By Schwartz

Mariposa in the ’Fifties

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > 100 Years in Yosemite > Mariposa Hills >

Next: White Chief of the Foothills • Contents • Previous: Discovery

By Schwartz Mariposa in the ’Fifties |

|

|

|

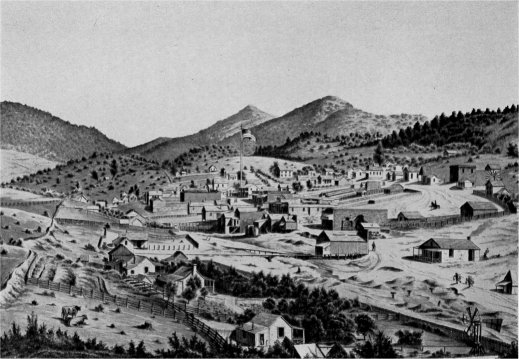

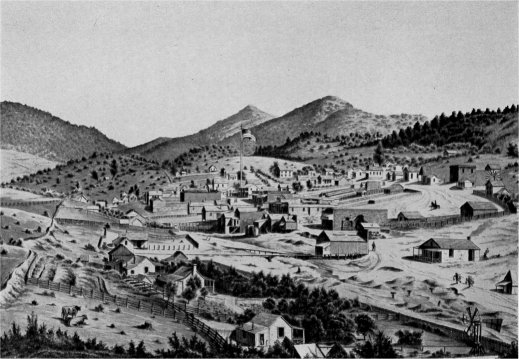

| Woodcut from the first edition (1931) |

Following the significant work of the early overland fur traders there came a decade of immigration of bona fide California settlers. The same forces that led the pioneer across the Alleghenies, thence to the Mississippi, and from the Mississippi into Texas, explain the coming of American settlers into California. Hard times in the East stimulated land hunger, and California publicity agents spread their propaganda at an opportune time. Long before railroads, commercial clubs, and real estate interests began to advertise the charms of California, its advantages were widely heralded by the venturesome Americans who had visited and sensed the possibilities of the province. The press of the nation took up the story, and the people of the United States were taught to look upon California as a land of infinite promise, abounding in agricultural and commercial possibilities, full of game, rich in timber, possessed of perfect climate, and feebly held by an effeminate people quite lacking in enterprise and disorganized among themselves.

The tide of emigration resulting from this painting of word pictures began its surge in 1841 with the organization of the Bidwell-Bartleson party. Other parties followed in quick succession, and many of the pioneer fur hunters of the preceding decade found themselves in demand as guides. The settlers came on horseback, in ox wagon, or on foot, and with the men came wives and children. They entered the state by way of the Gila and the Colorado, the Sacramento, the Walker, the Malheur and the Pit, and the Truckee. Some journeyed to the Mono region east of Yosemite and either struggled over difficult Sonora Pass just north of the present park or tediously made their way south to Owens River and then over Walker Pass. The Sierra Nevada experienced a new period of exploration, and California took a marked step toward the climax of interest in her offerings.

This pre-Mexican War, pre-gold-rush immigration takes a prominent place in the history of the state, and the tragedy and success of its participants provide a story of engrossing interest. They had forced their slow way across the continent to find a permanent home beside the western sea, and their arrival presaged the overthrow of Mexican rule in California. The Mexican, Castro, stated before an assembly in Monterey: “These Americans are so contriving that some day they will build ladders to touch the sky, and once in the heavens they will change the whole face of the universe and even the color of the stars.”

In one of the parties of settlers was a man of no signal traits, who, by a chance discovery, was to set the whole world agog. This was James W. Marshall, an employee of John A. Sutter of the Sacramento: On January 24, 1848, he found gold in a millrace belonging to Sutter. About a week later the inevitable took place. California became a part of the United States.

The news of the gold discovery spread like wildfire, and by the close of 1848 every settlement and city in America and many cities of foreign lands were affected by the California fever. Gold seekers swarmed into the newly acquired territory by land and by sea. The overland routes of the fur trader and the pioneer settler found such a use as the world had never seen. From the Missouri frontier to Fort Laramie the procession of Argonauts passed in an unbroken stream for months. Some 35,000 people traversed the Western wilderness and 230 American vessels reached California ports in 1849. The western slope of the Sierra from the San Joaquin on the south to the Trinity on the north was suddenly populous with the gold-mad horde. On May 29, the Californian of Yerba Buena issued a notice to the effect that its further publication, for the present, would cease because its employees and patrons were going to the mines. On July 15 its editor returned and published an account of his personal experiences as a gold seeker. He wrote: “The country from the Ajuba [Yuba] to the San Joaquin, a distance of about 120 miles, and from the base toward the summit of the mountains . . . about seventy miles, has been explored and gold found on every part.”

By 1849 the Mariposa hills were occupied by the miners, and the claims to become famous as the “Southern Mines” were being located. Jamestown, Sonora, Columbia, Murphys, Chinese Camp, Big Oak Flat, Snelling, and Mariposa, all adjacent to the Yosemite region, came to life in a day. Stockton was the immediate base of supply for these camps.

The history of Mariposa is replete with fascinating episodes, May Stanislas Corcoran, a daughter of Mariposa, has supplied the Yosemite Museum with a manuscript entitled “Mariposa, the Land of Hidden Gold,” which comes from her own accomplished pen. From it the following brief account is abstracted as an introduction to the beginnings of human affairs in the Mariposa hills.

In 1850, Mariposa County occupied much of the state from

Tuolumne County southward. A State Senate Committee on

County Subdivision, headed by P. H. de la Guerra, determined

its bounds, and a Select Committee on Names, M. G. Vallejo,

Chairman, gave it is name—a name which was first applied by

Moraga’s party in 1806 to Mariposa Creek.1

[

1

The first legislature of the state appointed a committee to report on the

derivation and definition of the names of the several counties of California. The

report is dated April 16, 1850 and from it is quoted the following:

“In the month of June, 1806 (in one of their yearly excursions to the valley of

the rushes—Valle de los Tulares—with a view to hunt elks), a party of Californians

pitched their tents on a stream at the foot of the Sierra Nevada, and whilst there,

myriads of butterflies, of the most gorgeous and variegated colors, clustered on

the surrounding trees, attracted their attention, from which circumstance they

gave the stream the appellation of Mariposa. Hence Mariposa River, from which

the county (also heavily laden with the precious metal) derives its poetical name.”

]

Gradually through

the years, the original expansive unit was reduced by the creation

of other counties—Madera, Fresno, Tulare, Kings, and

Kern, and parts of Inyo and Mono counties.

Agua Fria was at first the county seat, but even in the beginning the town of Mariposa was the center of the scene of activity. Four mail routes of the Pony Express converged upon it. Prior to the arrival of Americans, the Spanish Californians had scarcely penetrated the Sierra in the county, but these uplands were well populated with Indians. One of the strongest tribes, the Ah-wah-nee-chees, lived in the Deep Grassy Valley (Yosemite) during the summer months and occupied villages along the Mariposa and Chowchilla rivers in the winter.

[Editor’s note: the correct meaning of Ahwahnee is “(gaping) mouth.” See “Origin of the Place Name Yosemite”—dea.]

Mariposa proved to be the southernmost of the important southern mines. Of the people who were drawn to it during the days of the gold rush, many were from the Southern States. They brought “libraries . . . horses from Kentucky . . . silk hats, chivalry, colonels, and culture from Virginia; and from most of the states that later became Confederate, lawyers, doctors, writers, even painters—miners all. . . . Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New York, and Europe also sent representatives, and there were Mexican War veterans, such as Jarvis Streeter, Commodore Stockton, Colonel Frémont, and Capt. Wm. Howard.” By Christmas, 1849, more than three thousand inhabitants occupied the town of Mariposa, which extended from Chicken Gulch to Mormon Bar.

In February, 1851, a remarkable vein of gold was discovered in the Mariposa diggings, first designated as the “Johnson vein of Mariposa,” and extensive works were developed from Ridley’s Ferry (Bagby) to Mount Ophir. These properties were acquired by a company having headquarters in Paris, France, which became known as “The French Company.”

The Frémont Grant, also known as the Rancho Las Mariposas, was a vast estate of 44,386 acres of grazing land in the Mariposa hills, which Colonel J. C. Frémont acquired by virtue of a purchase made in 1847 from J. B. Alvarado. It was one of several so-called “floating grants.” After gold was discovered in the Mariposa region in 1848, Frémont “floated” his rancho far from the original claim to cover mineral lands including properties already in the possession of miners. The center of Frémont’s activities was Bear Valley, thirteen miles northwest of Mariposa. Lengthy litigations in the face of hostile public sentiment piled up court costs and lawyer fees. However, the United States courts confirmed Frémont’s claims, and other claimants, including the French Company, lost many valuable holdings. Tremendous investments were made in stamp mills, tunnels, shafts, and the other appurtenances related to the mining towns as well as to the mines which Frémont attempted to develop.

In spite of its phenomenal but spotty productiveness, the Frémont Grant brought bankruptcy to its owner and was finally sold at sheriff sale. The town of Mariposa, which was on Frémont’s Rancho, became the county seat in 1854, and the present court house was built that year. The seats and the bar in the courtroom continue in use today, and the documents and files of the mining days still claim their places in the ancient vault. They constitute some of the priceless reminders of a dramatic period in the early history of the Yosemite region. In these records may be traced the transfer of the ownership of the Mariposa Grant from Frémont to a group of Wall Street capitalists. These new owners employed Frederick Law Olmsted as superintendent of the estate. He arrived in the Sierra in the fall of 1863 to assume his duties at Bear Valley. The next year he was made chairman of the first board of Yosemite Valley commissioners, so actively linking the history of the Mariposa estate with the history of the Yosemite Grant. Olmsted continued his connection with the Mariposa Grant until Aug. 31, 1865, at which time he returned to New York and proceeded to distinguish himself as the “father” of the profession of landscape architecture.

His son, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., born July 24, 1870, has continued in the Olmsted tradition. As an authority on parks, municipal improvements, city planning and landscape architecture, and the preservation of the American scene he has exerted a leadership comparable to his father’s pioneering. He has entered the Yosemite picture as National Park Service collaborator in planning and as a member of the Yosemite Advisory Board, to which organization he was appointed in 1928.

One of the few members of the small army of early miners in the Mariposa region who left a personal record of his experiences was L. H. Bunnell. His writings provide most valuable references on the history of the beginning of things in the Yosemite region. He was present in the Mariposa hills in 1849, and from his book, Discovery of the Yosemite, we learn that Americans were scattered throughout the lower mountains in that year. Adventurous traders had established trading posts in the wilderness in order that they might reap a harvest from the miners and Indians.

James D. Savage, the most conspicuous figure in early Yosemite history, whose life story, if told in full, would constitute a valuable contribution to Californian, was one of these traders. In 1849 he maintained a store at the mouth of the South Fork of the Merced, only a few miles from the gates of Yosemite Valley. Now half a million people each year hurry by this spot in automobiles; yet no monument, no marker, no sign, indicates that the site is one of the most significant, historically, of all localities in the region. It was here that the first episode in the drama of Yosemite Indian troubles took place. The story of the white man’s occupancy of the valley actually begins at the mouth of this canyon in the Mariposa hills.

Next: White Chief of the Foothills • Contents • Previous: Discovery

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/one_hundred_years_in_yosemite/mariposa.html