[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Nature Notes > 47(3) > With a Bee in My Bonnett and a Sandwich in My Pack! >

Next: Drought • Contents • Previous: Nursing Bears

Wilma Bouman

[click to enlarge] |

I suffer from that common disease called “looking at,” a disease Will Neely so clearly described in “Pine Trees, Barnacles and Everything” (Yosemite Nature Notes, 1977). However, now that I’ve completed six seasons in Yosemite’s granitic dome palaces under the influence of fiercely dedicated naturalists, I am beginning to feel at home in the mountains.

The beatific side of warm friendly slopes — their faces of the morning sun — is beginning to offset the cold and haughty grandeur of their evening side. Maybe this is a stage in convalescence; I feel the mountains are to be both loved and feared.

To help counteract the illness of just “looking at” nature, I have to keep telling myself that I must be part of nature and then the “unthinking, unformed moments” will enrich the mind and spirit as well as the senses. The song of the mountains will sing eternally in the ears, its imagery will be indelibly impressed so that it can be recalled at the touch of a wish.

One day I planned to hike to Young Lakes. I had no obsidian to trade with the Young Lakes Indians; no acorns to exchange; I mustn’t go just to “look at.” What then was to be my objective? Why, then I would see how far I could walk ire a day and thereby prove myself in other ways. Perhaps that, too, had its merits, at least as a physical feat.

So, on a clear, sunny August morning, I started out, sprightly of step and feeling, along with the postman of old, that “neither hail, nor sleet, nor dead of night” could stop me in my worthy endeavor, (although I wasn’t so sure about that “dead of night”).

Dark-eyed juncos “tched” encouragingly from trail-hugging shrubs; an occasional chickaree undulated across the path; the sun got hotter and hotter and finally forced me to put my sweater in my scanty-weight daypack.

There along the trail, just at its edge, grew a green gentian. It barely peeked-out as though apologizing for its dwarfish appearance. Unlike its tall showy sisters, this one was less than eight inches high. Perhaps it had been injured in some way, a naturalist later suggested. It looked like a single branch of a larger plant, a branch which had been thrust into the ground, later to take root and finally burst into a shower of green and lavender blossoms.

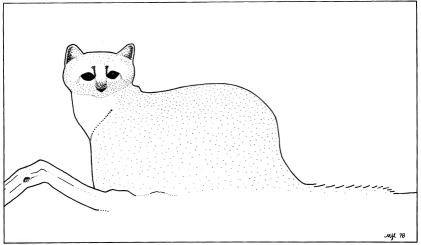

Taking the short trail to Dog Lake from the one encircling Lembert Dome, I froze in my tracks at the appearance of a Pine Marten who also froze on the spot, he eyeing me and I him. The fixed moment did not last long. I just had time to take in his overly long Siamese-catlike body, puppy-dog face, and bristling blackish tail — and then he was gone and yet he wasn’t gone! His weasel-like image continued to hang in the air like that of the Cheshire cat in Alice in Wonderland. Even today it refuses to fade.

It had been an exchange of “looking ats” and yet we were both part of the same small drama. What a wonderful beginning for a day’s hike that had only the counting of miles as its principal objective!

Dog Lake, hardly awake, was beautiful as it hung quiet in an early morning stillness. The desire to stay was there, but I couldn’t afford the time so pressed on toward Delaney Creek.

It is past the creek and in the Delaney Meadow, once one is clear of the forest, that one is forced to walk backwards. Here was a view that awed and overwhelmed. Here is the marvelous Cathedral Range of high sculptured peaks that begins well south of Mt. Lyell and continues the panoply in a majestic sweep that swings westward and then to the north around Ragged Peak and on eastward.

A series of shining white summits piercing a sky whose azure seems to soften the dazzle. But what are words? One can describe but not yet “see”; much like the old man in Robert Frost’s “The Mountain” describes the spring on the summit and then says he has never seen it. There are various ways of seeing.

But here one seems to stand in the presence of almost too much grandeur. To cut off such a view abruptly wouldn’t be at all fitting and so one leaves the place after several over-the-shoulder looks until one is swallowed-up in other scenery. And even the less dramatic scenery is eventually given up to that of foot-watching on stony ascents as one begins to circle Ragged Peak

After looking at the splendor of distant peaks — which gives a feeling of infinity and eternity — it is almost like holding a giant’s hand lens to one of them when you come in close to the vertical rising of Ragged Peak’s north side, its craggy character arranging and rearranging its mosaics from lake to lake to lake. Who can look at a mountain at such close range and not stand in awe?

The first lake, pooled in contentment, lay without a ripple; the second, like a small handmirror. But the third was larger, more cupped, more full of sky — to be inhaled like the scent of fine wine. There is something about a lake that is restful and cleansing, to be had by just looking at it. But viewing the lakes, after having been humbled by that grand display of peaks in Delaney Meadow, at least for me, was anticlimactic — a denouement in the day’s play come too soon. Still, one has to recognize that Nature does not arrange her drama by means of artifice. She may draw night’s curtain at the close of each day, but she fills each new day with dramas different from those of the preceding day. She seems to write an eternal epic poem for anyone who wants to wonder and be touched by it.

I had my first real rest as I dangled my feet in the water of the second Young Lake while I ate a sandwich and banana. “A well-earned rest,” I said to

[click to enlarge] |

Watching my feet over stony trails is a chore, but the descent around Ragged Peak had to be made. And who knows what joys may await the hiker on his homeward journey? So with that in mind, I picked up my lagging feet and flagging spirits.

Around the dome, just north of the Delaney Meadow, there was a sound: leaves rustled and feathers whirred as a great bird took off and soared directly over my head. It was a goshawk and, as I watched from so near, dazzled by the broadly barred gray and white wings and long tail, he set his course toward Glen Aulin. I sat down on the ground and said “Oh, Oh, Oh” to the skittering squirrels and stately pines — they were part of it all, noticing nothing strange on the scene — except perhaps me.

Now, for the entire stretch of the Delaney Meadow, I could walk right into that Cathedral Range experience and imagine Nature improvising a new symphony each day — in, out, and through those peaks and domes of golden splendor.

I rested once again at Dingley Creek and drank from its crystal stream which sang, muffled in an emerald scarf, brilliantly flowered with scarlet paintbrush. Its scarf, a grassy one shot through with reds, blues, and yellows of late flowering plants, was the one gay note carelessly slung across the harvest shoulder of that golden meadow. That bright ribboned stream of gurgling laughter cheered the heart and lifted the spirits.

Now the trail led into the forest again and, nearing Dog Lake, two mule deer, a doe and fawn, caught my eye and the three of us exchanged looks. None of us moved. I enjoyed their large ears, their liquid eyes, their curiosity. But what could I give them in return? After a minute or two I started softly yodeling to them; they seemed to like it. At least they stood a captive audience of two. Then I sang some old songs, including a Scottish one in memory of John Muir, and finally Old Hundredth, that grand old hymn that John Muir said had scattered his audience helter-skelter on the two occasions he sang it. My audience seemed to like that doxology: perhaps the musical taste of contemporary deer is less demanding.

Hiking alone has its perils as well as its joys. At one place on that memorable walk, a bird performed on me, the end result skittering across my glasses to end in a plop on my sleeve, an act so fast I had neither the time nor the inclination to try to “look at” the source of my discomfiture.

Another brief stop at Dog Lake. A cold chill shivering across its surface prompted me to put my sweater on again. And then, well before dark, I was back in camp and the number of miles I had trekked remains what it always was — a mere number to be tossed into the bucket of dull things along with tax receipts and other uninteresting facts and figures.

The wonders of that hike will continue to put a bee in my bonnet and a sandwich in my pack.

Next: Drought • Contents • Previous: Nursing Bears

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_nature_notes/47/3/hiking.html