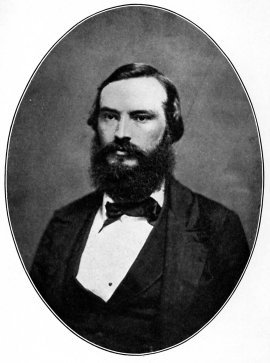

WILLIAM H. BREWER

1859

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > 1860-1861 Chapter 1 >

| Next: Chapter 2 • Contents • Previous: Introduction |

BOOK I

1860-1861

Panama—Acapulco—San Francisco.

New York.

Sunday Evening, October 21, 1860.

I shall sail at noon tomorrow, and drop a line before starting. I went to Chickering’s1 at Springfield, Vermont, Saturday night, October 13, after I left home and stayed until Monday noon. Monday night I spent in Boston, and went to Greenland Tuesday afternoon. I left there again for Boston early Wednesday morning. Wednesday night I went to Northampton, and Thursday, October 18, I came on here with Professor Whitney and his family, stopping a few hours at New Haven where I met old friends and had a short but pleasant visit. At Springfield I met the publisher of the valuable work on the trees of America, in five volumes, worth seventy dollars.2 He wants to learn more about the trees of California and offers to send me a copy of his work—quite a gift certainly. I also met Gray, the botanist, at Cambridge, and got much valuable information. He also gave me a useful book.

Whitney has been back to Boston and I have had to get the baggage on board ship including our apparatus, some $2,500 to $3,000 worth, belonging to him and to the Survey.

I took dinner with Mr. Brush3 today and tea at Hunter’s this evening. We sail on the North Star, the steamer Vanderbilt made his famous pleasure trip with. It has a full load of passengers. I have met quite a number of scientific men this evening who will see us off in the morning. I have had many letters to write and it is now past two o’clock.

My baggage from Washington has not arrived. If it is not here in the morning, I shall have it shipped by Freeman’s Express. It will be as cheap as to take it with me, but not so convenient.

At Sea.

October 26.

We sailed Monday noon, punctually as we expected. There was the usual crowd, and partings, and tears, and blessings—I was glad I had parted with my friends at home, not here in this crowd. It was a dark, nasty day, but it did not rain much. We passed out of the harbor, ran down the Jersey coast and before night we had left the land out of sight. We have since then kept due south. The weather has been growing steadily warmer. Today we crossed the Tropic of Cancer and we are now in the tropics in earnest. Our ship is a good one, but terribly crowded. I think there must be 1,000 or 1,200 on board—certainly the former number of passengers.

Caribbean Sea, off the south coast of Cuba.

Saturday, October 27.

Cuba has been in sight nearly all day, and it is now, at 5 P.M., vanishing from view beneath the sea. We now take our way across the Caribbean Sea and the next land we see will be the Isthmus. We have had a most lovely day with a fine breeze from the east, the trade wind, yet it has been intensely hot, like the hottest August day. We ran east of Cuba, about three miles from the shore. San Domingo (or Haiti) was in the dim distance, but Cuba was most beautiful. The east end of the island is very rough, high mountains rise from the interior, nearly as high as the White Mountains of New Hampshire.

WILLIAM H. BREWER 1859 |

Cuba is a most picturesque island. I regret that I could not see more of it. We are now nearly across the Caribbean Sea; will reach the Isthmus in the morning, when I must send this. This is a poor place to write because of the intense heat and the crowds on deck, which is now piled with trunks that have been brought out in the night to be weighed. Around is the clear deep blue Caribbean Sea. My baggage did not arrive at New York, so it will be sent by an express company.

Ship Golden Age.

Pacific Ocean, near Acapulco.

November 6.

We arrived at Aspinwall on Tuesday noon, a week ago today, and crossed to Panama the same day. The weather, although intensely hot, was cooler than usual. I wish I could adequately describe the gorgeousness of the vegetation of the Isthmus—it even exceeded the pictures imagination had painted—cocoanut trees, palms, bananas, plantains, oranges, lemons, limes, and other tropical fruits. Tall palms, mahogany, and such woods, vines hanging like ropes from the branches, parasitic plants growing over everything, made a scene I wish you all might see. We were detained more than half the night before we got on the ship at Panama, then found we could not sail all the next day, Wednesday; so I went ashore again and visited the town, for the ship lay a mile or two off, anchored. Panama is the most picturesque place I ever saw. It was once a place of much importance, walled about like the cities of the old world in the Middle Ages, but its glory has departed. Its walls are in ruins, and also many of its fine old churches are entirely in ruins, and over all is a most vigorous growth of tropical vegetation. Trees and shrubs flourish wherever they can get a foothold. This exuberance of vegetation is the feature that strikes me, reared in a colder clime. You have no idea of the dampness, especially at this, the rainy, season of the year. An old resident told me that clothing must be aired every day—even books on the shelves wiped every day, or they mold and rot.

The town seems quaint enough. Its tile roofs—no chimneys, for fires are only needed to cook by—its open houses—all make it a queer old place. There are a few Americans connected with the railroad. The better class are Spanish. The masses are black but speak Spanish. They are scantily clothed, the children entirely naked. All along the railroad we passed villages where the houses were only mere roofs upon poles or posts, no sides, the roofs steep and covered with palm leaves, the women with skirt only and the men with only pants, naked from the waist up, the children naked as cupids. The blacks have become the dominant race, and it occurred to me that perhaps in some of our warmer states we were following in the same way.

Wednesday at midnight we were off. We have had hot weather and a smooth sea ever since. Tonight we stop at Acapulco for coal, but it will be after dark and I do not know whether we can go ashore. We have a much more comfortable time on the Golden Age than we had on the other side. In eight days more we will be in San Francisco.

A word more about the Panama railroad. It is well built, its bridges of iron—indeed, iron is used wherever possible, for the wood rots in a year or so. The length is forty-eight and one-half miles, the fare twenty-five dollars, and freight accordingly; so you can well believe that it pays well. Most of the hands are blacks, but all the conductors are Americans. It does an immense business and is a great enterprise, but it cost four thousand lives to build it amid the swamps and miasma of that climate. It follows up the Chagres River about twenty-five miles, then crosses the ridges to the Pacific. The Bay of Panama is fine and large.

San Francisco, California.

Thursday Evening, November 15.

Tuesday, November 6, the day of the great election, was a quiet day on shipboard, and at about half-past eight or nine in the evening we ran into the harbor of Acapulco, in Mexico, where the ships coal. Much to the regret of us all we ran in by night and thus missed the beauties of that beautiful harbor. It is so completely locked in by hills that when in, one cannot see the ocean at all; it is completely secure from the storms of the ocean outside. In fact, it is the best harbor between Cape Horn and San Francisco.

The ship anchored in the bay, for there are no wharves; the coal and washing is taken on from lighters. Notwithstanding that it was night, a number of us went ashore. It is a picturesque place of about four thousand inhabitants, hemmed in by hills, and hot as Brazil. All the fruits of the tropics grow there, and I bought a basket of oranges, limes, plantains, and bananas; the last two fruits are very similar. The houses are all of the most open description—lattice doors and often lattice sides. The public square or plaza was filled with natives, some with fruits, shells, and liquors to sell to the passengers, others gambling with each other. I spent an hour looking at them gamble. They are nearly all Indians, but there is some negro and some Spanish blood, and Spanish is the language. Some of the girls were quite pretty.

The men who put the coal on the ship were in strong contrast with those we saw at Panama, in just so much as the Indian form is finer than the negro. The coal was in bags, on an old hulk moored in the bay, and was brought on board by these natives, and the effect of the light of the bright torches on these half-naked men in the gloomy night was picturesque beyond description. The coal is brought from the Atlantic states and costs the company from eighteen to twenty-five, and even at times thirty, dollars per ton in these Pacific ports. We coaled, took on cattle, etc., for provisions, and before morning had passed outside and were again on our way on the broad Pacific.

Wednesday, November 7, we kept nearly all day in sight of land, the high Cordilleras often in sight; in fact, they were always in sight when we could see the land at all, and some of the views of them were grand. I had never heard that the views of the mountains of Mexico and Central America were so fine from the ship, so I was entirely unprepared for them.

Thursday they were even finer, and Colima, the volcano, was in sight all day, although it was ninety miles inland and we not less than twenty miles off the coast. We saw it plainly when we were 150 to 180 miles distant, its massive cone-like peak rising against the clear blue sky. Sometimes it stood out clear, at other times clouds curled about its summit. The weather continued magnificent, indeed it has remained so ever since.

Friday, November 9, we crossed the mouth of the Gulf of California and had more wind and a rougher sea, although still comparatively smooth. The next two days we skirted along the coast of Lower California; its barren shores, parched and burned, looked desolate beyond description. On Sunday afternoon two passengers died, one a Mexican who got on at Acapulco, the other a child. Both were sick when they came on shipboard, and both died quite suddenly. They were buried that night, both at the same time. A hard rain squall happened just at that moment, making the scene doubly sad and impressive.

Monday and Tuesday we were along the coast of California proper; the shore often, but not always, in sight, and the weather much cooler. Thick coats were comfortable, and I could no longer sleep on deck. All along in the tropics I slept on the deck, wrapped in my blanket, with the sky overhead—it was not only delicious but glorious, considering the contrast between that and my stateroom, where four persons were crowded into a place scarce six feet square.

Wednesday morning (yesterday) we sailed into the Golden Gate, as the entrance to the harbor is called.4 It is a narrow strait between steep rocks, with a crooked channel. Inside, the broad bay spreads out, a calm placid lake, so large that all the ships of the world might ride there at anchor with room to spare, and yet so placid that it seemed like a mere pond. It is by far the most beautiful harbor I have ever seen, not even excepting New York.

As we had instruments to carry we did not hurry on shore, so it was nearly noon before we were fairly at our hotel, and our journey of nearly 6,000 miles brought to an end. It is over 2,000 from New York to Panama, and about 3,300 from Panama to San Francisco. And on the whole of this journey we had fine weather, indeed lovely weather; twenty days out of the twenty-three were as fine as our finest Indian summer.

This place I will not speak of now—it has astounded me. First, after our long trip by sea and by land we are still in the United States; second, a city only about ten years old, it seems at least half a century. Large streets, magnificent buildings of brick, and many even of granite, built in the most substantial manner, give a look of much greater age than the city has.

The weather is perfectly heavenly. They say this is a fair specimen of winter here, yet the weather is very like the very finest of our Indian summer, only not so smoky—warm, balmy, not hot, clear, bracing—in fact I have not words to describe the weather of these two days I have been here. In the yards are many flowers we see only in house cultivation: various kinds of geraniums growing of immense size, dew plant growing like a weed, acacia, fuchsia, etc., growing in the open air in the gardens.

Our arrival was anticipated by the Pony Express. All the papers had announced that the members of the Geological Survey were on their way, and yesterday and today all the city papers have noticed our arrival. Whitney and I get most of the puffs, some of which are quite complimentary.5 I have been introduced to many prominent citizens, tendered the use of libraries, etc. The Coast Survey offers many facilities, free passage on its vessels along the coast, etc. This afternoon Judge Field and the Governor of the State leave Sacramento to come down here to see us; we shall see them tomorrow.

We found the news of Lincoln’s election when we landed, an unprecedented quick trip of news. I have been out to see fire-works, processions, etc., in the early part of the evening, so now it is late. Good night.

NOTES

1. J. W. Chickering taught at Ovid Academy with Brewer, 1857-58.

2. F. Andrew Michaux and Thomas Nuttall, The North American Sylva (Philadelphia, 1857).

3. George Jarvis Brush, a classmate of Brewer at Yale (Ph. B. 1852); was Professor of Metallurgy at Yale, 1855-71; Professor of Mineralogy, 1864-98; emeritus, 1898 until his death in 1912.

4. This name was given by Frémont before the discovery of gold. In his Geographical Memoir upon Upper California, in Illustration of His Map of Oregon and California, 1848, he says: “Called Chrysopylae (Golden gate) on the map, on the same principle that the harbor of Byzantium (Constantinople afterwards) was called Chrysoceras (Golden horn). The form of the harbor and its advantages for commerce (and that before it became an entrepot of eastern commerce), suggested the name to the Greek founders of Byzantium. The form of the entrance into the bay of San Francisco, and its advantages for commerce (Asiatic inclusive), suggest the name which is given to this entrance” (p. 32).

5. An editorial in the Daily Alta California speaks of Brewer as “a gentleman of splendid scientific attainments.”

| Next: Chapter 2 • Contents • Previous: Introduction |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/1-1.html