the custom at Californian tables d’hôte) do find strength left for evening billiards! with a running accompaniment of “brandy-cocktails,” “gin-slings,” “barber’s poles,” “eye-openers,” “mint-julep,” “Sampson with the hair on,” “corpse-revivers,” “rattlesnakes,” and other potent combinations.

Mr Haye’s special joy and pride is in a certain Grand Register, in which all visitors to the valley are expected to inscribe their names. It is a huge, ponderous book, about a foot thick, morocco-bound, and mounted and clasped with silver. It is said to have cost 800 dollars. It is divided into portions for every State in the Union, and for every country in the world beyond; so that each man, woman, and child may sign in his own locality, and so record the fact of his visit, for the enlightenment of his own countrymen.

The entries include names from every corner of the earth. Already the stream of visitors is setting in, and a few days hence all the hotels expect to be well filled for their short season of about three months, during which many Californians take their annual holiday. After that, though the autumn is glorious, only a few real travellers find their way here.

Considering that people in these parts must be pretty well accustomed to every variety of nation and of raiment, I am much amused by the amount of attention bestowed on Mr David’s apparel, which is simply that of the ordinary British sportsman—a sensible tweed suit. The day we left San Francisco, we were “riding in a tram-car,” when a man got in, and straightway his eyes were riveted, first by the stout-ribbed woollen stockings, woven by a fine “canty” old wife in the north of Scotland, and then by the strong British shooting-boots, with their goodly array of large nails. Not a word did he utter till he was in the act of leaving the car, when he could refrain no longer, but slowly and emphatically remarked, “Well, sir, I guess I’d rather not get a kick from your boots!”

This morning a small boy, seeing me sketching near the school, came up to inspect us. After a leisurely survey of Mr David’s garb, he solemnly—apparently not with cheeky intention—remarked, “I say, mister, are not your pants rather short?” Evidently knickerbockers were a new revelation to his youthful mind—accustomed only to see full-length trousers stuffed into high jack-boots.

The small boy was laden with school-books, one of which was a very large volume of American history. As each State already furnishes a separate section as large as an average school-history of any country in Europe, it follows that the complete work must be the size of an encyclopedia; and I felt considerable pity for the unlucky rising generation who have so large a dish to digest. However, they are apparently not much troubled by the ancient or modern history of other countries.

Our little friend, having been joined by several sisters (clustered on a tall horse, and all laden with school-books), the family party volunteered to favour us with some choral hymns. If not strictly musical, the effort was kindly and characteristic. This done, all climbed on to the tall horse, and, crossing the river at the ford, went on their way rejoicing.

Among the early arrivals in the valley are two very pleasant Englishmen, who have just been doing a very interesting riding tour in Mexico. They prove to be “friend’s friends;” and to-day we joined forces on an expedition for some miles down the beautiul river (which flows so calmly and peacefully through these quiet meadows), to the spot where it begins a rapid descent, chafing and wrestling with great boulders, rushing headlong on its downward way, raging and roaring—a tumultuous chaos of foaming waters. These rapids extend for a considerable distance, passing by beautiful groups of old pines and other noble timber, and, in fact, are the feature of the expedition.

But our actual destination was a lovely little fall known as “The Cascade,” where a minor stream comes leaping over the cliffs in a succession of broken falls, flashing in and out among the beautifully wooded crags, till, with one joyous bound, it lands in a small secluded meadow, across which it glides in a clear sparkling stream.

Here we unpacked the luncheon-basket, which had been slung on to one of the ponies, and, with the flower-sprinkled turf for a table-cloth, and a cloudless blue heaven overhead, we concluded that our mutton

|

|

| Photo-Engraved by | T&R Annan |

|

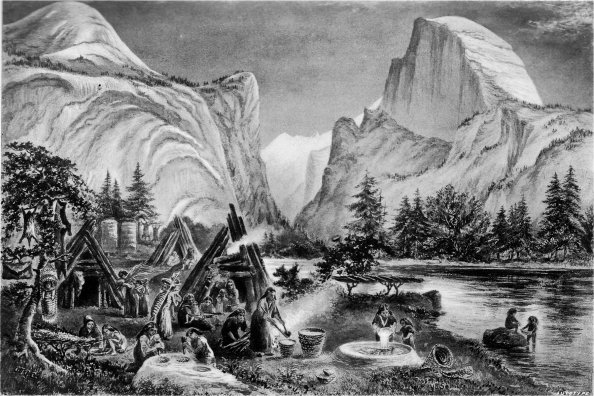

INDIAN CAMP BESIDE THE MERCED RIVER.

NORTH & SOUTH DOMES. [click to enlarge] [Color reproduction of this painting (did not appear not in book).] |

|

Thursday, 9th.

I have been all day sketching a most picturesque, but unspeakably filthy, Indian camp, of conical bark-huts. It is pitched about a mile from here, on a lovely quiet reach of the river, sheltered by grand old trees, and with the mighty Domes towering overhead. If beautiful clean Nature could preach her own lessons, she might surely do so here; but a dirtier and more degraded-looking race than these wretched Digger Indians I have rarely seen—nowhere, in fact, except in Australia, whose aboriginal blacks are, I think, entitled to the very lowest place.

These Digger Indians are a small race; their tallest men do not seem up to the standard of average whites. All have a thick mop of the most unkempt, long, lanky black hair. The men sometimes wear long braids; the squaws cut theirs across the forehead, in a fashionable fringe. They have square, flat faces, with mouths opening from ear to ear like night-jars. Some of the men embellish their faces with streaks of vermilion; but where, oh where! are the ideal war-paint and feathers? Most of them wear dirty tattered old woollen clothes, probably cast off by campers, and eked out with a certain amount of peltry, filthy beyond description. Some, however, are dressed in suits of half-tanned leather, embroidered with beads, and a few dandies have Spanish-looking felt hats, and bright-coloured handkerchiefs thrown over their shoulders. These are the wealthier members of the community, and ride about on small ponies, the squaws riding “straddle-legs” (i.e., astride). Rope-halters fastened round the lower jaw act as efficient bridles.

Some of my friends had the good fortune to witness a Digger Indian festival, when about a hundred of these strange beings assembled for a solemn dance. They formed in a large ring, and moved slowly round and round, with a jiggy springing step. There did not seem to be any characteristic feature in the dance, and certainly no grace. The dancers, however, seemed thoroughly to enjoy themselves, and it appears that this is a favourite evening amusement. One solitary mortal may begin jigging all by himself, to the music of his own howls, and straightway others catch the infection, and set to dancing each by himself, and so continue for hours.

I am told that some of the tribes periodically hold great religious “medicine dances,” which are danced by chosen warriors, for the good of the whole tribe, and kept up for three days and nights without one moment’s intermission for any purpose whatever, and not a morsel of food, nor one drop of water, is allowed to pass the lips of the men selected for this ordeal. It is a feat of endurance which is never required of any warrior more than once in his life, and few are able to endure to the end of the dance. Some, indeed, endure to the death; but for a dancer to die is esteemed terribly “bad medicine,” an augury of disaster for the tribe. It is, however, quite common for men to fall fainting from exhaustion, and be carried out of the medicine-lodge insensible.

The word “medicine,” as here used, has reference to divination, by which all details of daily life are regulated. The movements of a rattlesnake, the flight of a bird, the cry of a wild beast, are interpreted as heralding good or bad luck, and are recognised as good or bad medicine. No Indian will start on a journey or a hunting expedition, without first “making medicine.” He takes certain bones of divers reptiles, birds, or animals, the ashes of some lucky plants, and portions of coloured sand or earth; these and many other unkown ingredients are stirred together in a flat vessel, and from the manner in which they blend, the Indians read woe or success in the enterprise. If the former, he carries the bad medicine outside the camp and buries it, lest any one should touch it. If it is good, he makes up little packets of it in pouches of dressed deer-skin—precious amulets—to be worn by men, women, and children. When all the pouches have been filled, what remains of the mixture is burned on the domestic hearth.

As yet I have not found any of these Digger Indians who can speak a word of English.

They carry their babies slung over their shoulders, in wicker cradles, the whole weight being supported by a strap passed across the maternal forehead. What headaches this suggests! The cradles consist only of a flat back of basket-work, with a flap down each side, and a projecting hood shaped like that of a perambulator, to shield the head of the little papoose from the sun, and also to protect it from possible tumbles. The fat little reddish-brown baby is laid naked on its basket, with a soft covering of easily changed moss spread as mattress and blanket: perhaps a small shawl is laid over the moss. The baby’s arms are tucked down by its sides, and the flaps are tied or laced across the front. Sometimes the arms are allowed to hang loose, but this is exceptional.

The creatures look just like mummies (the outer mummy-case!), and gaze forth at the world with dark eyes, as solemn and unresponsive as if they already realised their heritage of woe. Their long black hair and flat faces add to their unbabyish appearance, and altogether they are queer little mortals.

When the mothers are busy, the papoose in its cradle is suspended, like some odd parcel, from the branch of a tree, beside the drying bear-skins. There it hangs safe out of harm’s way—especially out of reach of the inquisitive dogs, who are always prowling silently about. One of these sneaked up to me to-day, and on my rashly giving it a biscuit, it made a dash at my packet of sandwiches, and scampered off rejoicing, with this dainty bite.

The wigwams are of the very rudest description, consisting only of long strips of thick pine-bark, piled up like a pyramid, and with flaps of deer-skin to curtain the door at night, and various old skins pegged down over the bark to keep out the wind. Of rain at this season there is little fear. A fire is kindled in the middle of this barktent, and the blue smoke escapes by a hole at the top, contrasting charmingly with the rich sienna and brown tones of the bark.

The filth of the surroundings is such that I have never ventured to peep inside one of these picturesque but most univiting homes, though we have visited several little encampments, and have watched hideous old crones weaving the most beautiful baskets, and smoking like chimneys—the ideal of bliss! The poetic Indian calumet of old stories is unfortunately replaced by the invariable clay pipe—dear alike to men and women!

To-day, while I was sketching the camp, several of the men had thrown their scarlet Government blankets round them, and I blessed them for the bit of colour. They were gambling with exceedingly dirty old cards, which seems to be their only occupation when not engaged in foraging.

They are very successful fishers, and generally camp near some clear trout-stream. The hotels secure a ready market for all they bring, and these Merced trout are certainly most delicious. As these are almost their only marketable property, I fear they cannot often enjoy them themselves—indeed they consider all fish insipid, and only eat it when they have nothing else. Their fishing-tackle does not involve much outlay. A light hazel-rod cut from the bank, a casting-line, and a few green grasshoppers or worms as bait, are all they need to beguile the bonnie trout. The worms are occasionally carried in their mouths as the simplest and safest method of conveyance!

They are too abjectly poor to be dainty feeders, and, as their name implies, they live partly by digging up edible wild roots, with an occasional broiled snake, frog, or lizard, or a handful of roast grasshoppers as a relish; sometimes they are reduced to eating carrion-birds, but are said to have a prejudice against magpies and wild turkeys, the latter from a belief that eating their flesh will make them cowardly.

Now and then they organise hunting expeditions, and go off in search of bears or deer; and great is the joy of women and children when they chance to be, if not in at the death, at least sufficiently near to claim their share at the “gralloching” (as we say in the Highlands), which here becomes a loathsome festival, at which all contend for a drink of warm blood, and for favourite portions of the intestines. Heart, liver, lungs, stomach, entrails—all are eagerly snatched, and, all raw and bleeding, are swallowed with the utmost enjoyment. Happy, indeed, is the maiden whose lover secures for her two or three yards of entrails (the Indian equivalent for the Parisian bonbonnière); scarcely can she spare a moment to go through the pretence of cleaning—then the hideous coil disappears down the omnivorous throat.

When all that we term offal has been thus consumed, the prize is triumphantly carried into camp. Strips of meat and of fat are hung up to dry for winter use, and the skins are prepared for clothing or for sale. I saw several skins hanging about the trees in camp this morning, and we hear that there are some bears in the neighbourhood now, but we are not likely to have the luck of seeing them.

As a substitute for the too expensive luxury of wheat-flour, these poor creatures manufacture a sort of coarse acorn flour or meal; and very bitter bread must be the result. As soon as the acorns are ripe, they set to work systematically to harvest them, ere the woodpeckers, squirrels, and mice can do so. They construct very tall cylindrical wicker-baskets, covered all over with a thick thatch of oak or fir twigs. These are called cachets (which, I suppose, means a hiding-place, though whether the word was of foreign derivation or purely Indian, I cannot say). But wherever a cluster of bark-wigwams have been erected, there invariably are several of these tall baskets, like most attenuated corn-stacks.

These are the storehouses—the granaries of these frugal beings. When at leisure, they crack the acorns, and pick out the kernels, ready for use. When required, they pound them with a smooth water-worn stone on a flat granite slab; and near every favourite camping-ground, there are generally some such slabs, deeply indented with cup-marks, very much the same as some of those which puzzle our learned antiquaries, and which may possibly be nothing more than traces of a time when our own ancestors pounded the acorns of British oaks, and made bitter porridge like that of these poor Indians.

To-day I watched the whole process of manufacture, which is primitive to a degree, and seemed like a glimpse of domestic life in the stone age. No trace of iron was there—not even a cooking-pot. The girls having prepared their acorn-meal in the rock cups (the meal being largely mingled with granite dust), they left it to steep in cold water, to get rid of some of the bitterness, while they were building up a huge pie-dish or basin of river-sand. This they lined with fine gravel, and placed the powdered acorns in this rude dish. Meanwhile others had filled their water-tight baskets—which are a triumph of art, so closely woven that not a drop of water can escape.

But how were they to boil the water for their cooking? That difficulty also was simply overcome. A large fire had been kindled, and a number of stones the size of your fist thrown in to bake. When they were thoroughly heated they were lifted out by a woman, holding two sticks in lieu of a pair of tongs, and were dropped into a small basket of water, which hissed and spluttered, and became black and sooty. After this preliminary washing, the hot stones were fished out and deposited in the large water-basket which acted the part of kettle. Though somewhat cooled by this double process, the stones soon heated the water to a certain extent.

A very small quantity of this tepid, singed fluid was then poured on the acorn-flour, some of which was made into paste and taken out to be baked as cakes. More water was added. A green fern-leaf was laid over the flour, apparently to enable the pouring to be done more gently—and so a large mess of porridge was prepared, and ladled out in baskets. Then—that nothing might be wasted—the gravel was taken out and washed, to save the flour still adhering to it.

This acorn-paste becomes glutinous, and is eaten in the same way that the Pacific Islanders eat poi, by dipping in a finger, twirling it round, and so landing it in the mouth.

The oak and pine forests yield the principal food-supply of these children of the Sierras. The commonest nut-bearing pine (Pinus Sabiniana, commonly called the Digger-Pine) grows only on the lower hills, at an altitude of from 500 to 4000 feet above the sea. It seems to require great heat. We saw a good many on our way to Mariposa.

At first sight you would scarcely recognise it as being a pine-tree, so different is its growth from the ordinary stiffness of the family. Instead of all branches diverging from one straight main stem, perhaps 200 feet high, this little pine only attains a height of about 50 feet—the stem having at the base a diameter of from two to three feet. It shoots upright for about twelve or fifteen feet, and then divides into half-a-dozen branches, which grow in a loose irregular manner—generally, but not invariably, with an upward tendency.

From thence droop the secondary boughs, with pendent tassels of very long greenish-grey needles: they are often a foot in length, and form the lightest, airiest of foliage, casting little or no shade.

From each bunch of needles hangs a cluster of beautiful cones, which in autumn are of a rich chocolate colour. They grow to a length of about eight inches, and are thick in proportion. Both squirrels and bears climb the highest branches in search of these, well knowing what dainty morsels lie hidden within the armour-plated exterior of strong hooked scales. By diligent nibbling, even the little squirrels manage to extract the nuts; but the Indians simplify this labour by the use of fire.

They climb the trees, and beat off the cones, or (more reckless than the bears) chop off the boughs with their hatchets. Then, collecting the cones, they roast them in the wood-ashes, till the protecting scales burst open, when they can pick out the nuts at their leisure, and crack their hard inner shells as they lie round their camp-fires at night, or bask idly in the sunlight through the long summer day. It is dirty work, owing to the sticky resin which oozes freely from the cones and branches, and adheres tenaciously to clothes and hands; nor is the cleanliness of the camp improved by every man, woman, and child handling the charred and blackened nuts.

But when it comes to a question of cleanliness, perhaps a little charcoal would be rather an improvement in an Indian camp!

Another tree which is valuable to the Indians as an item of food, is the Pinus Fremontiana, a stumpy little pine, rarely exceeding twenty feet in height, or forming a stem more than one foot in diameter. Its crooked, irregular branches bear a very large crop of small cones, about two inches long, each containing several edible kernels about the size of hazel-nuts, and pleasant to the taste. They are exceedingly nutritious, and are so abundant in certain districts that a diligent picker can gather about forty bushels in a season. Consequently it is a really valuable tree, and the Indians justly regard it as the food provided by the Great Father for their special use; and many a story of bloody revenge taken by the red men against the aggressive whites has been traced to the wanton destruction of these food-producing trees by the lumberers and settlers.

This Nut-pine, like the Digger-pine, keeps its succulent kernels so securely embedded in their hard outer case, that it requires the action of fire to force open the scales within which they lie concealed. It is found chiefly on the eastern foot-ranges of the Sierras, in the districts where the Carson river and Mono Indians still dwell, and does not seem to require so much heat as the Sabiniana, as it bears fruit abundantly at an altitude of 8000 feet, whereas its larger kinsman is rarely, if ever, found higher than 4000 feet above the sea-level.

This Indian gipsy camp naturally forms a fruitful topic of conversation, and leads to many animated discussions between those men who consider all Indians “a race of scoundrels—a nation who must be obliterated from the earth!” and others who see in them a race unjustly despoiled of their heritage, and whose degradation has been certainly not lessened by the invasion of the whites.

I hear many statements made, and not denied, greatly to the discredit of the Indian Agency, which is described as the most unrighteous of the many corrupt official bodies. And it is through their hands that the Government “charity” is now doled out to the tribes whom the white man has pauperised.

It was stated, not long ago, that out of 35,000 dollars a-year, voted for compensation to the Indians, not more than twenty per cent ever reached them, but in the majority of cases five per cent was a fair estimate. The rest either adhered to the hands of the agents, or was squandered by their mismanagement. And it is a well-known fact that the little that does reach the Indians does so in the form of spoilt flour, shoddy cloth, indifferent blankets, and firearms, the latter only too good, considering how often their game is human. Moreover, notwithstanding Government prohibition, they are much encouraged to purchase from the white dealers a true fire-water with large admixture of vitriol—a poor exchange for their happy hunting-grounds, where the pale-faces are now reaping their golden harvests.

Among the gentlemen most keenly interested in all Indian questions there is one who happened to be visiting the Lava-beds soon after the Modoc war of extermination, and his details of that sad story are most distressing.

He went all over the ground which was the scene of the last struggle, his object being to trace the Sacramento river to its source amid the glaciers of Mount Shasta—that magnificent peak, whose summit is crowned with eternal snows, while round its base hot sulphur and soda springs tell of still dormant fires.

Small extinct craters cluster round the broad base of the giant cone, and have doubtless done their part in the formation of the Lava-beds, which formed the last stronghold of the Modoc Indians. They extend along the margin of the Great Tulé, or Reed Lake, so called because of its sedgy shores. It is one of a group of large lakes—Clear Lake, Klamath Lake, and Goose Lake—lying 6000 feet above the sea. The ground around is white with alkali, and only stunted cedars and uninviting sage-bush can exist.

When white men saw and coveted the fertile lands in the Sacramento Valley, the red men were driven back farther and farther into the mountains. Their hunting-grounds were taken possession of, and they themselves compelled to retreat to the grounds “reserved” for them (grounds too poor for white men to grudge to the proprietors of the soil), where the wretched sage-bush is shunned by the deer, and even the streams are without fish.

Driven back ever farther and farther, the wretched Modocs at last reached “the reservation lands,” lying east of the Great Klamath Lake—a country so arid that they could not support life. So they ate their horses, and then, driven to desperation, returned to their old haunts near Lake Tulé, resolved thence to make one last effort to recover their lands or die in the attempt.

Thereupon followed the Modoc war. In old days, white men had made a pastime of shooting Indians as they would vermin; and there were some who openly boasted of having shot a hundred or more to their own gun as their season’s sport. But this was when the Indians only possessed bows and arrows. Now they had pistols and good breech-loading rifles, which they had captured in various raids—moreover, they were first-rate marksmen; so the case was different, and though there were but a handful of Modocs, numbering about forty-five armed men, the whites failed to dislodge them.

The first attempt was made in November 1872, by a body of thirty-five cavalry, eight of whom fell before the fire of an invisible foe, and the rest wisely retreated.

The Modocs then proceeded to intrench themselves in the Lava-beds, taking with them their squaws and their little ones. The Lava-beds are described as being like a gigantic sponge, fossilised to the hardest rock—full of caverns and craters, with long cracks and fissures; in short, a place in which thousands of men could safely lie concealed, and where a handful of well-armed men might defy an army.

Here they were attacked on the 17th January by a force of 450 Government troops, who had not realised the strength of the position, and were forced to retire with a loss of twenty-nine wounded and ten killed.

Matters now looked serious. It was allowed by Government that the Modocs had some cause for complaint, and a Peace Commission, headed by General Canby and Dr Thomas, was appointed to inquire into their grievances, and endeavour to put matters on a better footing. General Canby was a man of large experience—a just man, and one truly desirous to see these tribes fairly dealt by.

The Modoc chiefs were accordingly invited to attend a conference in the American camp; but vividly remembering deeds of treachery in the past, they refused to come. Finally, they agreed to meet the Peace Commissioners half-way between the camp and the Lava-beds, and hold a big talk, though each side mistrusted the other. All were supposed to attend unarmed; but in the course of the discussion, “Captain Jack,” the Modoc chief, suddenly drew his revolver and shot General Canby through the head. At the same moment Dr Thomas was shot and fell dead, and a third white man was wounded.

Then the Modocs retreated to their stronghold.

At the same moment another party had advanced to the second American camp with a flag of truce, asking to see the officer in command. This was refused, whereupon they shot the officer who had come to parley. Doubtless they supposed that they had slain their principal foes, little knowing that by their deed of foul treachery they had actually murdered two of their very best friends. It seems always to be the ill-luck of savage races to revenge the misdeeds done by bad men on the very friends who are most anxious to help them.

In the present instance, the Indians practised exact retaliation for the cruel treachery with which they themselves had been treated some years previously, when a volunteer American force, commanded by a man called Ben Wright, attacked the Modocs in these same Lava-beds and was twice defeated. Wright therefore proposed to the Indians that they should come to a big dinner and talk over their disagreements, planning to poison his guests with strychnine. Happily they did not come, but agreed to a big talk, when, at a preconcerted signal, Wright drew his revolver—an example followed by all his men. A general massacre ensued. About forty Indians were shot, and Wright was lauded as a hero.

But some of the Indians escaped, and after biding their time, contrived to murder Wright while he slept.

The Indians were hanged, but gloried in having obtained vengeance on the murderer of their people. There is little doubt that the same motive prompted the later crime, and that the tribe felt they were carrying out a just revenge in thus repeating the deed of treachery.

Very different was the view taken by the white men. Whatever grain of sympathy had previously existed was now wholly extinguished, and a howl for the utter extermination of the tribe arose from every corner of the States. The one thought was for vengeance, and a bloodthirsty craving to shoot Modocs seemed to take possession of all the whites in the country. Henceforth it was war to the bitter end. The general order issued to the troops contains these words: “Let no Modoc in future ever be able to boast that his ancestors killed General Canby.”

The Indians now seemed inspired with the energy of despair. They fortified their natural stronghold till it seemed impregnable. Six hundred troops—infantry, cavalry, and artillery—with two howitzers and four small mortars, besieged the Lava-beds for several months without result. Repeated attempts were made to carry the place by assault, but in each case the assailants had to retreat before the fire of an invisible foe.

The Indians, like other races of the Pacific, fight almost naked, and their dark-reddish skin could scarcely be distinguished from the lava around them. They have other peculiarities in common with the Pacific Islanders, as, for instance, the advance of an orator, who (in this case carefully concealed) shouted taunts and defiance to the besiegers; and also that the squaws are present during the fighting, to encourage the warriors and tend the wounded.

At length the Indians were dislodged from their stronghold by well-directed shells, which were a new experience, and took them by surprise. They still, however, found covert among the rocks, and a few days later dealt a terrible surprise to a scouting-party which had gone forth to try and track them. Seeing no sign of the Indians, the party prepared to return to camp, but first halted for a few moments’ rest and food, little dreaming that the Indian rifles even then covered them. A moment more, and out of the party of sixty, seventeen lay dead, twelve were wounded, and when the survivors returned to camp, five were missing.

It seemed as if the red men were at least to retain possession of the red rocks,—and so they doubtless would have done, had not traitors finally yielded to bribery, and betrayed their brethren. They showed the pale-faces the water-springs which enabled their comrades to hold out, and these having been cut off, the handful of survivors were compelled to surrender to the all-powerful conqueror, Thirst. Fifteen men and thirty-five women were all that remained to march out. They were bound hand and foot, and placed in waggons to be carried prisoners to Fort Klamath.

On their way they were met by a company of the volunteers from Oregon, who had so long been kept at bay by these poor desperate Indians. The Oregon white men stopped one of the waggons, cut the traces, and in cold blood shot four Indians who sat there handcuffed and helpless.

The chief and his few remaining followers were tried by a military commission, and hanged. Thus the white race have “improved” the Modocs off the face of the earth.

Next: Chapter 8 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 6

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/granite_crags/chapter_7.html