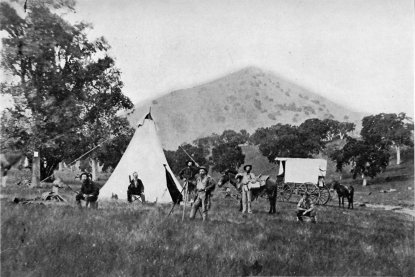

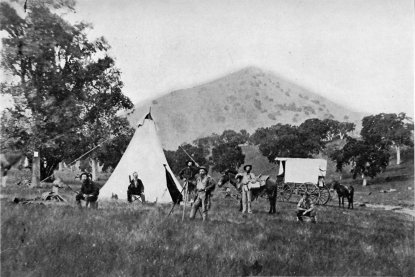

THE SURVEY PARTY IN CAMP NEAR MOUNT DIABLO, 1862

GABB WHITNEY AVERILL HOFFMANN BREWER SCHMIDT

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > 1862 Chapter 2 >

| Next: Chapter 3 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 1 |

Mount Tamalpais—Sausalito—Marin County—Spanish Grants—Patriotic Outbursts—Sonoma County—Stockton—Lunatic Asylum—In Camp Again—With Starr King on Mount Diablo—A Vast Panorama—Alone on the East Peak—Mighty Oaks—The Story of Mr. Marsh.

In Camp, near Martinez.

April 27, 1862.

For three weeks I have been too much occupied to write journal so am more than a month behind, but I am once more in camp and hope to have time now to bring it up. We went into camp four days ago, Wednesday, April 23, for the summer.

We are at present at work on a map of the portion of the state lying about San Francisco Bay—north to Petaluma and Napa, south to the quicksilver mines of New Almaden, east to beyond Mount Diablo, and west to the ocean—a very small portion of the state, but an important region, embracing some 4,500 square miles (about 3,000 square miles of land) in the heart of the state. We did much work on it last year and want to finish it and publish it along with other work this year. The region lying north of the Golden Gate and the bay could be best looked up on foot, and Hoffmann and I did it after spring opened, while the rest were at work in the office.

Wednesday, March 26, Hoffmann and I started, with compasses, barometer, etc.—an unpleasant day and rainy evening. We went up to San Rafael, about twenty miles north of San Francisco. The following day we struck back into the hills a few miles and stopped all night at a ranch-house. The man was absent, but his wife, a Boston lady, who showed much intelligence and even refinement, was at home and hospitably entertained us. She was of the prettiest women I have seen in this state.

The whole region between the bay and the sea is thrown up into rough and very steep ridges, 1,000 to 1,600 feet high, culminating in a steep, sharp, rocky peak about four or five miles southwest of San Rafael, over 2,600 feet high, called Tamalpais. On this was once a Coast Survey station, an important point.1

On March 28 we were up early and were off to climb this peak. A trail led through the chaparral on the north side. We reached the summit of the ridge, got bearings from one peak, and started along the crest of the ridge to the sharp rocky crest or peak. The wind was high and cold, fog closed in, and then snow, enveloping everything. We were in a bad fix—cold, no landmark could be seen—to be caught thus and have to stay all night would be terrible, to get off in a fog would be impossible. We waited behind some rocks for half an hour, when it stopped snowing and the fog grew less dense; we caught glimpses of the peak and started for it.

The last ascent was very steep. We climbed up the rocks, and just as we reached the highest crag the fog began to clear away. Then came glimpses of the beautiful landscape through the fog. It was most grand, more like some views in the Alps than anything I have seen before—those glimpses of the landscape beneath through foggy curtains. But now the fog and clouds rolled away and we had a glorious view indeed—the ocean on the west, the bay around, the green hills beneath with lovely valleys between them.

We got our observations, remained two hours on the summit, then started for Sausalito,2 eight or ten miles in a direct line south. It was a hard walk, over hills and across canyons—our distance was doubled. It was long after dark before we found Sausalito, where we stopped at an Irish hotel. We ate a hearty supper, then sat in the kitchen and warmed and talked. Hogarth never sketched such a scene as that. The kitchen, with furniture scattered about, driftwood in the corner, salt fish hanging to the ceiling and walls, lanterns, old ship furniture, fishing and boating apparatus, a Spanish saddle and riata—but I can’t enumerate all. Well, we stayed there all night and for several hours the next morning, then took a small boat for San Francisco, along with a load of calves and pigs piled in the bottom.

Sausalito is a place of half a dozen houses, once “destined” to be a great town; $150,000 lost there—city laid out, corner lots sold at enormous prices, “water fronts” still higher—for a big city was bound to grow up there, and then these lots would be worth money. The old California story—everybody bought land to rise in value, but no one built, no city grew there. Half a dozen huts and shanties mark the place, and “corner lots” and “water fronts” are alike valueless. This was on the same ranch with “Lime Point,” where $400,000 was asked of Uncle Sam for a spot of land worth $100 at the highest figure, to build a fort on, but never bought.

April 4 we started on our second trip. We went up by steamer to near Petaluma,3 forty-five miles north of San Francisco, then struck back over the hills toward San Rafael, climbing all the principal ridges, getting the geological data and notes for a correct topography. We were in the hills three days, and hard days they were. From the summits of these steep hills we got some most magnificent views, while many of the valleys are perfect gems of beauty, nestled among these rugged hills. The finest grazing district I have yet seen in the state is among these hills, lying near the sea, moistened by fogs in the summer when the rest of the state is so dry. But the curse of Marin County is the Spanish grant system. The whole county is covered with Spanish grants, and held in large ranches, so settlers cannot come in and settle up in smaller farms. The county is owned by not over thirty men, if we except men who have small portions near the bay or near some villages. As a consequence, there is but one schoolhouse, one post office, etc., in the whole county, although so near San Francisco.

From the County Surveyor’s map I find that there are 330,000 acres of land in the county, of which less than 2,000 acres were ever public lands—in fact, only 1,500 acres besides some little islands. The rest of the county is covered by twenty-three “grants” of which seventeen are over 8,000 acres each! I will give the size of a few of these grants, or ranches, which I copied from the map named—13,500 acres, 21,100, 15,800, 56,600, 48,100, 21,600, 19,500, 13,500, 23,000, 12,200, and so on, but the rest are under 10,000 acres. No wonder that the country does not fill up.

We returned to San Francisco April 8 and remained until April 14. In the meantime, at ten o’clock Saturday night, April 12, came the news of the battle at Pittsburg Landing, supposed to be a much greater victory than it really was.4 Such an excitement in the streets. People were out, at midnight a salute of cannon was fired, and the streets were as noisy all night long as if it had been Fourth of July. A great concert was in progress, the oratorio Creation, when the dispatch was read on the stage. The music stopped, people cheered, wild with excitement, Yankee-Doodle and The Star-Spangled Banner were sung and played—probably the first time those pieces were ever introduced in that sacred oratorio.

Sunday was a day of excitement and rejoicing. From Telegraph Hill, an eminence on one side of the city, someone counted 356 flags floating in the stiff breeze, besides the multitudes of small flags, too inconspicuous in size to be noticed. T. Starr King delivered a patriotic sermon that night, the anniversary of the fall of Fort Sumter, which, although probably hardly appropriate for Sunday, was nevertheless a most brilliant and eloquent performance. The crowded church could scarcely be restrained from bursting out in enthusiasm during some passages.

Monday, April 14, Hoffmann and I started off for another trip. We went up to Petaluma, spent two days there, then footed it across the ridges to Sonoma, then across to Napa—a most interesting but laborious trip.

A valley extends north from Petaluma to the Russian River—a mere low range of hills, scarcely perceptible, separating the Petaluma and the Santa Rosa valleys. They are of exceeding beauty at this time of the year, and both Petaluma and Santa Rosa are thriving villages surrounded by rich farming lands. From the high hills between Petaluma and Sonoma villages, a most beautiful view can be had of all these valleys, the bay, Mount Diablo, and the region south. We enjoyed these views much.

Sonoma Valley, north of San Pablo Bay, is surrounded by high hills on three sides, and is a plain running up a number of miles, as if San Pablo Bay once occupied the ground, as it probably did in earlier times. Sheltered from the winds by high ridges on the west and north, the climate is milder than most other places on the bay, and is now obtaining some considerable renown for its vineyards and its wines.

From Sonoma we kept on east toward Napa, but did not go quite to the latter place, but returned to Sonoma, crossed the hills by stage to Petaluma Creek and returned by steamer to San Francisco. All the places I have mentioned are on your map, north of the bay.

But in speaking of these trips I forgot quite an item. I had been invited to lecture in Stockton on the evening of April 10, and went up the night before, arriving that morning. I was well received, hospitably entertained, and had a good time generally—got tall puffs in the three daily papers for my lecture.

The State Lunatic Asylum is there, and as the trustees were to have a meeting, I was invited to go up, which I did, and spent several hours visiting the institution while they were transacting their business. There are more insane in this state, by far, in proportion to the whole population, than in any other state in the Union. I need not dilate on the reasons. High mental excitement, desperate characters, disappointed hopes of miners, the unnatural mode of life incident to mining, separation of families, and the indiscretions and infidelity to the marriage vows incident to these separations—these and other reasons have produced this frightful result.

Four hundred and thirty unfortunates are crowded into this institution, only intended to accommodate two hundred and fifty. The proportion of men is more than twice as great as women—there were over three hundred men there. Near two hundred were out in a great yard, surrounded by high brick walls, in the warm, bright, spring sun—some lolling on benches, some talking, swinging on ropes in a sort of gymnasium, “speechifying,” singing, praying, etc. Some were sullen and silent, some talkative, some bombastic, some modest.

One spoke to me in German and was delighted to hear me answer in the same tongue. He announced that he was the Emperor of Austria, but was illegally deprived of his liberty here, that Queen Victoria wished him to marry one of her daughters—all of which he told me over and over and besought earnestly my assistance is helping him obtain his rights. He followed me closely for half an hour, closely imitated my actions in everything I did, and before I left the building I heard he had formally applied to the keeper of his ward for permission to accompany me to England.

We went up to the tower and enjoyed a perfectly magnificent prospect. The great plain around Stockton is some forty or fifty miles wide from east to west, and to both the north and south stretches to the horizon, literally as level as the sea and seeming as boundless. In the west and southwest lies the rugged Mount Diablo Range, to the northwest lie the ranges north of Napa, while along the eastern horizon the snowy “Sierras” (Sierra Nevada) stretch away for a hundred miles, their pure white snows glistening in the clear sun.

That evening I lectured—had a good house for so small a

THE SURVEY PARTY IN CAMP NEAR MOUNT DIABLO, 1862 GABB WHITNEY AVERILL HOFFMANN BREWER SCHMIDT |

Next day they pressed me to receive fifty dollars for my lecture. I can receive nothing, of course, for any outside services while in my present position. I refused all except traveling expenses. They insisted and I refused—at last they paid my traveling expenses, gave me a very neat meerschaum camp pipe (worth ten dollars) and fifteen dollars toward the botanical wants of the Survey. This was evidence enough that my “effort” was appreciated. I came back April 11, delighted with my trip, and already my “meerschaum begins to color.”

Tuesday last, April 22, I sent on the party to go into camp here, near Martinez, and I followed the next day. Our party consists of: Averill, who goes as mule driver, clerk, etc.; Hoffmann, topographer; Schmidt, our new cook, who promises well; Gabb,5 our paleontologist, young, grassy green, but decidedly smart and well posted in his department—he will develop well with the hard knocks of camp; Rémond,6 a young Frenchman, who will be with us for about two weeks. We commenced by drinking a bottle of champagne presented by a young lady of San Francisco.

Well, for three days we have been hard at work here and expect Professor Whitney up tomorrow to join us. The hot sun begins to tell on the faces, necks, and hands of the party. Rémond’s nose looks like a strawberry, red and fiery. Hoffmann’s is like a well-developed tomato, while Gabb’s nose is today more like the prize beet at an agricultural fair. Skins are red, faces burned, necks more scorched, but I think all will come out right in a little while.

Camp 70, near Mount Diablo.

May 18.

Professor Whitney joined us, and on Wednesday, April 30, we moved about nine miles up the valley, south. The next day Hoffmann and I visited a ridge about two thousand feet high, about six miles from camp, quite a hard day’s tramp. Heavy clouds wreathed the whole summit of Mount Diablo, but we had a fine view of the green hills near and around us. A shower caught us on our return and wet us, but how unlike the rains of the city. The smell of the rain on the fresh soil and green grass was decidedly refreshing.

That night the wind was high, and for three days we had intermittent but heavy rains. We stuck to our tents, but on Friday, May 2, Professor Whitney left for San Francisco. It rained too hard to cook outdoors, so that day and Saturday we got our meals at a tavern near. On Sunday, May 4, we got a fire lit and dinner half cooked when a heavy shower put it out. We went to the tavern again. In the afternoon there was less rain and I sent Averill to Pacheco, seven miles, for letters.

The rain was a godsend to the farmers. The soil had begun to bake and crack so that the growing grain could not get on farther. Everything has “greened up” marvelously, and this region, so brown, dry, dusty, and parched when we visited it last fall, is now green and lovely, as only California can be in the spring. Flowers in the greatest profusion and richest colors adorn hills and valleys and the scattered trees are of the liveliest and richest green.

Tuesday, May 6, the camp came on here, about ten or twelve miles. I waited to observe barometer to get the height of the camp above the sea, then footed it across here, a part of the way across hills, the rest across the Pacheco Valley, a plain of many thousand acres, several miles wide, sloping gently from Mount Diablo northwest to the Straits of Carquinez.

The plain is covered for miles with intervals of scattered oaks; not a forest, but scattered trees of the California white oak (Quercus hindsii), the most magnificent of trees, often four to five feet in diameter, branching low. They are worthless for timber, but grand, yes magnificent, as ornamental trees, their great spreading branches often forming a head a hundred feet in diameter. Across this great park the trail ran.

On arriving I found the camp pitched in one of the loveliest localities, a pure rippling stream for water, plenty of wood, fine oak trees around, in a sheltered valley, but with the grand old mountain rising just behind us.

Professor Whitney had met us, and a party was here from San Francisco to visit us and climb the mountain. A little town, consisting of a tavern, store, etc., is rapidly growing up scarce twenty rods from camp, where a “hotel” accommodated them. The party consisted of Rev. T. Starr King, the most eloquent divine and, at the same time, one of the best fellows in the state, Mrs. Whitney, Mr. and Mrs. Tompkins (a lawyer whose wedding I had attended last winter), Mr. Blake7 (a relative of Mrs. Whitney and an intimate friend), and a Mr. Cleaveland (one of the officers in the United States Mint)—a better party could not have been selected.

That evening, a lovely moonlight May evening, we lighted a great camp fire, and our visitors enjoyed it, so new to them, ever so charming to us. The moon lit up the dim outline of the mountain behind, while our fire lit up the group around it. We “talked of the morrow,” spun yarns, told stories, and the old oaks echoed with laughter.

Wednesday, May 7, dawned and all bid fair. We were off in due season. I doubt if there are half a dozen days in the year so favorable—everything was just right, neither too hot nor too cold, a gentle breeze, the atmosphere of matchless purity and transparency.

Five of our party, Professor Whitney, Averill, Gabb, Rémond, and I, accompanied our visitors. They rode mules or horses; we (save Averill, who was to see to the ladies) went on foot. First, up a wild rocky canyon, the air sweet with the perfume of the abundant flowers, the sides rocky and picturesque, the sky above of the intensest blue; then, up a steep slope to the height of 2,200 feet, where we halted by a spring, rested, filled our canteens, and then went onward.

The summit was reached, and we spent two and a half hours there. The view was one never to be forgotten. It had nothing of grandeur in it, save the almost unlimited extent of the field of view. The air was clear to the horizon on every side, and although the mountain is only 3,890 feet high, from the peculiar figure of the country probably but few views in North America are more extensive—certainly nothing in Europe.

To the west, thirty miles, lies San Francisco; we see out the Golden Gate, and a great expanse of the blue Pacific stretches beyond. The bay, with its fantastic outline, is all in sight, and the ridges byond to the west and northwest. Mount St. Helena, fifty or sixty miles, is almost lost in the mountains that surround it, but the snows of Mount Ripley (northeast of Clear Lake), near a hundred miles, seem but a few miles off. South and southwest the view is less extensive, extending only fifty or sixty miles south, and to Mount Bache, seventy or eighty miles southwest.

The great features of the view lie to the east of the meridian passing through the peak. First, the great central valley of California, as level as the sea, stretches to the horizon both on the north and to the southeast. It lies beneath us in all its great expanse for near or quite three hundred miles of its length! But there is nothing cheering in it—all things seem blended soon in the great, vast expanse. Multitudes of streams and bayous wind and ramify through the hundreds of square miles—yes, I should say thousands of square miles—about the mouths of the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers, and then away up both of these rivers in opposite directions, until nothing can be seen but the straight line on the horizon. On the north are the Marysville Butters, rising like black masses from the plain, over a hundred miles distant; while still beyond, rising in sharp clear outline against the sky, stand the snow-covered Lassen’s Buttes, over two hundred miles in air line distant from us—the longest distance I have ever seen.

Rising from this great plain, and forming the horizon for three hundred miles in extent, possibly more, were the snowy crests of the Sierra Nevada. What a grand sight! The peaks of that mighty chain glittering in the purest white under the bright sun, their icy crests seeming a fitting helmet for their black and furrowed sides! There stood in the northeast Pyramid Peak (near Lake Bigler), 125 miles distant, and Castle Peak (near Lake Mono), 160 miles distant, and hundreds of other peaks without names but vieing with the Alps themselves in height and sublimity—all marshaled before us in that grand panorama! I had carried up a barometer, but I could scarcely observe it, so enchanting and enrapturing was the scene.

Figures are dull, I admit, yet in no other way can we convey accurate ideas. I made an estimate from the map, based on the distances to known peaks, and found that the extent of land and sea embraced between the extreme limits of vision amounted to eighty thousand square miles, and that forty thousand square miles, or more, were spread out in tolerably plain view—over 300 miles from north to south, and 260 to 280 miles from east to west, between the extreme points.

We got our observations, ate our lunch, and lounged on the rocks for two and a half hours, and then were loath to leave. We made the descent easily and without mishap or accident—a horse falling once, a girth becoming loose and a lady tumbling off at another time, were the only incidents. The shadows were deep in the canyon as we passed down it, but we were back at sunset. Our friends were tired, some of them nearly used up. With us, the day was not a hard one.8

The party sat rather silent by the cheerful camp fire that evening, some through fatigue, others from thought, but all seemed happy. Tompkins was the most fatigued, in fact, nearly used up. Next day he said to me, half confidentially, “Last night I felt humiliated, much so. I had ridden most of the way up the mountain and back again and was so nearly used up that I could have gone but little farther. You went up on foot, carried a barometer, picked out trails for us, and did the work, and came back apparently as fresh as when you started.” I told him he must enjoy the luxury of camp life, sleep on gravel stones, put off his “boiled shirt,” and come down to bacon and beans, to really enjoy life and health.

Thursday, May 8, was a cool blustery day and most of our company left for San Francisco. Mrs. Whitney and Mr. Blake left the last of the week, dining with us the last day. We were up the mountain in the “nick o’ time,” for it has not been perfectly clear since, and three days after our first ascent the mountain was white with snow, and snow remained on it for three days. We had very cold weather, especially nights.

We continued our work in this region. Although Mount Diablo is the initial point of all surveys for this part of the state, yet, strangely enough, its topography had not been mapped. Nor was the geology at all understood, although it is a most important spot as furnishing a key to many formations of the state, and of great pecuniary interest from the fact that the only coal mines worked to any advantage in the state are on the north side of the mountain and within five miles of the summit.

Last week we spent in exploring and examining. We climbed the mountain twice, once passing over it to the south and west sides, another time crossing the crest to the east peak, lower by three hundred feet than the main peak, but rocky and almost inaccessible. Its views were the more picturesque. Both days the Sierras were veiled in clouds and the distant view shut out, but all within forty or fifty miles, an area of ten thousand or twelve thousand square miles, was in perfectly plain view.

I cannot detail each day’s work, and were I to do it you would find much sameness in the pictures, for all would be of the same or similar scenes. Yesterday Professor Whitney left for San Francisco to try and raise some money. Our state legislature has lately adjourned, and a distinguished state senator, Mr. Banks, from San Francisco, came up here two days ago. Yesterday he came to camp, took dinner with us at 5 P.M. and spent the evening. Several others came in, and we had a jolly time.

Today has been a very quiet day. We pitched the tent in a new place this morning, for the grass was worn out in the old site and we needed a “new carpet.” The boys went down to town, but a few rods distant, where a new brewery has just been started, bought a barrel of lager, brought it up in a wheelbarrow, and it reposes under a tree. Now they are out by the camp fire—it is evening—and have drawn a pail of it. I look out and see them lying around, each with his pipe and basin of beer; the bright blaze lights up the scene, and makes it one fit for a painter.

Livermore Pass.

June 1.

We remained at work in the Mount Diablo region until the twenty-eighth of May. I resolved to make another measurement of the mountain for the sake of seeing where some errors lay in our previous measurements, and also to determine the altitude of the northeast peak, which we have named Mount King.9 So that morning I started, with Averill and two barometers, leaving Hoffmann at camp to observe station barometer. A citizen went with us to find the trail, for the people of Clayton have resolved to spend a hundred dollars in making the trail passable for “travelers,” to attract visitors.

The morn was gloriously clear, but before arriving at the summit cold winds and clouds came on, which hung over the summit at intervals during the day. There are two peaks, one about three hundred feet below the other, and between them a gap. Leaving Averill on the main peak, I descended into the rocky gap over eight hundred feet below. Through this gap the wind roared with a violence almost terrific at times—the temperature only 44° to 46°—and at intervals the clouds rushed through like a torrent. I spent an hour and a half, observing every fifteen minutes, in that peculiarly grand spot—not grand because of the view, but because of the surrounding rocks and the clouds which rushed among them, dissolving again after leaving the mountain, driven by the fierce wind that was concentrated by coming up a canyon that had its head in this gap.

Then I took my way along the crest to Mount King. It is but half a mile from the gap, but it is a crest of naked rocks, over and among which one has to pick his way, not always without danger. I spent two and a half hours in observations. The wind was not so high, and the clouds enveloped me only once, but they hung much of the time over the main peak where I had left Averill and our companion.

I shall never forget those hours. The solitude—total silence save the howl of the winds in the gap below—the cragged rocks around me, and the enchanting scene spread out below—the great San Joaquin plain seeming more like a sea than ever—cloud shadows chasing each other over the green hills at the base of the mountain—and the clear blue sky in the southeast beyond the reach of the clouds that formed over our summit. The distant Sierras were in view, but not with that distinctness with which we saw them before.

I got back to the other peak, joined my shivering companions, and we were back before sunset, tired enough. But we were to leave the next morning and a month would elapse before I could mail letters again, so after making calculations, I wrote until midnight.

We have made five measurements, but have discarded two that were made under the poorest circumstances, saving only the best. Let me tell you how they agree: height of Mount Diablo above mean tide—(a) 3,879.6, (b) 3,876.0, (c) 3,874.1: mean 3,876.4 feet.10 These three measurements varied less than five and a half feet, from the lowest to the highest, although the distance from the summit to the tidewater (at Martinez) must be over fifteen miles. We have made a most accurate observer of Averill. These measurements are the result of eighty-two barometrical observations, and not less than three hundred have been taken on all our work in this vicinity.

Wednesday, May 28, we came on, but neither letters nor money had arrived. So I left Gabb at Clayton. We went on to Marsh’s, about fourteen miles east. The road led down a canyon torn by last winter’s floods. The road was considered passable, but one not used to our life would pronounce it utterly impassable for any wagon, yet we brought our wagon through with only one slight break, making the fourteen miles in four and a half hours.

Before the canyon emerges into the San Joaquin plain it winds into a flat of perhaps two or three hundred acres surrounded by low rolling hills and covered with oaks scattered here and there, like a park. And such oaks! How I wish you could see them—nearly worthless for timber, but surely the most magnificent trees one could desire to see. I measured the circumference of about thirty, near camp, that were over fifteen feet around three and a half or four feet from the ground—eighteen, nineteen, or twenty feet are not uncommon—with wide branching heads over a hundred feet across—one was seven feet in diameter with a head a hundred and thirty feet across.

Well, Gabb did not arrive with letters and funds until Friday night. In the meantime we examined the region about there and got acquainted with Mr. Marsh. I promised you something of this man’s history last fall, and I will now give the facts gleaned from several sources—some of the main ones from him himself, the rest from reliable authorities.

Doctor Marsh was born in Massachusetts, graduated at Harvard University, spent some time in Canada, Wisconsin, Illinois, and other western territories at an early day, and finally, in the employ of the American Fur Company, came here to California in 1836, just after the confiscation of the missions by the Mexican Government, and bought a large ranch on the east side of Mount Diablo. Here he lived, and later married a Boston lady who came to this state. He had various adventures, was robbed, had all the experiences incident to the life of a wealthy ranchero here in early times, counted his cattle by the tens of thousands, and lived like a patriarch.11

Sometime in the summer of 1856 he was a little unwell, and, while he was reclining on a bed in his sitting room, a seedy, tired, hungry looking man entered, late in the evening, and wished to stay all night. The man was an American, and the Doctor, suspicious of his countrymen, especially of such looking men, refused to keep him.

“But, Sir, I am tired—have lost my way—I saw a light here and came in.”

“Have you any money?”

“No.”

“A man has no business to be traveling here afoot and alone, without money.”

“I can’t help that. I am tired—my feet are sore. The great Joaquin plain lies beyond, as I hear, without houses—I don’t ask for money, not even food, nor a bed—let me lie before the fire.”

At last the wealthy doctor gave his consent and began various inquiries.

“Where are you from?”

“San Francisco—just out from the States.”

“What State?”

“Illinois.”

“What is your name?”

“Marsh.”

“Marsh?”

“Yes, Marsh.”

“Marsh—from Illinois? Where were you born?”

“Wisconsin.”

“What county, and when?”

In the meantime, the doctor, becoming interested, rose up from the bed and sat upon the edge. A few more questions were asked in quick succession, much to the astonishment of the traveler.

“Pull off your boot,” says the doctor. “Now your stocking.”

It was done, disclosing two toes grown together to their ends.

“Man—you can stay, for you are my son. I supposed you died a boy!”

The doctor, while in Canada, had taken a French mistress, who had gone with him to the western states. By her he had two children, a boy and a girl. While he was absent he heard of her death and that of the children. The mother and daughter did die, but not the boy, who was brought up by a Kentucky farmer in Illinois.

He married, lived a poor man, and finally came to California in 1856 to seek his fortune, as one account says, or to seek his father, of whom he had accidentally heard—the latter is probable. However, he arrived, poor, friendless, landed in San Francisco, started in the search, lost his way, saw a light, went to it, and found it to be that of his father’s house.

The old man kept him for a time, merely as a hand on his ranch—I think about four to six months—when the old man was murdered by some Spaniards.

Young Marsh threw in his claim for his share in the ranch, that he was a legitimate son, etc. After much legal investigation, a Roman priest from Montreal testified to the fact that Marsh had called this woman his wife. Other witnesses were found who declared that Marsh had introduced her as his wife. They had lived in a region where magistrates were few and far between, and marriages were not always solemnized in that way to be legal. Well, he got the ranch, sharing the property with a half-sister by the second wife, a girl now ten years old.

Here are the facts for you to build a romance upon—the long separation, the strange meeting, the murder of the old man by which this before-neglected man (I was about to say outcast) so soon became rich, coming here at just the right time.

He has a beautiful ranch—the old man claimed eleven leagues, but only three leagues, or over 13,300 acres, were confirmed—with the finest ranch-house I have yet seen in the state.

But here, for the sake of romance, let the facts stop—do not let me go on and tell how the present occupant is a boor—how old chairs with rawhide bottoms occupy rooms with marble mantles, how the fine mansion is surrounded with a most miserable fence, with hogs in the yard, some of the windows broken, and things slovenly in general. Such is the true story.

Well, yesterday morning we left that camp. The morning was clear and warm, and as we came out on the plain, in the hot sun, a beautiful mirage flitted before us—the illusion was perfect. It seemed as if a marshy lake lay along ahead of us, a few miles off. Often the trees were reflected as perfectly as if it were really water, but on approaching, it would keep away from us. About noon the wind rose, however, and with it the mirage left the plain.

We passed on beyond the trees and came into camp here, a camp as unlike the last as day is unlike night—among foothills utterly treeless—before us stretching the plain, also treeless, not a bush even greeting the eye for many miles. From a nearby hill yesterday we could look over an area of at least two hundred square miles and not see a tree as far as the river, where, ten miles off, there is a fringe of timber along the stream. The hills are already brown. Over them swept a fierce wind and it took all hands to get the tent pitched. All night long the wind howled, the tent shook and rattled, nor has it ceased today, although tonight it is less.

NOTES

1. The height of the east peak is 2,586 feet; that of the west peak is 2.604 feet (U.S.G.S.). The Coast Survey station was on the west peak. The early Coast Survey reports call it Table Mountain. Tamalpais is a local Indian name—Tam-mal (bay country) and pi-is (mountain).

2. Brewer spells it Saucelito, an erroneous form current for a short time. Sausalito is Spanish for “little willow grove” (Nellie Van de Grift Sanchez, Spanish and Indian Place Names of California [2d ed., San Francisco, 1922]).

4. The dispatches called it “the bloodiest battle of the age.” It was reported that fifty thousand were killed.

5. William More Gabb (1839-78).

6. Auguste Rédmond died in June, 1867.

8. Starr King’s glowing account of this day will be found in Charles W. Wendte, Thomas Starr King: Patriot and Preacher (1921), p. 126.

9. This name for the east peak has not persisted. Starr King’s name has, however, been established on a dome above Yosemite Valley.

10. In the Whitney Survey, Geology (1865), I, 10, the height is given as 3,856 feet. The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey figure is 3,849.

11. The episode of Dr. Marsh and his son is corroborated from other sources. John Marsh (1799-1856) was born in Danvers, Mass., and was a member of the class of 1823 at Harvard. He lived for a while at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, and at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, but not in Canada. Later he went to Missouri and to Santa Fè. In 1836 he moved to Los Angeles and was the first man to practice medicine there. In 1837 he came to San Francisco and for a year explored in the northern part of California. In 1838 he purchased the ranch near Mount Diablo, where he became, with Sutter, Yount, and a few others, one of the outposts of civilization. (Information from Dr. George Lyman, San Francisco.)

| Next: Chapter 3 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 1 |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/3-2.html