| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Yo Semite Valley >

Next: Chapter 24 • Index • Previous: Chapter 22

|

Who doth not feel, until his failing sight

Faints into dimness with its own delight, His changing cheek, his sinking heart confess The might, the majesty of loveliness?

—Byron’s

Bride of Abydos, Canto I.

|

|

How massively doth awful Nature pile

The living rock.

—Thomas Doubleday’s

Literary Souvenir.

|

|

All are but parts of one stupendous whole,

Whose body Nature is, and God the soul.

—Pope’s

Essay on Man.

|

Once within the encompassing walls of the glorious Valley, and the broad shadows of its mighty cliffs are thrown over us like some mystic mantle, fatigued as we may be, every jutting mountain, every pointed crag, every leaping water-fall, has a weird yet captivating charm, that makes us feel as though we were entering some fictitious dreamland. Even the rainbow hues, which are playfully toying with the mists and sprays and beautiful rocket-like forms of the Pohono, or Bridal Veil Fall; or the manifold pearly lights and shades that are intermixing and commingling on that marvelous promontory of vertical granite, known as El Capitan, distributed broadcast as they are, only enhance the delusion. There comes a feeling over us akin to sympathy in the thought-painted picture of Mr. Greeley, when entering the Valley on the eventful first moonlighted night of his visit:—

That first full, deliberate gaze up the opposite height! can I ever forget it? The valley is here scarcely half a mile wide, while its northern wall, of mainly naked, perpendicular granite, is at least four thousand feet high—probably more [since demonstrated by actual measurement to be three thousand three hundred]. But the modicum of moonlight that fell into this awful gorge gave to that precipice a vagueness of outline, an indefinite vastness, a ghostly and weird spirituality. Had the mountain spoken to me in audible voice, or begun to lean over with the purpose of burying me beneath its crushing mass, I should hardly have been surprised. Its whiteness, thrown into bold relief by the patches of trees or shrubs which fringed or flecked it whenever a few handfuls of its moss, slowly decomposed to earth, could contrive to hold on, continually suggested the presence of snow, which suggestion, with difficulty refuted, was at once renewed. And, looking up the valley, we saw just such mountain precipices, barely separated by intervening water-courses of inconsiderable depth, and only receding sufficiently to make room for a very narrow meadow, inclosing the river, to the furthest limit of vision.

Our road up the Valley to the hotels, for the most part, lies among giant pines, or firs, and cedars, from one hundred and seventy-five to two hundred and twenty feet in height, and beneath the refreshing shade of outspreading oaks. Not a sound breaks the impressive stillness that reigns, save the occasional chirping and singing of birds, or the low, distant sighing of the water-falls, or the breeze in the tops of the trees. Crystal streams occasionally gurgle and ripple across our path, whose sides are fringed with willows and wild flowers that are almost ever blossoming, and grass that is ever green. On either side of us stand almost perpendicular cliffs, to the height of nearly thirty-five hundred feet; on whose rugged faces, or in their uneven tops and sides, here and there a stunted pine struggles to live; and every crag seems crowned with some shrub or tree. The bright sheen of the river occasionally glistens among the dense foliage of the long vistas that continually open up before us. At every step, some new picture of great beauty presents itself, and some new shapes and shadows from trees and mountains, form new combinations of light and shade, in this great kaleidoscope of nature; and as we ride along, in addition to the Bridal Veil Fall and El Capitan, we pass the Ribbon Fall, Cathedral Spires, the Three Brothers, and the Sentinel; while in the distance glimpses are obtained of the Yo Semite Fall, Indian Cañon, North Dome, Royal Arches, Washington Tower, Cloud’s Rest, and the Half, or South Dome; all of which expressively suggest the treat there is in store for us, when we can examine them in detail, and enjoy a nearer and more satisfying view of their matchless wonders.

| |

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| The Nevada Fall—Yo-wi-ye. | |

Now, notwithstanding the many objects of interest we have passed, one thought has probably obtruded itself, and it is this, “Shall we ever come up to this or that mountain?” and the length of time consumed in the attempt would seem to give back the nonchalant and unfeeling answer, “Never!” There is, however, no greater proof of the unrealized altitudes of these mountain walls than this—the time it takes to come up with or to pass them. But amidst all these we can possibly hear one ejaculation that seems to contain more real satisfaction in it than any amount of sight-seeing just now. It is this: “Thank goodness, here is the hotel!” Commending ourselves to its most generous hospitalities, we wish our traveling companions a temporary good-by, and prepare for the repast that awaits us.

Our creature comforts having supposably been well cared for at one or other of the hotels, it is natural to infer that the journey, having been more or less fatiguing, has prepared us for a sweet and refreshing sleep; yet experience may prove that the excitement attending our glorious surroundings has cast over us a stronger spell even than that of Morpheus, and charmed us into wakefulness, that we may listen to the splashing, dashing, washing, roaring, surging, hissing, seething sound of the great Yo Semite Falls, just opposite; or has beguiled us into passing quietly out of our resting-place, to look up between the lofty pines and outspreading oaks to the granite cliffs, that tower up with such majesty of form and boldness of outline against the vast ethereal vault of heaven; or to watch, in the moonlight, the ever-changing shapes and shadows of the water, as it leaps the cloud-draped summit of the mountain, and falls in gusty torrents on the unyielding granite, to be dashed to an infinity of atoms. Then, when prudential reasons have wooed us back again to our couch, we may even there have visions of some tutelary spirit of immense proportions, who, in the exercise of his benignant functions, has vouchsafed to us his protecting genius, and admonished the water-fall to modulate the depth and height of its tones somewhat, so that we can sleep and be refreshed, and thus become the better prepared to quaff the delicious draught from this perennial fountain, that only awaits our waking to satisfy all our longings.

There is a possibility, however, that for some time before we are prepared to sing,

“Hail! smiling morn, that tips the hills with gold,”

The sun (hours in advance of a good honest look upon us, per haps, deep down as we are in this awful gorge) may have been up, and painting the rosiest of tints upon the surrounding domes and crags; burnishing up their ridges; gilding trees with blight effects; etching lights and shadows in the time-worked furrows of the mountain’s face, as though he took especial pride in bringing out, strongly, the wrinkles which the president of the hour-glass and scythe has been busily engaged upon for so many thousands of years.

And while we are looking admiringly upon them, please permit me to hazard a suggestion that is born of the experience and teachings of a quarter of a century at Yo Semite. It is this: If it is among the possibilities (and there may exist such a possibility when the subject is well weighed), no matter how tempting the surrounding influences may be—and there is almost sure to be some restless, impetuous, and irrepressible spirit in nearly every party—if you would make your visit healthful, restful, and thoroughly enjoyable, and an ever-present pleasing after-thought, do not attempt any very fatiguing excursion the first day after arrival. Devote it to day dreaming and to rest; not absolutely, perhaps, inasmuch as a modicum of exercise is really better, in a majority of cases, than total inaction; but let it be an easy jaunt among some of the attractive scenes not very far from the hotel.

Before satisfying our expectant curiosity, or gratifying a love for the sublime and beautiful through a closer communion with the marvelous grandeur which surrounds us, permit me to explain what this great Valley is, how it was possibly formed, and the various natural phenomena connected with it; as these may form interesting themes for reflection and conjecture, while we are wandering about among its wonderful scenes.

It is a deep, almost vertical-walled chasm, in the heart of the Sierra Nevada Mountains—here about seventy miles in breadth-about one hundred and fifty miles due east of San Francisco, and thirty from the main crest of the chain. Its sides are built of a beautiful pearl-gray granite of many shades and colors, and are in an infinite variety of forms. These are from three thousand three hundred to six thousand feet in perpendicular height above their base. Over these vertical walls vault numerous water-falls, that make a clear leap of from three hundred and fifty to two thousand feet; besides numerous bounding cascades.

The altitude of the floor of the Valley is nearly four thousand feet above the level of the sea, and the measurements given of the surrounding cliffs and water-falls are mostly from this basis. Its total area within the encompassing walls, according to the report of the Commissioner of the General Land Office, Washington, D. C., comprises eight thousand four hundred and eighty acres, three thousand one hundred and nine of which are meadow land. The entire grant to the State, however, embraces thirty-six thousand one hundred and eleven acres, and includes one mile beyond the edge of the precipices throughout their entire circumference. The Valley proper is about seven miles in length, by from three-quarters to one and a half miles in width; yet the distance between the face of the cliff at the Yo Semite Fall and the Sentinel, according to the measurements of Prof. J. D. Whitney, is two and a half miles. The Merced River, a beautifully transparent stream, full of delicious trout, runs through it, with an average width of

![Scene on the [Merced] River.](images/341.jpg)

|

| SCENE ON THE RIVER. |

The general trend of the Valley is northeasterly and south westwardly, a fortunate circumstance indeed, inasmuch as the delightfully bracing northwesterly trade-winds, which sweep the Pacific Ocean in this latitude during summer, course pleasantly through it, and keep it exceedingly temperate on the hottest of days; so that there is no sultry oppressiveness of atmosphere felt here, as sometimes in the East. Besides this, the sun is afforded the opportunity of looking into the Valley from before six o’clock in the morning until nearly five in the afternoon, during summer, instead of only an hour or two at most, had its bearings been transversely to this. In the short days of winter, however, as the hotels and other buildings are for the most part approximately nearest to the southern wall of the Valley, when Apollo goes farthest on his southern rambles, he looks down upon them over the mountain about half past one in the afternoon, and vanishes at half past three; thus deigning to show his cheerful face only about two hours out of the twenty-four; so that the hotel side of the Valley, so to speak, is mapped in mountain shadow, while the opposite or northern side is flooded with brightness.

Prof. J. D. Whitney, for many years State Geologist, thus expresses his views:*— [* The Yosemite Guide Book, page 81.]

Most of the great cañons and valleys of the Sierra Nevada have resulted from aqueous denudation, and in no part of the world has this kind of work been done on a larger scale. The long-continued action of tremendous torrents of water, rushing with impetuous velocity down the slopes of the mountains, has excavated those immense gorges by which the chain of the Sierra Nevada is furrowed, on its western slope, to the depth of thousands of feet....

The eroded cañons of the Sierra,† [† Ibid., pages 82,83,85.] however, whose formation is due to the action of water, never have vertical walls, nor do their sides present the peculiar angular forms which are seen in the Yosemite, as, for instance, in El Capitan, where two perpendicular surfaces of smooth granite, more than three thousand feet high, meet each other at a right angle. It is sufficient to look for a moment at the vertical faces of El Capitan and the Bridal Veil Rock, turned down the Valley, or away from the direction in which the eroding forces must have acted, to be able to say that aqueous erosion could not have been the agent employed to do any such work. The squarely cut re-entering angles, like those below El Capitan, and between Cathedral Rock and the Sentinel, or in the Illilouette Cañon, were never produced by ordinary erosion. Much less could any such cause be called into account for the peculiar formation of the Half Dome, the vertical portion of which is all above the ordinary level of the Valley, rising two thousand feet, in sublime isolation, above any point which could have been reached by denuding agencies, even supposing the current of water to have filled the whole Valley....

In short, we are led irresistibly to the adoption of a theory of the origin of the Yosemite in a way which has hardly yet been recognized as one of those in which valleys may be formed, probably for the reason that there are so few cases in which such an event can be absolutely proved to have occurred. We conceive that, during the process of upheaval of the Sierra, or, possibly, at some time after that had taken place, there was at the Yosemite a subsidence of a limited area, marked by lines of “fault” or fissures crossing each other somewhat nearly at right angles. In other and more simple language, the bottom of the Valley sunk down to an unknown depth, owing to its support being withdrawn from beneath.* [* The italics are my own to emphasize the substance of Professor Whitney’s views.]

The late Prof. Benjamin Silliman, of Yale College, thought that it was caused through some great volcanic convulsion by which the mountains were reft asunder, and a fissure formed.

Now although I entertain the deepest respect for both those gentlemen, and their views, I am unable to concur in their opinions, for the following reasons: The natural cleavage of the granite walls is not, for the most part, vertical, but at an acute angle of from seventy to eighty-five degrees, as at Glacier Point and the Royal Arches; and that of the Yo Semite Fall is not by any means vertical, to say nothing of the intermediate shoulders between such points as Eagle Tower and the Three Brothers. And although the northern and western sides of El Capitan are more than vertical, as they overhang over one hundred feet, the abutting angle of that marvelous mountain is at an angle of say eighty degrees; while its eastern spur consists of glacier-rounded ridges that project far into the Valley. With this uniform angle of cleavage how could the bottom of the Valley sink down, any more than the key-stone of an arch? unless by the displacement of its supporting base; and, to concede this possibility, is to admit the theory of Professor Silliman of the violent rending of the mountains asunder by volcanic co-action, which, in my judgment, is unsupported by convincing data.

To admit this contingency, moreover, is to pre-suppose the entire uplifting and rending of a large proportion of the solid granite forming the great chain of the High Sierra; and then of its having left only this particular fissure to mark the co-action that then took place—a possible but not probable result. It is even more than improbable, from the fact that the solidified granite crossing every one of its side cañons, even near to the Valley, is everywhere completely and visibly intact, so that there is not the slightest semblance of any disjunction whatsoever. To my convictions, therefore, the evidences that the Yo Semite Valley was ever formed by either subsidence, or volcanic rending, are not only unsatisfactory, but are entirely absent.

Nor is it altogether clear why Professor Whitney, after giving his emphatic opinion that “the long-continued action of tremendous torrents of water, rushing with impetuous velocity down the slopes of the mountains, has excavated those immense gorges by which the chain of the Sierra Nevada is furrowed, on its western slope, to the depth of thousands of feet,” should make the Yo Semite Valley an exception; especially when the premises are so abundantly clear that it was created by precisely similar agencies as those of other cañons—that of erosion. To illustrate this, let me call attention to some interstices in the face of a jutting spur of the southern wall of the Valley, about midway between the Sentinel and Cathedral Spires (see engraving), known as

One of these is several hundred feet in depth, and yet not over three and a half feet across it. But for its rounding edges one could stand upon its top, look into its mysterious depths, and then step across it to the other side. There can exist no doubt that this has been formed from a soft stratum of granite, just the width of the fissure; and as that there is not the smallest stream of water running through it (except when it rains), as the elements have disintegrated the demulcent rock, every storm of wind, or rain, or snow, had kept constantly removing the friable particles and left only the hard walls standing.

| |

| Photo by S. C. Walker. | Per drawing by Mrs. Brodt. |

| THE FISSURE. | |

Making this a basis of conclusions, is it not reasonable to suppose that there once existed similar strata where the Valley now is, and that as the disintegrating agencies completed their work upon it, the denuding torrents of the Sierra swept over or through it, and carried off the disintegrated material to build the plains and valleys below? Stand upon any of the bridges which now span the Merced River, during high water, and the floating silica with which it is laden will be conclusive evidence that the same forces, on a comparatively limited scale, are still actively going on.

Nor has water, in its liquefied form at least, been the only potential agency for cutting down and hewing out chasms like this among the High Sierra, inasmuch as its polished valley floors, burnished mountain-sides and tops, and vast moraines, many thousands of feet in altitude above the Valley, prove, beyond per adventure or question, that glaciers of immense thickness once covered all this vast area; filling every gorge, roofing every dome, and overspreading every mountain ridge with ice; the trend of whose striations is unmistakably towards the channel of the Merced River, mainly through its tributaries. As the Yo Semite Valley is but four thousand feet above sea level, and these glacial writings are distinctly traceable not only on the walls of the Valley and the cliffs above it, but nearly to the summits of the highest mountains east of it (here over thirteen thousand feet in altitude) there can be but little doubt that a vast field of ice had pre-existence at Yo Semite that was over a mile and a half in absolute thickness and depth! Who, then, can even conceive, much less estimate, the cyclopean force, and erosive power, of such a glacier? It would seem that plowing into soft rock, teming away of projections, loosening seamy blocks, detaching jutting precipices, grinding off ridges, scooping out hollows for future lakes, and forcing everything movable before it, would be a mere frolicsome pastime to so irresistible and mighty a giant. And, when that pastime has been indulged in for countless ages, its results may be imagined, but cannot be comprehended.

This, then, in my judgment, has been no insignificant factor in broadening and deepening the chasm first cut here, as elsewhere, by water; and indicating, if not proving, that the Yo Semite Valley was formed by erosion, and not by volcanic action.

In a personal conference with Prof Wm. H. Brewer, formerly first assistant of the State Geological Survey of California, now of Yale College, New Haven, Connecticut, the question was asked him, “In about what age of the world was the glacial period supposed to have existed?” and the answer was, “This has not been positively agreed upon by scientists, as some think it was about twenty or thirty thousand years ago, others from fifty to eighty thousand, and some contend that nearly one hundred and fifty thousand years have elapsed since that time, and it may have been even more.” As something will be said about this, and about the moraines of the High Sierra when we take our mountain jaunts beyond the Yo Semite, further present mention will be unnecessary.

The thermometer seldom reads higher than eighty-six degrees in summer, or lower than sixteen degrees in winter, although it has been ninety-five degrees (and even then the heat was not oppressive, owing to the rarefaction of the atmosphere), and nearly to zero—never below it. The usual ice-harvesting season is from December 15th to 25th, when the days are clear, and the temperature at night ranges from sixteen to twenty-five degrees; at which time ice forms from six to eleven inches in thickness, and is then taken from the sheltered eddies of the river. A good quality of ice is seldom attainable after the rains and snows of winter have fairly set in.

The first fall rain generally occurs about the time of the autumnal equinox, in September; but does not continue more than a day or two; when it usually clears up and continues fine for several weeks. It is after this rain that the first frost generally pays its timely visit, and commences to paint the deciduous trees and shrubs in the brightest of autumnal colors. Early in November the first snow generally begins to fall, when it will probably not deposit more than a few inches in the Valley, but prove more liberal in the mountains, where it sometimes will leave fifteen or twenty inches. It was in one of these storms that Lady Avonmore, better known as the Hon. Theresa Yelverton, was caught, alone, and being lost and benighted, came near losing her life. A few days thereafter the delightfully balmy Indian summer weather sets in, and continues to near the end of December; when old Winter, he with the hoary locks and unfeeling heart, swoops down in good earnest; and, turning his frosty key, keeps the inhabitants of Yo Semite—generally about forty in number—close prisoners until the benignant smiles of the gentle angel, Spring, unlocks the snowy doors, and again sets them free.

The pluvial downpour of an average winter in Yo Semite is usually from twenty to thirty-three inches, and of snow from nine to seventeen feet. It must not, however, be supposed that this falls all at once, or that it ever aggregates so great a depth, as it keeps melting and settling more or less all the time; so that I have never known it to exceed an average depth over the Valley of more than five and a half feet. Snow possesses the wonderful quality of keeping the temperature of anything upon which it falls, about the same as it finds it; so that if the ground which it covers is warm, it is kept in that condition, and the snow melts rapidly from beneath; but, should the earth be frozen, it retains that temperature, and liquefies mostly from above.

To enable visitors to see every point of interest to the greatest advantage, the State, through its Board of Yo Semite Commissioners, has constructed a most excellent carriage road throughout the entire circumference of the Valley; and which, including that to Mirror Lake and the Cascade Falls, opens up a drive of over twenty-one miles, that has not its equal in scenic grandeur and beauty anywhere else on earth.

In addition to this, broad, safe, and well-built trails for horseback riding have been made up the cañon of the Merced River to the Vernal and Nevada Falls; over old moraines, to the summit of Cloud’s Rest, and to the foot of Half Dome; up the mountain-sides to Union Point, Glacier Point, and Sentinel Dome, to Columbia Rock, the foot and top of the upper Yo Semite Fall, and Eagle Peak, so that impressive views may be enjoyed of these by an actual visit to and among them. Earlier enterprises of this kind were inaugurated by private individuals, and tolls collected for passing over them; but they were all subsequently purchased by the State and made free. To each and all of which it is proposed to make excursions in due season; so that when the traveler has journeyed so far to witness these glorious scenes, nothing of importance may be omitted, that could in any measure tend to insure their being visited understandingly, and as intelligently as possible.

As there are frequently moments of leisure that visitors desire to utilize, besides having wants that need to be supplied, perhaps it may be as well here, as elsewhere, to enumerate the various interests represented in the little settlement of Yo Semite. Of course the first to be mentioned are the

Four when the new one now building is completed. These are kept by Mr. J. K. Barnard, Mr. J. J. Cook, and Mr. and Mrs. G. F. Leidig, each of which is generally called after the name of its proprietor; as, “Barnard’s,” “Cook’s,” and “Leidig’s.” The latter is the first reached, Cook’s the next, and Barnard’s is the farthest up the Valley, near to the iron bridge. The latter can accommodate about one hundred guests; Mr. Cook, about seventy-five; Mr. Leidig, forty; and the new hotel is sufficiently commodious to take care of one hundred and fifty. All of these are comfortable, and the prices charged are reasonable, especially considering their distance from market, and the shortness of the business season.

![The Big Tree Room, Barnard’s [Hotel].](images/349.jpg)

| |

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | |

| THE BIG TREE ROOM, BARNARD’S. | |

When you are within this room, and your eye falls upon any one of the creations of his genius, you can see at a glance that Mr. Sinning has the rare gift of uniting the taste of the artist with the skill of the workman. His choice specimens of various woods, found in this vicinity, most admirably joined, and beautifully polished, are so arranged that one colored wood is made complimentary to that of the other adjoining it. They are simply perfect, both in arrangement and mechanical execution. Then, it gives him such real pleasure to show you, and explain all about his work, that his eyes, seen through a single pair of glasses, actually double in brightness when you admire it. Nor need you be afraid of offending him if you do not purchase, as he readily sells all that he can make, notwithstanding he is at his bench on every working day, both winter and summer, making and finishing the most beautiful of ladies’ cabinets, glove-boxes, etc., etc.

Of these, there are two, Mr. Thomas Hill’s, and that of Mr. Charles D. Robinson; the former is near Cook’s Hotel, and the latter adjoins the Guardian’s office. The moment that either studio is entered, the works of each pleasantly impresses visitors with their unquestioned excellence and faithfulness to nature. And while every true artist is in thought and feeling more or less a poet, and these ethereal essences are noticeably present in, and breathe through every line and color of his touch, there is frequently as wide a difference in their treatment of the subject, as there is between the poetry of Shakespeare and that of Tennyson. And it is well that it is so, for in art, as in food, it is the rich variety that makes pleasing provision for all. The thought-coloring of Mr. Hill may differ widely from that of Mr. Robinson, and it does; but in that very difference lies the secret of the measurable success of both. The beautiful creations of either will worthily occupy any picture gallery, or drawing-room on earth, should visitors desire to live these scenes over again when within their own far-off homes, by leaving with Mr. Hill, or Mr. Robinson, their orders for pictures.

Of course photographs have become one of the popular luxuries of the age, and there is scarcely an intelligent visitor that enters the Valley, who does not wish to carry home, for himself or friends, some souvenir of his visit; and to renew pleasant memories of its marvelous scenes. To supply this want there are two galleries established; one, conducted by Mr. Geo. Fiske—to whom I am largely indebted for so many of the beautiful illustrations that appear in this book—who, as a man, a gentleman, and an artist, is in every way worthy of the most liberal patronage that can be extended to him; and the other is kept by Mr. G. Fagersteen, who, while being devoted to his art, is among the best residents of Yo Semite, and who, like Mr. Fiske, takes groups of visitors which embody the views around, as a background to the picture. There are also two other places where photographic views of the surrounding scenery are sold, Mr. J. J. Cook’s, and at the Big Tree Room, Barnard’s; the former having Taber’s, and the latter Fiske’s.

For general merchandise is kept by Mr. Angelo Cavagnaro, an Italian; and who, you will find, has on hand almost any article that may be desired, from a box of paper collars to a side of bacon; and probably many others that neither you nor any one else may want.

Mrs. Glynn is an industrious woman, who, finding it impossible to breathe the air of a lower altitude, has prolonged her useful life by making choice of Yo Semite as a home; and, being a good cook, ekes out a frugal living by selling bread, pies, and such things, to transient customers; and by keeping two or three boarders.

These are kept by Messrs. Wm. F. Coffman and Geo. Kenney, two wide-awake, square men, who wait upon guests at the hotel every evening to learn their wishes concerning the rides around the Valley in carriages, or up the mountains on horses, for the next day. When they present themselves, it will be well for visitors to have considered their plans for the morrow, and give to them their order accordingly; as, by so doing, all delays, and many annoyances, are avoided in the morning. The charges for saddle horses and carriages are determined by the Board of Commissioners. Should any irregularity of any kind occur it should be promptly reported to the Guardian. Additional to the gentlemen above mentioned, Mr. Galen Clark (one of the oldest pioneers of this section, and who for sixteen years was the Valley’s Guardian) has also the privilege of conveying passengers in his carriage to every point of interest around Yo Semite. He will be found intelligent, obliging, and efficient in everything he undertakes.

Of course when any one wishes to witness the scenic grandeur visible from the mountain-tops which surround the Valley, he is at liberty to elect whether these trips shall be taken on horseback or afoot. If on foot, he avoids all care and expense for either himself or his horse; but finds it very fatiguing. If on horseback, a guide is needed, not only to explain the different objects of interest to be found, but to look out for the safety and comfort of those in his care; and to insure these, saddles have to be carefully watched, and adjusted, on all mountain trails. These form important parts of a guide’s duty. The day’s expense for a guide (which includes his horse, board, and wages) is $3.00, divided between the different members of the party. For instance, to a party of six—and none should be larger than this if a guide is expected to do his full duty by it—the pro rata for each person would be fifty cents for his day’s service.

To mention even the names of the many whose kindly attentions and really valuable services as guides, have been more or less before the Yo Semite visiting public for the last twenty-five years, would make many a visitor’s heart warm with grateful emotion; and to recall to memory the faces, and with them the obliging acts and excellent qualities of those who were thus personally useful to them, in the “long, long ago.” Many of these could be given, but the restraining fear that a treacherous memory might cause some to be omitted, that were equally worthy of a place, is suggestive of possible yet unintentional injustice, that is sufficiently strong to tempt me to forego the record altogether.

Still, there is one of the present guides whose peculiar characteristics, singular ways, and husky voice, make him “the observed of all observers,” whose name is Nathan B. Phillips, but who is better known to all the world as “Pike.” Being among the oldest and longest in the service of any now acting in the capacity of guide, permit me to introduce him:—

If, when you present this letter of introduction, he should not recognize the fact that you are addressing him by his own name, you have only to add the proud cognomen of “Pike,” to convince him that, for the moment at least, he was a little absent-minded! Now when Pike is himself (as once in a while he gets “socially” inclined) no better guide ever took care of a party; as he is polite, studiously attentive without seeming so, patient, thoughtful, careful; and there is not a peak or gorge, valley or cañon, in the whole range of the High Sierra, within view, that is not “as familiar to him as household words.” Besides, he can trail a bear, track a deer, bag a grouse, and work off agonizing music from a violin with the best. I do not say that there are not others equally good, as either hunter, guide, or violinist, for that would not be true; and would, moreover, be begging the question. I never saw him angry but once, and that was when a miserable wretch, sometimes inappropriately called a man, was abusing a horse. Then, in language, he “made the fur fly;” and I said, Amen! Once he was asked by a lady how the huskiness of his voice was brought about. “Ah,” he good-naturedly responded, “telling so many ‘whoppers’ to tourists, I expect!” Pike is a Yo Semite character, and one worth meeting.

|

| MR. NATHAN B. PHILLIPS. |

When meal-times come we should feel it a great omission had the former been overlooked; and when traveling on our own horse tells us he has lost his shoe, or in our own conveyance we find that a spring has broken, a bolt is gone, or a nut lost, how gladly we welcome the blacksmith and his shop. Both of these are found in Yo Semite.

This is near the camp-ground set apart by the Board of Commissioners for the accommodation of those who leave the scorching plains below for the respite and comfort of recuperation in such a charming spot as Yo Semite, and come in their own conveyances; generally bringing their own tents and supplies with them, and camp out. As Mr. A. Harris grows and keeps an abundant supply of fodder, besides stabling for animals, his place is deservedly popular with camping parties. Milk, eggs, and other farm products are obtainable here; and, should the bread burn at the camp-fire, and the yeast become sour, Mrs. Harris has always the remedy on hand to help strangers out of their difficulty, and that most cheerfully. Then, next to the Leidig’s, the Harris’ have the largest family in the Valley; both being a source of pleasurable pride to the parents. Speaking of children, it must not be forgotten that there is here

It is situated on the margin of a small meadow just above Barnard’s; with the North Dome, Royal Arches, Washington Tower, and Half Dome, lifting their exalted proportions heavenward, just in front of the school-house door. Then there is

This neat little edifice, devoted to the worship of God amid the marvelous creations of His hand, was built by the California State Sunday School Association, in the summer of 1879; partly by subscriptions from the children, but mainly from the voluntary contributions of prominent members of the Association. Mr. Charles Geddes, a leading architect of San Francisco, made and presented the plans; and Mr. E. Thomson, also of San Francisco, erected the building, at a cost of between three and four thousand dollars. It will seat an audience of about two hundred and fifty. Mr. H. D. Bacon, of Oakland, gave the bell; and when its first notes rung out upon the moon-silvered air, on the evening of dedication, it was the first sound of “the church-going bell” ever heard in Yo Semite. Let us hope that it will assist to

|

“Ring out the false, ring in the true,

[* Tennyson’s Ring Out, Wild Bells.] |

Miss Mary Porter, of Philadelphia, donated the organ, in memorium of Miss Florence Hutchings, the first white child born in Yo Semite, who passed through the Beautiful Gate, September 20, 1881 (as recorded on pages 145, 146), to whom she had become devotedly attached while visiting the Valley the preceding year.

The Yo Semite Chapel is for the free use of Christians of every denomination.

| |

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Engraved by J. M. Hay, S. F. |

| THE YO SEMITE CHAPEL. | |

Is a State officer, appointed by the Board of Commissioners, for the purpose of watching over the best interest of the Valley, and superintending the local details connected with its management, under the Board. To him, therefore, all irregularities of every kind should be promptly reported, to insure their abatement. From him, moreover, can be obtained information, not only concerning the rules and regulations adopted by the Board of Commissioners, for the management of the Valley in the interests of the public; but the best places to camp, the points most noteworthy to see, and the best time and manner of seeing them; with answers to every reasonable question intelligent persons may ask concerning this wonderful spot. In short he will, to the best of his ability, be the living embodiment of a cyclopedia of Yo Semite; and that politely, cheerily, and pleasantly. The present Guardian of the Valley is Mr. Walter E. Dennison, to whom all communications concerning it should be addressed. His office is on the south bank of the Merced River, near the upper iron bridge.

Both of these invaluable institutions, of especial interest to the traveling public, as well as residents, have been established at Yo Semite. The former opens and closes with the business season, but the latter maintains connections with the outside world all the year—in summer, daily, and in winter, by a semiweekly mail. Notwithstanding the unquestioned efficiency of Wells, Fargo & Co.’s Express for the conveyance of valuable packages, Yo Semite should be made a “Money-order Office” of the postal service, as the wants of tourist visitors, as well as residents, would be much subserved thereby.

Before the establishment of a postal route to, and post-office at Yo Semite, all letters and papers were carried thither by private hands; but the late U. S. Senator Howe, of Wisconsin, afterwards Postmaster-General of the United States, secured this great boon for the Valley. Through him the writer became its first postmaster, at the enormously extravagant salary of $12.00 per annum, besides perquisites of uncalled-for old papers and quack advertisements! But as there was then no winter service, and he sometimes paid his Indian mail carrier ten dollars for a single winter trip, besides board and old clothes for trudging through and over snow, in the dead of winter, without snow-shoes, to bring in the precious missives; strange as it may seem, it was not deemed a sufficient sinecure to incite and tempt the envious longings of needy politicians for its possession!

For many years the Valley was in telegraphic communication with the outside world, via Sonora and Groveland; but as it was not sufficiently patronized after 1874 to pay for repairing the line and running the office, in a few years thereafter it went unrepaired, and was consequently unused. In 1882, however, a new one was constructed, by the Western Union Company, which is still maintained, via Berenda, Grant’s Sulphur Springs, and Wawona to Yo Semite; so that now telegrams can be sent thence to every nook and corner of civilization.

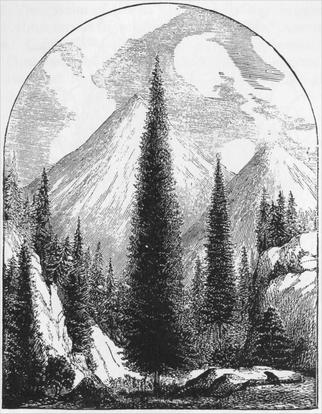

There are four different species of pine growing here: Two “Yellow Pines,” Pinus ponderosa, and P. Jeffreyi, with three needles to each leaf; “Sugar Pine,” P. Lambertiana, having five needles to a leaf; and the “Tamarack Pine,” P. contorta, with only two to a leaf. “Red, or Incense Cedar,” Libocedrus decurrens: Three “Silver Firs,” Abies concolor, A. grandis, and A. nobilis.

There is but one more of this genus found in the State, and that one only in a single locality (the Santa Lucia Mountains, Monterey County), but, owing to its beauty, and rarity, I am tempted to introduce engravings of it here. All the cones of the silver fir grow upwards,—not downwards, like the pines.

|

| THE SILVER FIR, Abies Bracteata, Santa Lucia Mountains. |

Of the coniferae, the next in importance, perhaps, is the “Red” or “Douglas” Spruce, Psudo tsuga Douglasii. Then, in resemblance of foliage, its single leaves sharp as a needle, and fruit like a nutmeg, whence comes the name “California Nutmeg,” Torreya Californica. Then follows the “Black Oak,” Quercus Kelloggii, upon the acorns of which the Indians mainly depend for their staple bread-stuff;* [* See Chapter on Indian manners and customs.] and a few of the “Quaking Aspen,” Populus tremuloides which came down from the mountains in the flood of 1867. The “Balm of Gilead” Poplar, Populus balsamifera: “Alder,” Alnus vifidis: “Rock,” or “Oregon, Maple,” Acer macrophyllum: “California Laurel,” Umbellulafia Californica: “Dog wood,” Cornus Nuttallii, with its large white blossoms. Then follows the most beautiful of all the “Live Oaks,” the golden cupped Quercus chrysolepis.

|

| Drawn from nature by A. Kellogg, M. D. |

| CONE OF THE SILVER FIR, Abies Bracteata, Santa Lucia Mountains. |

The most attractive of all, on account of the bright green of its leaves, its dwarf, bell-shaped, and waxy bunches of pinkish white blossoms, and the red olive-green of its smooth stems, the bark of which peels off annually, is the “Manzanita,” Arctostaphylos pungens. Next comes the “California Lilac,” Ceanothus integerrimus, whose large feathery plumes of white flowers, redolent with perfume, that become so inviting to both the eye and nostril; with its bright sap-green bark: The “Azalea,” Azalea Occidentalis, the fragrant masses of whose pinkish-white or yellowish-white blossoms can be “scented from afar:” The “Spice Plant,” Calycanthus Occidentalis, that grows in such rich abundance on the way to Cascade Falls, and whose large deep-green and pointed ovate leaves shine in striking contrast to its wine-colored flowers. Nor must we overlook the “Chokecherry,” Prunus demissa, with its gracefully depending blossoms, and fruit so valuable an edible to the natives; or the “Wild Coffee,” Rhamnus Californica, whose root-wood makes such beautiful veneers. These, with some few others, are the principal representatives of the interesting shrubbery of the Valley.

These are so numerous and so varied that but a few only can here be mentioned. Perhaps the first claiming attention, not only for its graceful tulip-like cup, and richly colored butterfly wing-formed petals, but from its being the flower after which this county was named, “Mariposa,” or “Butterfly Tulip,” Calochortus venustus: The “Penstemon,” Penstemon loetus, with its bright purplish-blue flowers: “Pussy’s Paws,” Spraguea umbellata, whose attractive, radiating bunches clothe even sandy places with beauty; Hosackia crassifolia, with its singular clover-like blossoms and vetch-like leaves, the young shoots of which form such tender and delicious greens for the Indians; the “Evening Primrose,” Oenothera biennis, that brightens the meadows at eventide with its golden eyes of glory, but which closes when the sun looks too steadfastly into them at midday; or its dark-purplish rose-colored twin sister, the Godetia, that forsakes the moist meadow land to grow on sandy slopes. But there is such a fascinating charm in these delicate creations that one may be easily tempted to linger too long in their delightful company.

Mr. J. G. Lemmon, of Oakland, and his talented wife, who have made this interesting family a loving and special study, have kindly sent me the following carefully prepared list of those found here:—

Common Polypody, Polypodium vulgare; California Polypody, P. Californicum; California Lip Fern, Cheilanthes Californica; Graceful Lip Fern, C. gracillima; Many-leaved Lip Fern, C. myriophylla; (Prof.) Brewer’s Cliff-brake, Pelloea Breweri; Heather-leaved Cliff-brake, Pelloea andromedoefolia; Wright’s Cliff-brake, Pelloea Wrightiana; Short-winged Cliff-brake, Pelloea brachyptera; Bird-foot Cliff-brake, Pelloea ornithopus; Dwarf Cliff-brake, Pelloea densa; Bridges’ Cliff-brake, Pelloea Bridgesii; Rock-brake, Cryptogramme acrostichoides; Common bracken, Pteris aquilina, var. lanuginosa; Venus’ hair, Adiantum Capillus-veneris; California Maiden hair, Adiantum emarginatum; Foot-stalked Maiden hair, Adiantum pedatum; Greek Chain fern, Woodwardia radicans; Lady fern, Asplenium Filixfoemina; Alpine Beech fern, Phegopteris alpestris; Rough Shield fern, Aspidium rigidum, var. argutum; Armed Shield fern, Aspidium munitum; Naked Shield fern, Aspidium munitum, var. nudatum; Over-lapped Shield fern, Aspidium munitum, var. imbricans; Sharp-leaved Shield fern, Aspidium aculeatum; Sierra Shield fern, Aspidium aculeatum, var. scopulorum; Delicate Cup fern, Cystopteris fragilis; Hairy Woodsia, Woodsia scopulina; Oregon Woodsia, Woodsia Oregana.

Simple Grape fern, Botrychium simplex; Southern three-parted Grape fern, Botrychiumternatum, var. australe; Virginia Grape fern, Botrychium Virginianum; Common Adder tongue, Ophioglossum vulgatum.

To those who are interested in this attractive family, the above complete synopsis, which embraces every species and variety yet found within and around the Valley, will be especially acceptable

“Are there trout in that pellucid and beautiful stream flowing past us?” inquired a somewhat fancifully dressed young gentleman with a distingue air, equipped with the latest patented fishing-rod, and a large book well filled with flies of the most approved color and pattern.

“Yes, Sir, speckled mountain trout. There are but two kinds of fish found in this river, or in any of its tributaries, speckled trout and sucker; the former swim near the surface, ready to catch the first fly that comes along, and the latter float near the bottom of the stream, upon the lookout for worms, or offal of any kind that may be drifting down. Trout, as you find, are a delicious table fish; but no one, except Indians, will think of eating sucker.”

“Is there any good place near here for a little sport of that kind? as I think I should like to try my hand at that sort of thing, you know.”

“Oh! yes, almost anywhere; they are just where you can see and find them; but, if they should see you first you had better move on to the next pool or riffle, as you would be wasting your time there.”

“Oh! I thank you very much, as trout-fishing is such delightful sport, you know.”

Apparently full of ruminating anticipation, our hero of the rod and line sauntered leisurely along, occasionally testing the flexibility of his pole by whipping it after some imaginary trout, until he disappeared behind a clump of young cottonwoods, to be seen no more until dinner-time. But “when the evening shades prevail”-ed, the would-be disciple of Isaac Walton could be seen advancing slowly, and somewhat disconsolately, towards the hotel, with one small, deluded trout dangling at the end of a twig. Simultaneously, as if with mischievous “malice aforethought,” an Indian walked briskly up with about as large a string of trout as he could conveniently carry. Now this was the additional feather that broke the camel’s back, and our crest-fallen friend looked bewildered and dumbfounded. Placing his solitary eyeglass firmly in front of his left eye, he fixed the discomfited gaze of that one eye (glass) alternately upon the Indian, and then upon the successful “catch” that was hanging at the Indian’s side; and as soon as he could discover that he could find a voice, he falteringly inquired, “What do you use for bait?”

|

An artist friend being present, made the accompanying graphic sketch of this soul-harrowing scene.

The general absence here of what is termed “good luck” among anglers, has fabricated the trite aphorism among visitors that, “It takes an Indian to catch trout at Yo Semite.” And this is in a great measure true; yet, it must not be supposed that his uniform success in the art is altogether attributable to his superior skill. By no means. It is to be accredited more to his knowledge of the haunts and habits of trout, which that wonderful mother, Necessity, has persistently taught him from childhood; and by which he learns where to find them at the different seasons of the year, and in the varying stages of water. This is an advantage that is unshared by the stranger. Then, the old proverb, that “practice makes perfect,” has not a little to do with an Indian’s invariable success, especially as his bread and dinner depend upon it. Admitting, however, that skill and practice go hand in hand with an Indian, to bring fish to his string, I have seen white adepts in the art that could largely discount an Indian’s best efforts.

The most matter-of-fact manner of catching trout among unskilled and unpracticed anglers, is, to cover up the hook completely with a good-sized worm, and then cause it to float gently down to where he can see some suckers apparently resting on the bottom of the stream; and, when he sees the tempting morsel fairly in the mouth of his intended victim, to suddenly jerk in the line. Thus captured the sucker is laid carefully away until night-fall, when he is cut up into pieces about a quarter of an inch in thickness and half an inch square; and which, when placed snugly on the hook, become an inviting bait to trout, which it readily seizes, and is himself seized in turn, to supply breakfast for the angler and his guests. Good fishing places, free from roots and sticks, and well stocked with trout, should be sought quietly out in the day-time.

In early days the Indians fished only with the spear (in which some were adepts), and with the worm; but in these latter days they avail themselves of the lessons taught them by the whites, of using sucker as bait, and fishing at night; by which they are enabled to bring such large strings of trout to the hotels, for which they invariably receive twenty-five cents per pound.

As it is reasonably presumable that every one before starting out upon any of the many interesting trips within and around the Valley, will be desirous of ascertaining not only their particular direction and location, but the distances thereto, the following tables, and accompanying map, are herewith submitted.

Before setting out upon any of our excursions around or beyond the Valley, it seems desirable to state that, according to Lieutenant Wheeler’s U. S. Survey, from which much of this data concerning altitudes here is taken, its elevation above sea level as computed from the floor of the upper iron bridge, near Barnard’s, is three thousand nine hundred and thirty-four feet; and that all the measurements of the cliffs and water-falls about the Valley are calculated from this basis, except where otherwise stated.

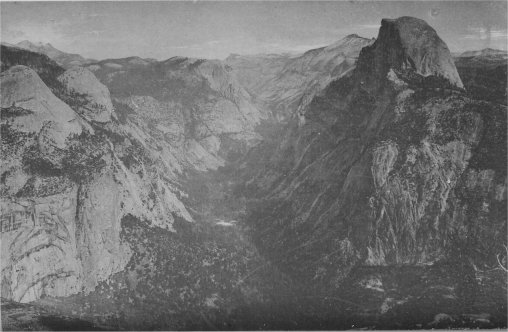

| |

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| The Sentinel—Loya,—El Capitan and Valley. | |

| From Glacier Point Trail (See pages 467-68.) | |

For the purpose of enabling visitors to make their respective jaunts understandingly, I have thought it desirable to present the various points of interest somewhat in detail, and in the order they are generally preferred to be seen; but which order can, of course, be changed according to circumstances, or to individual taste and preference. With the reader’s permission, therefore, we will suppose that we are now prepared to set out upon our glorious pilgrimage among the marvelous scenes which surround us, and are standing upon the floor of the upper iron bridge, three thousand nine hundred and thirty-four feet above sea level, and looking into the transparent waters of

This musical and suggestive name was given to it by the old Spanish padres, by whom it was called Rio de la Merced, the River of Mercy. And, by the way, we are much indebted to the poetical taste of those old missionaries for a number of apposite names that embellish the California map; such, for instance, as the Rio de Sacramento, the River of the Sacrament; Rio de las Plumas, the River of Feathers; Ciudad Los Angeles, the City of the Angels, and many others. The view, easterly, reveals the “Half Dome,” framed by a vista of overarching pines, cedars, oaks, and balm of gileads, that stand on the margin of the river; westerly the lofty, sky-piercing crest of “Eagle Peak” is seen through a similar portal, about both of which more will be said hereafter.

|

TABLE OF DISTANCES.

From the Guardian’s Office, near the Upper Iron Bridge, to Different Points of

| |||||

| POINTS OF INTEREST. | Between Con- secutive Points. | From Guard- ian’s Office. | To Guardian’s Office | Altitude in feet above Yosem- ite Valley | Altitude in feet above Sea Level |

| To Mirror Lake (by carriage Road).

From Guardian’s Office to— |

.... | .... | 2.91 | .... | 3,934 |

| Indian Cañon Bridge | 0.65 | 0.65 | 2.26 | .... | .... |

| Harris’ Residence | 0.56 | 1.21 | 1.70 | .... | .... |

| Forks of Tis-sa-ack Avenue Road | 0.95 | 2.16 | 0.75 | .... | .... |

| Mirror Lake | 0.75 | 2.91 | .... | 174 | 4,108 |

If the return is made via Tis-sa-ack Avenue, the distances from Mirror Lake are— |

.... |

.... |

3.70 |

.... |

.... |

| Upper Forks of Tis-sa-ack Avenue Road | 0.61 | 0.61 | 3.09 | .... | .... |

| Ten-ie-ya Creek Bridge | 0.17 | 0.78 | 2.92 | .... | .... |

| Tis-sa-ack Bridge | 0.89 | 1.67 | 2.03 | .... | .... |

| Guardian’s Office | 2.03 | 3.70 | .... | .... | 3,934 |

Tis-sa-ack Avenue Drive. From Guardian’s Office to— |

.... |

.... |

5.18 |

.... |

.... |

| Tis-sa-ack Bridge | 2.03 | 2.03 | 3.15 | ... | ... |

| Ten-ie-ya Bridge | 0.89 | 2.92 | 2.26 | .... | .... |

| Harris’ Residence | 1.05 | 3.97 | 1.21 | .... | .... |

| Guardian’s Office | 1.21 | 5.18 | .... | .... | 3,934 |

To Bridal Veil Fall, Artist Point, and New Inspiration Point (by carriage road)— From Guardian’s Office to— |

.... |

.... |

7.19 |

.... |

.... |

| Cathedral Spires Bridge | 2.50 | 2.50 | 4.69 | .... | .... |

| El Capitan (lower iron) Bridge | 1.13 | 3.63 | 3.56 | .... | 3,925 |

| Bridal Veil Fall | 0.41 | 4.04 | 3.15 | .... | .... |

| Forks of Pohono Avenue Road | 0.28 | 4.32 | 2.87 | .... | .... |

| Artist Point | 1.48 | 5.80 | 1.39 | 800 | 4,651 |

| Cabin | 0.43 | 6.23 | 0.96 | 1,000 | 4,851 |

| New Inspiration Point | 0.96 | 7.19 | .... | 1,500 | 5,371 |

To the Cascade Falls (by carriage road). From Guardian’s Office to— |

.... |

.... |

7.87 |

.... |

.... |

| Forks of Big Oak Flat Road | 3.66 | 3.66 | 4.01 | .... | 3,944 |

| Black Springs | 0.69 | 4.35 | 3.32 | .... | .... |

| River View | 0.19 | 4.54 | 3.13 | .... | .... |

| Pohono Bridge | 1.29 | 4.83 | 2.84 | .... | .... |

| Cascade Falls | 2.84 | 7.67 | .... | .... | 3,225 |

The Pohono Avenue Drive. From Guardian’s Office to— |

.... |

.... |

10.45 |

.... |

.... |

| Yo Semite Creek Bridge | 0.49 | 0.49 | 9.96 | .... | .... |

| Rocky Point | 0.96 | 1.45 | 9.00 | .... | .... |

| Indian Camp | 0.37 | 1.82 | 8.63 | .... | .... |

| Ribbon Fall | 2.17 | 3.99 | 6.46 | .... | .... |

| Forks of Big Oak Flat Road | 0.07 | 4.06 | 6.39 | .... | 3,949 |

| Black Springs | 0.69 | 4.75 | 5.70 | .... | .... |

| River View | 0.25 | 5.00 | 5.45 | .... | .... |

| Pohono Bridge | 0.29 | 5.29 | 5.16 | .... | .... |

| Fern Spring | 0.19 | 5.48 | 4.97 | .... | .... |

| Moss Spring | 0.06 | 5.54 | 4.91 | .... | .... |

| Forks of Big Tree Station Road | 0.59 | 6.13 | 4.32 | .... | .... |

| Bridal Veil Fall | 0.28 | 6.41 | 4.04 | .... | .... |

|

TABLE OF DISTANCES—Continued. | |||||

| POINTS OF INTEREST. | Between Con- secutive Points. | From Guard- ian’s Office. | To Guardian’s Office | Altitude in feet above Yosem- ite Valley | Altitude in feet above Sea Level |

| El Capitan Bridge | 0.41 | 6.82 | 3.36 | .... | 3,925 |

| Cathedral Spires Bridge | 1.13 | 7.95 | 2.50 | .... | .... |

| Leidig’s Hotel | 1.43 | 9.38 | 1.07 | .... | 3,934 |

| Cook’s Hotel | 0.30 | 9.68 | 0.77 | .... | 3,934 |

| Cosmopolitan Billard Hall | 0.73 | 10.41 | 0.04 | .... | 3,934 |

| Barnard’s Hotel | 0.04 | 10.45 | .... | .... | 3,934 |

The Round Drive on the Floor of the Valley. |

|||||

| From Guardian’s Office, via Merced, Ten-ie-ya, Yosemite, and Pohono Bridges, and back |

15.06 | .... | .... | .... | .... |

| Including Mirror Lake and Cascade Falls | 21.32 | .... | .... | .... | .... |

To Foot of Lower Yo Semite Falls. |

.... |

.... |

0.90 |

.... |

.... |

| From Guardian’s Office to— | |||||

| Yo Semite Creek Bridge | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.41 | .... | .... |

| Foot of Fall | 0.41 | 0.90 | .... | .... | .... |

To Top of Yo Semite Fall and Eagle Peak, by Trail. |

.... | .... | 6.59 | .... | .... |

| From Guardian’s Office to— | |||||

| Columbia Rock | 1.98 | 1.98 | 4.61 | 1,154 | 5,088 |

| Foot of Upper Yo Semite Fall | 0.69 | 2.67 | 3.92 | 1,114 | 5,048 |

| Forks of Trail for Top of Yo Semite Fall | 1.21 | 3.88 | 2.74 | .... | .... |

| Top of Yo Semite Fall | 0.45 | 4.33 | 2.26 | 2,550 | 6,484 |

| Eagle Meadow | 1.36 | 5.69 | 0.90 | .... | .... |

| Eagle Peak | 0.90 | 6.59 | .... | 3,818 | 7,752 |

To Snow’s Hotel, by Trail. (Between the Vernal and Nevada Falls.) |

.... |

.... |

4.63 |

.... |

.... |

| From Guardian’s Office to— | |||||

| Opposite Merced Bridge | 2.02 | 2.02 | 2.61 | .... | .... |

| Too-lool-a-we-ack (South Branch) Bridge | 0.60 | 2.62 | 2.01 | .... | .... |

| Register Rock | 0.62 | 3.24 | 1.29 | .... | .... |

| Snow’s Hotel | 1.39 | 4.63 | .... | 1,366 | 5,300 |

| If the return is made via Glacier Point, the

distance from Snow’s will be: |

.... | .... | 12.35 | .... | .... |

| Bridge, above the Nevada Fall | 0.82 | 0.82 | 11.53 | .... | .... |

| Glacier Point | 7.08 | 7.90 | 4.45 | 3,257 | 7,191 |

| Guardian’s Office | 4.45 | 12.35 | .... | .... | 3,934 |

To Glacier Point and Sentinel Dome, by Trail |

.... | .... | 5.57 | .... | .... |

| From Guardian’s Office to— | |||||

| Cook’s Hotel | 0.77 | 0.77 | 4.80 | .... | 3,934 |

| Foot of Glacier Point Trail | 0.27 | 1.04 | 4.53 | .... | .... |

| Union Point | 2.09 | 3.13 | 2.44 | 2,356 | 6,290 |

| Glacier Point | 1.32 | 4.45 | 1.12 | 3,257 | 7,191 |

| Sentinel Dome | 1.12 | 5.57 | .... | .... | .... |

| If the return is made via Snow’s Hotel, the

distances from Glacier Point are: |

.... | .... | 12.53 | .... | .... |

| Bridge, above the Nevada Fall | 7.08 | 7.08 | 5.45 | .... | .... |

| Snow’s Hotel | 0.82 | 7.90 | 4.63 | 1,366 | 5,300 |

| Guardian’s Office | 4.63 | 12.53 | .... | .... | 3,934 |

|

TABLE OF DISTANCES—Continued. | ||||||

| POINTS OF INTEREST. | Between Con- secutive Points. | From Guard- ian’s Office. | To Guardian’s Office | Altitude in feet above Yosem- ite Valley | Altitude in feet above Sea Level | |

| To Summit of South Dome, by trail. |

.... | .... | 10.00 | .... | .... | |

| From Guardian’s Office to— | ||||||

| Snow’s Hotel | 4.63 | 4.63 | 5.37 | 1,366 | 5,300 | |

| Forks of Glacier Point Trail | 0.82 | 5.45 | 4.55 | .... | .... | |

| Forks of Cloud’s Rest Trail | 2.58 | 8.03 | 1.97 | .... | .... | |

| Anderson’s Cabin | 0.60 | 8.63 | 1.37 | 3,514 | 7,448 | |

| Foot of Lower Dome | 1.00 | 9.63 | 0.37 | 3,964 | 7,898 | |

| Top of Lower Dome | 0.19 | 9.82 | 0.18 | 4,530 | 8,404 | |

| Top of South Dome | 0.18 | 10.00 | .... | 4,953 | 8,887 | |

To Summit of Cloud’s Rest, by Trail. |

.... |

.... |

11.81 |

.... |

.... |

|

| From Guardian’s Office to— | ||||||

| Snow’s Hotel | 4.63 | 4.63 | 7.18 | 1,366 | 5,300 | |

| Forks of South Dome Trail | 3.40 | 8.03 | 3.78 | .... | .... | |

| Hopkin’s Meadow | 1.26 | 9.29 | 2.52 | 4,339 | 8,273 | |

| Summit of Cloud’s Rest | 2.52 | 11.81 | .... | 5,921 | 9,885 | |

To Soda Springs and Summit of Mt. Dana by trail |

.... |

.... |

40.34 |

.... |

.... |

|

| From Guardian’s Office to— | ||||||

| Snow’s Hotel | 4.63 | 4.63 | 35.71 | 1,366 | 5,300 | |

| Forks of Cloud’s Rest Trail | 4.44 | 9.07 | 31.27 | .... | .... | |

| Top of Sunrise Ridge | 3.23 | 12.30 | 28.04 | 5,648 | 9,582 | |

| Cathedral Meadow Ridge | 5.20 | 17.50 | 22.84 | .... | .... | |

| Forks of Lake Ten-ie-ya Trail, Tuolumne Meadows | 4.14 | 21.64 | 18.70 | 4,724 | 8,658 | |

| Soda Springs | 0.90 | 22.54 | 17.80 | 4,737 | 8,671 | |

| Junction of Mt. Dana and Mt. Lyell Creeks | 0.70 | 23.24 | 17.10 | .... | .... | |

| Camping ground for Mt. Dana | 8.90 | 32.14 | 8.20 | 5,849 | 9,783 | |

| Saddle, between Mt. Gibbs and Mt. Dana | 5.20 | 37.34 | 3.00 | 7,759 | 11,963 | |

| Summit of Mt. Dana | 3.00 | 40.34 | .... | 9.376 | 13,310 | |

To Summit of Mt. Lyell, by trail. |

.... |

.... |

38.20 |

.... |

.... |

|

| From Guardian’s Office to— | ||||||

| Soda Springs | 22.54 | 22.54 | 15.66 | 4,624 | 8,558 | |

| Forks of Mt. Dana Trail | 0.60 | 23.14 | 15.06 | .... | .... | |

| Head of Tuolumne Meadows | 9.41 | 32.55 | 5.65 | 5,098 | 9,032 | |

| Summit of Mt. Lyell | 5,65 | 38.20 | .... | 9,340 | 13,274 | |

To Soda Springs, via the Eagle Peak and Lake Ten-ie-ya Trail, by trail. |

.... |

.... |

24.50 |

.... |

.... |

|

| From Guardian’s Office to— | ||||||

| Forks of Eagle Peak Trail | 4.64 | 4.64 | 19.86 | 3,219 | 7,153 | |

| Forks of Mono Trail | 1.36 | 6.00 | 18.50 | .... | .... | |

| Lake Ten-ie-ya | 10.00 | 16.00 | 8.50 | 4,120 | 8,054 | |

| Soda Springs | 8.50 | 24,50 | .... | .... | 8,671 | |

To the Summit of the Obelisk, or Mt. Clark, by trail. |

.... |

.... |

15.82 |

.... |

.... |

|

| From Guardian’s Office to— | ||||||

| Glacier Point | 4.45 | 4.45 | 11.37 | 3,257 | 7,191 | |

| Too-lool-a-we-ack Creek | 2.12 | 6.57 | 9.25 | .... | .... | |

| Camping Ground | 7.00 | 13.57 | 2.25 | 6,179 | 10,113 | |

| Summit of Obelisk | 2.25 | 15.82 | .... | 7,444 | 11,378 | |

When about midway of the avenue, which here crosses the meadow, directly in front of us, looking northerly, “Yo Semite Point” stands boldly out, the apex of which is three thousand two hundred and twenty feet above us, and the view from which, looking down into the Valley, is very impressive. This, when associated with the Giant’s Thumb, is called by the Indians, “Hum-moo,” or the Lost Arrow, and connected with which is the following characteristic

[Editor’s note: this “legend” “is almost certainly fictitious” according to NPS Ethnologist Craig D. Bates. —dea.]

Tee-hee-neh was among the fairest and most beautiful of the daughters of Ah-wah-ne. Her tall yet symmetrically rounded form was as erect as the silver firs, and as supple as the tamarack pines. The delicately tapering fingers of her small hand were, if possible, prettier than those of other Indian maidens; and the arched instep of her slender foot was as flexile as the azalea when shake by the wind. The tresses of her raven hair, unlike that of her companions, was as silky as the milkweed’s floss, and depended from her well-poised head to her ankles. Her movements were as graceful and agile as the bound of a fawn. When she stepped forth from her wigwam in the early morning, accompanied by other damsels of her tribe, to seek the mirrored river and make her unpretentious toilet, there can be but little wonder that the admiring gaze of captivated young chiefs, and the envious looks of less favored lassies, should follow her every footstep.

Then, knowing this, who could wonder at, or blame, the noble Kos-soo-kah,—the tallest, strongest, swiftest-footed, bravest and most handsome in form and face, of all the young Ah-wah-ne chiefs,—for allowing the silken meshes of devoted love to intertwine around his heart, and bring him a willing captive to her feet? Or marvel that the early spring flowers which she plucked for him were always the most redolent with perfume? Or that the wild strawberries which she picked, and the wild plums that she gathered, were ever the sweetest, because transfused by love? Then, who could censure him for not resisting the silvery sweetness of her musical voice, when she raised it in song by the evening camp-fire; or, for not withstanding the fascinations of her merry laugh, as its liquid cadences rung out at night-fall upon the air, when every note was in delicious and accordant sympathy with the pulsations of his own glad heart?

And that which filled both their souls with an intense and beatified joy was the consciousness that the tender passion was unreservedly reciprocated by each. Nothing, therefore, remained, but to select becoming presents for the parents of the bride, in accordance with Indian custom,* [* See chapter on Indian manners, customs, etc.] provide a sumptuous repast, and celebrate their auspicious nuptials with appropriate ceremonies. To do this, Tee-hee-neh and her companions would prepare the acorn bread, collect ripe wild fruits and edible herbs in liberal abundance, and garnish them with fragrant flowers; while Kos-soo-kah, pressing the best hunters of his tribe into his service, should scale the adjacent cliffs for grouse, and deer, that right royal might be the feast.

Before taking their fond and long-lingering adieus, it was agreed that Kos-soo-kah, at sunset, should go to the edge of the mountain north of Cholock,† [† The Yo Semite Fall.] and report the measure of his success to Tee-hee-neh (who was to climb to its foot to receive it), by fastening the requisite number of grouse feathers to an arrow thereby to indicate the quantity taken; and from his strong bow shoot it far out that she might see it, and watch for its falling, and thus be the first to report the good tidings of his success to her people.

After a most fortunate hunt, while his young braves were resting, preparatory to the exacting task of carrying down their game, Kos-soo-kah repaired to the point agreed upon, prepared the arrow for its tender mission, and was about to send it forth, when the edge of the cliff began to crumble away, carrying the noble Kos-soo-kah with it.

Long did the loving Tee-hee-neh wait, and longingly watch for the signal; nor would she leave her watchful post for many weary hours after darkness had settled down upon the mountain, although restless premonitions and forebodings were bringing a deeper darkness to her heart, that were intensified by the sounds of falling rock she had heard. But thinking, at last, that his ambitious wishes might have tempted him to wander farther than he had intended, and finding that his signal-arrow could not be seen in the darkness, at that very moment he might be feeling his uncertain way among the blocks of rock that strewed the Indian Cañon, down which he was to come; that possibility gave wings to her thoughts, and speed to her tripping feet, as she hurriedly picked her difficult way from ledge to ledge; passing this precipice, lowering herself rapidly over that, where a misstep must necessarily have proven fatal, until at last she reached the foot of the cliff.

Finding upon her advent there that her beloved Kos-soo-kah had not yet arrived, her anxious yearnings for his safe return, made more poignant by a kind of uncontrollable prescience, led her to the spot where he must first emerge. Hoping against hope, she could hear as well as feel the beatings of her own sad heart, as she listened through the lagging hours for the sound of his welcome footfall, or manly voice. And as she impatiently waited, pacing the hot sand backwards and forwards, she sang in the low, sweet, yet impassioned cadences peculiar to her race, that which, when translated, should be substantially rendered as follows:—

|

“Come to the heart that loves thee;

|

But, alas! finding that when the dark gray dawn of earliest morning brought not her beloved one, like a deer she sprang from rock to rock up the steep ascent, not pausing even for breath, nor delaying a moment for rest; she hastened towards the spot whence the expected signal was to be given. Tracks—his blessed tracks—could be distinctly seen, and followed to the mountain’s edge; but, alas, not one was visible to indicate his return therefrom. When she called, only the echo of her own sad voice returned an answer. Where could he be? The marks of a new fracture of the mountain disclosed the fact that a portion had recently broken off; and memory, at once, recalled the sounds that she had heard, when on the ledge below. It could not be that her heart-cherished Kos-soo-kah could have been standing there at the time of its fall! Oh! No. The Great Spirit would not be so unmindful of her burning love for him as to permit that. With agonized dread she summoned sufficient courage to peer over the edge of the cliff, and the lifeless and ghastly form of her darling was seen lying in the hollow, near that which has since been designated the Giant’s Thumb.

Spontaneously acting with a clearness and strength that despair will sometimes give, she kindled a bright fire upon the very edge of the mountain, that thereby she might telegraph her wants and wishes to those below, in accordance with a custom that every Indian learns to practice from childhood;* [* See pages 25,26.] and slow as the hours ebbed away, the entreated relief came at last, for the hoped-for recovery of her soul’s jewel, even though now sleeping in the cold embrace of death. Young sapling tamaracks were lashed endwise together, with thongs cut from the skin of the deer that were to form part of the wedding feast; and, when these were ready, Tee-hee-neh, springing forward, would permit no hands but her own to be the first to touch the beloved one. She would descend to recover him, or perish in the attempt. Finding that no amount of persuasion could change her resolve they reluctantly, yet carefully, lowered her to the prostrate form of Kos-soo-kah; and, as though strength of purpose had converted her nerves into steel, defiant of all danger, she first kissed his pale lips, then unwound the deer-skin cords from around her body, fastened them lovingly, yet firmly, to his, and gave the signal for uplifting him to the top. This accomplished, gently, yet efficiently, a reverent anxiety could be seen engraved upon the faces of those performing that kindly act, for the safe deliverance of the heroic Tee-hee-neh; but, the same undismayed fearlessness, and apparent nerve, that had enabled her to descend, did not forsake her now, and before the self-imposed task she had so unfalteringly set herself had been accomplished. Firmly fastening her foot, to prevent slipping, without other support or protection, she nervously clutched the pole with one hand, and as a signal of her wishes waved the other; and in a few moments was again at the side of her adored, though lifeless, Kos-soo-kah. Silently, tearlessly, she looked for a moment into those eyes that love had once lighted, and at the colorless lips from which she had so delectably sipped the nectar of her earthly bliss; then, noiselessly, quiveringly, sinking to her knees, she fell upon his bosom; and, when lifted by gentle hands a few moments thereafter, it was discovered that her spirit had joined that of her Kos-soo-kah, in the hunting grounds of the hereafter. She had died of a broken heart.

As the arrow that had so unexpectedly, yet so ruthlessly, brought on this double calamity, could never be found, it is believed that it was spirited away by the reunited Tee-hee-neh and Kos-soo-kah, to be sacredly kept as a memento of their undying love. The heavenward-pointed thumb, still standing there, in the hollow near which Kos-soo-kah’s body was found, is ever reverently known among all the sons and daughters of Ah-wah-nee, as Hum-moo, or “The Lost Arrow.”

On the right of Hum-Moo, or Yo Semite Point, is Indian Cañon.

|

| INDIAN CAÑON. |

It was up this cañon that the Indian prisoners escaped in 1851, as related in Chapter V, pages 68, 69; from which circumstance originated the name; and it was down this that the avenging Monos crept, when they substantially exterminated the Yo Semite tribe in 1853, as recorded in Chapter VI, pages 76, 77, and 78. This cañon, therefore, is invested with historical interest. For the purpose of enabling visitors to obtain views of the sublime scenery of the Sierras from the high ridge westerly from the crest of Yo Semite Point, and look upon the top of the Yo Semite Fall, before making its leap into the Valley, the writer had a horse-trail constructed up it, in 1870. The small stream leaping in at the side is called the Little Winkle.

Bearing to the right from this standpoint can be seen the North Dome, beneath which are the Royal Arches and Washington Tower; and, following in succession, are the Half Dome, Grizzly Peak, Mount Starr King, Glacier Point, Union Point, the Sentinel, Cathedral Peaks, Eagle Peak, Eagle Tower, and the Yo Semite Fall, all forming a glorious panorama of Valley celebrities. But, advancing toward the latter, on our right we pass the orchard, the Hutchings’ cabin (described in Chapter XI, pages 138, 139, 140 and 141), and are soon at the Yo Semite Creek Bridge, and can there see the large volume of water that forms

Looking at the full stream that is hurrying on, in the early spring at least, we can scarcely realize that all this water has just made the leap of nearly two thousand six hundred feet; or that the apparently small fall we had seen from the opposite side of the Valley, could develop into so imposing a spectacle. Noticing this on a recent occasion, when in company with a civil engineer, the inquiry was made, “About how much water do you suppose there is now rolling over the edge of that mountain yonder, judging from the size and speed of this stream?” “I will tell you this evening,” was the prompt rejoinder. At the promised time I received the following:—

When at the little red bridge which spans the stream, which I understood you to be supplied entirely by the Yo Semite Fall, this afternoon, I made a rough measurement of the quantity of water flowing, and found it to be as follows: Width 40 feet, mean depth 5 feet, mean velocity about 4 feet per second. Quantity 40x5x4=800 cubic feet per second, or about 6,000 gallons per second.

I understood you to say that you had found the width of the stream at the top of the Yo Semite Fall to be 34 feet. If the velocity there be 15 feet per second, this quantity would require a mean depth of 1 foot 7 inches.

Very respectfully yours,

Hiram F. Mills,

Civil Engineer.

Before advancing far beyond the Yo Semite Creek Bridge, let me call attention to an apparently small pine tree that stands alone, at the top of the shrub-covered slope that extends to the foot of the upper Yo Semite Fall wall, and seemingly beneath it. Now that tree, small as it appears, by careful measurement is a little over one hundred and twenty-five feet in height, by eight feet seven inches in circumference. By noticing the comparatively insignificant proportions of that tree, we may be assisted in comprehending the otherwise unrealized altitudes of these immense cliffs. The large pine growing on the ledge below that, had a circumference, at the base, of twelve feet nine inches. Hum-moo, or the Giant’s Thumb, stands prominently up and out when seen from this standpoint; and whose height is said to be two hundred and three feet above the hollow where Kos-soo-kah’s body was reputed to be found, according to the legend of the Lost Arrow.

The nearer we approach the Yo Semite Fall, the more fully do we realize its astonishing attractions. Those who content themselves by viewing this magnificent scene only at a distance, must have about the same apprehension of its impressive attraction as they would of a very beautiful woman, or handsome man, when seen about half a mile off. The same comparison will appositely apply to seeing the Vernal and Nevada Falls only from Glacier Point. It is nearness that places us in appreciative communion with Nature and her manifold and unspeakable glories. I have accompanied hundreds, aye, thousands, to the foot of the Lower Yo Semite Fall, and this, without an exception, has been the spontaneous confession of every one. So that every step that we take after crossing the Yo Semite Creek Bridge puts us into closer relationship with the impressive majesty of this wonderful fall. “How it grows upon us,” is a most frequent ejaculation that is born of apprehensive and appreciative feeling. How we watch the bold leap that it is making over the cliff, more than two thousand five hundred feet above our heads, and follow the vaulting masses of its rocket-shaped and foaming waters with the eye, down to the seething caldron into which it bounds, at the base of the upper fall; its eddying mists fringed by the sun with iridescent colors, that are constantly changing and reforming. At the right of the fall, just below its crest, a dark mass of shadow reveals the portrait of the “Gnome of the Yo Semite,” with his badge of rank hanging across the shoulder.

|

| Photo by C. L. Weed. |

| VALLEY FORD OF THE YO SEMITE. |