historic resource study

VOLUME 2 OF 3

historical narrative

|

YOSEMITE

NATIONAL PARK / CALIFORNIA

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Resources > Chapter V: National Park Service Administration of Yosemite National Park, 1916-1930: The Mather Years >

Next: 6: NPS 1931 to 1960 • Contents • Previous: 4: Cavalry 1905-1915

|

historic resource study

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK / CALIFORNIA |

by

Linda Wedel Greene

September 1987

U. S. Department of the Interior / National Park Service

A. Overview 523

B. Roads, Trails, and bridges 531

1. Season of 1916 531C. Construction and Development 568a) Existing Roads and Trails 5312. Season of 1917 542(1) Government-Owned Roads 532b) Anticipated Visitation Requires New Construction 537

(2) Non-Government-Owned Roads 533

(3) Government-Owned Trails 533

c) John Muir Trail 541

3. Seasons of 1918-19 547

4. The 1920s Period 548a) Improvement of Roads and Trails Continues 5485. Some Valley Naturalization Begins 565

b) Hetch Hetchy area 550

c) Auxiliary Valley Roads 551

d) The Park Service Initiates a Road-building Program 552

e) Improvement of Wawona Road and Relocation of Big Oak Flat Road Contemplated 554

f) Reconstruction of Wawona Road Begins 555

g) Valley Stone bridges Constructed 560

h) Trail Work Continues 560

1. The Park Service Slowly Builds Needed structures 568D. Educational and interpretive Programs 595

2. A New Village site is Considered 577

3. The 1920s Period involves a Variety of Construction Jobs 581

4. The New Hospital and Superintendent‘s residence 585

5. The Indian Village in Yosemite Valley 590

6. More Construction and Removal of Some older structures 591

1. Nature Guide Service 595E. Concession Operations 612

2. LeConte Lectures 597

3. Yosemite Museum Association 597

4. Zoo 603

5. Indian Field Days 605

6. Interpretive Publications 606

7. Yosemite School of Field Natural History 606

8. Research Preserves 607

9. Development and Importance of Educational Work at Yosemite 607

1. The Desmond Park Service Company (Yosemite National Park Company) 612F. Patented Lands 677a) The Desmond Company Receives a Concession Permit 6122. The Curry Camping Company 652

b) Desmond Constructs forerunners of High Sierra Camps 615

c) Yosemite National Park Company formed 618

d) Bear Feeding Expands 624

e) High Sierra Camps Reestablished 626

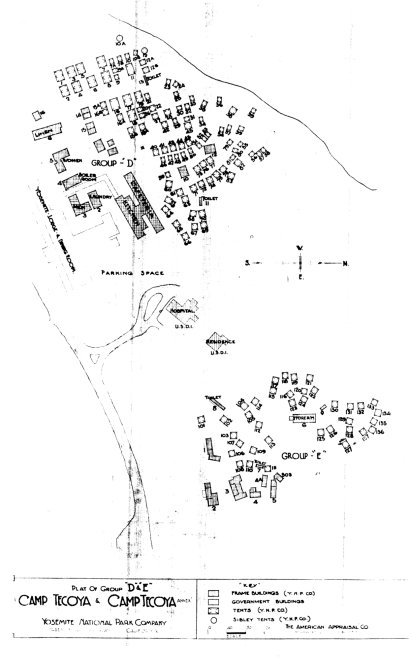

f) Yosemite National Park Company Holdings, 1924 630a) The Company Continues to Grow 6523. The Wawona Hotel Company 671

b) Mrs. Curry Has the LeConte Lodge Moved 652

c) New Construction activity 653

d) Yosemite Park and Curry Company formed 658

e) The Company initiates a Winter Sports Program 663

f) Concession Atmosphere Changes with Increased Tourism 671

4. Best Studio 675

5. Pillsbury Studio 676

6. Fiske Studio 676

7. Baxter Studio 676

1. Yosemite Lumber Company 677G. Hetch Hetchy 695

2. Foresta Subdivision 684

3. Big Meadow 687

4. Aspen Valley Homesites 687

5. Cascade Tract 688

6. Gin Flat and Crane Flat 688

7. The Cascades (Gentry Tract) 688

8. Hazel Green 688

9. White Wolf Lodge 689

1. Stream Control 715K. Fish Hatcheries 721

2. Meadows 717

3. Fire Control 718

4. grazing 720

Stephen T. Mather, having accepted the challenge of his old college friend Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane to take over the direction and unification of the national park system, devoted his next fourteen years to America’s national parks. Closely linked with Mather’s name during this period was that of Horace Albright, the young Interior Department lawyer who became Mather’s assistant. Mather served as Assistant Secretary of the Interior for two years, beginning in 1915, and as Director of the National Park Service from 1917 until 1929. Albright then served in that capacity until his resignation in 1933 to become president of the American Potash Company. During the crucial early years of the Park Service, Mather and Albright proved phenomenally successful in acquiring increased appropriations and the public support necessary to develop more and better park facilities:

Indeed the effectiveness of their promotion was not due to new ideas per se; John Muir, J. Horace McFarland, R. B. Marshall, Mark Daniels, and others had long since laid the rhetorical basis for justifying the national parks in an urban, industrial society. Mather’s and Albright’s original contribution was the institutionalization of the national park idea within the political and legal framework of the federal government. Henceforth an attack on a reserve would not be an affront to it alone, but to the very fabric of American society.1

[1. Runte, National Parks, 102.]

From the beginning, Mather determined to closely link in the public mind the relationship between national parks and the American economy. He believed it imperative to fully and efficiently develop park resources for the pleasure of the public, which would in turn result in profits for the public through increased tourist dollars. In view of the strong influence of utilitarian-minded preservationists, it seemed necessary in order to strengthen the position of the national parks to associate scenic protection with economic growth. Aesthetic conservationists still hoped to find ways to use scenic areas without destroying their basic values. They realized, however, that some concession had to be made to provide for the comforts and convenience of tourists in order to get them into the parks for longer periods of time so that they would come to appreciate them and rally to their defense.2

[2. See discussion of preservationist thinking after the Hetch Hetchy defeat and establishment of the National Park Service in ibid., 84-103.]

In his endeavors to popularize the national park idea, Mather’s practical business experience proved invaluable. He was, once again, selling a product to the American public, although scenic beauty would prove a somewhat harder commodity to sell than borax. Based on the argument that national parks would ultimately stimulate the economy if properly managed, Mather’s first steps involved streamlining his organization, handling estimates and appropriations in a businesslike manner, installing trained park personnel and nonpolitical superintendents, and improving the visitor experience by eliminating toll roads, admitting autos, improving accommodations, and inaugurating educational facilities and opportunities. His educational program became a direct outgrowth of this need to help people better understand the phenomena represented in the various national parks. The auto camps and housekeeping camps in the national parks resulted from his desire to provide accommodations for all classes of visitors. In Yosemite, ultimately, accommodations included the plush Ahwahnee Hotel, the medium-class Yosemite Lodge, the permanent tent camp at Curry, which also offered housekeeping facilities, and the seasonal camps of the High Sierra—ensuring something for everyone’s tastes.

One of the most important accomplishments of Mather’s tenure involved recognizing problem areas and organizational deficiencies and establishing divisions in his new bureau to address and correct them. Both Mather and Albright recognized the need for broader and sounder policies based on serious study of the issues and current data. One of the more important of these new divisions was that of landscape architecture, established to ensure the harmonization of park structures with their environment.3 That unique advisory group concerned itself with devising ways of constructing buildings, campgrounds, roads, and the like with minimal sacrifice of natural scenery. Their advice on engineering projects and other scenic questions, such as vista-cutting, would prove invaluable. The various chiefs of that division in Mather’s time—Charles D. Punchard, Daniel R. Hull, and Thomas C. Vint, all trained architects—accomplished designs of maximum harmony with the landscape using native stone and timber.4

[3. Horace M. Albright, “Stephen T. Mather—The Organizer of Parks,” 1932, typescript, 4 pages, in Central Files, RG 79, NA.]

[4. Shankland, Steve Mather, 254-56.]

The changes in Yosemite during Mather’s administration of the Park Service proved to be dramatic and beneficial to the visitor, many of them being precedent setting in terms of policy and programs. The purchase of the Tioga Road has been mentioned to improve access and sightseeing opportunities, as well as the establishment of the D. J. Desmond Company in an attempt to remove concession haggling and put Yosemite’s visitor services on a stable footing. Other significant actions from 1916 until his death included the improvement of roads, the relocation of Yosemite Village, construction of the Rangers’ Club—an architectural prototype for future park structures, and initiation of an interpretive and educational program that would be emulated by all other parks. Mather’s approach to the national parks is best described as visitor oriented. His attempts to increase the attractions of Yosemite resulted in the encouragement of

|

Illustration 66.

Automobile map of Yosemite National Park, 1917. From Report of the Director of the National Park Service, 1917 |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustration 67.

Automobile guide map of roads in Yosemite Valley, 1917. From Department of the Interior pamphlet, “Automobile Guide Map Showing Roads in the Yosemite Valley,” 1917. |

[click to enlarge] |

In 1916 Washington B. “Dusty” Lewis became the first administrator of Yosemite under the new National Park Service bureau. Originally with the U. S. Geological Survey, he became

one of the most popular superintendents in national-park history. A good engineer . . . handsome and personable and blessed with a handsome and personable wife, he was exactly what Mather wanted for Yosemite . . .5

[5. Ibid., 246.]

Lewis stayed in Yosemite for eleven years and guided into place many of the elements of today’s modern park system as conceived of by Stephen Mather.

1. Season of 1916

a) Existing Roads and Trails

In the fall of 1916 Washington B. Lewis, Supervisor of Yosemite National Park, sent the Superintendent of National Parks a list of all the existing roads and trails within the limits of the park:

[6. W. B. Lewis, Supervisor, Yosemite National Park, to Superintendent of National Parks, Department of the Interior, 28 October 1916, in Separates File, Yosemite-Roads, Y-20, #8, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center. (Lewis did not yet serve as superintendent of Yosemite National Park. Because Congress did not fund the National Park Service until 1917, a new organization could not be formed until that time, even though President Woodrow Wilson had signed the act creating the Park Service in August 1916.)]

b) Anticipated Visitation Requires New Construction

Both Assistant Secretary of the Interior Mather and Secretary of the Interior Lane determined early in 1916 that tourists should be induced to visit the nation’s parks, not only during but after the war. Mather, especially, recognized early the automobile’s potential to increase use of the national parks and thereby strengthen their position in American society. The Park Service eventually followed the policy that the minimum number of roads needed in a park would be built, but of as good a class as could be obtained. This would be, of course, dependent on government appropriations. To give the parks higher visibility, Mather conducted an educational campaign with the help of Robert Sterling Yard, former editor of The Century Magazine, and the Sunday New York Herald, and newly appointed publicity director for the parks. Until 1911, the Interior Department had only published park regulations and superintendents’ annual reports. Yard’s National Park Portfolio and a stream of enthusiastic articles dramatically increased travel to the parks during 1916.7 Mather and Lane believed that travel could be further encouraged by providing accommodations for tourists of all economic levels and perfecting means of travel to and through park areas.

[7. Mather and Yard later split over several issues concerned with park management. Yard criticized both Mather’s predator extermination program and the “honky-tonk” atmosphere of Yosemite’s concession operations. Fox, John Muir and the American Conservation Movement, 203-4.]

Road conditions in Yosemite at this time posed a major problem. Of the approximately 103 miles of road that the government controlled in 1916, only about one mile had a good hard surface. The two miles of “water-bound” macadam road on the valley floor contained bad ruts, while the approximately five miles of road surfaced with river gravel, which pulverized quickly under wear, required heavy sprinkling to keep down the dust. The remainder of the park road system consisted of narrow, dirt tracks with sharp curves and steep grades. Reconstruction of the El Portal road continued during this time. The one-way travel restriction on valley roads rigidly adhered to at the beginning of the 1916 season was gradually phased out as workers eliminated dangerous curves and widened narrow stretches. (One-way traffic continued to be enforced on the Big Oak Flat and Wawona grades because of their steepness.) Although speed limits remained in effect, every relaxation of restraints brought in more motorists who stayed longer. Park officials began suggesting at this time that the increasing travel required dignified gateways at the several entrances to the park, particularly where the Wawona, El Portal, and Tioga roads entered the boundaries. These would not appear, however, for several more years.

After improved roads brought them into the national parks and improved accommodations persuaded them to stay awhile, visitors would begin looking around for the best way to see the area’s sights. One of the primary emphases of the National Park Service in its early years in Yosemite concerned continuation of the backcountry trail-building program initiated earlier by Major Benson and carried out by Gabriel Sovulewski in an effort to introduce tourists to the backcountry. It differed from earlier army efforts in that trails were designed less for access and patrol purposes than for recreational use by tourists. Laborers placed trails in more scenic places, such as river canyons, and built them to higher standards, so that they often resembled roads in terms of width and method of construction. Explosives reduced labor costs and solved topographical problems. Modern machinery gradually facilitated trail construction and maintenance, and the earlier work in native stone and timber gradually gave way to steel, cement, and prefabricated wooden construction.

As workers dispensed with the old methods, however, characterized by skilled labor, hand tools, and draft animals, backcountry trail work became more environmentally incompatible. The new trails not only changed the character of backcountry use, but also severely impacted the ecology of the region. Little consideration existed for the effects of that type of trail building on the wilderness, and over the next several years, a variety of trails — relocations or newly built ones—began to impact the wilderness along with backcountry patrol cabins and High Sierra camps. Although occasional individuals raised questions about trail width and drainage and the long-term effects of construction activity in the backcountry, conservation of a pristine wilderness was not then the critical issue it is today, and attitudes changed slowly. Not until a new period of trail reconstruction and restoration began in the early 1970s, using a blend of old methods and tools and new ideas, did Yosemite backcountry trail work become flexible enough to adapt to the difficult problems posed by the rough Sierra terrain and inexpensive enough to be used under severe budget restrictions, while at the same time managing o to please wilderness lovers concerned with environmental compatibility.8

[8. See James B. Snyder and Walter C. Castle, Jr., “Draft Mules on the Trail in Yosemite National Park,” The Draft Horse Journal (Summer 1978): 10-13, for a detailed description of backcountry trail construction and maintenance techniques.]

In 1916 only about 175 of the 650 miles of park trail were considered in good condition, requiring only minor improvements. In fact some of the trails, such as those to Yosemite Fall, Nevada Fall, and up Tenaya Canyon, were considered of first-class construction. One hundred forty-five miles of park trail were judged only fair, while the remaining 280 miles needed reconstruction. Those were principally in the northern part of the park, north of the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne, an area just beginning to show measurable visitation. The park recommended three new trail projects: an extension of the Washburn Lake trail to join the Isberg Pass trail near Harriet Lake; a trail from the McClure Fork of the Merced, three-fourths of a mile above its junction with the latter, to Tuolumne Pass, via Babcock and Emeric lakes; and replacement of the trail from that same point of origin to Tuolumne Pass via Vogelsang Pass.9

[9. The former McClure Fork of the Merced River appeared as Lewis Creek on USGS maps in 1944. Named for W. B. Lewis, former park superintendent, it had been called Maclure Fork, the name also of a tributary of the Lyell Fork flowing from Maclure Glacier about one mile southeast. The new name eliminated some of the confusion engendered by the duplication. Decisions of the United States Geographic Board, No. 30—June 1932, Yosemite National Park, California (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1934), 14; Browning, Place Names, 134. The Board of Geographic Names ratified the name Vogelsang Pass in 1932, although it does not appear on maps. It is one-half mile south of Vogelsang Lake. Ibid., 228.]

During the 1916 season, laborers constructed about five miles of footpaths on the valley floor, primarily paralleling the existing roads but also closely following the contour of the land, so that they often possessed steep grades and sharp curves. As time passed and the roads were improved, sprinkled, and later paved, foot traffic became disinclined to use the paths and switched to the smoother roads. That did not pose a serious problem in the early days of light traffic, but as autos increased, the combination of hikers and motor cars on the roads began to cause problems. It ultimately became essential to provide paved walks alongside the roads in the valley.

During the 1916 and 1917 seasons, workers also laid out several miles of bridle paths on the valley floor. Those narrow trails again followed the contour of the country. Because they were dusty and only accommodated single-file traffic, horseback riders also began leaving the bridle paths and following the sprinkled, and later paved, roads, creating dangerous situations. At the same time, reconstruction of valley roads often wiped out many stretches of path. It became obvious the park needed a more modern system of horse routes.

Bridges in the valley posed another problem. In 1916 only the El Capitan Bridge, a combined steel and wood truss structure, had a safe loading capacity of more than six tons. Sentinel Bridge, on the other hand, over which most valley traffic passed, had been condemned three years earlier for loads over three tons. This caused great inconvenience to the park maintenance staff, because heavy road building and sprinkling equipment could only pass from one side of the valley to the other over the El Capitan Bridge. That resulted in excessive cost to transportation companies in the park as well, who had to send all freight trucks and heavy passenger vehicles bound for destinations on the north side of the valley via the LeConte Road and Stoneman Bridge—an extra two-mile haul.

c) John Muir Trail

Work on the John Muir Trail continued in 1916, during which time crews began working up the Middle Fork of the Kings River to a point just south of Muir Pass. In 1917 a $10,000 appropriation enabled construction of two bridges across the San Joaquin River and more work south of Muir Pass. Although the 1919 and 1921 legislatures voted additional appropriations, Governor Stephens vetoed both measures and work stopped. No more funds came until 1926, which subsidized seventeen more miles of trail north from the Selden Pass area. In 1927 and 1929 crews accomplished trail work across Silver Pass, Fish Creek, and past Virginia and Purple lakes to Devils Postpile National Monument. The stretch of trail from Crabtree Meadows to the summit of Mt. Whitney was completed during 1930. Work also began that year on a new, more direct crossing of the Kings-Kern Divide at Foresta Pass, boundary between Sequoia National Forest and Sequoia National Park. The original route selected by McClure had been followed closely, with only minor relocations.10

[10. Roth, Pathway in the Sky, 44; Huber, “The John Muir Trail, “41-5]

2. Season of 1917

The year 1917 proved important in Yosemite history, producing general improvements parkwide relative to roads and trails, visitor accommodations, travel facilities and transportation services, campgrounds, and utilities and sanitation. Those accomplishments had been made possible by an increase in tourism, resulting in greater revenues, and by larger congressional appropriations as that body responded to the mounting popular interest in national parks. Officials expended the bulk of the funds available in 1917 in construction, maintenance, and improvement of the park road and trail systems, both on the valley floor and in outlying areas. Several thousand dollars enabled continuing work on the El Portal road, which would connect at El Portal with a road constructed by the state and cooperating counties as part of the state highway system. In connection with that work, in 1917 the lower wooden timber truss bridge over Cascade Creek, built in 1907-1908, was replaced by a concrete structure. The upper bridge, built at the same time, was also in process of replacement.

Another benefit accrued to Yosemite travel in the summer of 1917. At that time the Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Company turned over to the Department of the Interior, in return for certain transportation privileges in the park, title to the Wawona toll road system connecting Wawona with Fort Monroe, including its lateral to Glacier Point from the old Chinquapin stage station. The department then eliminated travel charges, except for the automobile fee.11 The Mariposa County Board of Supervisors declared the Coulterville Road free to the public about 1917, and performed a small amount of improvement work on it over the next two years. Later the former owners won back title to the road, but subsequently did not make repairs or collect tolls. Ultimately the portion of that road inside the park became abandoned. Mariposa County continued to maintain the road outside the park, from Coulterville to Hazel Green and Crane Flat.

[11. Report of the Director of the National Park Service, in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1917. Volume 2. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. ‘(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1918), 841-49.]

During this 1916 to 1930 period, California’s highway system was undergoing rapid development and improvement for automobile traffic. When the federal government took over the Big Oak Flat and Tioga roads in 1915 and the Wawona Road in 1917, it made only such improvements as seemed necessary to make them passable. As fast as money could be obtained from Congress, those mountain roads, which obviously were not suitable for the increased auto travel using them, were improved. As stated earlier, prior to the late 1920s, roadwork consisted only of repair, maintenance, and minor improvement because of the expense of paving and lack of sufficient appropriations. The improvements were undertaken in connection with maintenance work only and primarily involved widening the roadway to provide turnouts so that two cars could pass, reduction of some of the sharpest curves and steepest grades, and replacement of old cutouts and bridges. No funds existed to relocate or rebuild roads.

Tourist visitation to Yosemite had always occurred on a seasonal basis. By long tradition, Yosemite’s waterfalls had been a major spring

|

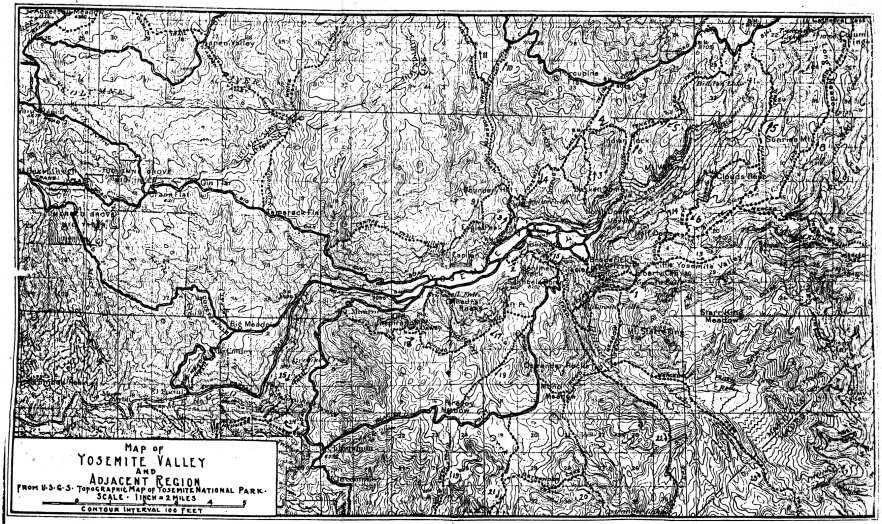

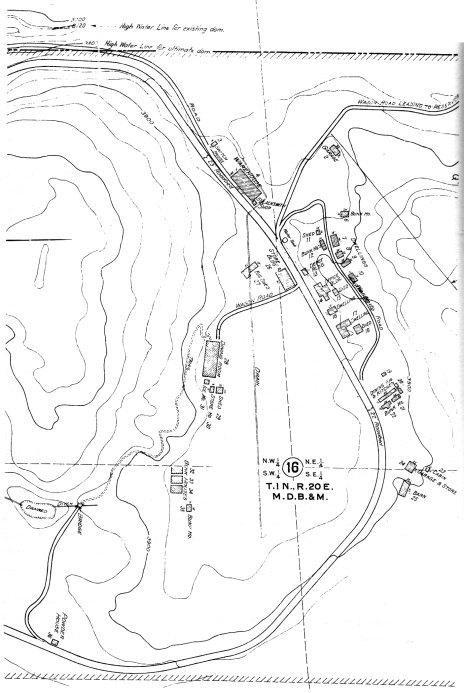

Illustration 68.

Map of Yosemite Valley and adjacent region. Note the Carlin Trail, used by cattlemen, from Aspen Valley to Ackerson Meadow. Hall also mentions a seldom-used “Packers’ Trail” beginning about one mile north of Aspen Valley and bearing north to Hetch Hetchy. From Hall, Guide to Yosemite, 1920. |

[click to enlarge] |

3. Seasons of 1918-19

By 1918 practically all the primary park roads had been gravel covered and widening and straightening of routes had begun. During the 1918 season, construction began on three new trails: because snow often covered Vogelsang Pass, crews constructed an alternate route between Merced Lake and Tuolumne Meadows via Babcock and Emeric lakes to the divide at Tuolumne Pass; another new trail left the Tioga Road at the Yosemite Creek bridge and proceeded eight miles to Ten Lakes Basin on the south rim of Tuolumne Canyon; the last, the Ledge Trail, climbed Glacier Point behind Camp Curry, an improvement of the earlier, exceedingly steep trail that nevertheless cut the distance between the valley and Glacier Point to less than two miles. Finally in 1918 workers built a new Sentinel Bridge across the Merced River just east of Yosemite Village. Of reinforced concrete beams and native granite, the three-span, two-lane bridge measured ninety-seven feet long and twenty-three feet wide. The superintendent noted during that season increased visitor appreciation of the high country north of the valley, as evidenced by extensive camping throughout the higher mountains.

In the 1919 season the Sierra Club enabled climbers to more easily scale Half Dome by providing a stairway to the summit. It consisted of two sections, the first a 600-foot stretch of zigzag trail and stone steps on the small dome. On the second, 800-foot section up the incline on the large dome, a double handrail of steel cables set into a double line of steel posts set in turn into sockets drilled in the granite every ten feet assisted the ascent. Experts from the Sierra Club accomplished the work with the park meeting part of the expense.

4. The 1920s Period

a) Improvement of Roads and Trails Continues

Trail marking has always been a difficult task. The state of California had used painted signs, white on blue and green on white, to mark trails. Many of these continued in use into the late 1920s. Possibly because of the loss of several of them, the civilian rangers began tacking shakes to trees at each trail junction displaying directions printed on them with lumberman crayons. The Sierra Club marked trail junctions with painted coffee can lids in the mid-1920s to make them easier to find. In the 1920s trail measuring involved attaching an odometer to a bicycle wheel. A long handle attached to the spokes reached to the saddle. Subsequent marking involved nailing small round tin tags with numbers and letters on them identifying specific trails. In 1927 the Park Service made green signs of porcelain-covered metal. A few of these still mark restrooms and maintenance roads. In 1930 the old signs at the Mariposa Grove were removed and replaced with wooden slabs bearing the names of important trees and necessary statistics.

During the 1920-21 season, work crews completed trails from Harden Lake on the Tioga Road to Pate Valley in the bottom of the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne River and down that canyon from Glen Aulin to the lower of the Waterwheel Falls. In addition to constructing trails in the Tuolumne Canyon, laborers completed two bridges for saddle and pack animals: a fifty-foot double-span one at Glen Aulin seven feet wide and a fifty-five-foot single-span one at Pate Valley also seven feet wide. A masonry-faced arch bridge over Yosemite Creek in Yosemite Valley and a reinforced concrete beam bridge over the Merced River near Happy Isles were among the improvements of the 1921 fiscal year. The North Road across El Capitan Meadow was raised in 1922 to prevent its flooding and the road from Camp Curry over Clark’s Bridge to Mirror Lake was widened in 1923.12

By 1923 the highway from Merced to the gateway of Yosemite National Park had been paved through Merced County and graded and graveled in Mariposa County to its termination at Briceburg.

[12. Fitzsimmons, “Effect of the Automobile,” 54. See Hall, Guide to Yosemite, for a description of roads and trails at that time.]

In 1924 the California State Highway Commission installed a convict camp at Briceburg on the Merced River, whose residents began construction on the last seventeen-mile section of the Ail-Year Highway to El Portal. Also that year the park reopened the section of the Pohono Trail between Fort Monroe and the Pohono Bridge that had been abandoned for many years. This action enabled visitors from the valley to make the trip to Glacier Point on foot or horseback without using the Wawona Road. A new bridge on the trail was erected over Bridalveil Creek. This same year workers cut a stone stairway out of the rock wall to replace the wooden stairs on the Vernal Fall Mist Trail. Laborers also finished most of the trail from Pate Valley to Waterwheel Falls through the Tuolumne Canyon that year. In addition they built a new two-span bridge over the Tuolumne River on the trail to Soda Springs, a single-span structure over Rodgers Canyon Creek on the Tuolumne Canyon trail, and a bridge over Return Creek. The park also reconstructed approximately three miles of the Mariposa Grove road system, while the remaining three miles remained essentially as when constructed in the 1870s. In 1925 trail crews completed two miles of new trail from the junction of the Pohono Trail at Bridalveil Creek on the south rim of the valley to the junction of the Glacier Point-Wawona trail via Alder Creek. A branch extended to Bridalveil Meadow and the Glacier Point road. By April workers had almost completed the trail through Muir Gorge so that hikers could pass from Waterwheel Falls down the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne to Pate Valley. (The Sierra Club had regularly used this canyon trail for years and had marked their own route and installed a register at Muir Gorge.) An improved trail through there had been one of John Muir’s greatest wishes, and through the urging of the Sierra Club, Director Mather had become interested in the project, construction of which had been directed by Gabriel Sovulewski. The Tuolumne Canyon trail was finally completed in September. New bridges included one on the Snow Creek Trail, one for saddle and pack animals over a branch of the Tuolumne River at Pate Valley, and another one over Rancheria Creek on the trail to Tiltill and Hetch Hetchy valleys.

b) Hetch Hetchy Area

Another problem that Mather faced near the start of his parks administration revolved around the city of San Francisco’s road and trail responsibilities under the Raker Act, which city and county representatives had in 1913 declared their willingness to perform. After the war Mather began insisting that the city meet its obligation by constructing good concrete roads. He and City Engineer O’Shaughnessy talked considerably of the matter but had not resolved the impasse by the time of Mather’s death in 1930.

During the summer of 1925 the board of supervisors of the city and county of San Francisco passed a resolution directing the city Board of Public Works to remove the Hetch Hetchy Railroad tracks and related apparatus between Mather and Damsite and to resurface the roadway to make it available for vehicular traffic. The park deemed this an important action from an administrative standpoint and also to open up the northern part of the park to tourist travel. Since June 1923, according to park superintendent W. B. Lewis, the railroad had only been used for propoganda purposes, bringing in people who used the city’s services to impress them with the importance of the reservoir as a water supply and to build up public opinion against utilizing the Tuolumne watershed for tourist purposes. The Park Service then wanted the city to construct a scenic road around the north side of the reservoir (never constructed) to provide access to the trail system leading up the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne and into the northern part of the park.13 The Park Service and the city decided not to allow tourist travel over the steep and narrow roadbed from Hetch Hetchy to Lake Eleanor, which contained dangerous switchbacks. On 19 September 1925 the new nine-mile auto road between Mather Station and the Hetch Hetchy dam officially opened to the public, an event regarded as heralding a new era of development for the Hetch Hetchy region.

[13. W. B. Lewis, Superintendent, Yosemite National Park, to the Director, National Park Service, 18 May 1925, including “History of Hetch Hetchy Project,” typescript, 14 pages, in Box 84, Hetch Hetchy “Gen’l 1923-24-25,” Yosemite Research Library and Records Center, 13.]

c) Auxiliary Valley Roads

The auxiliary valley roads received little attention prior to 1920 when the park constructed a new road behind the present New Village to the government barns and storehouse. Also that year a new road was completed west of Yosemite Lodge and in 1921 an access road was provided for new employee cottages.14 In 1919 the Mirror Lake road had been realigned. The road through Camp 7 was built in 1921, dissecting the camp, and another ran across Cook’s Meadow by 1924.15 The New Village construction of the mid-1920s resulted in additional road building in that area, including auxiliary roads to the government barns, shops, and housing. Roadways in the campgrounds were also extended in the mid 1920s. The alternate route to the Old Village—the south branch of the South Road—became an auxiliary route as traffic to the Old Village decreased. The most significant era in increasing total miles of auxiliary roads occurred from 1929 to 1938. Final construction of auxiliary roads in the lower valley included a new route to the river from the North Road at the east end of El Capitan, a new road into Bridalveil Meadow, and an access road to the new sewage plant opposite Bridalveil Fall. The alternate route to the Old Village site was finally eliminated.16

[14. Fitzsimmons, “Effect of the Automobile,” 57.]

[15. Ibid., 51.]

[16. Ibid., 58-59.]

One of the main objectives of the development program initiated by construction of the New Village was to move facilities off the main valley highways. ‘The present main circuit roads on both sides of the valley and crossing the valley resulted from this planning. The new Ahwahnee Hotel would be placed on a spur road. The new South Side Road was built at a distance from Camp Curry with a spur road into the camp. In the same way, the New Village was built on a loop road so that only those desiring services there had to enter the area. The main road bypassed that village.17

[17. Frank A. Kittredge, Superintendent, Yosemite National Park, Memorandum for the Regional Director, Region Four, Re: Development in Yosemite Valley, 25 June 1947, in Box 78, “Box A-NPS Files,” “Development - Part IX,” Yosemite Research Library and Records Center, 2.]

d) The Park Service Initiates a Road-Building Program

By 1924 Yosemite auto travelers still suffered over 138 miles of rutted wagon road, as did visitors to all of the national parks. Puny Congressional appropriations over the past several years did not begin to cover the costs of maintaining or building roads in rugged mountain terrain, during short working seasons, and under the extreme care that had to be taken to preserve scenic values. By 1924, however, need for better roads had become acute. Finally, after some astute lobbying, the 1924 Congress voted the Park Service its first real road-building authorization — seven and a half million dollars for a three-year program. Although this appropriation would not begin to cover the cost of roads of the standard needed in the future, Mather intended to use the money as far as it went to improve current roads by widening, reducing grades, and eliminating curves, and to build roads in parks where none existed.

All national park road planning since 1917 had emanated from the office of George E. Goodwin, Chief Engineer of the National Park Service in Portland, Oregon. Around 1925, however, the Park Service and the Bureau of Public Roads made an agreement under which major park roads would be built and maintained. The Bureau’s Senior Highway Engineer Frank A. Kittredge, who ultimately became Chief Engineer of the Park Service after Goodwin’s departure, and also liaison with the Bureau of Public Roads, drew up in 1926 a road program for the entire National Park System.18 Because of the great increase in travel to national parks and because the State Highway Commission was building roads leading to Yosemite to a higher standard than those the park had originally contemplated, the construction program had to be revised and a policy adopted of building within the parks roads of the same standards as those leading into them.

[18. Shankland, Steve Mather, 152-59. Herb Evison pointed out the type of relationship that existed between the Bureau of Public Roads and the National Park Service:

. . . almost from the beginning, the maintenance of close relations with the Bureau [of Public Roads] has been a function of landscape architecture rather than engineering. The competence of Bureau engineers has seldom been subject to question; on the other hand, Service concern in road design and in road construction practices has been with fitting these “necessary evils” into the landscape with the least damage, unobtrusively, softening the lines of demarcation between road construction and the bordering undisturbed landscape.

This has called for the special skills of the landscape architect. Thus the flattening and rounding of cut slopes, the provision of natural-looking vista clearing, and the wedding of the road margins with the adjacent land through carefully planned planting of native vegetation have given a special and widely copied character to park and parkway roads.

S. Herbert Evision, “The National Park Service: Conservation of America’s Scenic and Historic Heritage,” 1964, typed draft, 663 pages, in Library and Archives, Division of Reference Services, Harpers Ferry Center, Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, 454.]

In 1925 then, Director Mather announced a radical change in the Yosemite road building program, including immediate steps to relocate both the Wawona and Big Oak Flat roadbeds to provide a gentler grade and to realign and reconstruct the Tioga Road. Mather stated that the Park Service intended to build the best mountain roads that money and the science of highway engineering could devise. This was obviously in response to the imminent completion of the All-Year Highway, which park officials realized would cause an immense influx of new visitors and severely impact the substandard park roads. Beginning in 1925, work began on widening, improving, and paving the El Portal road while park crews prepared a site for a ranger station/residence and checking stations at Arch Rock to serve the expected flood of visitors upon the opening of the All-Year Highway. The road below the checking stations had to be widened to accommodate four lanes of traffic in 1928. Two roads connecting the North and Middle (Ahwahnee) roads in the valley were built in 1925. Other accomplishments around that time included completion of the Camp Curry bypass road and relocation eastward of the El Capitan Bridge and its approaches.19

[19. Fitzsimmons, “Effect of the Automobile,” 51.]

e) Improvement of Wawona Road and Relocation of Big Oak Flat Road Contemplated

In 1926 the National Park Service and the Bureau of Public Roads signed a Memorandum of Agreement for the construction of major roads within the national parks. In California, the district engineer of the bureau in San Francisco assigned an engineer to do reconnaissance work in Yosemite and lay out an integrated road system enabling future work to be planned properly and undertaken systematically. The Bureau of Public Roads representative, Harry S. Tolen, first surveyed the Wawona Road, the most heavily travelled route in the park prior to completion of the Ail-Year Highway. Except for widening of the grade between the valley floor and Inspiration Point in 1924, and occasional drainage work, the road had never been improved.

Tolen found that the section of the Wawona Road between Yosemite Valley and Grouse Creek, which passed over the mountain at Inspiration Point, would never be a satisfactory grade. The point’s height above the valley floor and the short distance from there to Bridalveil Creek necessitated a very steep grade that would be hazardous during the winter months. After detailed study of that portion of the Wawona Road, Tolen determined that a satisfactory grade could be obtained only by running the road along the bluffs. Because of their steepness, it would be necessary to drive a tunnel through them, an innovation in highway construction in the parks. It would take two years to reach a decision on the location of this portion of the Wawona Road.

The Park Service determined to relocate the Big Oak Flat Road between Crane Flat and Yosemite Valley farther to the south, shortening the distance between the valley floor and Crane Flat and enabling it to be opened earlier in the spring. It proposed to abandon the Tioga Road from Crane Flat to Carl Inn and from Carl Inn to White Wolf and substitute a new alignment directly from Crane Flat to White Wolf via the upper reaches of the South Fork of the Tuolumne River. That would shorten the route to Tuolumne Meadows, save elevation, and provide a high-standard road.

f) Reconstruction of Wawona Road Begins

An event destined to have a major impact on tourist visitation to Yosemite took place on 31 July 1926—the official opening of the new Yosemite Ail-Year Highway to motor travel—a celebration coinciding with the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Mariposa Battalion’s discovery of Yosemite Valley in 1851. The most important roadwork achieved during that time involved paving of the valley roads by the Bureau of Public Roads from 1927 through the early 1930s. The new roads greatly facilitated the park maintenance schedule by requiring less repair, less gravel to be dredged from the Merced River, and less sprinkling. This in turn released park crews and equipment for other necessary jobs. The rebuilding of the road system in the 1920s and the paving revolutionized travel conditions in the valley. It not only brought in increasing numbers of visitors, but made traveling safer and more pleasant, and improved scenery and vegetation along the roadside that was no longer obscured by the dust of passing autos. “The one act of rebuilding and paving the roads probably did more to return the Valley to its natural appearing condition than anything since the stagecoaches first churned up the dust many decades before.”20

[20. Kittredge memo to Regional Director, 25 June 1947, 3.]

In the summer of 1927 the Park Service assumed maintenance of the road between Mather Station and Hetch Hetchy and began to issue auto permits and collect fees. The good condition in which the park maintained the Wawona, All-Year, Big Oak Flat, and Tioga roads during this time resulted in a remarkable increase in travel to the park. On the valley floor road crews made good progress toward completing paving of another thirteen miles of roads, resulting in a total of twenty-nine miles of paved major roadways in the valley. The park opened four miles of oil macadam surfaced road between Yosemite Village and El Capitan Bridge.

Also that year the Park Service started planning for five new bridges in the valley. Two would replace the Pohono and Clark’s bridges, two would cross the Merced River near Kenneyville, and one would be a new bridge over Tenaya Creek. In accordance with President Wilson’s executive order of 28 November 1913 requiring that, whenever artistic questions arose on federal projects, proposed plans be submitted to the National Commission of Fine Arts in Washington, D. C., for comment, a committee of that commission considered the Yosemite bridge designs. Director Mather believed that the design of bridges in national parks was one of the Park Service’s most important architectural problems. Because some existing structures in parks had drawn considerable criticism from architects, landscape engineers, and others, Mather determined to achieve in the future the best possible structures in terms of both design and execution for particular location.

Trail and associated bridge work continued in 1927. Crews constructed two bridle bridges over the lower and upper crossing of McClure Fork on the trail to Washburn, Babcock, and Boothe lakes. They also rebuilt the bridge over Illilouette Creek on the Vernal and Nevada falls-Glacier Point Trail at a new location upstream. Yosemite National Park’s first nature trail was laid out in Yosemite Valley in 1927, succeeded by a permanent trail in 1929. Clifford Presnall developed this “Lost Arrow Nature Trail, “which was used until 1933. Presnall also developed nature trails along the Sierra Point and Ledge trails, the latter abandoned after two seasons due to vandalism.21

[21. Richard R. Wason, “Yosemite Nature Trails,” Yosemite Nature Notes (September 1953).]

In 1928 Director Mather and the Bureau of Public Roads decided to begin reconstruction of the Wawona Road, postponing relocation of the Big Oak Flat Road at least one year. They made that decision for several reasons: first, the state had no immediate plans to construct the Buck Meadows-Crane Flat link that would insure that the entire Big Oak Flat Road could be used within a reasonable period of time after the park had completed its section; second, the road work around Hetch Hetchy required of the city of San Francisco under the Raker Act had to be coordinated with the Big Oak Flat Road work, and so far the city had given no indication as to when it would carry out the requirements; and third, more time was needed to work out landscape details on the Big Oak Flat Road where it ascended the north wall of the valley to prevent marring of the cliffs. The Park Service believed that a timely reconstruction of the Wawona Road would result in some immediate benefits to the park. The improved road would make the Mariposa Grove an all-year attraction, add to the winter sports lure of the park, and open up camping areas along the Glacier Point road that would relieve the crowded conditions in the valley. 22

[22. Stephen T. Mather, Memorandum Re Wawona and Big Oak Flat Roads, 19 April 1928, in Central Files, RG 79, NA.]

|

Illustration 69.

Happy Isles Bridge, built 1929. Note tunnel for bridle path Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1984. |

[click to enlarge] |

g) Valley Stone Bridges Constructed

By the end of 1928 a system of hard-surfaced roads extended over the valley floor, necessitated by the increased travel due particularly to the opening of the Ail-Year Highway into the park. Road work at this time included the five bridges mentioned earlier. A total of eight granite-faced, concrete arch bridges were constructed on the floor of Yosemite Valley between 1921 and 1933. All were of similar design, with variations in size and configuration. Built of reinforced concrete veneered with native granite, they each had either one or three arches with finely cut keystones. The structures include the Yosemite Creek Bridge built in 1922; the Ahwahnee Bridge (Kenneyville #1), crossing the Merced on the Mirror Lake Road; Clark’s Bridge, crossing the Merced on the Curry stables road; the Pohono Bridge, crossing the Merced at the beginning of the road to El Portal; the Sugar Pine Bridge (Kenneyville #2), crossing the Merced on the Mirror Lake road; and the Tenaya Creek Bridge, all built in 1928; the Happy Isles Bridge built in 1929, which had underpasses on each side of the river for bridle paths; and the Stoneman Bridge, built in 1933. Designed by the senior highway bridge engineer of the U. S. Bureau of Public Roads in collaboration with the Landscape Division of the Park Service to accommodate all classes of traffic and to harmonize with their natural surroundings, they had been endorsed by the National Commission of Fine Arts. In 1928 workers also replaced two bridges on the Tioga Road, one at the Yosemite Creek crossing and the other at the lower crossing on the Middle Fork of the Tuolumne River, and constructed a bridge across Cascade Creek on the Big Oak Flat Road.

h) Trail Work Continues

Because of a lack of funds and as a matter of general policy, the Park Service during the mid- to late 1920s did not feel justified in building separate trails for hikers and riders, but followed the practice of building trails suitable for both classes of travel. The bulk of trail construction at that time concentrated on dust-proof paths. During 1928-29 workers built three or four miles of dust-proof trails to points of interest along the valley walls, reaching elevations sufficient to enable extensive views of the valley. One such path extended through the Lost Arrow section to the foot of Yosemite Fall, another led to the Royal Arches, and another climbed to a lookout point above and west of Camp Curry. During 1928 the Park Service reconstructed the Four-Mile Trail some distance from the old one as well as several sections of bridle path in the valley. Other work included reconstruction of the Mist Trail, mostly along its old route. Steps had been installed in the steep areas, and a pipe rail was to be placed along the most dangerous portions of the trail by 1929.

During the 1928-29 travel season in Yosemite, the Park Service noted a year-round movement of people rather than just summer visitation. Winter sports played a large part in attracting visitors during what had once been considered a dull season in Yosemite. The improvements made to roads entering and in the valley also increased the popularity of valley travel. The Big Oak Flat Road from Gentry to Gin Flat was being widened, surfaced, and dustproofed. Some curves and grades were reduced at the same time. At the same time, the Park Service and the concessioner slowed their building programs, both organizations believing that development on the valley floor had reached its peak. By 1929 the valley contained twenty-nine miles of paved road; ten miles of bridle paths; fifteen miles of paved walks; fifteen miles of oiled roads; six new road bridges; two large, paved parking areas (at Happy Isles and Mirror Lake); and several small footbridges across the Merced River (between camps #12 and #14, camps #7 and #16, camps #6 and #16, and between old Camp Ahwahnee and Yosemite Lodge).

In addition to continuing work on the Four-Mile Trail in 1929, crews rebuilt and shortened the Merced Lake trail between the valley floor and the lake. They also improved the Vogelsang Pass trail from Merced Lake to Tuolumne Meadows, which had been abandoned a few years previously because of its dangerous condition. Laborers then relocated the Firefall Point foot trail near Glacier Point and built a masonry wall at Firefall Point. Four new trail bridges were built in 1928-29, and workers replaced the old Vernal Fall bridge of the Glacier

|

Illustration 70.

Map showing roads in Yosemite Valley, ca. 1929. Central Files, RG 79, NA. |

[click to enlarge] |

5. Some Valley Naturalization Begins

During the 1930 season, a crew began obliterating old roads across the meadows on the south side of the valley floor, changing them whenever possible into bridle paths, and then landscaping the area. The digging of ditches to prevent autos from driving across meadows in the valley helped improve the park’s appearance. In April 1930 the collapse of the upper member of its western truss destroyed the El Capitan Bridge, constructed in 1915. Park officials immediately condemned the structure and barricaded the road. They proposed installation of a new structure one-half mile east of the old site. Workers restored the site of the old bridge to as natural a condition as possible as part of an ongoing program to obliterate the most unsightly spots on the valley floor.

Bridge construction in the 1930 season included replacement of the Silver Apron Bridge below Nevada Fall with a new log structure, repair and reconditioning of the Swinging Bridge in the valley, and replacement of one span on the footbridge to Yosemite Village. Laborers also installed a bridge on Tenaya Creek above Mirror Lake in connection with a new trail there.

|

Illustration 71.

Map of Yosemite National Park, 1929. From Circular of General Information Regarding Yosemite National Park, California (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1929). |

[click to enlarge] |

The new Four-Mile Trail (actually 4.62 miles long) was completed in June 1930. The trail crew then moved to Nevada Fall to begin work on that section of the Merced Lake Trail. That work involved relocating and reconstructing the old trail from Happy Isles, past Vernal and Nevada falls, through Little Yosemite and Lost valleys, to Merced Lake. In places where workers had to cut into the granite ledge, they treated the walls chemically to restore the color. A trail change also took place near Boothe Lake after the Curry Company moved its hiker’s camp east to a point near Upper Fletcher Lake for sanitary reasons. Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur authorized the city of San Francisco to begin construction work on the scenic trail around the north side of Hetch Hetchy reservoir from O’Shaughnessy Dam to Tiltill Valley and Lake Vernon in 1930. In connection with that project, bridges were constructed across Tiltill and Falls creeks.

1. The Park Service Slowly Builds Needed Structures

Building construction progressed slowly in Yosemite during the first few years of Park Service administration. Immediate reasons for the lack of development included division of the nation’s attention and resources to the World War I effort and the multitude of organizational and funding questions confronting the new bureau’s leadership. At the same time, the Park Service needed to formulate a clear, long-term development policy before expending vast sums of money on construction. During the winter of 1915-16, the wagon shed used by the Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Company in Yosemite Valley collapsed under the weight of heavy snows and was damaged beyond repair. In the spring of 1916 the company gained permission to erect a portable office building in the valley.23 Up until 1917 the area between the later New Village and the north valley walls and between Yosemite and Indian creeks held few permanent structures. Beginning in 1917 the government constructed a complex of service buildings north of the cemetery, including barns, shops, and storage sheds.

[23. Gabriel Sovulewski to Yosemite Stage & Turnpike Co., 14 March 1916; W. B. Lewis, Supervisor, to S. G. Owens, Manager, Yosemite Stage & Turnpike Co., 18 April 1916, in Box 63, Yosemite Stage & Turnpike Co., Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

The first housing for government employees in Yosemite consisted of the cottages formerly used by the War Department at Camp Yosemite—renamed the Yosemite Falls Camp, which had been sealed to make them usable during the winter season. Government barns and a wagon shed, frame with shakes, were built in 1916. A new schoolhouse built in 1917-18 accommodated fifteen to twenty pupils, mostly children of government personnel, although the children of park concessioners and their employees attended it in the early fall and late spring. It stood near the northeast corner of Hutchings’s old farm. Laborers also erected a machine shop near the other government shops and barns during the 1917-18 season. In June 1917 the park established a government mess. After one summer in the inadequate tent quarters, however, the operation moved into the old Jorgensen cabin near Sentinel Bridge, which the artist had vacated after relinquishing his concession. A committee of three men appointed by Superintendent W. B. Lewis made the studio into a clubhouse for members of the mess by converting it into a kitchen and dining room.

The Sundry Civil Act of 1 July 1916 contained $150,000 for the erection of a new power plant in the park. Park officials considered the plant an absolute necessity because of increasing demands for power, light, and heat by the park concessioners. The sale of electric current would also provide substantial revenue for the park. In general, the Interior Department believed that the federal government should own and control power plants, water and sanitation systems, and telephone lines in national parks so that concessioners could invest all their money in further development of their own enterprises and because, as public

|

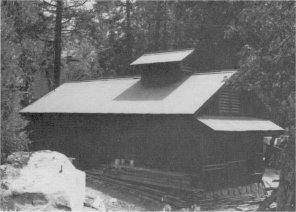

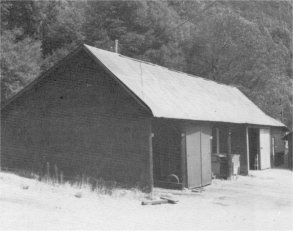

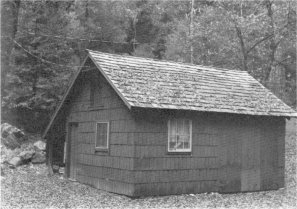

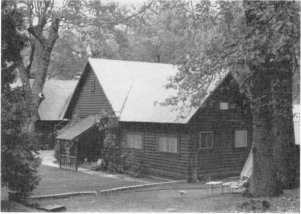

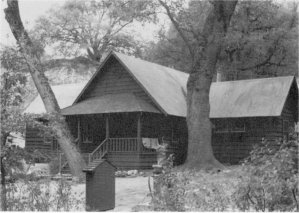

Illustrations 72-73.

Examples of early structures in Yosemite Valley maintenance yard. Photos by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984. |

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

|

Illustrations 74-76.

Water intake and penstock of Yosemite Valley power plant. Photos by Gary Higgins, 1984. |

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

|

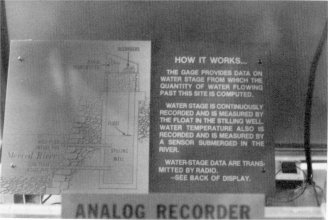

Illustrations 77-79.

Interior of powerhouse and Cascade residence #101 and garage #333. Photos by Gary Higgins and Robert C. Pavlik, 1984. |

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

[click to enlarge] |

[24. Information on 1916 NPS activities is found in “Report of the Superintendent of National Parks” and “Excerpts from reports of supervisors of national parks” in Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1916. Volume I. Secretary of the Interior, Etc. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1917), 762-63, 789-94.]

The park located the small diversion intake dam for the plant at the head of the rapids in the Merced River near the Pohono Bridge and the powerhouse near Cascade Creek, the latter designed to be as inconspicuous as possible. When completed, the plant would generate enough power to light all Park Service buildings, all camps, the new hotel, and all the main roads and footpaths in the valley. It would also provide for heating and cooking at the hotel and permanent camps. The Interior Department carried out the work under the supervision of the Superintendent of National Parks, through Galloway and Markwart, supervising electrical engineers in San Francisco.

Because of unexpected difficulties during excavation of the division dam—the first component of the plant built—the cost of the structure increased. Congress made an additional $60,000 available in 1917 to complete the plant; its generating capacity was also increased from 1,000 to 2,000 kilowatts. Beginning operations on 28 May 1918, the plant included the timber crib diversion dam spanning the Merced River about one mile below the Pohono Bridge at the intersection of State Highway 140 and the Big Oak Flat Road. The penstock, or conduit, that transports the water under pressure to the power plant, begins just past the intake and screens in the north abutment of the diversion dam. It consists of concrete, redwood stave, and riveted steel sections. The wooden portion, supported on wooden trestles, runs along the hillside north of the Merced, from the dam west to the powerhouse. Within the powerhouse, located about one mile west of the dam on the north bank of the Merced alongside Highway 140, two General Electric 1,000-kilowatt dynamos connected to two Pelton turbines. The Park Service dedicated the plant to Henry Floy, the New York electrical engineer whose voluntary study of the power problem and subsequent report and presentation of the project before the Congressional House Appropriations Committee resulted in the project’s successful conclusion. Sequoia National Park received the old electric plant above Happy Isles, which the park removed in 1919. During 1917-18 workers constructed three cottages to house operators at the new power plant. These still stand in The Cascades area and are used for employee housing.

Crews constructed the one-story frame ranger station at Aspen Valley on the Tioga Road in 1918, as well as the Gentry Ranger Station on the Big Oak Flat Road, and the Mariposa Grove and Chinquapin ranger stations. The park eliminated four of its early campgrounds between 1919 and 1925. The Mirror Lake road realignment. of 1919 resulted in abandonment of Camp 10; the Church Bowl took over the site of Camp 20 in 1920; the New Village post office rose on the site of Camp 18, which was eliminated in 1923; and the Ahwahnee Hotel was constructed on Camp 8 grounds in 1925-26.25

[25. Fitzsimmons, “Effect of the Automobile,” 106.]

2. A New Village Site Is Considered

Director Mather and other Park Service officials considered it essential to build a new administrative area in Yosemite Valley because of the rapidly growing volume of traffic in the summer. Commercial and service activities of the park still centered in the early village at this time. The increased tourist volume, however, was rapidly making that area obsolete. The necessity for all campers to register and receive camp assignments at park headquarters in the village resulted in heavy congestion on the main street. In addition, the administration building was too small to handle the large crowds and the village site as

|

Illustration 80.

Map of Yosemite Village. From Hall, Guide to Yosemite, 1920. |

[click to enlarge] |

| “At the U. S. National Park Service Administration Building are the offices of the Park Superintendent, Chief Ranger and other executive officers. In front of the building is a free information bureau with a park ranger in charge. Government maps and bulletins may here be obtained free or at a very nominal cost. Adjacent is a motorists’ information bureau maintained by the California State Automobile Association. At the left entrance is the telegraph and telephone office maintained by the government. The Yosemite Museum, which contains many excellent exhibits of the flora and fauna of the region is temporarily housed in this building.” |

Landscape Engineer Charles Punchard spent 7-1/2 months during 1918-19 in Yosemite, which Director Mather had chosen to be his showplace of the national park system. One of Punchard’s primary tasks involved locating a new village site, in addition to rearranging campgrounds and landscaping existing facilities. At the same time he studied landscape problems in other western parks. Punchard also began working on one of Mather’s pet projects, which involved providing a dormitory for the Yosemite rangers. The design of the completed Rangers’ Club pleased the director so much that he announced it would serve as a model for new construction in the park.

During this period Yosemite Valley became headquarters for the Park Service landscape program. Buildings erected beginning in 1921 to plans devised by this Landscape Engineering Division were the first examples of a new Park Service rustic style involving natural materials that harmonized with their particular environment. By late 1922 Landscape Engineer Daniel Hull, who had taken over after Punchard’s death, recommended to Mather that architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood be hired to develop ideas for the -new Yosemite administration and post office buildings. The Fine Arts Commission, however, rejected his designs as being inappropriate and too complex. Mather brought in another architect, Myron Hunt of Los Angeles, who developed an acceptable design for the administration building and also helped Hull and Mather complete a final plan for the valley redevelopment.26 The unified architectural design of the new administration center would feature battered stone veneers, shake siding and roofs, exposed logs, and hip roofs, long, horizontal lines would blend into the rock cliffs behind the village.

[26. William C. Tweed, “‘Parkitecture’: Rustic Architecture in the National Parks,” November 1978, draft, 133 pages, 29-32, 34, 39-40.]

The new Yosemite Village residential district was located among the trees and brush against the north valley cliffs. It consisted of curved streets and residences built to be environmentally harmonious with their environment. Punchard performed much of this early planning work. Part of the development called for moving three of the early army structures into the new group of residences and out of their intrusive locations in the meadow. An appropriation of $35,000 for construction of the new administration building and approval by the Post Office Department of plans for the construction, under a lease arrangement, of the new post office building started the relocation process.

3. The 1920s Period Involves a Variety of Construction Jobs

During the 1920-21 season, construction projects included four employees’ cottages, two auto sheds in the shops and barn group on the valley floor, a roadhouse and barn at Bridalveil Creek on the Glacier Point road, and a checking station at Gentry’s at the top of the grade on the Big Oak Flat Road. Activity during the 1921 fiscal year also produced a modern sewer system, preliminary improvements to the water system, additional sanitary provisions in the public camping grounds in the valley, and initial improvement of sanitary conditions in the camp in Tuolumne Meadows. In that same year Park Service Director Stephen Mather donated money for the Rangers’ Clubhouse—a personal gift to the officers and rangers of Yosemite—containing a large kitchen, dining room, lounge, and dormitory. To personalize the structure, each ranger with a record of two years of continuous service in Yosemite could nail a shoe from the hoof of his favorite horse on the lounge wall.

In 1923 the park erected ten comfort stations in the public campgrounds in a further effort to improve the sanitary situation. Similar work projected for fiscal years 1924 and 1925 would eliminate the serious sanitary situation that had prevailed in the public camps for the past several years. Additional structures built at this time included four more employees’ cottages in the valley and a frame bunkhouse at Chinquapin on the Wawona Road. After dam construction ended at Hetch Hetchy in 1923, the Park Service hoped to secure a barn, bunkhouse, mess house, and office located in the city of San Francisco’s construction camp. The city decided to retain its caretaker’s building and guest cottage, but turned the rest of the buildings over to the Park Service for their salvage value. Although the Yosemite Park and Curry Company proposed establishing a lunchroom and boat service at the dam, the city and Park Service ultimately agreed that the government would not encourage developments near the dam that might become a menace to the purity of the water supply. People would only be encouraged to visit and view the dam.

During the 1924 travel season crews began installing a ranger station, checking kiosk, and public comfort station at the foot of the Wawona grade in the Bridalveil area and started work on similar units at the Alder Creek station on the Wawona Road and at the El Capitan station at the foot of the Big Oak Flat grade. (Workers moved the old ranger residence at the El Capitan checking station to a new location and reconstructed i t.) Additional work included a ranger station and a small administrative headquarters—consisting of a comfort station, a house for the road maintenance crew, a mess house, a barn, and ranger living quarters—at Tuolumne Meadows on the Tioga Road. The ranger station was built to serve also as a contact station and entrance station into the park from Tioga Pass. It ceased to function as an entrance station with the construction in 1931 of a new one at the Tioga Pass summit several miles east, and its visitor contact function moved to a new building in 1936. It continued to serve as a ranger residence and office. Nine more comfort stations were added in 1924 in the public campgrounds. That same year construction began on a rough stone lookout station at Glacier Point, housing field glasses, to serve during the summer months as headquarters for a nature guide. This structure was an important aspect of the park’s new interpretive program and is discussed later in this chapter.

In November 1924 Director Mather presided over the dedication of the new administration building and the laying of cornerstones for the new museum, post office, and Pillsbury’s Pictures, Inc., Studio in the new Yosemite Village. This occasion marked the first step in the abandonment of the old village. The administrative, post office, and museum buildings, plus the Rangers’ Clubhouse would form the nucleus of the civic center, which would eventually include other studios and stores. After moving various units of the old village to the new site, the old buildings no longer needed, including the Sentinel Hotel, would be razed and the landscape restored.

In 1925 work crews completed a kiosk at Grouse Creek as part of a new checking station, and finished similar structures at Alder Creek and El Capitan. On 30 May 1925, the California Conference of Social Workers unveiled a tablet in memory of John Muir, marking the site of his sawmill and cabin. Earlier, on 19 May, a memorial plaque honoring Dr. Bunnell, member of the party that discovered the Yosemite Valley, had been placed on a large boulder in Bridalveil Meadow, a gift of the California Medical Association. Superintendent Lewis noted that this was the first time that any of the points of historic interest in the park had been permanently marked.27 Other work that year included relocation of the old ranger station at Tuolumne Meadows, constructing steps over the granite rock to the new Glacier Point lookout station, moving the ranger station structure from the Bridalveil checking station to a new location in the Lost Arrow residential group, and constructing a new four-room cottage from the material obtained from the wrecking of the old administration building. Also that year Director Mather decided to locate the ranger station on the El Portal road at Arch Rock, necessitating construction of a by-pass road on the north side of Arch Rock to accommodate outgoing traffic. J. W. Boysen started construction on a new studio in the New Village in 1925. [Editor’s note: the correct spelling is J. T. Boysen (Julius T. Boysen)—dea]

[27. W. B. Lewis, “General Statement,” in “Superintendent’s Annual Report,” 1925, n.p. (22?), in Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

Workers completed the new Arch Rock ranger station/residence in 1926. Construction during 1927 included moving the checking station at Arch Rock to the righthand side of the road for incoming cars, building an entrance gate at the park line on the Hetch Hetchy road, putting finishing touches on two new employee cottages in the valley, building the form work for a new detention building in the valley, establishing a ranger station and barn on the South Fork of the Merced River near Wawona, and constructing the Merced Lake patrol cabin to aid in snow surveys. In November of that year a fire in the stock room of Pillsbury’s auditorium destroyed the workrooms and theatre portion of the building along with two darkrooms and developing rooms.

In 1928 a change in the Arch Rock station general plan due to unexpectedly heavy traffic necessitated moving the two checking buildings from their location above the rangers’ living quarters to a site a short distance below the residence. A small building architecturally similar to them was moved from the El Capitan station and placed in the center of the Arch Rock group to facilitate the traffic flow.28 The park addressed the need for better housing for Yosemite schoolteachers by beginning construction of a suitable building on the school grounds at the end of 1928.

[28. John B. Wosky, Jr., Landscape Architect, to Thomas C. Vint, Chief Landscape Architect, 27 June 1928, in Box 28, YP&CCo. Architectural Reports, 1927-1939, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

Further development during the 1929 season involved a comfort station in the Glacier Point campground. One of the oldest Indians in Yosemite Valley, John Brown, had accomplished most of the stone masonry work on that structure. In Yosemite Valley, construction consisted of a new hospital building; an employee cottage; a women’s dormitory; two frost-proof toilet buildings in the newly established winter campground in the area now known as Sunnyside, or Camp 4; and remodeling of the superintendent’s residence, garage, and laundry. At the same time, a stone wall creating a pool at the outlet of a spring adjacent to the Merced Lake trail near Happy Isles, about where the Sierra Point trail intersected it, was nearing completion.

4. The New Hospital and Superintendent’s Residence

The building used as a hospital in Yosemite during the early Park Service years was the same facility that the War Department had used, slightly remodeled. It contained three rooms for patients, a small operating room, a nurse’s area, and a reception/consultation facility. The physician’s family used three other rooms as living quarters. Heavy tourist travel and the park’s distance from major hospital facilities increased the need for first-class service in the park. During the 1920-21 season a small addition to the hospital had made it possible to furnish better dental service.

By 1923 the park considered new hospital facilities absolutely essential because of increased visitation from all parts of the country, leading to the rapid spread of contagious diseases, and the unfamiliarity of most visitors with the rugged terrain of the park, resulting in many accidents. During the summer tents often had to be utilized for patient care, while other individuals ended up on the hospital porch. Many needy people often had to be turned away for lack of space.

In the 1928 Interior Department Appropriation Act, Congress granted money for the construction of a new hospital. The structure, dedicated in 1930 and later named for former park superintendent Washington B. Lewis, filled the long-felt need for modern medical, surgical, and dental facilities in the park. Located on the north side of the valley, halfway between the New Village and the Ahwahnee Hotel, the frame building, stone veneered below the first floor, had both a ward and

|

Illustration 81.

Lewis Memorial Hospital, Yosemite Valley. Photo by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984. |

[click to enlarge] |

|

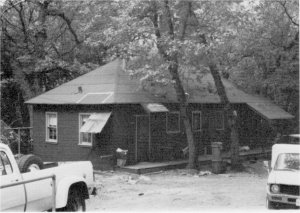

Illustration 82.

Paint shop in Yosemite Valley maintenance yard (former Indian Village residence). Photo by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984. |

[click to enlarge] |

The new superintendent’s residence, a two-story frame structure, was erected on the same site as the previous one. Workers basically tore down the earlier army structure, leaving only the framework of the dining room, kitchen, pantry, breakfast nook, one bedroom, and a bath, which were incorporated in the new house. The garage and laundry building had burned in the early summer and also had to be replaced. The new laundry unit was attached to the house. Work on this modern six-room structure ended in October 1929. The convertible women’s dormitory completed during the year was a four-room cottage.29

[29. Edward A. Nickel, Assoc. Structural Engineer, “Report on Building Construction, Season of 1929,” 8 February 1930, in Central Files, RG 79, NA.]

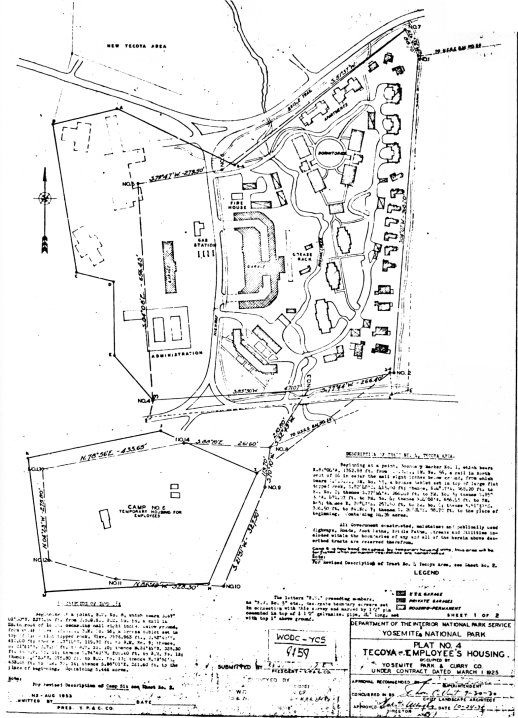

5. The Indian Village in Yosemite Valley

During 1929 Superintendent Charles G. Thomson took a census of the inhabitants of the old Indian village, located in the area now occupied by the Yosemite Medical Group (former Lewis Memorial Hospital). He found sixty-seven Indians living there in makeshift dwellings formed from ragged tents, old boxes, and other cast-off materials. Although these residents possessed no formal rights to a reservation and had no legal rights entitling them to reside in the valley, the Department of the Interior and the superintendent agreed that those who had been born in the valley and could trace their ancestry to either the Miwok or Mono Paiute Indians had a moral right to continue living there. The village had to be moved to another location, however, because of the impending construction of the new hospital on that site. Superintendent Thomson also considered the old village too unsightly and unhealthy to remain.

Accordingly Thomson selected a new village site about one-half mile west of Yosemite Lodge. The superintendent assigned the small, three-room cabins to selected Indians, under special use permits, who rented them at a nominal monthly fee. Only those Indians living in Yosemite in 1929 who could trace their ancestry to early inhabitants of the area were considered for housing. Furthermore, government policy dictated that quarters be assigned only to the man as head of the family or to a woman whose husband had died or left her. If a woman remarried, she lost the right to live in the new village and was obligated to move unless her new husband had a moral right to reside there. The moral right was passed on to the first male child in each family. Relatives and other Indians from outside the valley could not reside in the new village for long periods. The Park Service considered supervision of the community life of the Indians one of its administrative responsibilities.30

[30. Harold E. Perry, “The Yosemite Indian Story: A Drama of Chief Tenaya’s People,” 1949, typescript, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center, 6-8.]

6. More Construction and Removal of Some Older Structures

Building construction, repair, and relocation during the 1930 season included, in Yosemite Valley, erection of a four-family employees’ residence and a staff residence as well as replacement of the wooden trestles on the hydroelectric pipeline. A new raised platform in Camp 15 provided a stage for the public entertainment presented each weeknight during the summer.