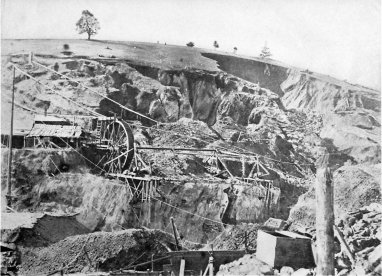

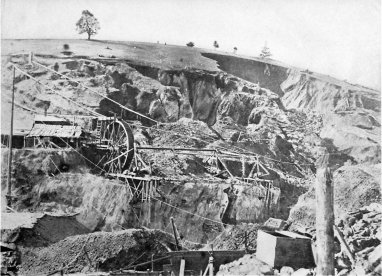

HYDRAULIC MINING

From a photograph by Don Rafael Ordoņez Castro, of the

Pacific Squadron of Spain, 1863

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Up & Down Calif. > 1862 Chapter 7 >

| Next: Book 4 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 6 |

Tomales Bay—An Irish Spree—Tomales Point—A Long Walk to San Rafael—The Alameda Hills—Penitentia Canyon—Summary of the Year—Continued Financial Troubles—Wreck of the Paul Pry—Earthquake—Christmas Amenities—Contrasts.

San Francisco.

November 30, 1862.

November has been a month of most lovely weather—no rain here, save one or two slight showers, air generally clear, although often foggy in the morning, so warm that I have not had any fire in my room over three or four times, free from the intense winds of summer—in short, lovely weather.

I have been in the office a part of the time, and the rest occupied in excursions in the regions about the Bay of San Francisco. My health has been most excellent. My sickness in the summer, although more severe than that which afflicted any of the other members of the party, was not so lasting in its effects. I have long been entirely well. But Hoffmann came back to the city in a sad plight; he looked bad when we returned—pale, weak, haggard—but looks much better now. Schmidt was taken down again, and went to the hospital, but he has got out again. He has been out a week, but does no work yet.

I have made several foot trips in the region about the bay since the breaking up of the party. October 27 Professor Whitney and I left here and went to Benicia for a short trip in Napa and Sonoma counties. We footed it over the hills for two days, and returned to this city October 30. There was little to interest you on that trip.

November 3, with Rémond, I started for another in Marin County, northwest of here. We went up to Petaluma, and the next day went across, west, to a place known as Tomales, near the mouth of Tomales Bay. This is a region of low, rounded hills, near the sea, therefore cool. During the summer it is subjected to intense winds, so it is nearly treeless. It is the greatest place in the state for potatoes, both as regards quality and quantity. The number raised here is enormous and, as a consequence, Irishmen abound. General Halleck has a ranch near this place, which we were on.

At Tomales there are several houses, but the only one where we could get “accommodations” was a very low Irish groggery, kept by a “lady.” The place was filled with the Irish potato diggers, all as lively as the poorest whiskey could make them. One Irishman had just made some two hundred dollars by a contract for digging, and was celebrating the event, freely treating—in fact, he was just at the culmination of a three days’ spree. The “rooms” of the house were far from private, the beds not highly inviting, and the customers twice as many as the accomodations. Drunkenness, singing, fighting, and the usual noise of Irish sprees were kept up through the night. Much to my disgust I had neither “bowie” nor “Colt” along, so could not command the exemption from meddling which those companions would have insured. Now, I don’t mind the discomforts of the field, of sleeping on the ground, of diet, dust, lizards, snakes, ants, tarantulas, etc., but from drunken Irishmen, from Irish groggeries, from “ladies” of that description, “Good Lord, deliver us!”

The next morning we were off early, went to Tomales Bay, and crossed to Tomales Point. The bay is a long narrow arm of the sea that runs up into the hills, surrounded by picturesque characteristic Californian scenery. The bay is pretty, and the number of waterfowl surpassed belief—gulls, ducks, pelicans, etc., in myriads.

We were set across in a small boat, after getting some bread and meat for a lunch, which we carried along. The point is a long ridge which rises to the south, where it forms mountains, cut by deep canyons, and covered with an almost impenetrable chaparral. We footed it up south all the afternoon. The whole of this point, as well as Punta de los Reyes, is one ranch. There are a few houses on it—dairy farms, which are rented—for the chaparral peaks are only a small part of the whole, the rest is mostly fine pasturage.

Here let me give you a morsel of California ranch-land history. A Spanish grant had covered two leagues (less than nine thousand acres) which was confirmed by the United States. Although the grant was for but two leagues, mention was made of certain privileges on the sobrante or “outside lands.” Well, the lawyers (those curses of Californian agriculture), after getting the grant of 8,800 acres, then went to work and got all the rest, the sobrante, of the entire point, amounting to over forty-eight thousand acres additional, and now hold it! Before this last was confirmed to them, squatters had settled on various parts of it, especially along the bay, near its upper end. They were ejected, and the houses are now unoccupied.

This we did not know at the time. We attempted to get to a certain ranch, which at 4 P.M. was three miles distant. We got on a wrong trail in the woods and chaparral, which at night brought us down to the bay, about six miles from the head. All this part is skirted by high hills, which come down to the water, covered with an almost impassable chaparral and furrowed by steep ravines.

We came to a cabin—it was deserted and locked up. We started up along the shore—were in decidedly a bad fix. It got dark; we could not get back, for we had come over bad places we could not pass in the night. We knew not how far we could get on, but resolved to go as far as we could, for we could not camp. The tide was down, and when it rose it would cover the whole available space to the bluff. Sometimes in the soft, black, treacherous mud and water, sometimes on the sand, we pushed on. At last we struck the mouth of a canyon, saw a light in it, and found three men, woodchoppers, who had just come there, and had got into a deserted cabin. They gave us some cold potatoes and cold meat, all they had to eat, and we slept on the floor. A miserable night, but better than to have been out, for a heavy fog rolled in from the sea, and then it rained violently.

We were up long before daylight—to take advantage of the tide which was then low, for we could not get out if it rose—followed up the bay, and at nine o’clock struck a house and asked if we could get breakfast. You may well imagine that we were very hungry. The answer of the woman was, “Yes, but it will be a hard scratch.” She, however, did the best she could (who can do more?), and our appetites made up for any defect in the dishes.

We concluded to strike across for San Rafael, twenty-two miles distant. Soon after leaving the head of the bay we struck up a deep, wild canyon, exceedingly picturesque, the bottom filled with heavy timber—magnificent redwoods, often ten or twelve feet in diameter, almost shutting out the light of the sky with their dense foliage; the nutmeg tree (torreya)1; and the laurel or California bay tree, its foliage so fragrant that the whole air was often impregnated with it. But notwithstanding the beautiful way, we grew both tired and hungry, at last got some bread and pie of a Chinaman, and pursued our way. I had a heavy bag of specimens, and I was more tired when I got to San Rafael, long after dark, than I have been any other day this summer. Two nights with poor rest, three days without a decent meal, and that day we had walked from before daylight in the morning until after dark at night—no wonder that I was tired, or that I ate so much supper that I had most horrible dreams afterward.

The next day we returned to San Francisco. I then made three trips in Contra Costa County and Alameda County on the east side of the bay—one with Hoffmann, two alone. I will only tell of the last one, taken last week.

HYDRAULIC MINING From a photograph by Don Rafael Ordoņez Castro, of the Pacific Squadron of Spain, 1863 |

Last Tuesday I left here early; a dense fog hung over everything, but it cleared up before noon. I crossed to Oakland, and then rode to Haywards, near the “San Leandro” of your map, then struck across the hills to the southeast toward the Alameda Valley.

I stopped that night at a solitary cabin in the hills. A portion of a ranch, about eight hundred acres here, of hill land, cut by deep and steep canyons, is fenced in one field. On this about ninety head of cattle are kept, mostly cows.

A man is placed here to take care of them, and in the summer make butter and cheese. He has a horse to drive the cows with, a large corral, where he milks them in the season, a milk house, and a cabin to live in. This last is about twelve feet long by ten feet wide, of boards, shingle roof, one window and one door. There is a bunk on one side, of boards—a sort of crib, as it were—for a bed. Everything looks cheerless, dirty, comfortless. Here he lives, alone—he might sicken and die and no one be the wiser for weeks. Here, let me say, the tales of adventures, of hardships, and more than that, and of discomforts, that I have heard related by such men would make a big book. This man was a Norwegian, could not read English, could get no books in his own language except a Bible, so it is no wonder that he said that “te nights pe tampt long, and tis life tampt lonesome.” He got me some supper, bread of his own baking (without butter or sauce), and eggs. We talked a spell, then “retired.” As he had no extra blankets, he went out and got an old ragged piece of canvas that had been used to cover up hay with until too rotten and ragged. It was very dusty and dirty, but kept most of the cold out.

We were out before light, and I went on my way. I got into a deep canyon, then climbed a hill about two thousand feet high, commanding a most grand view, then sank into a deeper canyon, and about noon emerged into a lovely little valley—the Suņol Valley—a little plain of perhaps 1,500 or 2,000 acres, studded with scattered oaks, large and of exceeding beauty.

Here I struck another cabin, containing a woman. This cabin was, of course, far neater. She was old, but clever, and got me some dinner. The family had lived near the mouth of the canyon near, but last winter’s floods had carried off the house and all they had in it. Alameda Creek drains a large extent of country, and rose to a great river. The house was carried away in the night. The family, two men, two women, and a little girl, got into a tree, in the night, the fearful torrent roaring beneath, the rain falling in torrents. Here they remained until the next day in the afternoon when they were discovered and a rope was got to them. They were rescued by being dragged sixty yards through the water. The old lady described it as a fearful time.

Alameda Creek breaks through the hills by a canyon about six or seven miles long, and I think about 1,500 or 1,800 feet deep. The sides are very steep, rising to mountains on each side. I followed down this canyon and emerged on the plain, then footed it to Mission San Jose, and the next day returned to this city. It was Thanksgiving, and all the principal shops were closed—a great holiday. I took my dinner at my boarding house.

The fine weather still continues, but it is not probable that the rains will hold off much longer. I shall probably make one or two excursions more, but all the intervals are filled up in office work. I am now in a boarding house, but my old last winter’s quarters will soon be vacant, I hear, and I may return there, but have not decided yet.

Mr. and Mrs. Ashburner have come out, and are now here; it is pleasant to see them. He is in the employ of a banking house here, to look after their interests in various mining speculations.2

We have our old bother about getting our pay, and in the meantime we are put to much expense in consequence.

San Francisco.

December 19.

It is a dark unpleasant night, and I am blue enough over the late news from Fredericksburg. We have meager news of our terrible defeat there. We are, indeed, in a terrible struggle. Like the rest of our defeats, perhaps it arose from politicians. Whatever was the cause, it is sufficient to make one blue and sad.

The first week of this month I took a trip in the mountains east of San Jose, walked nearly a hundred miles, spent one night in a cabin where a family lived on a mountain ranch, but one room, where we all slept—man, wife, five children, and myself. I slept on the floor, the rest had beds. Surely, “half the world does not know how the other half lives.” The food was yet poorer than the other accommodations. The next day, on my way to San Jose, I attempted to explore the Penitentia Canyon, got in, could not get out except by climbing a bank one thousand feet high and fearfully steep. I had to walk twelve miles after it, with a heavy bag of specimens, and the exertion of the climb and the walk after lamed me for a week.

Well, the field work for the year has ceased. I have been adding up my “peregrinations” in this state since I arrived twenty-five months ago, and the following are the figures:

| Mule back | 3,981 miles |

| On foot | 2,067 miles |

| Public conveyance | 3,216 miles |

| —— | |

| Total | 9,264 miles |

Surely a long trip in one state! This has been over an area 625 miles long in extreme length, and has been nearly all in the coast ranges. Probably no man living has so extensive a knowledge of the coast ranges of this state from personal observation as I have, but I have seen very little of the grand features of the Sierra. When our report comes out I anticipate that it will attract much attention in the scientific world, probably more than it will here.

I do not think the Survey will be continued another year, although we have the work only fairly begun. Various influences are at work that will give us much trouble to keep it alive. The two principal ones are that the work is in advance of the intelligence of the state, and is, therefore, not appreciated; and, a more potent one, that several prominent politicians have hoped to use the Survey for personal, private speculations in mining matters and have failed—they will oppose us. You have no idea of the political corruption here. If the Survey “goes in” this winter, I shall endeavor to get into a position here, at least for a time.

San Francisco.

December 27.

When I wrote my last letter and sent it by the last steamer, I thought that I closed my journal for the year, but since that time new and stirring events have occurred, worthy of being recorded in my chronicles.

The first, and most important, turned up soon. I have told you of our troubles in money matters. Well, $5,000 had been promised surely in December, then the twentieth fixed. All looked forward to this day—all were in debt, all had much salary due. My salary at the end of this month if not paid, would be about $1,760 behind—a snug little sum. In the meantime, as I had got no money for a long time, I had run about $500 in debt, on part of which I had to pay 21/2 per cent per month interest. The twentieth came—but instead of the money, a letter came from the scoundrel who is comptroller, telling us that we would not be paid until May! To say that we were indignant would be expressing it mildly. Indignation is not a strong enough word, but the matter can’t be helped.

This so deranges our affairs that I have changed my plans, and may be home in March or April, if I can raise the money. I set out immediately to see about a professorship in a college here. I find that I can, in all probability, get it, so will probably go home in the spring, work up my report, and return here in June or July—this is my present plan—and then keep in the service of the state if the Survey is continued and the state pursues a different policy. Otherwise, I shall accept a professorship. The latter will not pay so well, nor be so conformable to my tastes, but it is well to be on the lookout for emergencies.

The next thing is something else!

Monday, December 22, was a cold, raw, blustery day, with some wind and rain. I am well acquainted with a Mr. Putnam, an officer in the California Steam Navigation Company, a monopoly that controls all the central and coast steamer business. I often visit in his family—he has four lovely little girls, the eldest thirteen or fourteen years old.3 The company was to launch a new and fine steamer, the Yosemite, which lay upon the stocks at the Potrero, about five miles distant. A little steamer, the Paul Pry, was to go down to see the launching and carry invited guests. I was invited, and managed to have invitations extended to Averill, Gabb, and Hoffmann. We left at half-past ten, with about 150 or 200 guests.

Owing to the bad day, only half a dozen or so were ladies; the rest were gentlemen, numbering some of the most noted men of the city, public officers, etc.4 It was said that Montgomery Street was represented by the owners of over five millions of capital in that little party. Katie Putnam was placed in my charge, but her father came on board just as we sailed. The launching was a beautiful one, the first sight of the kind I had ever seen—it was successful, and all were delighted. The Paul Pry was headed for home again, and we sat down to a most sumptuous lunch, where cold turkey and champagne suffered tremendously.

In the harbor is a little island, called Alcatraz, a mere rock of perhaps three or four acres, rising in cliffs from the sea about 150 feet, crowned with a fort, the defense of the interior of the harbor and a most picturesque object. To increase the pleasure of the trip and allow longer time for the lunch, we steamed around this island, keeping a short distance off. Lunch was finished. The wind blew a stiff breeze and whitecaps rolled. I was on the after part of the boat. Suddenly there came a crash that startled everyone. “What is that?” “What is that?” Everyone stared, but the suspense was short. We had run on a sunken rock, and stove a tremendous hole in the steamer, through which the water rushed into the hold, and she began to sink astern. Now came such a scene of excitement as I never saw before. The steamer rapidly settled—if she slid off from the rock, she would sink in less than five minutes; if she stuck on, she might break in two in less time.

One of the lifeboats was immediately lowered and I went below and got Katie in the boat, into which several other ladies were placed. I then stood back. The next lifeboat was run alongside and the two remaining ladies were placed in that. The excitement began to be intense. The boat had its quota of passengers instanter, when one excited individual, a prominent official, in his excitement and anxiety for his safety, jumped into the boat, fell overboard, and in getting in again upset the boat.5

Now came the most intense excitement, the boatload of passengers struggled in the water, several others jumped in, excited men were rushing frantically about, and, to increase the confusion, the boat took fire in the hold, and to extinguish it the steam from the boiler was blown there, which filled the whole vessel. Most luckily the lifeboat was righted and all were rescued from the water, the boat was bailed out, the wet passengers were put in, and she pushed off.

We were scarce three hundred yards from the end of Alcatraz Island. Soldiers were seen running around and soon boats put out. A whaleship also, seeing our signals of distress flying, sent off a whaleboat for our relief. The steamer, meanwhile, settled astern, and her bow raised high out of the water, but she stuck together. Boats soon arrived, and in about an hour all were safely landed at the fort.

I really felt ashamed for my sex, for manhood, when I saw what arrant cowards some of the men were. About two-thirds were as cool as if nothing had happened, but some of the remainder showed a cowardice most disgraceful.

After I saw Katie safe in the first boat,6 and saw the second boat rescued, I went back on the upper deck, away from the excited men who clustered around the gunwale to rush into the boasts that should first arrive. If the boat sank, I did not want to be among such men. All of our party showed that they had seen Californian camp life; not one showed the least trepidation or concern—coolness would hardly express it, and yet that was it. While coats, hats, umbrellas, furniture, etc., were seen floating away from the wreck, none of us could tell of such losses. We laughed at Averill because he carried away a glass tumbler in his pocket as a memento of the occasion, and the rest in turn laughed at me because I came ashore with not only my old cotton umbrella, but also Katie’s that she had left.

As we left in the last boats (in fact, I was in the last but one), I had a good chance to see the whole affair. I was all prepared to swim if the boat went down. Many of the scenes were ludicrous in the extreme. Men who were the loudest to talk, here were pale as death and rushed for the earliest boats, even before the women were in. I sat on the upper deck and watched two excited men. One took out papers from his inside coat pocket, pulled off his coat and threw it overboard—off with his boots, etc. I afterward saw him in the boat without coat or hat. Another stripped to his drawers; others kept near someone who they thought could swim!

Hoffmann, Gabb, Putnam, and Averill had gone before I left. All excitement had died down—the cowards had left in the earlier boats. It was raining furiously and the water had partly filled the cabin and was sweeping on the deck with every wave. As I went below to get into the boat, I met the reporter of the Daily Bulletin, with whom I was well acquainted.7 He stopped me to get “the exact time” and other “items.” He was scribbling away as if there was no danger of the boat either going to pieces or sinking. He came in the next, and last, boat. A steam tug, however, soon came and got off a part of the furniture.

We were some two hours on the island; it stopped raining and we had a good chance to see the fortress. The officers treated us with every attention, and we were finally brought back to the city on a steam tug. Thus ended our mild “shipwreck.”

The steamer did not go to pieces as was expected—we last saw her with her bow high in air, her after cabins entirely under water, which came above her upper deck. She was got off the next day, and hopes are entertained that she may be repaired for $20,000 or more.

But excitements were not to cease. The next morning, December 23, at half-past five, the city was visited by the severest earthquake that has been felt for some seven years. To say that houses rocked like ships in a tempest would be putting it on too thick, but they did pitch about in an uncomfortable way. The sensation is so peculiar that I cannot describe it. Three shocks followed in quick succession, the whole lasting not over six or eight seconds. The first awakened me, and with it came a slight nausea. The bed seemed lifted, then it shook, and the house rocked, not as if jarred by the wind but as if heaved on some mighty wave, which caused everything to tremble as it was being heaved. A few feminine screams were heard in other parts of the house. I got up and noted the time, but it was an hour before I could sleep again. No serious damage was done—we hear of walls cracked, plastering shaken down, clocks stopped in many houses, furniture thrown down, and such things—nothing more. These mysterious quakings and throes of Mother Earth affected me as no other phenomenon of nature ever did.

Christmas Eve I went to midnight Mass in one of the Catholic churches. Christmas was a most lovely day, the city seemed alive, all seemed happy. I took dinner with Mr. Putnam,8 and in the evening attended a large concert with Mrs. Ashburner. Yesterday I dined with Professor Whitney, along with Baron Richthofen,9 a distinguished young Austrian nobleman and scientific man, now in this city. He has lately been in the East Indies, China, Japan, etc., and came from there here. We all went to T. Starr King’s in the evening and had a most pleasant time.

Sunday, December 28.

It is one of the most lovely days of the season. The sky is bright, and the air of matchless purity, the mountains fifty or sixty miles distant seem as clear as if but half a dozen miles away. All the city is in excitement over the capture of the California steamer, Ariel, by the British pirate, Alabama, or “290.”

I was at church this morning, an Episcopal church, all decorated with evergreens, and this afternoon it seems as if all the city was in the street.

The customs of Europe and of the East are transplanted here—churches are decked with evergreens, Christmas trees are the fashion—yet to me, as a botanist, it looks exotic. With us at home, and in Europe, the term “evergreen” seems almost synonymous with “cone-bearing” trees, and so the term is used here. Churches are decked with redwood, which has foliage very like our hemlock—it is called evergreen, but it is hard for the people to remember that nearly all Californian trees are evergreen. While at Christmas time at home the oaks and other trees stretch leafless branches to the wintry winds, here the oaks of the hills are as green as they were in August—the laurel, the madroņo, the manzanita, the toyon, are rich in their dense green foliage; roses bloom abundantly in the gardens, the yards are gaudy with geraniums, callas, asters, violets, and other flowers; and there is no snow visible, even on the distant mountains. Christmas here, to me represents a date, a festival, but not a season. It is not the Christmas of my childhood, not the Christmas of Santa Claus with “his tiny reindeer,” the Christmas around which clings some of the richest poetry and prose of the English language. I cannot divest my mind and memory of the association of this season with snowy landscapes, and tinkling sleigh bells, and leafless forests, and more than all, the bright and cheerful winter fireside, the warmth within contrasting with the cold without. So do not wonder if at such times I find a feeling of sadness akin to homesickness creeping over me, that my fireside seems more desolate than ever, and my path in life a lonelier one.

NOTES

1. California nutmeg, designated by Jepson as Torreya californica Torrey (Silva of California [1910], p. 167), but by Sudworth as Tumion californicum (Torrey) Greene (Forest Trees of the Pacific Slope [1908], p. 191), is not related in any way to the nutmeg of commerce. California laurel (Umbellularia californica Nuttall) is found at its greatest and most profuse development near Tomales Bay.

2. Ashburner continued for a number of years to be a consultant for the Bank of California.

3. Miss Marion O. Hooker, of Santa Barbara, writes, September, 1929: “The family of Samuel Osgood Putnam has lived in or about San Francisco ever since 1853 when Mrs. Putnam and her three-year-old daughter joined Mr. Putnam there. My mother’s first experience of a wreck was at this age on the Tennessee, in process of arriving at her new home. Of the six children, three are living: my mother [Mrs. Katharine Hooker]; her sister (Mary), Mrs. Morgan Shepard, in New York; and Edward W. Putnam, in San Francisco. (Miss) Caroline Rankin Putnam, (Miss) Elizabeth Whitney Putnam, and Osgood Putnam have died.”

4. “There were the Collector of the Port, Naval Agent, Surveyor of the Port, Postmaster, Captains Baby, Seeley, Barclay, Pease, one of the newly elected Pilot Commissioners, and other gentlemen familiar with salt water, besides Captain Winder and other officers from Alcatraz, leading merchants, lawyers, etc., and the ubiquitous representatives of the press—all anticipating a delightful excursion, and each evincing a disposition to cultivate those social amenities which are so indispensably necessary to real enjoyment on festive occasions of this character” (Daily Alta California [San Francisco, Tuesday, December 23, 1862]).

5. “Just as the boat was pushing off, the newly elected Pilot Commissioner aforesaid, at once perceived that there was no person aboard sufficiently skilled to assume the management of the craft. He sprang to the rescue, and in doing so capsized the boat, pitching all hands, and heads, and bodies into the foaming briny deep” (ibid)

6. Mrs. Katharine Hooker writes, September, 1929: “My father insisted on dropping me down into the first boat, among the agitated ladies, much against my will as I wanted to remain with him. Then and there a singular fact came to light—I was tucked in by the side of Mrs. Chenery with whom I had been wrecked once before, at the age of three. When the steamer Tennessee, headed for San Francisco from the Isthmus of Panama (1853), ran on the rocks just north of the opening of San Francisco Bay, having missed its bearings in the fog.”

7. The San Francisco Bulletin (December 23, 1862) contains a spirited account of the wreck, not quite so facetious as that in the Alta.

8. Mrs. Hooker writes: “Professor Brewer. . . was a great friend of our family and a familiar visitor at our house. We were all very fond of him. Besides the long talks with my father, he was devoted to the younger children and I often picture him with a little girl on each knee, while they sang, and he trotted them with a vigor that never failed.”

9. Baron Friedrich von Richthofen worked from time to time with the California State Geological Survey and was a lifelong friend and correspondent of Whitney’s (Brewster, Life and Letters of Josiah Dwight Whitney [1909], p. 240).

| Next: Book 4 • Contents • Previous: Chapter 6 |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/3-7.html