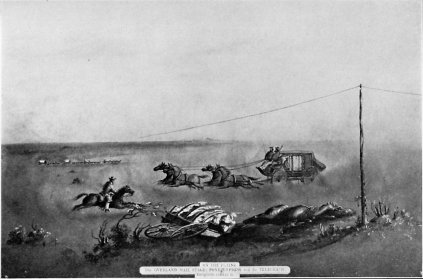

RAPID TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATION IN THE EARLY SIXTIES

From a drawing by Edward Vischer

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > 1861 Chapter 6 >

| Next: Book 3 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 5 |

Overland Telegraph—Benicia—Judge Hastings—Suscol—Napa—Yount’s—St. Helena—McDonald’s—Pluton River—Pioneer Mine—The Geysers—Rain—San Francisco and Winter Quarters.

Camp 62, near Benicia.

Saturday Evening, October 26, 1861.

On Tuesday last we came on from San Ramon, intending to come a few miles and stop over one day, but finding no place to camp we came on to Martinez.

On Wednesday night Professor Whitney came and brought with him a tremendous package of letters for us all. Peter got the sad news of the death of his mother, who lived in Illinois (or Iowa). He had not seen her for two or three years, but often spoke of her in terms of the tenderest affection. He is much depressed by it.

I had expected that Professor Whitney would remain with us, but Pumpelly has accepted a place on the Japan affair, so the Professor has to go up with Ashburner. He spent but one day with us.

That day, Thursday, October 24, was a most memorable one for California. The last piece of wire was put up on the Overland Telegraph, and dispatches were received from the East, Salt Lake, etc. You cannot appreciate the importance of this, but great as it is, it made but little excitement here. A dispatch leaving New York at noon may now be received in San Francisco at a quarter before nine of that morning, or over three hours ahead of time!

This line is built by two companies acting in concert and meeting at Great Salt Lake City—the Overland Telegraph Co., owned in San Francisco, on this side, and the Pacific Telegraph Co., owned in the western states mostly. The latter has put up 1,600 miles in four months! News may now come by telegraph from Cape Race, seventy-two degrees of longitude east, 3,500 miles distant in a direct line, or 4,500 miles by the telegraphic route—surely a most gigantic circuit—the difference in time being nearly five hours. The tariff to New York City is now a dollar per word, and for the first two days the office has been crowded with dispatches.

Friday morning we crossed the ferry to Benicia and camped four miles north of the town. As an item of California prices, we paid nine dollars to be ferried over from Martinez on the regular (steam) ferry, and had our whole party been there it would have been ten dollars. Hoffmann and Professor Whitney were absent. The former we had sent to San Francisco. He returned that evening (last night) and brought papers with news from New York up to the previous evening.

This morning a cold heavy fog hung over everything, and many shrugged rheumatic shoulders. Tonight I shall take to the tent and sleep there after this.

Camp 63, at Suscol, five miles from Napa.

November 1.

Saturday night, October 26, was foggy, but it cleared up in the morning and the day was most wonderfully clear. It was the loveliest day for a long time. Two gentlemen called at camp—Judge Hastings and a Mr. Whitman. Judge Hastings invited us to dinner on Sunday. After dressing, Averill and I went into town and attended the Episcopal church, the first service of that denomination I have attended for a long time. The church was small but neat, the attendance good, and very “respectable.” At the close, we were met at the door by Mr. Whitman, one of the vestrymen, who invited us to his house near to take a whiskey cocktail. As it was too early to go to Judge Hastings we went in, he being an old friend of Averill’s. We sat an hour, walked into his garden, the most noticeable feature of which was an abundance of most delicious almonds, now just ripe. The cocktail story may seem a large one, but it is literally true—you have no idea how prevalent drinking is in this state—one scarcely ever goes into a house without being invited to drink. If you go to dinner you are asked to drink before, but a refusal to drink is always courteously received—at least, I have always found it so, as I quite seldom accept the invitation except wine.

At three we went to Judge Hastings’ and were most cordially received. The Judge is quite a noted man here, has made much money, is a man of influence, was once one of the supreme judges of the state.1 He has a pretty wife and several children; some of the latter very pretty, others not.

Don’t ask me to describe dinners, that is out of my line. The dinner was quite ordinary—two or three courses. The waiters were three Digger Indians, of the homeliest kind, two young squaws, and a boy—far from neat, yet tolerably handy. After dinner Mrs. Hastings bragged of her Indians, told me all their merits and demerits, admired them as servants, but not as cooks—she has a Chinaman cook. So are the races mixed up here. Judge Hastings is a convert to the Roman church; his wife is a leading Presbyterian here. He, like all proselytes, is very zealous, is probably the most influential man in that church here. He had traveled abroad, and gave us a most interesting description of his presentation to the Pope.

Benicia is noted for its schools. There is a college, and there are two large female schools. One of the latter is Roman Catholic, in charge of nuns (sisters, rather) of the order of Ste. Catherine. They have recently made great enlargements, put up a new building at an expense of thirty or thirty-five thousand dollars, and have made proportionate improvements. Judge Hastings asked if we would like to visit it, so we did, were introduced to the “Mother” (Mother Mary) at the head, and went through many of the rooms. About thirty-five sisters have charge, dressed in the most untasteful white garbs of their order. They are very kind and the pupils are greatly attached to them. There were about a hundred girls (besides the day scholars), who, of course, are kept very secluded. It being Sunday there were no studies, but we met them all coming out of the chapel and saw most of them there or in some large recreation rooms. A peculiar feature was an examination hall, apart from the other buildings, in the grounds. It is a building with roof, lattice sides, and floor, built in a hollow, with the ground rising on each side forming a natural amphitheater. It was an excellent arrangement, but of course only suited to a Californian climate.

Our visit there so prolonged our stay that we rode back after dark in the chilly night air. The night was glorious, but cool. The day had been of the most lovely kind, the sky intensely blue, and the mountains across the bay, twenty miles distant, seemed scarcely three miles away.

Monday, October 28, was another magnificent day, clear as the previous one, harbinger of the fall rains they say. Myriads of wild geese flew over our camp, as they have for several days, their numbers incredible. At this season of the year they come from the north to winter in this state. They congregate on the plains, and at times hundreds of acres will be literally covered with them. I believe I wrote last winter of the immense numbers we saw near Los Angeles.

We raised our camp and moved up the Napa Valley to Suscol Ferry, five miles from Napa. The roads were dusty almost beyond endurance. There is much travel, and every team moved in such a cloud that it was impossible to see it at any distance—you only saw its cloud of dust.

We camped by a pretty brook, near the Suscol House. On our way we passed the pretty little village of Vallejo (pronounced here in the Spanish style Val-lay´-ho), where the United States has a navy yard. We passed through a fertile

RAPID TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATION IN THE EARLY SIXTIES From a drawing by Edward Vischer |

After camping, Peter shot a fine wild goose near camp. A flock came down in a stubble field, and he stole up and killed one.

Camp 64, Sebastopol.

Sunday, November 3.

Tuesday, October 29, was a cloudy morn, but soon partially cleared up. Hoffmann and I started for a sharp rocky peak some six or seven miles east, and, as the fields were fenced, we took it afoot—a long walk. We reached it, a sharp rocky knob 1,332 feet high, from which we got bearings of all the surrounding country. A cold wind swept over the summit, but although the sky was cloudy, the air was clear, and the prospect extensive. The arms of the bay, with the winding bayous (called here “sloughs”) in the swamps around them, were very beautiful, the effect heightened by the rugged mountains on the north and northwest.

As the wind was so high and raw, we crept behind some bushes on the lee of the hill and hung up the barometer behind them and waited there half an hour for observations, taking a quiet smoke and enjoying the lovely prospect beneath. The wind shrieked over our heads. The pipes smoked out, observations taken, barometer put up, as we emerged from the bushes we saw a dense mass of clouds sweeping down from the north with rain. The whole aspect of the sky in that quarter had changed while we were in the bushes. We struck for the camp “double quick” pace, but had not made over one or two miles when the clouds came sweeping over us. Our way here lay along the crests of a series of ridges for about three or four miles—the ridges in places quite sharp, in other places branching off in spurs—easy enough to see in the clear air, but blind enough in the dense gloom of the thick fog that shrouded us.

With this cloud and fog came a fine rain, sweeping with the wind. But a few minutes were necessary to wet us to the skin, cold and uncomfortable, but the smell of the rain, the damp air, the smell of wet ground, was delightfully refreshing. It carried me back to days of summer showers, to green grass, fresh air, and no dust—this feature was positively delightful, in spite of the discomfort of the wet.

We pushed on our blind way, facing the stiff wind, and as we neared the end of the ridge where we were to descend into the valley the rain ceased. In a few hundred feet we got below the clouds, and the lovely Napa Valley, with its neat village, pretty farms, green trees, and pretty sites, lay below us, lit by patches of sunshine here and there. A spot of sun lay directly on the village of Napa, six or seven miles distant, producing a delightfully beautiful effect.

We found it had rained but little at camp, not enough to lay the dust. The rest of the afternoon was quite fair, but not clear, and dense masses of clouds hung over the ridges we had left. We changed our clothes for dry ones. Mike soon had the goose roasting, and at half-past four it was served up in good style and partaken of with an appetite any epicure would envy. The skeleton was dismembered, the bones polished, and every vestige that was eatable soon disposed of.

The evenings are getting longer. The weather drove us all to the tent to sleep, and after all the preparations for rain were made, the long evening was whiled away with reading and euchre, varied by a game of “seven-up.” But we had no more rain.

Wednesday there was no rain, but a dense fog hung over everything. Averill went to Napa for letters. I lounged down to the tavern to read the news. While there, a rough but intelligent-looking man entered into conversation and invited me to his house a few rods distant for a “glass of good cider.” I went, got the cider, the best I have tasted in the state, and went into his house. I found him an intelligent man, quite a botanist, and even found that he had some rare and expensive illustrated botanical works, such as Silva Americana, worth sixty to eighty dollars—the last place in the world I would have looked for such works. He does not own the ranch, is merely a hired man, having charge! There is an orchard of ten or twelve thousand trees and a vineyard—he makes wine and cider and sells fruit.

It cleared up, and Averill and I took a tramp of ten or twelve miles over the hills—visited a knob over 1,700 feet high and got a magnificent view. The day was most delightful and clear after eleven o’clock.

Thursday, October 31, another foggy morning. Mr. Beardsley came to camp and invited us to his house for more cider. We went, spent an hour, when it cleared up, and we started for a peak seven or eight miles northeast. We got on the wrong ridge, got up about two thousand feet, saw much of geological interest, and got back long after dark.

The hills of the ridge to the east are of strata derived mostly from volcanic products—lava, pumice stone, volcanic ashes—which appear to have been thrown up in water and deposited in strata many hundred feet thick. After being thus deposited, the strata have been upturned, much twisted and broken, and again baked by volcanic agencies—a most complicated affair. These rocks are of all colors, red as brick, gray, black, brown.

Friday, November 1, I sent Averill and Hoffmann to a point we failed to reach the day before, while I visited some points nearer camp, collected and packed specimens, observed barometer. The day was very clear, after a cloudy morning, and they had an all-day’s ride of it, getting back after dark. They reached the point, 2,200 feet high, and got good bearings and had a most extensive view, reaching to San Francisco and Stockton on the southwest and southeast and far into the mountains in the opposite direction.

The swamps bordering all the rivers, bays, or lakes, are covered with a tall rush, ten or twelve feet high, called “tule” (tú-lee), which dries up where it joins arable land. On the plain below camp, fire was in the tules and in the stubble grounds at several places every night, and in the night air the sight was most grand—great sheets of flame, extending over acres, now a broad lurid sheet, then a line of fire sweeping across stubble fields. The glare of the fire, reflected from the pillar of smoke which rose from each spot—a pillar of fire it seemed—was magnificent. Every evening we would go out and sit on a fence on the ridge and watch this beautiful sight, some nights finer than others.

Saturday morning we started, first to Napa, five miles, then on to this place, nine or ten farther. We had gone but a short distance when we came on a large flock of geese, several hundred feeding in a stubble field close by the road. They are very sagacious, always keeping several on watch while feeding, and never allowing a man to approach on foot. But they are not so afraid of horses and wagons going along the road. We stopped and loaded our double-barrel shotgun. Peter walked behind a mule to within eighty yards, then shot. The geese rose, but three fell; two we got, the other fell in the tule where we could not get him.

The various tricks that hunters resort to, to kill these geese, are ingenious, and the sagacity of the geese is as marked. The hunters lie in the bushes and shoot the geese as they fly over, but the geese learn in a few days to fly high over these bushes. Sometimes they train a horse, but the geese soon learn to avoid a horseman. On the San Joaquin plain, where there are multitudes of cattle, which can approach the geese, an ox is trained so that a man can walk behind into the very flock and bang away with both barrels and kill several, but the geese soon learn which ox is the suspicious one. The geese bring a good price in market. (N.B.—Mike is now roasting a goose outside the tent—I smell the savor thereof—I wish you could dine with us.)

To go on—Napa is a pretty, American town, on a stream large enough for a small steamer to ply to San Francisco, and is a place of much trade. We stopped a few minutes. I got letters, one from Professor Whitney, one from home—which I read after mounting, as I rode along.

We came on nine miles farther up the valley. Pretty farms, neat farmhouses, fine young orchards, lined the way. The bottom is three to five miles wide most of the way, very fertile land, and the fields have scattered over them many most grand oaks, which would be an ornament to any park with their broad spreading branches, drooping at the ends like those of an elm—majestic trees.

But the feature of that nine miles was the dust, dust! DUST! The road has been much used, hauling grain, and from fence to fence the dust is from two to six inches deep, fine as the liveliest plaster of Paris, impalpable clay, into which the mules sink to the fetlock, raising a cloud out of which you often cannot see. Each team we met was enveloped in a cloud, so that often you could not see whether it was a one-, two-, four-, or eight-horse team we were meeting; the people, male and female, were covered with dust—fences, trees, ground, everything covered. Need I say that on our arrival to camp a wash was one of the first performances?

San Francisco.

November 17.

Safety back here again in the city. The last two weeks have been such laborious ones—one week in the rain—that I have done no letter writing. I will now bring up my journal as I have time.

This was left off at Camp 64, at Sebastopol, the “Yount’s” of your maps.2 And so it should now be called, in justice to the settler, Yount, who settled there twenty-eight years ago.3 His story seems a romance. He was a western man who wandered across the Rocky Mountains, lived with the Indians, hunted, and trapped. While plying the trade of trapper he entered San Francisco Bay, pushed up its northern arm, entered Napa Valley, and found this lovely spot, inhabited by savage Indians and a few semi-savage Mexicans.

In his youth, in a western state, a fortune teller had predicted to him his future home, settled in a lovely valley, etc. Here seemed to be the place—a fertile valley, enclosed by high mountain ridges, a rich bottom with grand trees, a stream rich in fish. He did not stay, however, but the prediction of the sibyl so often came up to him that he returned a year or so later and got a grant of the Mexican Government of two leagues of land in the valley. He built him a cabin—at once fort, fortress, and home.

By his force of character and kindness he overcame the Indians and made them such warm friends that to this day many live on his ranch. With his rifle he compelled the submission of the treacherous Mexicans. His exploits and adventures smack of the marvelous, but he held his place, fully determined that Fate had destined that spot to be his home. He raised cattle, had a village of Indians on his ranch, and lived that patriarchal life for fifteen years before the discovery of gold here and the immigration. His Mexican grant was confirmed by the United States Government after much delay and difficulty, and now he is surrounded by thriving and valuable farms, fine orchards, above and below him. We camped on his land, but missed seeing him. Here are the “heads” for a “romance” or “tale” for some future author.

One evening while at this camp I attempted to go up to Yount’s and call on the old man as he had sent us an invitation. It was but a mile or so from camp. We had had a hard climb that day and the others declined going, so I started alone. I passed the Indian village on the ranch. It was after dark. The homes were mere sheds covered with bushes or rushes, the front side entirely open to the air. These seemed their “sitting rooms.” A bright fire lit up the hut. Standing, lying, squatting around the fires were the Indians—some with bright red blankets around them—squaws doing various work, dressed in skirt and chemise, the latter quite scanty in the neck, and in many of the middle-aged women showing enormous and flabby breasts—children playing about. The whole, lit up by their bright fires, made a most picturesque and peculiar picture. The Indians of this state, except some of the tribes in the extreme north, are perhaps the ugliest looking in North America—they are certainly much inferior to the other tribes I have seen. I missed the way, for the night was very dark, and I could not find Yount’s house, so I returned to camp. I thus missed seeing him, as I had no other opportunity.

November 4 we climbed a high rock ridge east of the valley—a rough craggy mountain 2,147 feet high, its sides furrowed by canyons, and very picturesque as seen from the valley. Although not very high it was quite a rugged climb and the view from the top decidedly fine. We had no lunch along, but a roasted goose about sunset answered for dinner and supper both, and some prophesied for breakfast too. But the prediction proved untrue—we ate it all, polished the bones, and left not even a “wreck” of its trimmings, and morning found us hungry again, of course. By the way, we came near losing our geese. The night after our arrival, just after dark, a stranger approached camp. We did not see him, but his presence was unmistakable. Mike, notoriously careless, had tied the geese in a bush, quite too near the ground. We “heard something drop,” rushed out, cautious, for we had a very formidable thief to contend with, but by our infernal yells, shouts, pounding on a board, etc., he left the geese and sneaked away through the bushes. We then tied them so high that no marauding skunk could get them, but he hung around during the night, loading the air with the odor of his presence.

November 5 Hoffmann and I climbed a ridge west of camp, about five or six miles distant. A steep sharp ridge rises from the valley, very steep, its top a very sharp point, 2,400 feet high, with no rocks in sight and but few trees. Its steep sides and sharp top show a smooth surface of dark green chaparral —beautiful to the lover of scenery, but forbidding to our experienced eyes. We have seen too much of that treacherous surface, which looks so inviting in the distance but is so difficult and laborious to penetrate.

A ride of about four miles up and across the valley, then back through the fields, and then we strike up a ridge. A few hundred feet are gained, when suddenly a board fence bars further progress. But we are ready for the difficulty, as it is one we often meet. I have some nails in my saddlebags, my geological hammer is the right tool—I soon knock off the top boards, jump our mules over, replace the boards with fresh nails, and ride on. We soon get into a cattle trail that carries us up until it gets too steep to ride farther. We tie and make the rest on foot, find the chaparral not tall, and less difficult than was anticipated.

The view from the top is finer than any we have had since crossing the bay, more extensive and more grand. San Pablo Bay gleams in the distance; the lovely Napa Valley lies beneath us, with its pretty farms, its majestic trees, its vineyards and orchards and farmhouses. Its villages, of which three or four were in sight, the most picturesque of which is St. Helena, are nestled among the trees at the head of the valley. Bold rocky ridges stand across the valley, a bold broken country around us. To the northwest lies the distant valley of the Russian River, one of the finest in the state, many thinking it even finer than the Napa and the Santa Clara valleys. But the feature is Mount St. Helena, rising to the north of us, over four thousand feet—steep, bold, and rocky—an object of sublimity as well as beauty.

We stayed for nearly two hours on the peak. We were tired and hungry. I thought we had no lunch. Hoffmann had told Mike, however, to put up something. We searched my saddlebags, and lo! six quails, finely broiled (cold), with bread, salt, etc! How we feasted! and the scene looked even more beautiful after it. As the peak was without a name we called it Mount Henry, as it was something like Mount Bache across the bay, and we thought it well to honor the distinguished man of science.4

Our return was without especial interest. Found a goose roasted for dinner, the last of the season for us—last but not least. It went the way of its predecessors.

Professor Whitney came to camp the evening of the fifth. It had been our intention to visit the new quicksilver region of Napa County and the Geysers, but we had already exceeded the time set for withdrawing from the field. The rain had kept off unusually long, and it was feared that when it would once begin there would be no stop. The Professor was more than half inclined to turn back as it began to look like rain, but I was anxious to get up into that country, even if it were only for a week, and I carried my point.

The next day we started on, following up the valley eighteen miles. The bottom grew narrower, the hills on each side more rugged, and trees more abundant. The pretty little village of St. Helena, with its fifty or more houses, many of them neat and white, nestled among grand old oaks, was very picturesque. We got meat and vegetables and pushed on eight miles farther and stopped at Fowler’s Ranch, Carne Humana (“Human Flesh Ranch”) but we could not find out the origin of the name—near some quite noted hot springs. These last are curious—a number break out around the base of a low but sharp conical hill that rises in the valley. The springs vary in temperature from 157° to 170° F. The waters smell quite strongly of sulphur and have some considerable reputation in the cure of diseases. There is a fine public house with bathhouses, etc.5

The weather continued to look like rain, but November 7 we pushed on. The trees grew more numerous, not only oaks, but fir or spruce, pines, the majestic redwood here and there with trunks towering perhaps two hundred feet high, and a lovely madroña tree growing finer than we had seen it before. This is a beautiful tree, has leaves like the magnolia, rich dark green, sheds its outer bark every year, and is very peculiar as well as beautiful.

Here let me state that your maps will give but little satisfaction for the region I am to describe. All north of the Napa Valley is guess work—much totally wrong—only a few of the main features are correct. There is a Mount St. Helena (not St. Helens), but no Mount Putas (Whore Mountain). The latter is probably the one now called Mount Cobb, as there is a high Mount Cobb near where the map puts Mount Putas. But all the region through to Clear Lake and on to the Humboldt is a very rough country, of which there are as yet no maps anywhere near correct. We, of course, are getting as many details and bearings as we can, and will eventually, I hope, get a tolerably good map. But do not wonder if my letters and the maps disagree during the remainder of this trip.6

We passed up to the head of the Napa Valley, then over a low divide toward the northwest and descended into Knight’s Valley, a lovely valley watered by a tributary of the Russian River. The divide between these valleys on the south side of Mount St. Helena is very low, not over five or six hundred feet high. We passed down Knight’s Valley a few miles, then across by an obscure road, over low hills to McDonald’s, on a creek of his name, a tributary of Knight’s Creek. Here we camped—Camp 66.

McDonald is a quiet, fine man, and what is rare in such regions, a pious man. He settled here twelve or fifteen years ago, then the remotest settler in this region between San Francisco and the settlements in Oregon. His wife, then but twenty years old, is still pretty, an intelligent and amiable woman. It must have requiredcourage to settle here at that time, surrounded by Indians, so far away from civilization.

As this was the “headwaters” of wagon navigation we made our preparations to go on with mules. To the north of this lies a region now creating much excitement from the discovery of many quicksilver “leads.” This we wished to hastily visit.

We had a cold night, and November 8 the temperature was 37° F. in the morning—but the sky was intensely clear. We started, Professor Whitney, Averill, and I, each with a mule, and Old Jim carrying our blankets and some provisions packed on his saddle. The Professor and I carried saddlebags on our mules, while tin cups, pistols, knives, and hammers swung from our belts. We agreed to ride the two mules by turns, but it proved in the end that it was little riding that any of us did. Mr. McDonald went with us on foot as guide the first day. First we went up the valley of the little stream two or three miles, then struck up the ridge and crossed Pine Mountain, some 3,000 or 3,200 feet high, commanding a glorious prospect from its summit. The ascent was steep, the trail very obscure, and we would never have found it alone, even with all our mountain experience.

The summit of the ridge has some scattered pines, but on descending its northern slope we passed through a forest—firs, pines of several species, oaks, madroñas, etc., and with these the strange “nutmeg tree”—a curious tree something like a pine, more like a hemlock, but bearing fruit in size, shape, and taste very like a nutmeg.7

We descended a few hundred feet into a canyon, where a cabin had been built beside a fine brook. It was now deserted, but here we camped, unloaded, and picketed our mules to feed, then descended into another wild canyon to a claim that was being worked.

On our return we found two other men had followed us, with pack-horses, having “interests” in some of the leads. A fire was built in the cabin, a dirty coffeepot found, which we cleaned up, coffee made, bacon roasted, and we had a comfortable supper, after which we sat by the bright fire and listened to the tales of pioneer life and adventure in these wilds. The rest slept in the cabin, but the Professor and I spread our blankets out under a majestic fir tree. The night was clear, the stars very bright, twinkling through the floiage; the sighing of the wind through the pines carried me back to recollections of other years and far distant scenes. The night was cold, but we were tired and slept well. To be sure, we were not over ten miles in a direct line from camp, probably not that, but distance in such places is not to be reckoned by miles but by the hours required to accomplish them.

November 9, by early dawn, we were astir and before the sun had gilded the mountain tops had breakfasted and packed up. We had but four miles to make that day, in direct line, but such miles! On our way we visited several leads, some quite rich. But such a trail—across steep ridges, zigzag, up and down, through deep gulches, over ridges—one of which was three thousand feet high and two thousand feet above other parts of our trail—through chaparral. In one place we were two hours making one mile in a direct line. We struck a trail, however, and descended into the valley of the Pluton River near its head—a canyon rather than valley—where the furnace of the Pioneer Mine is situated.

Here are the furnace, smith shop, and the homes of the workmen, among the trees, in a most picturesque spot, and, although in a canyon, still over two thousand feet above the sea. No wagon road leads here—everything must be packed on mules, even the fire brick for the furnace, tools, even an anvil; a wagon had been taken apart and packed in over a trail that crosses ridges over three thousand feet high.

We were most cordially and hospitably greeted and welcomed by Mr. Wattles, the foreman of the mines. We spent the rest of the afternoon in examining the furnaces and in visiting the “Little Geysers,” some remarkable hot springs near. The furnace was new and but two charges had yet been burnt in it. Great hopes are entertained of its eventual success. The ore of the Pioneer Mine is remarkable for its being native quicksilver, or the metallic quicksilver mixed with the rock. In places the rock is completely saturated with the fluid metal. It appears in minute drops through the whole mass—shake a lump and a silver shower of the glittering metal falls from it. It sparkles in every crevice, and sparkles like gems on the ragged surfaces of the freshly broken rock. Sometimes a “pocket” will be broken into of quartz crystal, pure white quartz filled entirely or in part with the metal. Break into such a pocket and the mercury pours out, often to the amount of several ounces, and even pounds—over six pounds of the pure metal has been saved from a single such pocket.

The mines are on a hill at an altitude of near three thousand feet, or eight or nine hundred feet above the furnaces. The ores are packed down on the backs of mules. How profitable the mines will prove remains to be seen by experience. The principal mines of this region are within an extent of about six or seven miles, and on the line of the leads many are prospecting, digging tunnels, etc., the majority of which must bring only disappointment and loss. Yet some will, in all probability, make money. More mines of the same metal have been found a few miles distant, which we did not visit.

We commenced the season’s work a year ago, intending to work up the Coast Range to the Geysers, then to go into winter quarters. Here we were, within less than four miles (six or seven by the trail) of the spot, late in the season. Although it was Sunday and looked like rain, this four miles must be made and the season’s work finished. The next day we might not do it, if the rains set in, as they bid fair to; so, Sunday, November 10, we started on our way. Mr. Wattles and another man from the mines accompanied us.

First we went up a very steep slope through a forest, then through chaparral to the summit of the ridge. We rode along the crest several miles, commanding one of the most sublime views for wild scenery since leaving the southern country. We rose to the altitude of about 3,500 feet. Around on all sides was a wild and rough country. We were higher than the country south, but on the north mountains rose higher than we were. The air was very clear, although the day was cloudy, the sun appearing only at times.

To the west of us rose Sulphur Mountain, a sharp conical peak 3,500 to 3,700 feet high, sharp, regular, and covered with dark green chaparral, like a great green mat. At times clouds curled over its summit, at others they rolled away and the sharp cone stood out against the cloudy sky. To the southwest lay the beautiful valley of the Russian River, some villages scattered in it, mere specks in the distance; beyond it were the rough ridges between it and the sea, against which heavy masses of cold fog rolled in from the Pacific.

To the south we could see the broken country lying between the Napa and the Russian River valleys, the Santa Rosa Valley, the black peak of Tamalpais by Tomales Bay, and the Bay of San Francisco. To the southeast was Napa Valley with rugged ridges east of it; and at the head of the valley stood the grand St. Helena, towering over a thousand feet above us, its rugged sides scarred by the elements, sometimes clear and distinct, at others with heavy manes of clouds drifting across its rocky brow for two thousand feet down its sides.

To the north was the deep, almost inaccessible canyon of Pluton (Pluto’s) River, more than a thousand feet beneath us, and towering beyond it stood Mount Cobb, which, though not a thousand feet higher than our position, was enveloped in masses of cloud at times, although occasionally its tall pines stood out marvelously clear. Then we could see the valley of Clear Lake and the rugged mountains around it.

The scene was not merely beautiful, it was truly sublime. But we returned from the ridge, down the steep sides of Pluto’s Canyon, and soon lost all this extensive view. The hill was so steep that we walked, leading our mules. On descending the slope, we saw the pillar of steam rising, several miles distant, and when more than a mile, we could see the Geyser Canyon very distinctly and hear the roaring, rushing, hissing steam. We were soon on the spot. The principal springs or geysers are in a little side canyon that opens into Pluton Canyon.

Here let me say, by way of introduction, that the geysers are not geysers at all, in the sense in which that word is used in Iceland—they are merely hot springs. Their appearance has been greatly exaggerated, hence many visitors come away disappointed. They were first seen by white men some nine or ten years ago, and such very extraordinary descriptions were given, that it was supposed that the whole world would flock to see the curiosity. All the facts were magnified, and fancy supplied the entire features of some of their wonders. But a company preëmpted a claim of 160 acres, embracing the principal springs and the surrounding grounds, built quite a fine hotel on a most picturesque spot, and at an enormous expense made a wagon road to them, leading over mountains over three thousand feet high. But the road was such a hard one, the charges at the hotel so extortionate, and the stories of the wonderful geysers so much magnified, that in this land of “sights” they fell into bad repute and the whole affair proved a great pecuniary loss. The hotel is kept up during the summer, but the wagon road is no longer practicable for wagons and is merely used as a trail for riding on horseback or on mules.

The springs cover an extent of a number of acres, but the principal ones are in a very narrow canyon with very steep sides. They break out on the bottom and along the sides up to the height of 150 or 200 feet, and on a little flat nearby. There are hundreds of springs—of boiling water—boiling, hissing, roaring. The whole ground is scorched and seared, strewn with slag and cinders, or with sulphur and various salts that have either come up in the steam or have been crystallized from the waters.

Passing over the flat we saw several of these—many in fact—here a boiling spring, there a hole in the ground from which steam issues, sometimes as quietly as from the spout of a teakettle simmering over the fire, but at others rushing out as if it came from the escape pipe of some huge engine. The ground is so hot as to be painful to the feet through thick boots, and so abounds in sulphuric acid and acid salts as to quickly destroy thin leather—it even chars and blackens the fragments of wood that get into it.

Near some of the springs a treacherous crust covers a soft, sticky, viscous, scalding mud; one may easily break in, and several accidents more or less serious have thus occurred. Quite recently a miner was so badly scalded as to be crippled, probably for life. Sulphur often issues with the steam and condenses in the most beautiful crystallizations on the cooler surface. Specimens of sulphur frostwork are of the most exquisite beauty, but too frail to be removed. We crossed this table and descended into the canyon above the geysers and followed it down. I found some flowers out in the canyon above, in the warm steamy air, of a species that elsewhere is entirely out of flower.

One can descend into the canyon and follow it down with safety, a feat that seems utterly impossible before the trial. Here is the grand part of the spectacle. Here are the most copious streams, the largest and loudest steam-jets, the most energetic forces, and the most terrific looking places. Standing part way down the bank at the upper end of the active part, where the canyon curves so that all its most active parts are seen at a glance, the scene is truly impressive. It seems an enormous, seething, steaming cauldron. Steam or hot water issuing from hundreds of vents, the white and ashy appearance of the banks, the smell of sulphur and hot steam in our faces, combined to produce an entirely novel effect.

We descended and followed down the canyon, threading our way on the secure spots. Hot water or steam issued on all sides—under us, by our side, over us, around us. Sometimes the whole party was enveloped in a cloud of vapor so that we could not see each other, at other times this was blown away by the winds. Once the sun came out from between the clouds and shone through this steamy air down on us, lurid, yet indistinct. In one place a rocky pool of black rock several feet in diameter, filled with thick, black water—black from sulphuret of iron, black as ink—was in the most violent agitation. It is the most peculiar feature of all the geysers and is well called the Witches’ Cauldron. The water, black and mysterious, boils so violently that it spouts up two or three feet from the surface, inclosed in this rocky wall.

A considerable stream of hot water issues from this canyon, and a short distance below are sulphur banks where hundreds, or even thousands, of tons of sulphur could be cheaply obtained. A curious fact is that a low order of plant, like confervae or “frog spawn” grows in this hot water, most copiously in water of 150° F., and even on the margins of springs of a temperature of 200° F., and over surfaces exposed to the hot steam. As the springs are at an altitude of 1,600 or 1,700 feet, the water boils at a temperature of about 200° F., so these plants literally grow in boiling water! I have obtained specimens, but owing to their character, they were very unsatisfactorily preserved.

We returned to the house, where our friends had ordered dinner, but they were very tardy in getting it. We had been a long time without news, and a man brought a recent slip, an “extra” of telegraphic news, from Petaluma, telling of the bombardment and taking of Charleston (which has since proved untrue), which called forth three hearty cheers. After a tedious wait dinner was announced, and after we had eaten we went out to saddle our mules.

Suddenly the sky had become darker and more threatening. We were soon off, but on reaching the ridge summit we were enveloped in a thick, driving, drizzly fog that rolled in from the sea, soon wetting us to the skin, and making our teeth chatter. The wind, cold and raw, swept over the ridge with terrific violence—in places it almost stopped our mules—there was no rain, but much wet. Yet we rode along light-hearted, for we had reached the goal of our summer’s hope, we were on the back trail, the rain had deferred its coming a month later than usual—for us.

Dripping with wet we plodded our way through the thick clouds and fog. Luckily our guides were well acquainted with the trail, for in a fog one is easily lost in these wilds and it would be terrible to be caught out on such a night. But we got back safely, and had scarcely got secure in the cabin when the rain fell in torrents. We got supper, then built a big fire and dried as well as we could before it. But how it rained! It came through the roof in many places, but we were tolerably secure. We listened to stories of the mountains, got partly dry, picked out the driest places to spread our blankets, and were soon asleep.

I awakened several times, each time to hear the wind howling through the pines, the rain pattering on the thin roof and sides of our cabin, and dripping on the floor. But it stopped before dawn, and the morn was tolerably fair. We packed our saddlebags with specimens, and two boxes besides, which were packed on my mule, so all the mules were loaded. We mounted the hill for our return, visited the Pioneer Mine, were shown the trail to take over the mountains, bade adieu to our kind but rough host, and started on our way.

The feature of our return was the grand view we had of the rocky peak of St. Helena. We found the best view from a ridge over 2,000 feet high, where we could take in the whole mountain from base to top at a glance—its 4,500 feet of crags and rocks furrowed in canyons.

We got back before night and made our preparations for departure. The rainy season had set in, we must hurry back to San Francisco. In our absence Hoffmann had attempted the ascent of Mount St. Helena. He got within 400 feet of the top, and reckoned it about 4,500 feet high or a little less.8

Our preparations for departure were premature, for it began to rain in the night very hard, and it rained nearly all the next day. We counseled about going on in the rain, for it might not stop for a week, but decided to wait one day for it to stop—longer we could not for want of provisions for men and mules. But in the afternoon the rain ceased.

Wednesday, November 13, was a fair day, but not clear. We were up betimes and pushed on. The amount of rain fallen was large, the roads muddy and slippery, the foliage once more bright and clean. The storm had been snow back on the mountains. We pushed on to St. Helena that day, where Professor Whitney and Hoffmann left us, going on by stage.

Thursday, November 14, we had some rain, but not much, and we made a long march, stopping at Suscol once more. We had landed on the shores of California just a year ago this day and had intended to celebrate it, but our only celebration was sundry glasses of larger and punch in the evening, which was dark and rainy. It rained most of the night, and at morn it had not ceased. So we took our breakfast at the neighboring “hotel”—there are no “taverns” here—loaded up in the rain and pushed on. Luckily I had an old overcoat, one left by Hoffmann, which protected me much. It continued to rain much of the way to Benicia, where we arrived at 2 P.M. It was uncomfortable enough—roads muddy and slippery, the deep dust of two weeks ago slippery mud now, a drizzling rain in our faces as we plodded on our slow way.

At Benicia we put all our things in the wagon, harness and all, and I sent Averill and Peter on to Clayton at the foot of Mount Diablo, with the mules, where they are to be kept during the winter. That night Mike and I took the steamer for San Francisco, bringing the wagon along. It lacked only a week of a year that we had been actually in the field.

Then came getting ready for office work, clearing up, etc. And now we are fairly at work—and irksome enough it is, I assure you. To sit down in the office, write, compare maps, make calculations, and plot sections, is harder work than mountain climbing. I begin to long for the field again—were it not so wet, for it has rained much since.

A few items in summing up. I have been the entire year in the Coast Range between San Bernardino and Clear Lake. The Coast Range is not a single chain, nor even parallel chains, but a system, radiating, like the spokes of a wheel, from a point near the great mass of San Bernardino.9 I find on looking at my notes, that since taking the field I have traveled 2,650 miles on my mule; 1,027 on foot, and 1,153 by other means—total in the field, 4,830 miles. During the same time my letters, official and otherwise, have amounted to just 1,800 pages (note size), of which 604 (including this letter) were my “Home Journal,” and about 400 were my letters to Whitney reporting progress, etc. In addition to this, over a thousand pages of “Field Notes” of about the same size—some writing to do amid the inconveniences of camp life, surely! These figures will show that I have not been entirely idle, as the data are strictly accurate.

Last Saturday my friends, Blake and Pumpelly, sailed for Japan. They go at the invitation of the Japanese Government, to aid in developing the resources of the mines in Japan. Blake stuck hard to have me go with them, but my place looks too secure here, and that looks precarious. Had I been free I would have rejoiced at the chance.

On the other hand, some most influential men of the state want me to go as commissioner to London next spring, in charge of the California collections at the World’s Fair. There is much scrambling and wirepulling for the office of commissioner, but I could get it if I would put in. But the Survey here is a surer thing for me. I have proved myself capable of successfully managing a party, carrying it through times of discomfort, and even hardship, accomplishing much labor, and doing it economically. Whitney feels that I cannot be spared here. I have assurance that should our appropriation next year be cut down I will be the last man discharged—that is, should it be too small to keep a larger party in the field, I will have my place if no one else stays but Whitney. All this is very gratifying, for the actions of legislatures in such matters are very uncertain. We will, of course, get some appropriation, it remains to be seen how much. The present tardiness in paying us up is most unfortunate. It is a very great inconvenience. Even the Governor has not been paid any salary since May last. We hope for better things soon.

I have a pleasant room, hired by the month, and eat my meals at restaurants. I may take board by the week soon—am not yet decided.

Thankful to an overruling Providence who has thus far guarded me and kept me in times of danger—this is Thanksgiving night—I have just returned from a dinner at Professor Whitney’s.

NOTES

1. Serranus Clinton Hastings (1814-93) was a native of Jefferson County, N. Y. He lived for a time in Indiana, then in Iowa, where he became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court after serving a term in Congress. He came to California in 1849 and settled at Benicia. He was immediately appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of California (1849-51). In 1851 he was elected Attorney-General and served two years. Turning to business and the practice of law, he made a large fortune from lands and was reputed to be worth nearly a million dollars in 1862. He founded the Hastings College of Law in 1878. His wife, Azalea Brodt, of Iowa, died in 1876. They had four sons and four daughters (History of the Bench and Bar of California, ed. Oscar T. Shuck [Los Angeles, 1901

2. The name Sebastopol was retained until about 1867, when it gave way to Yountville. There is a Sebastopol in Sonoma County, with which this place should not be confused.

3. George Yount was one of the outstanding American pioneers in California in the period preceding the gold discovery. He was born in Burke County, North Carolina, 1794, whence the family moved to Missouri. He enlisted in the War of 1812 and then, and subsequently, engaged in Indian fighting. After several years of farm life in Missouri, during which he married and had children, he set out for the west and engaged in trapping. He was with the Patties on the Gila in 1826, and came to California with Wolfskill in 1831. After hunting sea otter near Santa Barbara, he came to San Francisco Bay and settled for a time at Sonoma, where he became acquainted with M. G. Vallejo. He obtained a grant of land in Napa Valley, the Caymus Rancho, which was confirmed in 1836. To obtain land it was necessary to be baptized a Roman Catholic, and it was thus that he obtained the middle name Concepción. He died at the Caymus Rancho in 1865 and was buried at Yountville with Masonic honors (“The Chronicles of George C. Yount,” ed. Charles L. Camp in the California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. II, No. 1 [April, 1923]).

4. Joseph Henry (1797-1878) of Princeton and of the Smithsonian Institution. The name was never adopted and the mountain is now known as St. John Mountain (2,370 feet).

6. The maps referred to were probably editions of Colton’s Map of California, published from 1855 to 1860. Much of the detail of the Colton maps agrees with that on Goddard’s map, published by Britton & Rey, San Francisco, 1857. The Whitney Survey added something to the topographical knowledge of this region, but even today there are no reliable maps of the portion of California north of Sonoma and Napa counties.

8. The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey gives the height as 4,338 feet. The first known ascent was in 1841, when a party from the Russian settlement at Fort Ross visited the mountain and gave it its name. For several years there was on the summit a metal plate bearing the names of Wossnessenski and Tchernich, with the date 1841. Dr. W. A. Wossnessenski was a naturalist traveling under auspices of the Russian Government; E. L. Tchernich was proprietor of a ranch at Bodega Bay. In one account it is said that Princess Helena de Gargarine accompanied the party to the summit and that she christened the mountain for her aunt, Helena, the Czarina. It is somewhat of a speculation as to whether the name should be Mount Helena, as named for the Czarina, or Mount St. Helena, as named for her patron saint (Honoria Tuomey and Luisa Vallejo Emparán, History of the Mission, Presidio, and Pueblo of Sonoma [1923]; History of Napa and Lake Counties, California [San Francisco, 1881]; Whitney Survey, Geology, I, 86-87).

9. This conception is erroneous; more extensive knowledge later disclosed a different relationship.

| Next: Book 3 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 5 |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/2-6.html