THE SOUTH FARALLONE ISLAND, FROM THE BIG ROOKERY, LOOKING EAST.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Scenes of Wonder & Curiosity > The Farallone Islands >

Next: San Francisco • Contents • Previous: Mount Shasta

THE SOUTH FARALLONE ISLAND, FROM THE BIG ROOKERY, LOOKING EAST. |

This is the name of a small, group of rocky islands, lying in the Pacific Ocean, about twenty-seven miles west of the Golden Gate, and thirty five miles from San Francisco. These islands have become of some importance, and of considerable interest, on account of the vast quantity of eggs that are there annually gathered, for the California market; these eggs having become an almost indispensable article of spring and summer consumption, to many persons.

By the courtesy of the Farallone Egg Company, through their President, Captain Richardson, the schooner Louise, Captain Harlow, was placed at our service, for the purpose of visiting them; and, in company with a small party of friends, we were soon upon the deep green brine, ploughing our way to the “Isles of the Ocean.”

Bright and beautiful slept the morning, as a light breeze, blowing gently from the mountains, filled our sails, and sped us on our way through

There are probably but few persons, comparatively, who have ever passed through this entrance to the fine Bay of San Francisco, that are familiar with the origin and meaning of the name, the popular idea being that its name was suggested by the staple mineral of the country—gold. This is incorrect, as it was called “The Golden Gate” before the precious metal was discovered; and the first time that it was used, most probably, was in a work entitled “A Geographical Review of California,” with a relative map, published in New York, in the month of February, 1848, by Colonel J. C. Fremont; and as gold was discovered on the 19th of January preceding, in those days it would have been next to impossible for the news to have reached the office of publication of that work, in time for the name to be given, from such a cause.

The real origin of the name was from the excessively fertile lands of the interior—especially of those adjacent to the Bay of San Francisco. There may have been some “Spiritual Telegrams” sent from California (!) to the parent of the name, telling him of the glorious dawn of a Golden Day that had broke upon the world at Sutter’s Mill, Coloma and that such a name would be the magic charm to millions of men and women in every quarter of the world, in the Golden Age about to be inaugurated. We do not say that it was so. We do not wish the reader to believe it, as our opinion, that it was thus originated; but in this age of spiritual darkness—we allude to the limited knowledge of mental phenomena—we start the supposition, in hope that it may stir up the spirit of inquiry. This one thing is certain, that from whatever source the name “Golden Gate” may have originated, it was most happily suggestive in its character. Having dwelt at some length upon the name, we will now more briefly describe the spot.

That it is the gateway or entrance to the magnificent harbor of San Francisco, every one is well aware. The centre of this entrance is in longitude 122° 30' W. from Greenwich. On the south of the entrance, is Point Lobos (Wolves’ Point), on the top of which is a telegraph station, from whence the tidings of the arrival of steamers and sailing vessels are sent to the city. On the north side, is Point Bonita (Beautiful Point), readily recognized by a strip of land running out toward the bar, on the top of which is a lighthouse, that is seen far out to sea, on a clear day,

CLIPPER SHIP CROSSING THE BAR OUTSIDE THE ENTRANCE OF THE BAY OF SAN FRANCISCO. |

In front of the entrance is a low, circular sand-bar, almost seven miles in length, but on which is sufficient water, even at low tide, to admit of the largest class of ships crossing it in safety—except, possibly, when the wind is blowing from the north-west, west, or south-east; at such a time, it is scarcely safe for a very large vessel to cross it at low tide.

From Point Bonita to Point Lobos, the distance is about these and a half miles; and between Fort Point and Lime Point (just opposite each other), the narrowest part of the channel, and “The Golden Gate” proper, it is one thousand seven hundred and seventy-seven yards. Here the tide ebbs and flows at the rate of about six knots an hour.

To the dwellers of a seaport city, there is music in the ever restless waves, as they murmur and break upon the shore; but to sail upon the broad, heaving bosom of the ocean, gives an impression of profoundness and majesty, that, by contrast, becomes a source of peaceful pleasure; as change becomes rest to the weary. There is a vastness, around, above, beneath you, as wave after wave, and swell after swell, lifts your tiny vessel upon its seething surface, as though it were a feather—a floating atom upon the broad expanse of waters. Then, to look into its shadowy depth, and feel the sublime language of the Psalmist: “O Lord, how manifold are thy works! in wisdom hast Thou made them all: the earth is full of thy riches. So is this great and wide sea, wherein we things creeping innumerable, both small and great beasts. These wait all upon Thee: that Thou mayest give them their meat in due season. Thou openest thy hand, they are filed with good. Thou hidest thy face, they are troubled.” “They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters: these see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep. He commandeth, and raiseth the stormy wind, which lifteth up the waves thereof. He maketh the storm a calm, so that the waves thereof are still.”

“Oh, that men would praise the Lord for his goodness, for his wonderful works to the children of men!”

Object after object became distant and less, as we left them far, far behind us.

“Yonder blows a whale!“ cries one.

“Where?”

“Just off our larboard bow.”

“Oh! I see it—but”——

“But! what’s the matter?”

“Oh! I feel so sea-sick.”

“Well, never mind that; look up, and don’t think about it.”

“Oh—I can’t—I must.”——

Reader, were you ever sea-sick? If your experience enables you to answer in the affirmative, you will sympathize somewhat with the poor subject of it. Yonder may be this beauty, and that

ENCHANTED WITH THE DELIGHTFUL PROSPECT OFF THE BAR. |

“How are you now?” kindly asks our good-natured captain, of the one and the other.

“Ah! I thank you; I am better.”

“Here, take a cup of nice hot coffee.”

“No; I thank you.”

The mere mention of any thing to eat or drink is only the signal for a renewal of the sickness.

“Thank goodness! I feel better,” says one, after a long spell of sickness and quiet.

“So do I,” says another; and, just as the “Farallones” me in sight, fortunately, all are better.

SOUTH-EAST VIEW OF THE FARALLONE ISLANDS. |

Now the air is literally filled with birds—birds floating above us, all birds all around us, like bees that are swarming, we thought the whole group of islands must have been deserted, and that they had poured down in myriads, on purpose to intercept our landing, or “bluff us off;” but, as the dark, weather-beaten furrows, and the wave-washed chasms, and the wind-swept masses of rock, rose more defined and distinct before us as we approached, we concluded that they must have abandoned the undertaking— for upon every peak sat a bird, and in every hollow a thousand; but, looking around us again, the number, apparently, had increased rather than diminished, and the more them seemed to be upon the islands the greater the increase round about us—so that we concluded our fears to be entirely unfounded.

The anchor is dropped in a mass of dealing foam, on the southeast and sheltered side of the islands, and in a small boat we reach the shore, thankful, after this short voyage, to feel our feet standing firmly on terra firma.

Looking at the wonders on every side, we were astonished that we had beard so little about them, and that a group of islands like these should lie within a few hours’sail of San Francisco, yet not be the resort of nearly every seeker of pleasure, and every lover of the wonderful.

It is like one vast menagerie. Upon the rocks adjacent to the sea repose in easy indifference, thousands—yes, thousands—of sea lions (one species of the seal), that weigh from two to five thousand pounds each. As these made the loudest noise, and to us were the most curious, we paid them the first visit. When we were within a few yards of them the majority took to the water, while two or three of the oldest and largest remained upon the rock, “standing guard” over the young calves, that were either at play with each other, or asleep at their side. As we advanced, these masses of “blubber” moved slowly and clumsily toward us, with their mouths open, and showing two large tusks that were standing out from their lower jaw, by which they gave its to understand that we had better not disturb the repose of the juvenile “lions,” nor approach too near, or we might receive more harm than we expected or wished. But the moment we threw at them a stone, they would scamper off, and leave the young lions to the mercy of their enemies. We advanced and took hold of one, to try if the sight of their young being taken away would tempt them

[Man in a tight place.] |

All of these animals are very jealous of their particular rock, where, in the sun, they take their siesta, and although we remained upon some of these spots for a considerable length of time, while their usual tenants were swimming in the sea, and perhaps had become somewhat uneasy, they were not allowed to land on the territory of another.

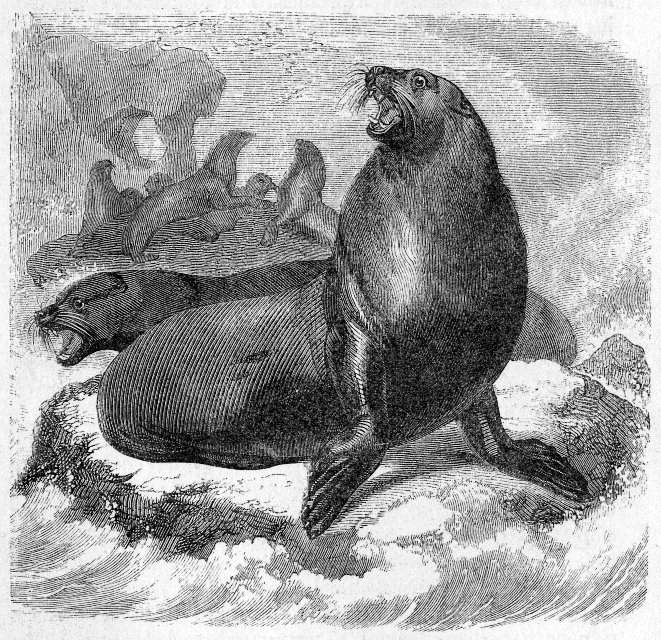

SEA LIONS AND THEIR YOUNG. |

They keep up an incessant short, moaning cry, that sounds like yoi hoey, yoi hoey, in about the same key as the bray of a mule.

Most of these young seals are of a dark mouse color, but the old ones are of a light and brightish brown about the head, and gradually become darker toward the extremities, which are about the same color as the young calves. Most of the male and young female seals leave these islands during the months Of October or November—and generally all go at once—returning in April or May the following spring, while the older females remain here nearly alone throughout the winter—a rather ungallant proceeding on the part of the males.

There are several different kinds of seal that pay a short visit hem at different seasons of the year, one of the most beautiful of which is the hair seal of the Pacific (Phoco jubata).

THE HAIR SEAL OF THE PACIFIC. |

This seal, with which the coast of California abounds, is by no means rare, as almost all the coasts in high southern and northern latitudes abound with it. “To the Laplander, it is meat, drink, clothing, etc. To the Indians of Behring’s Straits and Kamschatka it is most valuable; in fact, they could hardly exist without it. Far away in those inhospitable regions, where e winter reigns three-fourths of the year, no timber can be obtained sufficiently large to build a canoe; but with a few seal-skins and a little whale-bone, the Indian will construct one of the most perfect life-boats in the world. In this he will fearlessly venture miles from land to catch fish and seals, aye, End even the whale. These canoes are difficult to manage to those who are unacquainted with them. It requires no small degree of practice, even to the Kamschatkan, in a rough sea, to keep such a boat alive. He is not allowed to marry unless he have the ability of so making and guiding them. Indeed, his canoe is all to him—his house, his clothes, his furniture, his food—for without it, his shores, prolific in fish, would be useless.

“Its countenance bears the impress of great sagacity; its full, round, beautiful eye indicates even an intelligence rarely to be found in any other inhabitant of the waters. This was remarked by the ancient historian, Pliny. He gives an amusing account of one that was easily taught to perform certain tricks. It would salute visitors freely, and would answer to its name when called. F. Cuvier narrates of one that he saw that was made to stand erect on its tail, and hold a staff between its flippers like a sentinel on duty. It would tumble heels over head when desired, give a flipper to be shaken, and present its lips for its keeper’s kiss.

“Captain Russell, the assiduous traveller and explorer of the seaboard resources of California, informed us that it is most amusing sometimes to see their contests with the Coast Indians. These fellows skulk behind the rocks adjacent to some gently-sloping sand-banks, and when the shoal has become dry by the receding tide, they front the body and interpose their return to the water, each selecting as his prey the biggest and most powerful. Catching hold of the tail-flipper, the animal scuffles along the sand, dragging along after him the Indian, who, with a tight grip, follows, until, by ploughing a deep furrow with his feet, leaning back, and with all his strength resisting the powerful progress of the animal, until both come to a dead stand; the animal’s side-flippers are then tied by another party, and the poor beast thus easily becomes his prey. He often, he says, remonstrated in vain against their barbarous cruelty of preparing them for food, or for blubber. A huge fire is made in a large flat hole in the ground, and the poor besets are hurled in and roasted alive. “We have no other way,” said they, “of singeing or scorching off the hair. If they were put in dead, we should have to get in the fire ourselves to turn them, but being alive, they spare us the trouble, and turn themselves, when one side is singed sufficiently.”

“The whole tribe possesses remarkable peculiarities of respiration and circulation of blood. The interval between their respirations is very long. A full-grown animal can remain under water, without requiring a fresh inspiration, for upwards of half an hour. They can open and close at pleasure, for these purposes, their valvular nostrils in a surprising degree, eating their food all the time underwater with perfect enjoyment. Their breathing is remarkably slow, and very irregular. After opening the nostrils and making a long expiration, the creature inhales air by a long inspiration, and just before diving, closes its nostrils as tight as any mechanical valve. In confinement, they have been observed to remain asleep, with the head under water, for an hour at each time, without any fresh inhalation of air. Naturalists account for this power by the animal’s possessing a great venous canal in its liver, which assists it in diving, so that their respiration is somewhat independent of the circulation of the blood.

“One of these animals was exhibited in Adams’ Museum, San Francisco, and was in excellent condition, exceedingly tame, and very submissive to its keeper. It seemed to enjoy the music, appearing to listen to it with some pleasure. This is not to be wondered at, as the hearing of this class of animals is very acute; and well attested instances are by no means rare, of many, even in a wild state, being attracted by the sound of a flute, or a horn; rising up to the surface to enjoy it the more, and sinking immediately the sounds are discontinued. The brain in the seal is very large, and its whiskers we connected with nerves of immense size, serving almost every purpose of sensation.”

The Russians formerly visited these islands, for the purpose of obtaining oil and skins, and several places can be yet seen where the skins were stretched and dried.

The birds which are by far the most numerous, and, on account of their eggs, the most important, are the Murre, or Foolish Guillemot, which we found here in myriads, surmounting every rocky peak, and occupying every small and partially level spot upon the islands. Here it lays its egg, upon the bare rock, and never leaves it, unless driven off, until it is hatched; the male taking its turn, at incubation, with the female—although the latter is most assiduous.

THE MURRE, OR FOOLISH GUILLEMOT. |

When the young are old enough to emigrate, the murres; take them away in the night, lest the gulls should eat them; and as soon as the young reach the water, they swim at once. Some idea may be formed of the number of these birds, by the Farallone Egg Company having, since 1850, brought to the San Francisco market between three and four millions of eggs.

On this coast these birds are numerous, in certain localities, from Panama to the Russian possessions. On the Atlantic, they are found from Boston to the coast of Labrador; differing but very little in color, shape, or size.

THE MURRE’S EGG—FULL SIZE. |

It is a clumsy bird, almost helpless on land, but is at home on the sea, and is an excellent swimmer and diver, and is very strong in the wings. Their eggs are unaccountably large, for the size of the bird, and “afford excellent food, being highly nutritive and palatable—whether boiled, roasted, poached, or in omelets.” No two eggs are in color alike.

THE TUFTED PUFFIN. |

The bird of most varied and beautiful plumage, on the islands, is the Mormon Cirrhatus, or Tufted Puffin; and, although they are rather numerous on this coast, they are very scarce elsewhere.

In addition to the murre, puffin, and gull, already mentioned, there are pigeons, hawks, shag, coots, etc., which visit here during the summer, but, with the exception of the gull and shag, do not remain through the winter.

The horned-billed guillemot has been seen and caught here, but it is exceedingly rare.

Now, with the reader’s permission, we will leave the birds and animals—at least if we can—and take a walk up to the lighthouse, at the top of the island, three hundred and fifty-seven feet above the sea. A good pathway has been made, so that we can ascend with ease. If you find that we have not left the birds, nor the birds left us, but that, at every step we take, we disturb some, and pass others, and that thousands are flying all around us, never mind—when we reach the top we shall forget them, at least for a few moments, to strain our eyes in looking toward the horizon, and seeking to catch a glimpse of some distant object. Yonder, some eight miles distant, are the “North Farallones,” a very small group of rocks, and not exceeding three acres in extent— but, like this, they are covered with birds.

Now let us enter the lighthouse, and, under the guidance of Mr. Wines, the superintendent, we shall find our time well spent in looking at the best lighthouse on the Pacific coast. Everything is bright and clean, its machinery in beautiful order, and working as regular in its movements as a chronometer.

The wind blows fresh outside, and secretly you hope the lighthouse will not blow over before you get out. Here, too, you can see the shape of the island upon which you stand, mapped out upon the sea below.

Let us descend, wend our way to the “West End,” and pass through the living masses of birds, that stand, like regiments of white-breasted miniature soldiers, on every hand—and it might be well to take the precautionary measure of closing our ears to the perpetual roaring, and loud moaning of the sea lions, for their noise is almost deafening. A caravan of wild beasts is nothing, in noise, to those.

Let us be careful, too, in every step that we take, or we shall place our foot upon a nest of young gulls, or break eggs by the dozen, for they are everywhere around us. We soon reach the side of the “Jordan,” as a small inlet is called, and across which we call step at low tide, but which is thirty feet wide at high water. To cross it, however, a rope and pulley is your mode of conveyance; so hold tight by your hands, and you’ll soon get across. Safely over, let us make our way for a glimpse of the West End View, looking East.

VIEW FROM WEST END, LOOKING EAST. |

This is a wild all beautiful scene. The sharp-pointed rocks are standing boldly out against the sky, and covered with birds and sea lions. A heavy surf is rolling in, with thundering hoarseness, and as the wild waters break upon the shore, they resemble the low, booming sound of distant thunder; while the white spray curls over, and falls with a hissing splash upon the rocks, and then returns again to its native brine; while, swimming in the boiling sea, amid the foam and rocks, just peering above the water, are the heads of scores of sea lions. Let us watch them for a moment. Here comes one noble looking old fellow, who rises from the water, and works his way, slowly and clumsily, toward the young which lie high and dry, sleeping in the sun, or are engaged lazily scratching themselves with their hind claws; and, although we are very near them, they lie quite unconcerned, and innocent of danger. Not so the old gentleman, who has just taken his position before as, as sentry. Experience has doubtless taught him that such looking animals as we are behave no better no better than we should do, and be knows it!

There are water-washed caves, and deep fissures between the rocks, just at our right; and in the distance is a large arch, not less than sixty feet in height, its top and sides completely covered with birds. Through the arch, you can see a ship, which is just passing.

Now let us go to the “Big Rookery,” lying on the north-west side of the island.

This locality derives its name from the island here forming a hollow, well protected from, the winds; and being less abrupt than other pieces, is on that account a favorite resort of myriads of sea fowl, who make this their place of abode, and where vast numbers of young are raised. If you walk among them, thousands immediately rise, and for a few moments darken the air, as though a heavy cloud had just crossed and obscured the sunlight upon your path. But few persons who have not seen them can realize the vast numbers that make this their home, and which are here, there, and everywhere, flying, sitting, and even swimming, upon the boiling and white-topped surge among the seals.

Here, as elsewhere, there are thousands of seals, some are suckling their calves, some are lazily sleeping in the sun, others are fishing, some are quarrelling, others am disputing possession, and yonder, just before us, two large and fierce old fellows are engaged in direful combat with each other—now the long tusks of the one are moving upward to try to make an entrance beneath the jaw of the other—now they are below—now there is a scattering among the swimming group that have merely been looking on to see the sport, for the largest has just come up among them, and they are afraid of him. Now appears his antagonist, his eyes rolling with maddended frenzy, they again meet—now under, now over—fierce wages the war, hard goes the battle, but at last the owner of the head, already covered with scales, has conquered, and his discomfitted enemy makes his way to the nearest rock, and there lies panting and bleeding; but he may not rest here, for the owner of that claim is at home and has possession, and without any sympathy for his suffering and unfortunate brother, he orders him off, although “only a squatter,” and he again takes to the sea in search of other quarters.

From this point we get in excellent view of the lighthouse, and the residence of the keepers. Everywhere them is beauty, wildness sublimity. Let us not linger too long here, although weeks could be profitably spent in looking at the wonders around us, but let us take a hasty glance at the View from the North Landing.

VIEW FROM THE NORTH LANDING, LOOKING NORTH. |

Here there is a fine estuary, where, with a little improvement, small schooners can enter at any season of the year, and where the oil and other supplies are landed for the lighthouse. Like the other views, it is singular and wild—each eminence covered with birds, each sea-washed rock occupied by seals, and the air almost darkened by the sea gulls skimming backward and forward, like swallows, and by the rapid and apparently difficult flight of the murres.

From this point we can get an, excellent view of the North Farallones, that, in the dim and shadowy distance, are looming up their dull peaks just above the restless and swelling waves. From the sugar-loaf shaped peak, and the singularly high arch, and bold, rugged outlines of the other rocks, this view has become a favorite one with the “eggers.”

Upon these islands, of three hundred and fifty acres, there is not a single tree or shrub to relieve the eye by contrast, or give change to the barrenness of the landscape. A few weeds and sprigs of wild mustard are the only signs of vegetable life to be seen upon them. To those who reside here it must be monotonous and dull; but to those who visit it, there is a variety of wild wonders that amply repays them for their trouble.

Some Italian fishermen having supplied our cook with excellent fish, let us hasten aboard and make sail for home.

Before saying “good-bye” to our kind entertainers, and again leaving them to the solitary loneliness of a “life near the sea,” we will congratulate them upon their useful employment, and ask them to remember the comforting joy they must give to the tempest tossed mariner, who sees, in the “light afar,” the welcome sentinel, ever standing near the gate of entrance to the long wished and hoped-for port, where, for a time, in enjoyment and rest, he can recover from the hardships and forgot the perils of the sea.

On our left, and but a few yards from shore, is an isle called Seal Rock, where the sea lions have possession, and are waving their lubberly bodies to and fro upon its very summit, and from whence the echoes of their low howling moans are heard across the sea, long after distance has hidden them from one sight.

After a pleasant run of five hours, without any sea-sickness, we are again walking the streets of San Francisco, abundantly satisfied that our trip was exceedingly pleasant and instructive.

Next: San Francisco • Contents • Previous: Mount Shasta

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/scenes_of_wonder_and_curiosity/farallone_islands.html