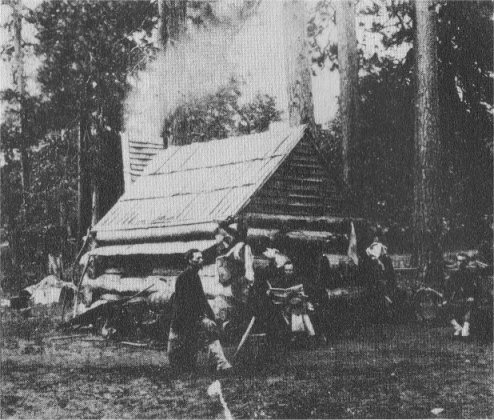

Photographed in 1861

FIRST CABIN BUILT IN YOSEMITE

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Indians & Other Sketches > James C. Lamon >

Next: James Hutchings • Contents • Previous: Indians

JAMES C. LAMON

Photographed in 1861 FIRST CABIN BUILT IN YOSEMITE |

granite

shaft in Yosemite Cemetery reads:

“James C. Lamon. Died May 22nd, 1875 aged 58

years.” Little is known of Mr. Lamon, yet that little

reveals a distinct personality, a rare character,

and a life rich in simple kindliness. He was a recluse

who lived his life in solitude, and who was often called “Hermit of

Yosemite.” Those who knew him, speak of him as retiring and

unostentatious in manner—a man to be trusted.

granite

shaft in Yosemite Cemetery reads:

“James C. Lamon. Died May 22nd, 1875 aged 58

years.” Little is known of Mr. Lamon, yet that little

reveals a distinct personality, a rare character,

and a life rich in simple kindliness. He was a recluse

who lived his life in solitude, and who was often called “Hermit of

Yosemite.” Those who knew him, speak of him as retiring and

unostentatious in manner—a man to be trusted.

His nephew has given us something of the background of this refined, sensitive man with whom it is difficult to associate rough mining days of early Mariposa. James Chenowith Lamon, fifth in a family of fourteen children, was born in West Virginia in 1817. In 1836 the family moved to Illinois and settled on a farm. James had but a common school course. A brother, Robert Bruce Lamon, served as a member of the California State Legislature. In 1839 James C. Lamon went to Texas—then a Republic—and entered the service when war broke out with Mexico. In 1850 he went to California to join his brother, Robert Bruce Lamon. In 1852 the Lamon brothers and David Clark became partners in a lumber mill in Mariposa County. In 1858, while Robert Bruce Lamon was on a visit in the East, the lumber mill burned and unfortunately there was no insurance. Robert did not return and James decided to go to Yosemite as he knew something of the Valley through his brother Robert, who led the first sight-seeing party into Yosemite Valley in 1854.* [*J. A. Lamon, nephew of James C. Lamon, in June, 1932, writes: “My father, Robert Bruce Lamon, knew most positively that his party was the first outside the Indian fighters. He learned of the Valley from Captain Boling and Mr. Savage and persuaded five of his friends to join him in a trip of exploration and entered the Valley in 1854.” Concerning the pronunciation of their name, he states : “Our name is pronounced as though it was spelled Lemon—the “a” having the sound of “e” as in “any,” “many,” etc.] This party, in honor of its leader, Robert Bruce Lamon, named the falls above Vernal Falls, “Lamon Falls” and placed a sign there with this name. No doubt it was lost in the snow and storms of the winters but the present name, Nevada Falls, robs history of this interesting data.

In June, 1859, James Chenowith Lamon arrived in Yosemite Valley, located and preempted 160 acres, in three detached portions, in the upper end of the Valley* [*In 1898 Robert Bruce Lamon, after a lapse of forty years, revisited Yosemite. Of his brother’s orchard he says : “Some of the trees I find still standing and also part of the post-and-rail fence he enclosed them with.”] (Report of Commission to Governor H. H. Haight, 1869), and remained there the rest of his life. He built the first log cabin in Yosemite, locating on the south side of the Valley. The Sacramento Record-Union, May 24, 1875, says: “The cabin is of rough logs, dirt floor and no windows, and contains a granite fire-place, a cot, table, cupboard, bearskins etc.” Mr. Lamon cultivated a garden of vegetables and small fruits and planted two large orchards.

A letter from Galen Clark to Robert Bruce Lamon dated June 6, 1898, reads in part as follows: “Your brother James commenced improvements on his place in Yosemite in 1859 but did not spend a winter there until 1861-1862 and 1862-1863 which winters he spent there alone. In the winter of 1861-1862 there was a rumor that a man had been killed by the Indians on the trail to Yosemite. I got Gus Hite to go with me to Yosemite to see if your brother was all right. We found Jim well and exceedingly glad to see us and to get some of the later news.”

There is quality and capacity in a man who, shut off from all human contact, is able to live in the solitude of his lonely hut through winter storm and snow. In 1864 J. M. Hutchings and his family began wintering in the Valley. His daughter, Gertrude Hutchings Mills, in a letter in 1932 writes: “I can remember Mr. Lamon very well with longish hair beneath his hat brim, and trousers tucked in his cow-hide boots, driving his team of large, red oxen. He helped my father by hauling logs to the little mill near the foot of Yosemite Falls. He was a quiet but not an austere man, much liked and re[s]pected.” Mr. Lamon’s door was ever open with true and generous hospitality. John Muir writes: “He was a fine, erect, whole-souled man, between six and seven feet high, with a broad open face, bland and guileles as his pet oxen . . . many there be, myself among the number, who can testify to his simple unostentatious kindness that found expression in a thousand small deeds.”

James Chenowith Lamon was one of God’s born gentlemen. He was a neighbor in the truest sense to all who needed him. If the ties of home and family were not for him and the depths of his heart remained forever unexpressed, there yet radiated out of his simple life of solitude an atmosphere of mellowed richness and quietude that made him a figure apart from the ordinary.

In September, 1930 the writer visited Henry Hedges, of Mariposa, the first bus driver into Yosemite. He spoke of Mr. Lamon’s fine garden of vegetables and small fruits irrigated by water from the Royal Arches; his marvelous strawberries, some as large as hen’s eggs; his two large orchards of choice fruits. No tourist omitted a visit to the cabin of Yosemite’s first settler. Mr. Hedges often helped him pack away his apples for winter, placing alternate layers of grass and apples in a hole dug below the freezing point where the fruit kept perfectly. Mr. Hedges added: “I wish you could have seen Lamon’s fine, big oxen —Dave and Brownie— both of ’em red. They seemed to belong to the Valley and everybody liked ’em. They did all the ploughing and cultivating in the orchards and no end of hauling logs.”

After Mr. Lamon’s death in 1875 Mr. Harris leased the place. Replying to a letter in September, 1930, Mrs. Esther Harris Nathan said: “Among the apples in the Lamon orchard were Winesaps, Gravenstein, Rhode Island Greening, Russet, Fall Pippin, Baldwin, Water Core, Red June, and Maiden Blush or Lady Gregory. The plums were Green Gages.” Mr. Lamon’s gardens and orchard were of interest and pleasure to the tourist. In the book, To San Francisco and Back, by a London Parson, the author says (pp, 97-98): “There is but little cultivation in the Valley. One enterprising man had planted a spot with vegetables, and pear, apple, plum, and peach trees. Where he found a market for their produce it was hard to say, unless, as is possible, he relied upon selling to visitors what he could not eat. His orchard had no fence, and he himself was not to be found when we paid it a visit. Outside a little hut, however, close by, was a paper with the following notice: ‘Anyone helping himself to a mess of fruit from my patch will please put 2 Bits through a hole in my door, and oblige J. C. Lamon.’ We helped ourselves liberally to peaches and apples, and complied with the request, adding a little more for the pocket fulls we took away.”

Mr. Lamon built a second and more commodious cabin on the north side of the Valley, near the Royal Arches, where he obtained the maximum of sunlight and warmth. This was his home; here he lived a busy and contented life, and here he died.

In 1864, through an Act of Congress, Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees became a state park. The Act was approved by the California Legislature in 1866 and the Commissioners advised Mr. Lamon that henceforth there could be no privately owned land in the park and that he must lease his premises from the Board of Commissioners. That he should lease land that had been his by preemption for seven years, seemed for a time impossible to Mr. Lamon. After trying for five years to substantiate his claim he presented to the State Legislature the following memorial: (Commissioners’ Report, 1870. Being a Message of the Commissioners of Governor H. H. Haight transmitting the report of the Yosemite Commissioners and the Memorial of J. C. Lamon.)

“Yosemite Valley, December 4th, 1869.

“To the Honorable Senate and Assembly of California:

“Your memorialist would respectfully represent that he is a citizen of the United States of America, of the State of California, and of the County of Mariposa. And your memorialist would further represent, that in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-nine, he settled in and became a resident in the Yosemite Valley, in the aforesaid County of Mariposa, and that at that time he purchased claim there of certain persons who had taken them up under what is known as the ‘Settlers Act’ of the State of California.

“And your memorialist would further represent, that he went to work making improvements in good faith, believing that he would eventually be allowed a pre-emption or homestead right to the land upon which his improvements were located, by the United States Government; and that he has from year to year, and constantly, up to the present time, labored industriously making improvements, enduring great privations and hardships for many years, being fifty miles up in Sierra Nevada Mountains from the nearest town or Post-office.

“And your memorialist would further represent, that in the year provements consist of houses to live in and a barn, of fences, and a very fine garden; of large patches of various kinds of berries, such as strawberries, raspberries, blackberries and others. Also, of two large and very fine orchards of fruit trees, now beginning to bear abundantly, being of the very choicest selection of grafted fruit, consisting of apples, pears, peaches, plums, nectarines, almonds, etc. , over one thousand trees altogether; all of which have been transplanted and cultivated with the greatest care and labor, in thoroughly and deeply preparing the ground, and constant cultivation.

“And your memorialist would further represent that all these various improvements, which have cost him ten years constant hard labor, together with considerable hired labor, he believes at this time to be worth at least twelve thousand dollars.”

“And your memorialist would further represent, that in the year one thousand eight hundred and sixty-four the Yosemite Valley was, by an Act of Congress, granted and ceded to the State of California, on condition that it should be held forever inalienable as a place of public resort and recreation, and that the State of California has, by an Act of her Legislature, accepted the grant upon and in accordance with the stipulations named, and has appointed a Board of Commissioners to take charge of the Yosemite Valley, with full powers to possess it and manage all matters pertaining to the same.

“And your memorialist would further represent, that the Commissioners appointed to take charge of the Valley have brought suit of ejectment against him, to dispossess him of his various improvements, which suit is now pending against him, and still undecided.

“And your memorialist would further represent, that if said suit should be decided against him, it would deprive him of all his earthly possessions and leave him in poverty and in debt.

“And your memorialist would further represent, that if he can be paid for his various improvements, according to their full value, by the State of California, he would be willing to vacate the premises and give possession of all his improvements to the Commissioners appointed to take charge of the same.

“Therefore, your memorialist would most re[s]pectfully ask that the State of California would pay him the full value of his possessions, that he may not be utterly impoverished.

“And your memorialist would ever pray.

“J. C. Lamon

“Witness:

“Galen Clark

“Fred Leidig”

The State Legislature, in the fall of 1874, accepted the terms of the memorial and paid Mr. Lamon twelve thousand dollars. He went to Oregon to visit a sister he had not seen for thirty-five years. Her children were a great joy to him and he was loathe to leave, but the log cabin was home, and he returned to Yosemite and leased from the commission the tract he had developed into gardens and orchards. A sapling may be transplanted; a man nearing sixty is not easily uprooted.

In the spring of 1875 Mr. Lamon became ill. Mrs. J. M. Hutchings and her mother cared for him in his fatal struggle with pneumonia. He died May 22, 1875. His executor was his friend, Galen Clark. Gertrude Hutchings Mills attended the funeral. She says: “I was lifted up to see Mr. Lamon ‘asleep’ in his pine box and I struggled to get away before I should awaken him.”

The Sacramento Record-Union, May 24, 1875, says: “It was a fitting day, time, and place for his burial—the Sabbath. . . . We went up the river banks and culled a basket frill of sweet, white azaleas and made a wreath and a cross to place on the coffin. It was an imposing scene—a procession of over a hundred people, gathered from all lands, and many Indians, most of them on horseback, winding up to the new made grave under the oak by the shining wall. Two clergymen read the beautiful service as he was laid to rest.”

The Mariposa County Gazette of Saturday, May 29, 1875 recorded: “Another pioneer gone. John [James] C. Lamon. One of the oldest settlers in this county, and long a resident of Yosemite Valley, died at that place on Saturday last. He was eccentric in his habits, but the very soul of honesty and good feeling. As an instance of this, some years since he became involved, and liquidated his debts at the rate of fifty cents on the dollar. Afterward he recuperated, and paid off every cent of his indebtedness. . . .” These few lines are a rare tribute in the evaluation of eternal qualities. The quiet, retiring life of James C. Lamon radiated righteousness and kindliness throughout its days. The essence of his simple life and kindly spirit will eternally live in the Yosemite Valley.

The following appeared in the Youths Companion in 1875:

One June day last summer our little party dismounted from their horses at the toll-house near Register Rock. As three forlorn-looking females sauntered into the room, there rose from his seat by the fire a tall, straight, loose-jointed man, with grizzled hair and beard, a sparkling, pleasant eye, and a friendly face every line of which bespoke us welcome.

“This is Mr. Lamon, the pioneer of Yosemite,” said our guide, and we all shook hands. . . .

He was a wayfarer like ourselves, and had stopped on his way to “Snow’s,” so we pressed him to wait until our party had also rested, and then go on with us.

As we sat around the roaring fire (Register Rock is a cool, damp place even in the middle of June) we heard much Yosemite lore told with the pleasantest voice and in the quaintest way in the world. He first settled there in 1859, when he built the old log cabin which still stands like a monument of his lonely life, although no longer occupied as a residence.

At that time visitors to the Valley were few, and there was no one to dispute him when he staked out his claim, planted his orchard, and cultivated his little garden. For five [two] winters he lived alone, never seeing a human face other than those of the Indians. . . who are the most unabashed, unblushing thieves in the world, and as beggars have no rivals, while treachery and murder sits as lightly upon their consciences as down upon glass. Mr. Lamon had many a story to tell. . . . One day as he was returning from a day’s hunt, shot-gun in hand and fat venison on his shoulder, he met a stalwart red man and his squaw, the latter staggering along with a heavy basket. The snow lay thick upon the ground, and all his winter’s stock of flour had been left in his unguarded castle, so it behooved the pioneer to be somewhat suspicious, egress from the Valley being impossible save upon snow-shoes.

The stalwart red man was about to pass him by with a gruff grunt, but Mr. Lamon stopped him and said, with a significant gesture at the huge basket.

“What squaw got?”

“Nothing,” was the red man’s unblushing reply, as he attempted to stride past.

“O yes!” said our friend, shifting his shot-gun in a way that caused the cautious red man to pause.

“What squaw got?”

“Fish,” was the response. “Me catches um.”

“Go by my house?” was the next question.

The red man indignantly denied having been near his house. . . . The pioneer asked more questions, with the design of entrapping his friend into making some damaging admission, but without effect; the red man gesticulated, and grew more and more indignant . . . while the squaw shook her head and said, “No, no.” Finally the pioneer said:

“Well, me look”

The red man would have objected, but the shot-gun held him in check, and when the cover was lifted, lo, the great basket was full to the brim with flour! The red man neither blushed nor faltered, but said, grunting:

“You no business leave door unlocked.”

“And what did you do?” we asked breathlessly.

“Oh, I gave them half of it, and took the other half home. I thought I could get along,” he said.

Another story was more tragic.

One day toward dusk, in the depth of winter, a solitary white man passed Mr. Lamon’s cabin. He had not even seen an Indian for over two months, and we can guess how cordially he greeted him, and hospitably urged him to stay over night in his humble home.

The man came in and rested for a few moments, but said he would rather push on; that he was a miner, and had taken the Valley in on his way back to Mariposa, because it was his last chance to see it. He was going “home,” “way down East,” to see his wife and children. He had made his pile he said: it wasn’t very big, but it was big enough for him. He was satisfied.

Mr. Lamon suggested Indians, he had seen a lot skulking about a day or two before, but the miner laughed, and pointed to his shot-gun, and pulled out his pistol, and asked if he had ever seen an Indian that wasn’t a coward.

The pioneer spoke of the deep snow, and the night that had already crept into the Valley, but the miner said he knew the trail well, and there was a good moon, and he had no fear, so he bade his entertainer good-by and trudged away cheerfully enough.

That night it snowed, and the next day and the next night; but the day after the sun came out and shone brightly all day. As dusk came on Mr. Lamon heard sounds like human voices and he saw five or six men coming toward his cabin. They cheered when they saw him and tears filled their eyes as they shook his hand. Some Indians having plenty of gold dust, a silver watch, a pistol, and a shot-gun, were placed in jail. One of them acknowledged they had murdered a lonely miner “who had made his pile” and was “going home.” And, said Mr. Lamon, he did go home, poor fellow. I found his body the next summer when the snow had melted off, and I dug a grave and buried him. No one ever knew his name. . . . He took us through his garden, bewailing that ripe strawberries were so few, and took us into his apple-house, sweet-scented with hay and fruit. I shall never forget his fastidious care in selecting fruit for the ladies, nor his hearty, laugh when our “Violet” modestly inquired why he did not have a “Lamon-ade” to sweeten life’s cup.

Last May he was taken sick with pneumonia and after an illness of a few days he died. They buried him appropriately at the foot of the beautiful Yosemite Falls, in that wonderful valley, whose glory, and grandeur, and loveliness, and peace had left its impress on his soul.

Next: James Hutchings • Contents • Previous: Indians

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_indians_and_other_sketches/james_lamon.html