[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Nature Notes > 47(3) > The Flower Season near and above Timberline during Summer of 1977 >

Next: Stock Use • Contents • Previous: Botanical History

Carl W. Sharsmith

[click to enlarge] |

What kinds of response will the plants near and above timberline show at the beginning of a Yosemite summer that follows immediately upon a winter of very scanty snows? Furthermore, what if that summer is an almost rainless one as well? Would there be any flowers to see? What were the effects of the winter? And how, in general, would the plant life fare as the extremely dry summer progressed?

The answers to these questions were not altogether what we expected them to be. It was the summer of 1977 when the above conditions prevailed, and I say “we” because then, almost each week, from mid-June until well into September, I was privileged to lead to these high places groups of our Park visitors, all of which were as interested in these questions as was I. I was, however, luckier than they. I alone was able to see and watch the progress of the whole floral show from start to finish.

To begin with, early in the season, damage and death showed themselves all too clearly in many sites exposed to the full force of the winter winds. Laden with ice-crystals, these winds had gnawed at and torn away the soil from beneath low dense cushions of perennials such as Buckwheats which later in the season would have been bright with flowers. Many of them, their long, tough, deep taproot almost completely exposed, had toppled over, and now clung by the few root-branches that remained in the soil. Others had been uprooted entirely. Among the willow thickets the all too numerous dead, blackened branches, showed the result of the scorching effect of the same drying winds. These results, however, were to be expected. Likewise expected was the lack of the usual abundance of flowers on the early bloomers of mid-June.

[click to enlarge] |

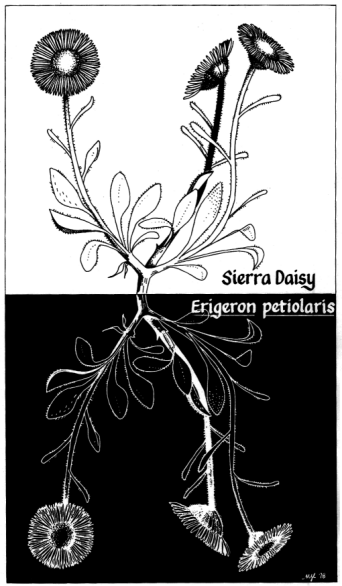

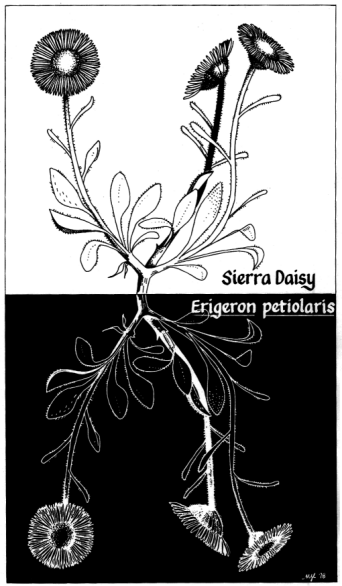

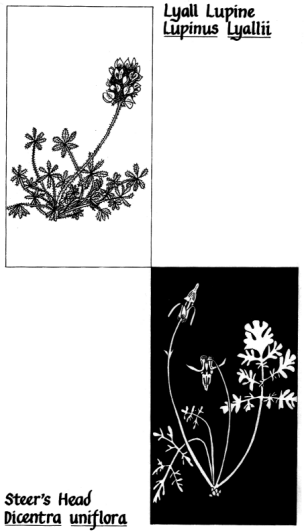

It became an altogether different story with the arrival of the warming cloudless days that now began and continued to succeed each other almost uninterruptedly week after week. This was particularly the case in certain localities on the rocky heights. The bloom was more profuse than I can remember seeing in them in the past, and I have revisited them year after year. Some of the more striking instances must be mentioned. In certain warm, wind-sheltered nooks high on a slope in dark metamorphic rocks, gardens of alpine Wall Flowers (Erysimum perenne) were each a mass of clear beautiful yellow. As we approached, even at a distance the perfume they emitted delighted our senses, and as we stood on the slope immediately below them the glorious effect of the sun shining behind them delighted another. Then, on another occasion, nearby on a slope fully exposed to the winter winds, were myriads of lavender-rayed Sierra Daisies (Erigeron petiolaris). I had never before seen so dense a stand of this species in our mountains. Again, on another day, there came a still greater surprise: a bright yellow daisy (Erigeron linearis) that has no really appropriate common name. This right on top of the fact that, a few minutes earlier I had said to the group “If a flower looks like a daisy (Erigeron) or an Aster, and has yellow rays, in Yosemite it just isn’t either of them.” Now I was a bit embarrassed, for here indeed was a yellow-rayed daisy; two flourishing colonies of it, each highly localized. We saw it nowhere else. It was very special. We were beholding a flower that is very rare in all of Yosemite. I myself had never before seen it in our Park, and had even been inclined to doubt of its existence here. Later, at another locality and occasion, were astounding hosts of the white stars of a Sand Wort (Arenaria Kingii); and again, at still another place, high above timberline, a haze of blue, easily visible from afar, covered completely the large expanse of a distant slope An extraordinarily extensive and dense stand of Lyall Lupines (Lupinus Lyallii) was the cause. If such a rich and wide display of this flower was usually appeared on this particular slope, it would have caught my eyes long ago. Likewise the Snow Willow (Salix nivalis), the tiniest of our alpine willows, that forms mats scarcely an inch high, with small, deep green, shining roundish-tipped leaves, and catkins only about six to eight millimeters long. A mile or so from our blaze of lupines, close to an altitude of 12,000 feet, yards of its carpets were developed, and they continued on and on. In previous seasons we considered ourselves fortunate to find in this whole area even one scrawny patch of it

With the waning of the short alpine summer the remarkable though ever-changing show still continued. The lichens, now, came to attract more of our attention. This was not simply because the bloom of the wild flowers which earlier claimed most of our notice had now mostly passed their prime. Along the windward side of certain ridges, spots among the broken slates were ablaze with color The fragments of rock which we were loath to disturb by our footsteps were encrusted by red, orange, canary yellow, chartreuse, gray, black, and even blue, lichens, not only of unusually luxuriant growth but also of a greater diversity of kinds than I had hitherto seen in these places. Color, too, though from another source, was deepening in the meadows below us The rich purple of the soft, silky grass which we have come to call “Purple Mist” (Calamagrostis Breweri) because it was appropriately so described by John Muir, densely covered often very large areas, and showed by the uncommonly deep, rich color of its panicles an effect of a very dry year.

This closing note pointing out the drought conditions as being responsible for the unusual depth of color shown by the Purple Mist brings up the question as to why, despite the drought, was the growth and flowering so luxuriant in the other instances mentioned above. For this we had no answer. To be sure, it might be said it was the results of the scanty amount of winter snows and the lengthy drought conditons of the summer, but this explanation seems not altogether satisfactory. Anyway, it was a glorious alpine flower summer!

Next: Stock Use • Contents • Previous: Botanical History

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_nature_notes/47/3/flower_season.html