Map of Rail & Stage Route to Big Tree Groves and Yosemite

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Wonders > 1872 >

Map of Rail & Stage Route to Big Tree Groves and Yosemite |

Those who visited the famous Valley in 1869, 1870, and even 1871, will find that much of the fatigue, dust, vexatious delays, and the cuticular abrasions incidental to prolonged saddle excursions, may be avoided by the improved facilities for travel in 1872. In fact, it may almost be asserted that the only horseback riding necessary now, is the descent of the mountains directly into the Valley, a distance of only three miles, and occupying not more than two hours of time. Indeed the speed and comparative comfort of the trip now rob it, in my opinion, of much of the charm and delightful feeling of freedom which attach to equestrian exercise among magnificent mountain scenery, even though the air-passages be choked with dust, and the bones ache from riding. On your horse you are free to stop and admire when you please; in the stage you have much dust and as much fatigue, though of a different kind, crowded into fewer hours, with the additional discomforts of cramped position, inability to see, and disagreeable joltings, against which you cannot guard.

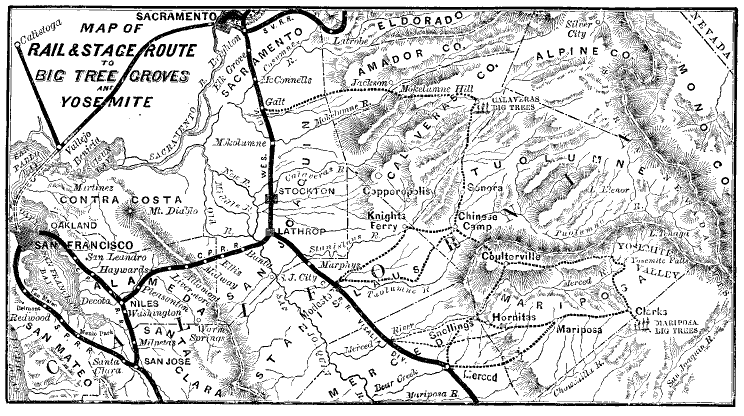

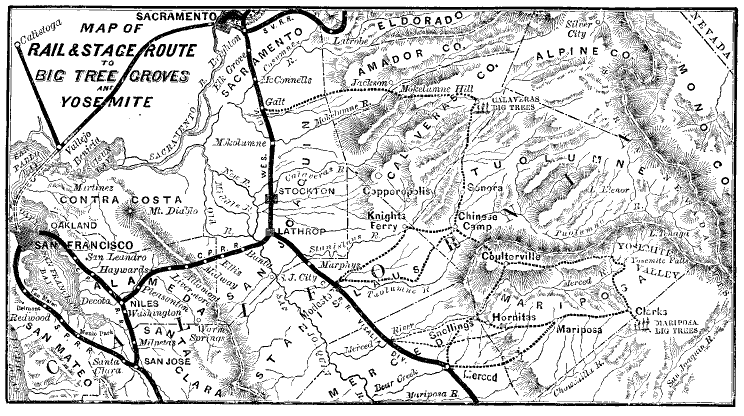

By consulting the maps, the reader will be able to trace the different routes to the Valley, and to locate in advance the most remarkable cliffs and waterfalls described in the previous pages.

It is estimated that in 1869, about 1,100 Visitors entered the Valley; this number, in 1870, was increased to 1,700, and in 1871 to 2,300; in 1872, it is safe to predict that at least 3,000 persons will behold its beauties. Judging from the expressed intentions one hears around, many hundred persons from this vicinity will substitute this for their summer trip to Europe and the fashionable watering-places.

It is understood that the “American Association for the Advancement of Science” has this year been invited to meet in San Francisco. Californian generosity and hospitality are proverbial; and the treasure which she lavished on the “Sanitary Commission,” will not be stinted in furnishing facilities for the “Scientific Brotherhood,” who are looking with longing eyes to the Pacific shore. Her fertile plains, her magnificent forests, her inexhaustible old fields, her immense orchards and vineyards, her salubrious climate, make her the envy of the more sterile Eastern States. No doubt she will extend such a welcome, that the scientists from every state will find it in their power to cross the continent by the Pacific Railroad. This will probably lead to the Yosemite many a geologist, to speculate upon the mighty agencies of convulsions, ice, and water, which have combined in the formation of the great Valley; many a botanist, to revel in the gorgeous floral richness and in the unparalleled forest growth of the mountain meadows and gorges; many a true lover of nature, to appreciate and extol the sublimity and beauty of the Sierra Nevada, with its cliffs and falls. So may it be!

Even Californians do not seem to be aware what a magnificent trust the United States have committed to their care. It is understood that parties who think they have a claim to portions of the Valley, from squatting upon, and, in their idea, improving the land therein (though having none, as the region had not been surveyed), have been busy the past winter in endeavors to have their titles legalized. If these persons have made what they regard as improvements, let them be paid amply therefor; build a golden bridge for them to pass over, and let them carry at once and forever by this pathway, cheap at any price, all supposed claims to this part of the national domain. True, it has no gold, nor fertile land, nor available forests, to tempt the cupidity of individuals, or in any way to increase pecuniarily the value of the State; but it has that which no money can purchase—the sublime and beautiful in nature—what will render the State more famous than her mines and her grains, and will do more than her institutions of learning, noble as they are, to elevate and cultivate her people. Every lover of his country, and of her grand scenery, is interested to prevent the acknowledgment of all claims, under whatever pretence advocated, of private individuals, or of corporate bodies, to any part of the Yosemite Valley and its surroundings, as fixed by the Act of Congress alluded to in the preceding pages.

Let the “American Association” speak the united demand of the sciences they represent, at the meeting of 1872, and put a stop forever to the vandalism which has assumed such threatening proportions. Let the State assume the responsibility of the roads, the new trails, the bridges; let her forbid the erection of any more shingle houses for trading, or drinking purposes, and level with the earth many now existing, the continued building of which will make the Valley look like the cloth-covered shanty villages which appear and disappear as a new railroad progresses on the plains—a sort of house-caucer, which follows the avenues of travel, carrying in its course gambling, whiskey, and riot, and remediable only by the strangulating surgery of “Vigilance Committees.”

Let the cutting down of trees be stopped by more stringent measures, the present law not being strictly enforced. Let no man fence up meadows belonging to the State, and charge travellers pasturage for their horses on the public domain. The beautiful wild flowers and thickets, classed by the soulless improvers as useless chapparal, are trampled by cattle and destroyed by the plough. But fortunately, in the language of one who knows whereof he speaks, and is filled to overflowing with the beauty of Californian nature, “By far the greater portion of Yosemite is unimprovable; her trees and her flowers will melt like the snow, but her domes and her falls are everlasting.”

Let not the Golden State permit her own and her sister populations to regard the Valley of the “Great Grisly Bear” (Yosemite) rather as the valley of the “Golden Fleece.”

Every traveller, coming from the East, should stop at Stockton, California, and make that city; the point from which to start on the tour of the Calaveras Grove, Yosemite Valley, and the Mariposa Grove, all of which, if times permits, should be included in the trip. Presuming that the traveller wishes to avoid, as much as possible, horseback riding, and avail himself of railways and stages where practicable, Stockton is the proper base of departure. Various routes are open to the traveller, and very eloquent and pertinacious advocates will soon beset him, assuring him positively that speed, comfort, safety, and moderate charges can be secured only on the route for which he is employed as runner; as all are made out equally advisable, each in turn, the traveller will naturally and properly decline to believe all that is told him by the rival advocates. All the routes have their advantages, and all their disadvantages, and, after all, there is not much to choose; you will be surely disappointed in some things, while others will surpass your expectations. Taking things easy, and making the best of what offers, and not expecting, in this new and rough country, the punctuality and the little comforts he has become familiar with in the palace cars, are what make the philosophic traveller enjoy himself in spite of minor inconveniences, while the male fuss-bug and the female fidget are disgusted with everything, and pronounce the Yosemite trip a humbug and a bore.

Heavy trunks should be left at Stockton, as you will surely return thither, whether you approach the Valley from the east or the west; they will be unnecessary and a nuisance, difficult to carry by stage and impossible by horses, and, if carried from Stockton and left, necessitating return by the same route, which is not advisable if you wish to see the most you can in a short time. A valise that can be carried by hand, or easily packed on a horse, is enough for a fortnight’s trip, and few make one more than ten days’ long; for gentlemen, are desirable a broad-rimmed light hat, strong boots, serviceable but not too nice clothes, with flannel shirts; for ladies, flounces, trains, high-heeled boots, and fashionable hats are quite out of character; the clothing should be about what would be worn here in the latter part of spring; the heat may be ninety degrees Fah. at noon, in the Valley, while the nights and mornings are cool; umbrellas are useless impediments.

In my judgment, the best route to follow, if you are not in a great hurry, and wish to visit the Calaveras grove of trees, is this: taking the railroad at Stockton you go to Milton or Copperopolis, a distance of twenty-eight or thirty miles; there you take stage for Murphy’s, a distance of thirty-seven miles; seventeen miles farther by stage will bring you to the Calaveras grove of big trees, occupying ten hours. Remaining one day in the grove, previously described, you start in the morning for Murphy’s again; dine at Sonora, and take supper at Chinese Camp, going on to Garrote, which you reach at nine p.m., there passing the night; on this day you have ridden about sixty-seven miles by stage, the distance from Murphy’s to Garrote being fifty miles; the roads are better than on the old Mariposa route, the hotels are comfortable, and the fare good. Next day, before light, you start again, reaching, at noon, Crane’s Flat, a distance of thirty miles; about half-past one you leave again, and by the middle of the afternoon arrive at “Prospect Rock,” the end of the stage route; here you get the first glimpse of the Valley, though not so good as the one from “Inspiration Point,” on the Mariposa route. You then mount your horse, descend the mountain about three miles, and reach the hotels in the Valley about eight p.m.—having ridden seventeen miles from Crane’s Flat without any great fatigue.

Then making the tour of the Valley by stage, and on horseback, you visit the various points of interest, noted on the accompanying map, and previously described, spending not less than three days. If you ascend the high Sierra, toward the upper Yosemite fall, or go to Cathedral Peak, which is strongly advised to all good climbers, for the purpose of seeing the polishing of the rocks—in the vicinity of the beautiful lake Tenaya, especially—the work of the ancient glacier which once ploughed its way, miles in length and width, and thousands of feet in thickness, along the top of the Sierra, filling up the Yosemite Valley, and extending twenty miles or more along the plain of the Merced River—you must stay half, or, better still, a whole week longer. Nowhere can be seen better evidence of the immense power of ice in shaping the hardest rocks, than in the easily accessible heights on the north side of the Valley.

It will be well to return to Stockton by the Mariposa trail, as by that you visit Sentinel Dome, the Mariposa trees, and pass through the interesting gold diggings of Mariposa and Bear Creek. It is longer and more fatiguing, and with more horseback riding than the Coulterville route. These routes can be well understood from the accompanying excellent map of the region, kindly furnished by F. Knowland, Esq., General Agent of the Union and Central Pacific Railroads. In Summer, tourists will be able to descend from Sentinel Dome as well as by the Mariposa trail on the south side, and by Indian Cañon, as well as the Coulterville route, on the north side; but it is best for most travellers, especially for ladies, to make the descent by the oldest and best trails; by all the routes you can go by stage almost to the edge of the Valley.

Going out, then, by the Mariposa trail, you ride by stage (or on horseback, if you prefer it) to the western end of the Valley, along, but not crossing, the placid Merced River, passing near the Bridal Veil fall.

Mounting your horse, you ascend a steep and winding path, often casting a fond, lingering look behind at the beautiful Valley, till it is lost from sight; you arrive in about an hour at “Inspiration Point,” from which, coming from the other direction, you obtain the first glimpse of Yosemite, and probably the grandest view in the country, if not in the world. Lingering here as long as you can, you branch off to Sentinel Dome and Glacier Point, from which the view of the distant Sierra, embracing the Obelisk, Mount Lyell, and Mount Dana groups of mountains, is indeed magnificent. Thence to Westfall’s meadow, and to Clark and Moore’s, 25 miles from the Valley, where a genuine New England welcome awaits you.

Distant from their hotel about five miles is the Mariposa grove of big trees, where the “Grisly Giant” stands erect, about 300 feet high and 90 feet in circumference at the base—with scores of smaller giants, male and female, married and single, as indicated by their names.

Returning to the hotel you take stage for Mariposa over a very good road, with an oasis in the desert called “White and Hatch’s,” where a second New England welcome and home-like table will refresh both mind and body. From Mariposa you go by stage through the decayed mining region of that name, where a few Chinese still search for gold successfully in the deserted diggings. The end of your dusty ride soon ends, as you strike the Visalia division of the Central Pacific Railroad at Modesto, 20 miles from Lathrop on the main railroad; thence to Stockton 10 miles, after a stage ride of about 90 miles.

By this route you pass through Calaveras, Tuolumne, Mariposa, Merced, and Stanislaus counties, and get an excellent idea of the Sierra and the foot-hills. If the Calaveras grove be omitted, the tourist should by all means enter the Valley by the Mariposa route, for the sake of Sentinel Dome and Inspiration Point, and go out by the Coulterville trail; then, on reaching Chinese Camp, should the appetite grow by what it feeds on, and time allow, it is easy to go up to the Calaveras grove—or the traveller may return by Knight’s Ferry to Modesto, or whatever may then be the terminus of the Visalia branch to Stockton. Should the railroad be finished to Bear Creek or Merced, the stage route by way of Mariposa will be shortened some 30 miles, and will be and additional inducement to enter the Valley by this route, returning by Modesto.

Time from Stockton back again, including three days in the Valley, the Calaveras circuit, Sentinel Dome, and the Mariposa grove—ten to twelve days. Fare from Boston to San Francisco, $142—time to Stockton, 7 days, for which $5 to $6 a day should be allowed for sleeping-cars and meals; the Yosemite trip will cost from $125 to $150, according to the manner of conveyance, and the number of the party: the total necessary expense per individual, with a few days in San Francisco, is not more than $600. Beyond Utah, greenbacks should be exchanged for gold and silver.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/wonders_of_the_yosemite_valley/13.html