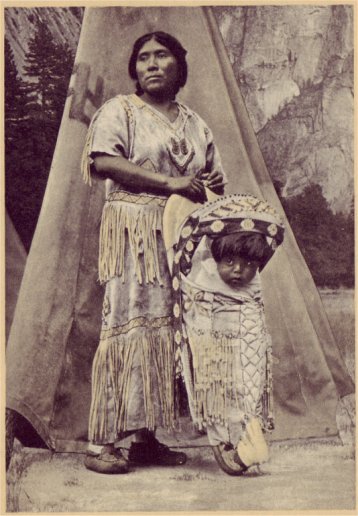

Yosemite Indians are building in Yosemite a new village in replica of those of their forefathers

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Lights & Shadows > Early Occupants—The Indians >

Next: Discovery of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Origin of Yosemite

The Indians

Out of the forest, and onto the Yosemite stage, step the first actors, the Indians. Not knowing a Yosemite Valley existed, there at their feet they beheld for the first time this unbelievable valley, with its sheer, sculptured cliffs of granite, its gleaming river and broad meadows, its forests and its snow-capped domes. What a moment in human history!

And yet, this stupendous scenery which was to stir so greatly the souls of the white men who came later, probably made small impression upon them. With a grunt or two, no doubt, signifying “good, safe, resting spot,” these first claim-stakers descended, and soon the smoke from many round houses was wreathing upward, declaring the first human occupancy of Yosemite Valley, which the Indians knew as Ahwahnee—“deep, grassy valley.”

Here this tribe of Indians lived and flourished for many generations. Then came a famine, and the black sickness, which all but exterminated these people. Those few who survived, believing the Great Spirit to have visited his wrath upon them, fled, many never to return. They scattered throughout California and Nevada, many of them attaching themselves to the Mono and Pai-ute tribes.

The father of Chief Tenaya was one of these Ahwahneechees who fled from Yosemite. He married a Mono maiden of the tribe with whom he sought refuge. When young Tenaya grew to manhood, he was persuaded by the urgings of an aged medicine man of his father’s tribe to gather together the descendants of the Ahwahneechees and to return with them to their former home. The old patriarch prophesied that as long as Tenaya retained possession of Ahwahnee, his band would increase in numbers and become powerful. If he befriended those who sought his protection, no other tribe would come to the valley to make war upon him or attempt to drive him from it. Furthermore, the old counselor warned him against the horsemen of the lowlands, the early Spanish Californians, and declared that should they enter Ahwahnee his tribe would soon

PHOTO BY F. J. TAYLOR

[click to enlarge]

Yosemite Indians are building in Yosemite a new village in replica of those of their forefathers |

Tenaya’s band, augmented by refugees and outcasts from the other tribes, became known as the Yosemites, signifying “Grizzly Bears.” There are several explanations of the choice of this name. One legend relates that a warrior of this tribe, armed only with the dead limb of a tree, in a surprise encounter fought and killed a grizzly bear. Dragging himself back to the village, bleeding and exhausted, he told of his battle. Henceforth, he was deferentially referred to as Yosemite, Killer of the Grizzly Bear. The name was handed down to his descendants, and was finally adopted by the tribe. The more likely explanation is, however, that at that time this region abounded in grizzly bears, and the likeness between the bear and his fierce and ruthless Indian hunter suggested itself to the less warlike tribes, who referred to the Awahneechees somewhat in derision as the Yosemites, or Grizzlies.

Came the gold rush of ’49 and ’50, and the stampede of the miners to the slopes of the Sierra Nevada. Quite naturally the Indians resented this overrunning of their peaceful valleys, the destruction of their chief staple of diet, the acorns, by the hogs and donkeys of the white men, the plowing under of great fields of clover and tender grasses to make way for the white men’s crops. Friction resulted. The Indians evened up scores by stealing the cattle and horses of the intruders, and in many instances they plundered, burned, and murdered, in their efforts to drive the white men out.

There followed the Indian wars of 1851, at which time the Indians were effectually hunted out and captured by the United States volunteer troops, and brought down from their mountains into the reservations established for them by the Government. Tenaya and his band resisted to the last, but they too were finally subdued and brought in to the reservation near Fresno. They were later paroled and allowed to go back to their mountains, upon the solemn agreement with old Chief Tenaya not to molest the white men further.

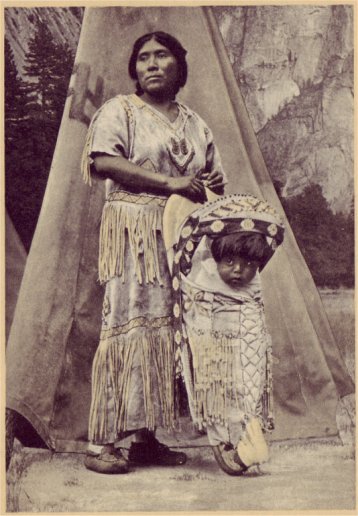

PHOTO BY J. V. LLOYD

[click to enlarge]

Indian Field Day, when all the Indians around Yosemite gather in the Valley for rodeo sports |

The Government exacted retribution for this, and again sent troops into the Valley. While the five self-confessed murderers were taken, and summarily shot, Chief Tenaya and his people escaped over the mountains and took refuge with the Monos.

After an extended stay with their friendly and hospitable neighbors, they returned once more to Ahwahnee. But with them returned some of their hosts’ horses, and for this gross breach of etiquette, the Monos, in righteous wrath, promptly returned the Ahwahneechees’ call, in head feathers and war paint. Finding their erstwhile guests stuffed and stupid with feasting on the stolen horses, the Monos took their revenge, wiping out all but a handful of the Yosemite tribe.

One could have wished a more glorious end to so dramatic a career as old Chief Tenaya’s, but the pitiless fact is that here in his beloved Ahwahnee he met his death by a rock hurled by an incensed Mono neighbor.

Today there are still to be found in Yosemite descendants of this fearless band that once roamed and owned the Valley. But each year sees their number decreased. Encouraged by the Government which once drove their forefathers out, they are rebuilding a village on the very site they occupied when discovered by the Mariposa Battalion on its first entry into the Valley. Until recently, their acorn caches were still standing in the Valley, and their hollowed stones for grinding acorns are yet to be found. Each year they hold here their annual Indian Field Day, at which time the Mono Indians from Nevada, and Indians from the plains below, gather in Yosemite and participate in contests of various kinds, bringing with them their baskets and beadwork, their papooses and their bobbed-hair flapper Pocahontases.

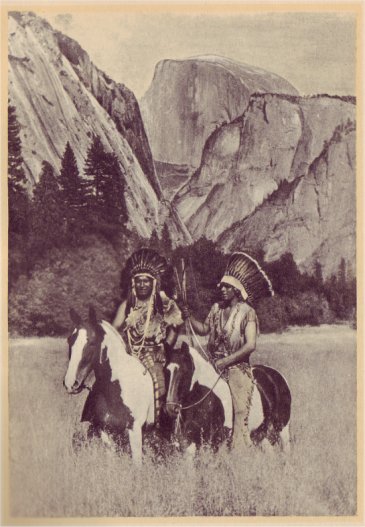

PHOTO BY CHAS. M. HILLER

[click to enlarge]

Leevining Canyon, on the Tioga Road, is the land of magnificent distances |

Next: Discovery of Yosemite • Contents • Previous: Origin of Yosemite

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/lights_and_shadows/indians.html