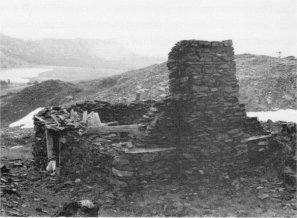

Rock wall cribbing and old roadbed of Coulterville Road (on USFS land), view to east.

Photo by Robert C. Pavlik, 1984.

[click to enlarge]

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Resources > Chapter II: Yosemite Valley as a State Grant and Establishment of Yosemite National Park, 1864-1890 >

Next: 3: Cavalry 1890-1905 • Contents • Previous: 1: Early History

A. Interest Mounts Toward Preserving the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove 51

1. Yosemite Act of 1864 51B. State Management of the Yosemite Grant 65a. Steps Leading to the Preservation of Yosemite Valley 51

b) Frederick Olmsted‘s Treatise on Parks 55

c) Significance of the Yosemite Grant 59

1. Land Surveys 65

2. Immediate Problems Facing the State 66

3. Settlers‘ Claims 69

4. Trails 77a) Early Survey Work 775. Improvement of Trails 89

b) Routes To and Around Yosemite Valley 78

c) Tourist Trails in the Valley 79(1) Four-Mile Trail to Glacier Point 80

(2) Indian Canyon Trail 82

(3) Yosemite Fall and Eagle Peak Trail 83

(4) Rim Trail, Pohono Trail 83

(5) Clouds Rest and Half (South) Dome Trails 84

(6) Vernal Fall and Mist Trails 85

(7) Snow Trail 87

(8) Anderson Trail 88

(9) Panorama Trail 88

(10) Ledge Trail 89a) Hardships Attending Travel to Yosemite Valley 896. Development of Concession Operations 114

b) Yosemite Commissioners Encourage Road Construction 91

c) Work Begins on the Big Oak Flat and Coulterville Roads 92

d) Improved Roads and Railroad Service increase Visitation 94

e) The Coulterville Road Reaches the Valley floor 951) A New Transportation Era Begins 95f) The Big Oak Flat Road Reaches the Valley Floor 100

2) Later History 99

g) Antagonism Between Road Companies increases 103

h) The Wawona Road Reaches the Valley floor 106

i) Roads with in the Reservation boundary 110a) Hotels and Recreational Establishments 1147. Schools 159(1) Upper Hotel 115b) Stores, Studios, and Other Services 145

(2) Lower Hotel/Black‘s Hotel 122

(3) Leidig‘s Hotel 122

(4) Mountain View House 123

(5) Wawona Hotel 126

(6) La Casa Nevada 133

(7) Cosmopolitan Bathhouse and Saloon 135

(8) Mountain House 138

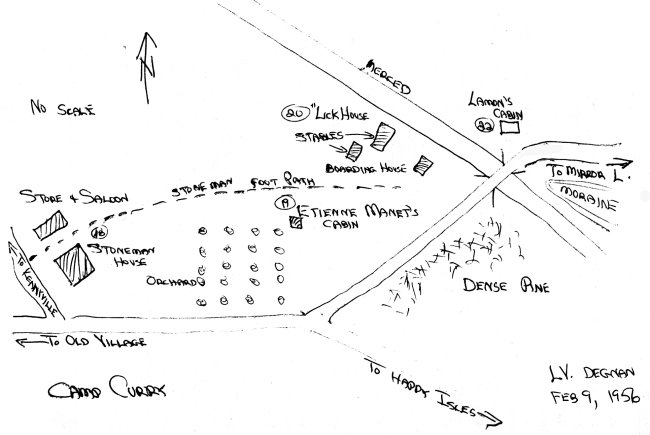

(9) Stoneman House 139(1) Harris Campground 145c) Transportation in the Valley 154

(2) Degnan Bakery 146

(3) Fiske Studio 147

(4) Bolton and Westfall Butcher shop 147

(5) Flores Laundry 148

(6) Cavagnaro Store 148 (7) Stables 148

(8) Sinning Woodworking shop 148

(9) Stegman Seed Store 149

(10) Reilly Picture Gallery 149

(11) Wells Fargo office 150

(12) Folsom bridge and Ferry 151

(13) Chapel 151

d) Staging and Hauling to Yosemite Valley 155

8. Private Lands 164a) Bronson Meadows (Hodgdon Meadow) area 1679. The Tioga Mine and Great Sierra Wagon Road 243(1) Crocker station 167b) Ackerson Meadow 171

(2) Hodgdon ranch 167

c) Carlon or Carl Inn 171

d) Hazel Green 171

e) Crane Flat 174

f) Gin Flat 175

g) Tamarack Flat 176

h) Foresta/Big Meadow 177(1) McCauley barn 180i) Gentry station 188

(2) Meyer barn No. 1 (Saltbox) 181

(3) Meyer barn No. 2 (Cribwork interior) 181

(4) Big Meadow Cemetery 181

j) Aspen Valley 189(1) Hodgdon cabin 189k) Hetch Hetchy Valley/Lake Eleanor area 192

(2) East Meadow Cache 192(1) Miguel Meadow cabin 193l) White Wolf 198

(2) Kibbe cabin 196

(3) Elwell cabins 196

(4) Tiltill Mountain 197

(5) Lake Vernon cabin 197

(6) Rancheria Mountain cabin 197

(7) Smith Meadow cabin 198

m) Soda Springs and Tuolumne Meadows 199(1) Lembert cabin 201n) Tioga pass 207

(2) Tuolumne Meadows cabin 206

(3) Murphy cabin 206

(4) Snow Flat cabin 207(1) Dana fork cabin 207o) Little Yosemite Valley 210

(2) Mono pass cabins 210(1) Washburn/Leonard cabin 210p) Yosemite Valley 211(1) Pioneer Cemetery 211q) Glacier Point 232(a) White Graves 212(2) Lamon cabin 222

(b) Indian Graves 218

(3) Hutchings cabin 222

(4) Muir cabin 224

(5) Leidig cabin and barn 225

(6) Howard cabin 226

(7) Happy Isles cabin 227

(8) Clark cabin 227

(9) Four-Mile Trail cabin 228

(10) Mail Carrier Shelter cabins 228

(11) Stegman cabin 228

(12) Hamilton cabin 228

(13) Shepperd cabin 229

(14) Manette cabin 229

(15) Whorton cabin 229

(16) Boston cabin 229(1) McGurk cabin 232r) Wawona 234

(2) Mono Meadow cabin 233

(3) Ostrander cabin 233

(4) Westfall Meadows cabin 234(1) Pioneer Cemetery 234s) El Portal area 242

(2) Crescent Meadows cabin 235

(3) Turner Meadow cabin 235

(4) Buck Camp 235

(5) Mariposa Grove cabins 236

(6) Chilnualna Fall 237

(7) Galen Clark Homestead Historic site 237

(8) Cunningham cabin 240

(9) West Woods (Eleven-Mile station) 240

(10) Other Homesteaders 241(1) Hennessey ranch 242

(2) Rutherford Mine 243a) Early activity in the Tuolumne Meadows area 24310. Management of the Grant by the Yosemite Commissioners 258

b) Formation of the Tioga Mining district 244

c) The Great Sierra Consolidated Silver Company Commences Operations 246

d) Construction of the Great Sierra Wagon Road 250

e) The Tioga Mine Plays Out 256a) Replacement of the Board of Commissioners, 1880 25811. Establishment of Yosemite National Park 289

b) Report of the State Engineer, 1881 259(1) Protecting Yosemite Valley from Defacement 260c) Remarks on Hall‘s Report 268(a) Preservation of the Water shed 260(2) Promoting Tourism 262

(b) Regulation of Use of the Valley Floor 261

(c) Treatment of the Valley Streams 262(a) Improving Approaches to the Valley 263(3) Lands caping 266

(b) Improvements to Travel In and About Yosemite Valley 263

(c) Trails 264

(d) Footpaths 264

(e) Bridges 265

(f) Drainage and Guard Walls 265

(g) Hotels, Stores, Houses 266

(4) Agricultural Development 267

(5) River overflow 267(1) Yosemite Valley River Drainage and Erosion Control 269(2) Yosemite Valley Vegetative Changes 273d) Report of the Commissioners, 1885-86 279(a) Fire Suppression 273(3) Mariposa Grove Management Problems 277

(b) Drainage of Meadows 276

(c) Introduction of Exotics 277

e) Report of the Commissioners, 1887-88 282

f) Report of the Commissioners, 1889-90 288a) Accusations of Mismanagement of the State Grant 289

b) Arrival of John Muir in California 296

c) John Muir and Robert Underwood Johnson Join forces 298

d) Response of the Commissioners to Charges of Mismanagement 300

e) Comments on the Controversy 301

f) The Yosemite National Park Bill Passes Congress 304

g) Comments on the Preservation Movement and Establishment of Yosemite National Park 305

Mariposa Grove

1. Yosemite Act of 1864

a) Steps Leading to the Preservation of Yosemite Valley

The widespread publicity on Yosemite Valley, coupled with a nascent thrust toward scenic preservation, prompted a few respected far-seeing California residents to push for passage of a law to protect Yosemite’s outstanding features for all time. The conviction that man was destined to use and unreservedly exploit the country’s wilderness prevailed by the mid-1850s. The westward-moving pioneers had ruthlessly conquered both the Indian populations they met and the land acquired from their dispossession. As farms and towns appeared, settlers overplowered fields, overgrazed grasslands, ravaged forests for building materials and firewood, and exterminated wildlife for food and profit. It was then that a countermovement began, spearheaded by such respected authors as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, and by important painters such as George Catlin, who saw the need to preserve some of America’s landscapes. The discovery of Yosemite Valley provided the first believable evidence that the United States had a valid claim to cultural recognition through scenic wonders. Yosemite became the object of scenic nationalism and was popularized as such in the press of the time.

At the same time, during the 1850s and 1860s, many in California lamented the loss of rare giant trees to lumber interests, of alpine meadows to sheepmen, and the misuse of lands in Yosemite Valley for commercial exploitation and economic gain. Foremost among those individuals were Starr King, who became one of the leaders in the effort to save Yosemite Valley; Judge Stephen Field, who early visualized the site’s need for a geological survey and who had much to do with its accomplishment by Josiah Dwight Whitney, assisted by William H. Brewer and Clarence King; Frederick Law Olmsted, regarded as the founder of landscape architecture in America, who had designed Central Park in New York City—a revolutionary attempt to develop a natural landscape in the heart of a large city. Immediately after his arrival in California in September 1863 to manage the famed Mariposa Estate grant formerly owned by John Charles Fremont, Olmsted became enthusiastic about Yosemite Valley and worked tirelessly for its conservation; Jessie Benton Fremont, wife of John; Israel W. Raymond, one of the most active workers on the Yosemite park proposal; Dr. John F. Morse, a San Francisco physician; Josiah D. Whitney, California’s state geologist; and William Ashburner of the Whitney survey party.

Those individuals were astute and practical enough to realize that political action was required to permanently save the natural wonders of Yosemite from destruction. Israel Raymond, the California representative of the Central American Steamship Transit Company of New York, addressed a letter to California’s junior senator John Conness, urging him to present a bill to Congress on the preservation of Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove. That important missive of 20 February 1864 stated: “I think it important to obtain the proprietorship soon, to prevent occupation and especially to preserve the trees in the valley from destruction. . .”1 Conness in turn sent a letter to the Commissioner of the General Land Office, J. W. Edmonds, in March requesting that he prepare the final draft of the bill and send it on using Raymond’s language and boundary descriptions of Yosemite and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove. In introducing the bill on 28 March 1864, Conness made it clear that the bill had come to him from various gentlemen in California of taste and refinement and that the General Land Office also favored it.

[1. Huth, “Yosemite: The Story of an Idea,” 29.]

Aiding passage of the proposal were memories of an unfortunate incident in 1852 that had greatly advanced the idea of preservation of the giant sequoias—the stripping of one-third of the bark of one of the trees in the Calaveras Grove of Big Trees by two businessmen, who shipped it East for display and then put it on exhibition in London in 1854. That act of vandalism created furor in California/ especially when the tree began to decay, and aroused an overpowering preservationist sentiment in both the East and the West that forced people to ponder their responsibilities in regard to the protection of nature. The publicity accorded the sacrifice of that tree advanced the idea of conservation of giant sequoias by making their plight known.

On 30 June 1864, Congress passed an act segregating for preservation and recreational purposes the

“Cleft” or “Gorge” in the Granite Peak of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, situated in the county of Mariposa . . . and the head-waters of the Merced River, and known as the Yosemite Valley, with its branches and spurs, in estimated length fifteen miles, and in average width one mile back from the main edge of the precipice, on each side of the Valley, with the stipulation, nevertheless, that the said State shall accept this grant upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public usú, resort, and recreation; shall be inalienable for all time. . . .2

[2. The Yosemite Guide-Book (Cambridge, Mass.: University Press, 1870), 2. Conness further stated in the Senate hearing that the grant areas

are for all public purposes worthless, but . . . constitute, perhaps, some of the greatest wonders of the world. The object and purpose is to make a grant to the State, on the stipulations contained in the bill, that the property shall be inalienable forever, and preserved and improved as a place of public resort. . . .

Ibid. According to the Yosemite Valley commissioners, the area’s governing body, although the Yosemite Grant covered fifty-six square miles, only about three percent of the tract could be made useful for any other purpose than that to which the act of Congress devoted it—namely, as a place for public resort and recreation. The section of the grant along the foot of the bluffs was either too high, very rocky, or covered with such a thick growth of heavy timber that it was rendered “entirely unfit for purposes of cultivation.” On the valley floor, only 745 acres were meadowlands, while the rest were fern lands requiring clearing and cultivation before they could be farmed. Obviously, agricultural pursuits were being considered from the beginning. Biennial Report of the Commissioners to Manage the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa _Big Tree Grove For the Years 1887-88 (Sacramento: State Printing Office, 1888), 8.]

The Yosemite Grant included 36,111 acres and was entrusted to the state of California with certain stipulations. The act also granted, under similar conditions, four sections of public land, or 2,500 acres, containing the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees (see Appendix D). The grove was included in the grant to protect it from logging and other commercial exploitation. The purpose of the grant, as indicated by the stringent boundaries that ignored the ecological framework of the region, was to preserve monumental scenic qualities rather than an ecosystem. Although the words “national park” were not used in the legislation, in effect the Yosemite Grant embodied that concept, although neither Congress nor the federal government accepted any responsibility for the valley’s preservation or improvement. The act clearly stipulated that the valley and grove were to be managed by the governor of California and eight commissioners appointed by him and serving without pay, although the state would fund their traveling expenses. On 28 September 1864, Gov. Frederick F. Low of California proclaimed the grant to the state, and, in accordance with the act’s stipulations, appointed eight commissioners to manage the area: Frederick Law Olmsted, J. D. Whitney, William Ashburner, I. W. Raymond, E. S. Holden, Alexander Deering, George W. Coulter, and Galen Clark.

As chairman of the first board of commissioners to manage Yosemite Valley and the Big Tree Grove, Olmsted took the lead in efforts to organize management of the grant. Because he established a permanent camp in the valley and directed protection of the area prior to the state’s formal acceptance of the grant, he has been referred to as its first administrative officer. The commissioners agreed to hire one of their number as an on-the-scene employee, or Guardian, of the grant. Galen Clark initially served in that capacity, from 1866 to 1880. (See Appendix E for a list of the state Guardians of Yosemite Valley.) The Guardian’s duties were to patrol the grant and prevent depredations; build roads, trails, and bridges; bestow and regulate leases for the erection of hotels and other improvements; use the incomes from those leases to preserve and improve the valley; and serve as the commission’s liaison with the residents of the valley. The commissioners believed that the Guardian and/or a sub-Guardian should always be present in or about the valley and Big Tree Grove, at least during the visitor season, and that they should have police authority to arrest offenders on the spot.3

[3. Biennial Report of the Commissioners to Manage the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove, For the Years 1866-7 (San Francisco: Towne and Bacon, 1868), 7. Ultimately the lack of authority in the Guardian position led to the continuance of activities detrminental to the welfare of the valley and grove.]

b) Frederick Olmsted’s Treatise on Parks

At this point, note should be taken of an important document authored by Frederick Law Olmsted in response to a request by the Board of Yosemite Commissioners. That body asked Olmsted to prepare a report for the California legislature defining the policy that should govern management of the grant and making recommendations for its implementation.

Throughout 1865 Olmsted worked on this statement in which he presented a set of reasons for the establishment of parks and a detailed plan of management for Yosemite Valley in particular. The plan conformed with his belief that Congress, by setting aside this area, had recognized the ideal of free enjoyment of scenic areas by all classes of people and the state’s duty to preserve Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove for that purpose forever. This document, finished in August 1865, never received widespread exposure or the critical acclaim due it. Its significance lies in its philosophical arguments for the creation of state and national parks, in the sweeping scope of its political and moral justifications for establishing pleasure grounds for the masses.

Olmsted believed two factors had influenced Congress to set aside the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove. One, interestingly enough, in terms of the “worthless lands” theory of park establishment, involved Congress’s belief that a direct pecuniary advantage would accrue to the country in terms of tourist dollars as the valley became more accessible. 4 Olmsted regarded this as only an incidental factor in establishment of the grant, however.

[4. Frederick Law Olmsted, “The Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Trees: A Preliminary Report,” 1865, with an introductory note by Laura Wood Roper, repr. from Landscape Architecture 43, no. 1 (October 1952): 17.]

More importantly, he felt the government recognized a duty to protect its citizens in their pursuit of happiness against any obstacle presented by the actions of selfish individuals, such as the aggrandizement of land for personal gain:

It is a scientific fact that the occasional contemplation of natural scenes of an impressive character, particularly if this contemplation occurs in connection with relief from ordinary cares, change of air and change of habits, is favorable to the health and vigor of men and especially to the health and vigor of their intellect beyond any other conditions which can be offered them, that it not only gives pleasure for the time being but increases the subsequent capacity for happiness and the means of securing happiness. . . .

If we analyze the operation of scenes of beauty upon the mind, and consider the intimate relation of the mind upon the nervous system and the whole physical economy, the action and reaction which constantly occur between bodily and mental conditions, the reinvigoration which results from such scenes is readily comprehended. Few persons can see such scenery as that of the Yosemite, and not be impressed by it in some slight degree. . . .5

[5. Ibid., 17, 20.]

Olmstead noted that although the rich could afford to provide recreational opportunities for themselves, the government had to provide them for others, often by withholding scenic places from the grasp of individuals and opening them to all persons for recreation of the mind and body: “The establishment by government of great public grounds for the free enjoyment of the people under certain circumstances, is thus justified and enforced as a political duty.6 The Yosemite legislation had been enacted, Olmsted perceived, in realization of the fact that the humble masses could appreciate beauty and art as much as the privileged classes did.[6. Ibid., 21]

Olmsted believed the main duty of the commissioners entailed enabling the masses to benefit from the major attribute for which the valley and grove had been set aside—their natural scenery:

The first point to be kept in mind then is the preservation and maintenance as exactly as is possible of the natural scenery; the restriction, that is to say, within the narrowest limits consistent with the necessary accommodation of visitors, of all artificial constructions and the prevention of all constructions markedly inharmonious with the scenery or which would unnecessarily obscure, distort or detract from the dignity of the scenery.7

[7. Ibid., 22]

Olmsted warned the state to use care to protect the values of the area as a museum of natural science and not permit the sacrifice of anything of value to future visitors:

. . . it is important that it should be remembered that in permitting the sacrifice of anything that would be of the slightest value to future visitors to the convenience, bad taste, playfulness, carelessness, or wanton destructiveness of present visitors, we probably yield in each case the interest of uncounted millions to the selfishness of a few individuals. . . .

An injury to the scenery so slight that it may be unheeded by any visitor now, will be one of deplorable magnitude when its effect upon each visitor’s enjoyment is multiplied by these millions. But again, the slight harm which the few hundred visitors of this year might do, if no care were taken to prevent it, would not be slight if it should be repeated by millions.8

[8. Ibid.]

Olmsted recommended laws to prevent the unjust use of this public property, to prevent carelessness of the rights of posterity as well as of contemporary visitors. In addition to its preservation duty, the state had an obligation to make the park accessible to the masses, including provision of transportation facilities, camping accommodations, and a good access road to the park to shorten the trip and lessen its cost. Such a road would also enable bringing in supplies and provisions so that trees would not have to be cut down in the grant or the valley floor farmed.

Olmsted noted that the commission also proposed a road to and around the Mariposa Grove as a fire barrier, a road around the valley floor with turnouts, footpaths from that trail to outstanding scenic points, and construction of five cabins in the valley to be used as free resting places for visitors and to rent camp equipment and sell provisions. Finally Olmsted recommended that because of the beautiful scenery, natural scientists and artists be represented on the board of commissioners.

It is unfortunate that Olmsted’s views did not gain a wider audience in the state legislature and elsewhere. Certainly if his recommendations had been followed, at least some of the later problems in park administration might have been avoided and the park values have suffered less. Obviously Olmsted was philosophically years ahead of his time and voiced thoughts whose significance the majority of people were as yet unable to comprehend.

The California legislature met every two years, and that of 1864 had already adjourned when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant into law. Therefore not until 2 April 1866 did the state legislature pass an act accepting the grant from Congress, confirming the appointment of the commissioners, and conferring on that body full power to manage and administer the trust by making all rules, regulations, and by-laws for the government, improvement, and preservation of the area. The act also contained provisions making it a penal offense to commit injurious acts on the premises and other sections relative to further survey work, while appropriating $2,000 for carrying out the above actions.

c. Significance of the Yosemite Grant

At the time the legislation setting aside the Yosemite Grant passed Congress, it caused little stir across the nation, despite the fact that it set an important national precedent. It constituted the first instance of a central government anywhere in the world preserving an area strictly for a nonutilitarian purpose—the protection of scenic values for the enjoyment of the people as a whole:

This was not an ordinary gift of land, to be sold and the proceeds used as desired; but a trust imposed on the State, of the nature of a sotemn compact, forever binding after having been once accepted.9

[9. Quoted by Douglass Hubbard, “Olmsted - Prophet,” in Yosemite, Saga of a Century: 1864-1964 (Oakhurst, Calif.: The Sierra Star Press, 1964), 9.]

Additionally, many have expressed their belief that the Yosemite Grant marked the beginning of the national park movement in America and in the world and should be regarded as the first unit of the later National Park System. Finally, the Yosemite act constituted the first establishment of a state park and was thus the beginning not only of the California State Park System but of state parks nationwide.10

[10. Frederick A. Meyer, “Yosemite - The First State Park,” in Yosemite, Saga of a Century, 16. To bolster the argument that Yosemite was the point of departure from which a new theory of conservation evolved, the following quotations are presented that predate the establishment of Yosemite National Park:

Most fittingly has Congress set the Yosemite apart from the public domain, and consecrated it to mankind, as a National Park and pleasure-ground forever, (p. 458)

. . . the Mariposa Grove being also included in the Congressional grant which set aside the Yosemite as a National Park. . . . (p. 462)

From notes made on a trip in May 1867 by Gen. James F. Riesling, Across America, 1874. And,

. . . the Yosemite Valley is a unique and wonderful locality: it is an exceptional creation, and as such has been exceptionally provided for jointly by the Nation and State - it has been made a National public park and placed under the charge of the State of California, (p. 22)

This, the first application in print of the term “national park” in reference to Yosemite, is from J. D. Whitney, The Yosemite Book, 1868. Memorandum, Granville B. Liles, Actg. Supt., Yosemite National Park, to Regional Director, Western Region, NPS, 7 November 1963.]

In 1864 George P. Marsh published Man and Nature, the first treatise to approach the theme of conservation in a scholarly fashion. A widely read author, Marsh’s ideas probably influenced the men responsible for the Yosemite Grant. As early as 1865 a group of dignitaries from the East Coast, representing the nation’s press, visited the new Yosemite state park as guests of Mr. Olmstead. Among those important people were Schuyler Colfax, speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives; Samuel Bowles, editor of the Springfield (Mass.) Republican; Charles Allen, the attorney-general of Massachusetts; and Albert D. Richardson, war correspondent of the New York Tribune. In a travel account published later, Bowles stated that

This wise cession and dedication [of the Yosemite Valley] by Congress, and proposed improvement by California . . . furnishes an admirable example for other objects of natural curiosity and popular interest all over the Union. New York should preserve for popular use both Niagara Falls and its neighborhood and a generous section of her famous Adirondacks, and Maine one of her lakes and its surrounding woods.11

[11. Samuel Bowles, Across the Continent (Springfield, Mass.: Samuel Bowles & Company, 1865), 231. - Albert Richardson referred to Yosemite as “A Grand National Summer Resort” in Beyond the Mississippi, published in 1867 but based on his trip to the valley two years earlier, quoted in William R. Jones, “Our First National Park: Yellowstone? . . . or Yosemite?” Audubon Magazine 67, no. 6 (November-December 1965): 383-84.]

The national scope, permanence, and importance to future generations attributed to the Yosemite grant were also apparent in a Saturday. Evening Post editorial in 1868:

The Great American Park of the Yosemite. With the early completion of the Pacific Railway there can be no doubt that the Park established by the recent Act of Congress as a place of free recreation is for? all the people of the United States and their guests forever.12

[12. New York Evening Post, quoted in Sacramento (Calif.) Daily Union, 29 July 1868, 3.]

The preceding statements indicate that from the beginning the true significance of the Yosemite Grant was perceived as being not simply preservation of one particular local scenic area, but the possible initial step in a precedent-setting systematic approach to a national program of preservation of areas of unique scenic interest, beauty, and curiosity. It became the first official recognition that man should not always subjugate nature, but also enjoy it recreationally and aesthetically, and that the government’s role was to preserve areas for that purpose.

The Yosemite Grant was not the product of a nascent public concern for ecological values of the environment. Preservation of scenery and natural curiosities for public enjoyment dictated its establishment, not its biological attributes. Few in America yet understood watershed functions, forestry principles, or the basic interrelationship between plants, animals, and man.

The Yosemite Grant constituted possibly the initial major manifestation of a growing American concern with the loss of its wilderness and its pioneer values. The Yosemite Grant tied in with an early reaction to despoliation and avarice and a fear of the private appropriation of large tracts of land in the public domain.13 By the late 1860s and early 1870s, the American public began experiencing a variety of emotions as a result of fundamental changes in society during and after the Civil War. A period of romantic idealism expressed nostalgia for a dwindling frontier experience. At the same time, Americans felt alarm at the rising tide of materialism, which would increase during the period of the Industrial Revolution. That repugnance fostered and strengthened an emotional reaction—a spiritual attachment to Nature and its basic, simpler values. Feelings of inadequacy in terms of cultural background as compared to the great European civilizations led to a fascination with monumentalism. Celebrating the scenic grandeur of America’s West became a way of competing successfully with European culture and traditions. Yosemite Valley certainly was regarded by its early visitors as a nationalistic resource, an outstanding example of America’s worth in the eyes of the world.

[13. Joseph L. Sax, Mountains Without Handrails: Reflections on the National Parks (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1980), 8.]

One of the prerequisites of Congress’s acceptance of early national parks would be that they have little economic value and thus be worthless for anything other than pleasuring grounds. Early preservationists found that resistance to the establishment of public scenic areas could be offset if they were touted as so remote as to be economically worthless to the country. Legislators continued to feel for many years in regard to the establishment of new park areas that valuable commercial resources should be either excluded at the outset or opened to exploitation regardless of their location.14 Proponents of the Yosemite Grant assured Congress that the valley would be worthless for mining, logging, grazing, or agricultural interests. It is interesting, however, that the state intended from the beginning to make money from the area, through lease arrangements, which could be reinvested in park development. The valley also was a money-making proposition for settlers who sold provisions and provided accommodations to tourists. Through the years the valley has proven a lucrative source of money from tourism and commercial recreation activities. It was actually the potential value of the valley and the Mariposa Grove in terms of commercial tourism and logging activities that many backers of the grant feared would lead to its exploitation and eventual destruction.

The wording of the legislation and comments by visitors and writers of the time are sufficient proof that the object of the grant was to preserve a scenically outstanding area of nationwide value, to establish a true national park, even though it was a park to be managed by a state government. The fact is that in 1864 the federal government was far less diversified than now and no one yet envisaged all-encompassing federal legislation to conserve state areas for national park purposes. In addition, the country’s leaders were much too involved in the problems and strategies of the Civil War to ponder the philosophical implications of what they were doing for the nation at large. President Lincoln himself probably had little inkling of the impact of his signature on the bill setting aside Yosemite Valley as a park. Other matters were occupying his thoughts: an attempt within the Republican party to unseat him as president; Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s repulse at Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia; and Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s investment of Petersburg, the key to Richmond, Virginia. It is easy to see how

The Yosemite Act was lost in the tides of war, and only in recent years has its monumental significance been evaluated by historians. It is clear now that the reservation of Yosemite marked perhaps the most significant single event in the changing relationship of Americans to the land they live on.15

[14. Alfred Runte, National Parks: The American Experience (Lincoln University of Nebraska Press, 1979), 48.]

[15. Harold Gilliam, “Centennial of a Pioneer’s Dream,” San Francisco Chronicle, 28 June 1964.]

Despite the fact that Yellowstone was the first federal venture in the field of preservation, it did not advance the concept of conservation in the first years of its existence. Yosemite, on the other hand, began growing and developing as soon as it was set aside, and became a proving ground for new ideas in conservation and park management. Olmsted quickly formulated plans for the best management of the park, and the California legislature voted appropriations for improvements as soon as possible. The early establishment of Yosemite Valley as a park unit under state control significantly influenced the later development of both the National Park System, the California State Park System, and state park systems nationwide, which all benefitted from the experience and knowledge of park principles and management gained in those early Yosemite years. Olmsted’s penetrating analyses of park problems and opportunities were strongly influenced by his Yosemite experience, and his reports are the origin of much of the best of today’s park principles.16

[16. Meyer, “Yosemite - The First State Park,” in Yosemite, Saga of a Century, 17.]

Carl P. Russell stated that it was apparent that the original proponents of the Yosemite act—the scientists, educators, and journalists who visited and described Yosemite and the congressmen and senators who envisioned the initial concept and formulated the legislation—thought of the Yosemite Grant as more than the first state park. They also perceived it as the first official embodiment of the concept that there are places of beauty and of scientific interest that should not be appropriated by individuals or private interests. This was the birth of the National Park idea.17 And it should be noted that when the National Park System was extended in 1890, it was to protect additional areas in California, around Yosemite as well as the present Sequoia National Park and General Grant Grove—areas in a state where the concept of national and local parks was developing in a thoughtful way.

[17. Carl P. Russell, “Birth of the National Park Idea,” in ibid., 7.]

1. Land Surveys

The state legislature had created the California Geological Survey in 1860 and appointed Josiah Whitney, one of the most respected geologists in America, as its head. Whitney was instructed to make a complete geological survey of the state and submit a report of his findings containing maps and diagrams, scientific descriptions of geological and botanical discoveries, and specimens of same.

As soon as the state of California accepted the Yosemite Grant, it determined to obtain certain statistical data. Land surveys, necessary to establish the boundaries of the grants, were made in the fall of 1864 by Clarence King and James T. Gardner, appointed U. S. deputy surveyor for that purpose. (Gardner later changed the spelling of his name to Gardiner.) Their notes were filed in the office of the U. S. surveyor general of California, who forwarded the official plat of the grant to Washington and to the commissioner of the General Land Office. Gardner also drew a map of the Yosemite Valley, showing the grant boundaries and the topography of its immediate vicinity.

The legislative act accepting the grant also authorized the state geologist to further explore the grant and the adjacent Sierra Nevada in order to prepare a full description of the country with maps and illustrations, to be published and sold to prospective visitors. In 1865 a party consisting of King, Gardner, H. N. Bolander, and C. R. Brinley set out to make a detailed geographical and geological survey of the High Sierra adjacent to Yosemite Valley. Another geological survey party under Charles F. Hoffmann continued additional surveys during 1866.

Two editions of the Yosemite survey work originally published in the state geological survey publication Geology in 1865 were planned for publication, both with text, maps, and illustrations, but only one with photographs. It would be called The Yosemite Book (1868), the other the Yosemite Guide-book (1869). The text was a thorough guide to the valley and surrounding mountains, while the accompanying map was acclaimed as the first accurate map of a high mountain region prepared in the United States. Carleton E. Watkins’s photographic illustrations complemented the text. The book greatly increased visitation to the valley by providing information necessary to travelers. Hoffman and his party also surveyed the valley floor and plotted on a map the number of acres in each tract of meadow, timber, and fern land and the boundaries of individual settlers’s claims and the number of acres each had enclosed. They also surveyed the Big Tree Grove, and measured, plotted, and numbered the largest trees.18

[18. Report of the Commissioners to Manage the Yosemite Valley . . . . For the Years 1866-7, 3-6.]

2. Immediate Problems Facing the State

Yosemite Valley’s reputation as one of the most scenic wonders of the world continued to grow. The long, tiring stage or horseback trip; the expense of hiring horses, guides, and packers; and the exorbitant charges demanded by hotelkeepers, however, limited the number of visitors.

Access to the valley was one of the main problems addressed after establishment of the grant. From the north, travelers on horseback usually took the seventeen-mile wagon road from Coulterville to Black’s Hotel at Bull Creek, where they stayed overnight, covering the thirty-two miles into Yosemite Valley the next day. These travelers had to pay to cross the Merced River on Ira Folsom’s ferry, three-fourths of a mile below the Lower Hotel. The only alternative was to follow an unsatisfactory trail farther up the valley on the north side and cross the Merced over a log bridge Hutchings had erected prior to 1865 opposite his hotel, between Yosemite Fall and Sentinel Rock, replacing the crude log structure Hite built in 1859. In order to improve this situation, the Yosemite commissioners prior to 1866-67 erected a good saddle horse bridge across the Merced at the foot of Bridalveil Meadow, near where the trail from the north entered the valley. This Lower Iron Bridge (later Pohono Bridge) enabled visitors to make a full circuit tour of the valley if desired, without the delay and expense of the ferry ride.

The commissioners did not consider it their duty to improve the approaches to the valley, much to the disappointment of neighboring counties. They decided rather that this should be left to competition between the counties, towns, and individuals interested in securing that travel business. The commissioners slightly improved the trail from Yosemite Valley up the Merced Canyon to Vernal Fall so that visitors could ride nearly to its foot. They also placed a bridge across the river above Vernal Fall, facilitating the trip to the top of Nevada Fall. They proposed soon to place a convenient staircase near the ladders at Vernal Fall to make the ascent easier and less dangerous. In the valley the commissioners intended to increase accessibility to all points of interest; remove all obstacles to free circulation, such as trail charges; improve the road around the valley floor; and build a bridge over Ililouette Creek. They considered bridges across the Merced at the upper end of the valley and across Tenaya Creek imperative.19

[19. Ibid., 11, 13.]

High water in the winter of 1867-68 swept away all bridges across the Merced River. James Hutchings vividly described that flood:

On Dec. 23, 1867, after a snow fall of about three feet, a heavy down-pour of rain set in, and incessantly continued for ten successive days. . . . Each rivulet became a foaming torrent, and every stream a thundering cataract. The whole meadow land of the valley was covered by a surging and impetuous flood to an average depth of 9 feet. Bridges were swept away, and everything floatable was carried off. And, supposing that the usual spring flow of water over the Yo Semite Fall would be about 6 thousand gallons per second, as stated by Mr. H. T. Mills, at this particular time it must have been at least 12 or 14 times that amount, giving some eighty thousand gallons per second.20

[20. Hutchings, In the Heart of the Sierras, 492.]

Nothing was left of the new bridge built by the commissioners, although the timbers of Hutchings’s bridge were carried only a short distance away. A traveler to the valley in April 1868 mentioned that he found that the valley

had been nearly all overflowed during the past Winter. The water was up to his [Hutchings’s] hotel, all around his Winter cabin, and over his garden. It was nearly six feet higher than Hutching’s [sic] bridge, (or rather where the bridge was)—for it lays on the bank below. The covering can be made available for another bridge, which is already being built, and will probably be ready for use as soon as travel will commence. All the bridges are carried away; a small portion of Yo Semite bridge remains in a wretched condition; the fences are mostly washed away, and the general damage done is very great; the ferry boat has gone, together with the tree to which it was fastened. . . .21

[21. “A Trip to the Yo Semite Valley on Snow-Shoes,” Mariposa (Calif.) Gazette, by G. C., 17 April 1868; Mariposa (Calif.) Gazette, 10 April 1868. Hutchings replaced his previous log bridge with a finished timber bridge with a superstructure. In 1878 the state replaced that with an all-metal, steel-arched iron truss bridge (Upper Iron Bridge, later Sentinel Bridge). In 1872 Hutchings noted that his bridge across the Merced was the only one in the valley. J. M. Hutchings, Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California (New York: A. Roman and Company, publ., 1872), 111. The Sentinel Bridge was refurbished in 1898 and used until 1918. A new concrete bridge, completed in 1919, was widened in 1960. Another iron truss bridge was built about 1878-79 at the foot of Cathedral Rocks. Destroyed during the heavy winter of 1889-90, for many years its wreckage lay across the river alongside the new timber bridge that replaced it before the ironwork was finally salvaged. To prevent destruction of valley bridges by heavy snow loads, it was the practice for many years to rip up the plank flooring of some of them just before the snow fell, leaving the floor timbers open until spring. Laurence V. Degnan to Douglass H. Hubbard, 8 August 1957, in Separates File, Yosemite-Bridges, Y-19, #2, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

The major tasks facing the commissioners in the years immediately following passage of the Yosemite act involved increasing visitation by improving access routes, accommodations, and rates for visitor services, and at the same time exercising some control over development and land use. The first step in accomplishing these goals was to acquire all structures and land in the new park.

3. Settlers’ Claims

Prior to the establishment of the state grant, land in Yosemite Valley was a part of the public domain and therefore open to pre-emption and settlement under the homestead laws of the United States. Because the land was unsurveyed, no plats were filed in the U. S. Land Office. Locations given simply by metes and bounds were entered on the county records and considered to be legal guarantees of title until the land was surveyed.

The Yosemite act stipulated that the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Big Trees would no longer be open to homestead entry. Instead, ten-year leases would be granted for portions of the park, with the incomes derived from the leases to be used for the preservation and improvement of the grant and its roads, two obviously incompatible activities. Although proponents of the Yosemite bill, in an effort to eliminate delays, had assured Congress that there were no settlements in the valley, several claims had, in fact, been filed prior to passage of the legislation. Those individuals had occupied land in good faith under the pre-emption laws of the United States, and several had also bought the improvements of earlier settlers for rather large sums of money, assuming that their rights would be protected despite the new conditions.

The two men especially concerned over the prospect of losing their Yosemite Valley property were J. M. Hutchings and James C. Lamon. Another was Ira B. Folsom, who owned the ferry across the Merced River and the ladders at Vernal Fall. Although other people claimed houses and land in Yosemite Valley, they did not officially petition the commissioners. Many could probably not have claimed rights on the basis of permanent residence.

According to a petition by Hutchings, the 118 acres he and his family had settled upon had been homesteaded as early as 1856 by Gustavus Hite, Buck Beardsley, and others. In 1858 and 1859 Hite had built the two-story Upper Hotel on the site and a bridge across the Merced River. In addition he had cultivated the land and planted fruit trees. Hite ultimately went bankrupt, and his title to the land and improvements had been sold at public auction to Sullivan and Cashman of San Francisco. The property was then leased to various parties until the spring of 1864, when Hutchings purchased the rights and improvements and moved his family to Yosemite Valley.

Hutchings proceeded to erect several farm buildings, consisting of a small log house, a large barn and shed, corrals, fences, a bridge across the Merced River, and another over Yosemite Creek. In addition to cultivating a vegetable garden and planting grapevines, he established an orchard of 200 fruit trees in the vicinity of the present Yosemite Village and set out strawberry, raspberry, blackberry, gooseberry, and currant bushes. He also grew cereals and grasses and dug irrigation ditches. Although Hutchings had made his improvements after the state grant was established, the commissioners decided to deal leniently with him because they felt that the development had been done with an eye to the preservation of the beauty of the valley. In addition, Hutchings had done more than anyone to publicize the wonders of Yosemite, through his California Magazine and his lithographic reproductions of Thomas Ayers’s drawings.

James Lamon, born in Virginia in 1817, had come to California in 1851 and worked in the sawmill and lumber business in Mariposa County until 1858. After visiting Yosemite in 1857 and 1858, he bought the possessory rights of Charles Norris, Milton Mann, I. A. Epperson, and H. G. Coward, who had filed on 160 acres each. The land had not been officially surveyed nor had the original petitioners validated their claims by residence or improvement. Lamon took possession of 219 acres in 1859 at the upper end of Yosemite Valley, east of the present Ahwahnee Hotel and north of Curry Village. Near the junction of Tenaya Creek and the Merced River, he built the first log cabin in Yosemite and established the first bonafide homestead through settlement.

In 1861 Lamon filed claim to another 160-acre homestead. In the vicinity of the present concession stables, he established two orchards of about 500 fruit trees each, bearing apples, pears, peaches, plums, nectarines, and almonds; planted more than an acre of strawberry, blackberry, raspberry, gooseberry, and currant plants; cultivated several acres for a vegetable garden; sowed crops; and constructed irrigation ditches, cabins, and outbuildings.22 He also helped construct the Upper Hotel in 1859. At first Lamon lived in the valley only during the spring and summer, moving to the foothills when snow fell; he later became a year-round resident. Lamon sold the products of his orchards and garden to early hotel keepers and tourists.

[22. “The Settlers of Yo-Semite. Memorial of J. M. Hutchings and J. C. Lamon.” (To the Senate and Assembly of the State of California), December 1867?, in library, Society of California Pioneers, San Francisco, California, 1-2; National Register Nomination—Inventory Form, Lamon Orchard, 5 October 1975.]

Public opinion tended to oppose the maintenance of such homesteads, although most Californians felt that Hutchings and Lamon should not be ejected without liberal compensation for their loss. Some believed that because the state could not conduct farming, gardening, or hotel keeping services for visitors, men such as Lamon and Hutchings should be allowed that privilege. On the other hand, the Mariposa (Calif.) Gazette reported:

We have heard considerable complaint on the part of visitors to the Yo Semite Valley about the fencing in of the better part of the grazing land. By this the parties going there have trouble in obtaining proper grazing for their animals, and are annoyed in passing through the Valley. . . . Whatever may be the squatable [sic] rights of these individuals [Hutchings and Lamon] it is evident that their fencing in any part of the Valley will prove a nuisance so far as it effects the public, and is contrary to the evident intention of Congress. . . . The law enacted by the last Legislature gives ample power to the Commissioners to take charge of this property, and to remove all intruders. It is certainly the desire of the people . . . that this law be strictly enforced. . . . they [Hutchings and Lamon] should receive a favorable consideration . . . but they should be required to keep their fences down, and the lands claimed or occupied, free for all to pass over.23

[23. “Yo Semite Valley,” Mariposa (Calif.) Gazette, 14 July 1866.]

It was evident even to the Yosemite commissioners that the claims of Hutchings and Lamon, because of the improvements that had been made, would have been valid under the laws of the United States if the land had been surveyed and opened to pre-emption. Because it had not been, and never would be now that it was in a state park, neither Lamon nor Hutchings nor any of the other settlers in the valley held valid title to the land they occupied nor could they hold any hope of ever obtaining a right to it in fee simple. Hutchings and Lamon protested that, in view of all the labor and expense they had contributed to open and develop the valley both for their families and for the public, it was unjust to wrest the fruits of their toil without warning or adequate recompense.

The Yosemite commissioners proposed to buy the claims of the valley settlers and lease the land back to them. Because Lamon’s holdings were inconspicuous, and in recognition of the useful work he had accomplished in the valley, the commissioners offered Lamon the best deal they could under the circumstances—a lease of the premises for ten years at a nominal rent of $1.00 per year. Hutchings’s long residence in the valley and his careful efforts not to mar the landscape, as well as the fact that his hotel was not a particularly lucrative proposition, disposed the commissioners to offer him the same arrangement—a ten-year lease of his 160 acres, including the hotel and house, at a low rent. Hutchings, however, still claiming the rights of a settler on the basis of having purchased land already pre-empted, and probably hoping that public sympathy would influence the legislature to grant better terms, refused to accept a lease or acknowledge the right of the Yosemite commissioners to the land, and convinced Lamon to do the same. At that point legal proceedings were instituted against both men as trespassers.24

[24. Report of the Commissioners to Manage the Yosemite Valley . . . For the Years 1866-7, 8-10.]

Fearful that they would be ejected from their homes, Hutchings appealed to the California legislature, asking that it grant him the land he occupied in Yosemite Valley under the National Pre-emption Law and the Possessory Law of California. In 1868 that body passed a bill, subject to Congressional ratification, allowing Hutchings the 160 acres of land occupied and improved by him at Yosemite, with the proviso that the state could lay out roads, bridges, paths, and whatever else was necessary for the convenience of visitors anywhere they wanted in the valley, even through homestead lands. The act would take effect after its ratification by the U. S. Congress.

Governor H. H. Haight was less sympathetic when Assembly Bill No. 238 granting lands in Yosemite Valley to Hutchings and Lamon reached his desk. He ultimately returned the bill to the legislature, leaving the responsibility for its passage with that body. His strongest objection to the act was that he believed it was a repudiation and violation by the state of the trust and related obligations that had been accepted with the specific intent of using it only for specific public purposes. Granting Hutchings’s request would be tantamount to approving conversion of the entire valley to private ownership.

Haight pointed out that although the grantees were only asking for a portion of the land, others in the valley also had made improvements and would want to retain ownership of them. With such a large portion of the lands withdrawn from supervision, it would then, be useless for the state to attempt to control the valley. Hutchings and Lamon, holding 320 acres, would in effect have a monopoly of the usable land in the park. Also it was imperative that public access to every part of the valley be unrestricted if this was to remain truly a public reservation as contemplated by Congress. Governor Haight suggested that it was improper for the state to take such approval action without the assent of Congress. Instead of setting such a dangerous precedent, he continued, the petitioners should be either paid the fair value of their improvements as of the date of the act of Congress establishing the grant or given a lease at a nominal rent for a certain term of years.25

[25. “Veto Message of the Governor in Relation to Assembly Bill No. 238, an Act Granting Lands in Yosemite Valley,” 4 February 1868, in Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, California, 3-4.]

The California legislature voted to approve the grant over the governor’s veto, and petitioned Congress to ratify their actions. Leading Eastern newspapers were adamant in their opinions on the subject of the alienation of lands in Yosemite. Pronouncing the action of the California legislators extremely unwise, a New York Tribune editorial reiterated the widespread feeling that Yosemite was not just a state park, but a pleasuring ground for the world:

Certainly, we do not think we make too large a claim when we ask of Congress, in the name of the whole country and of the world of civilized men, to refuse this petition. . . . let Congress absolutely refuse to acknowledge their [Hutchings’s and Lamon’s] right to settle upon the land itself, and so defeat the object for which the valley was ceded to the State. That object was one of the largest and noblest that any State any where, or at any time in the world’s history, has proposed to itself with a view to the health and enjoyment of its people; and the fact that the General Government gave the land for such a purpose, and that the State accepted it, showed a high state of civilization. Barbarian or half-civilized States do not so respect great natural wonders, nor propose to devote them to the enjoyment of the world. . . . If Californians do not see their own interests more clearly, and if they will not respect the rights of the whole country, it is the bounden duty of Congress to protect us in the possession of this most splendid of Nature’s gifts to the American people. . . .26

[26. “Yo Semite at the East,” New York Tribune, 24 June 1868, reported in San Francisco Bulletin and quoted in Mariposa (Ca.) Gazette, 17 July 1868.]

Although Congress pointed out that federal jurisdiction over the lands had ceased, its members proceeded to offer some comments. The House agreed with the state legislature’s decision, declaring that the two homesteads constituted so small a fraction of the entire valley that their retention in private ownership could in no way interfere with public enjoyment of the valley as a “pleasure ground.” Attempts to dispossess them, it was argued, could imply serious trouble for other settlers who in good faith had settled on public lands under the pre-emption and homestead laws of the United States. Many House members were sympathetic to Lamon and Hutchings, who they felt were not speculative squatters, but adventurous pioneers:

as regards the question of a pleasure-ground, it only concerns the comparative few who will have the means and leisure to visit the valley, and these could see and enjoy quite as much if its thousands of acres were carved up into smiling homesteads, whose owners would probably guard the valley as carefully as any official appointed by the State.27

[27. Report of Comm. on Public Lands on House bill no. 184 - “An act to confirm to J. M. Hutchings and J. C. Lamon their pre-emption claims in the Yo-Semite valley, in the State of California,” in U. S. Congress, House Committee on Public Lands, “The Yo-semite Valley and the Right of Pre-Emption,” no date, in Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, California, 10.]

The bill in favor of Hutchings and Lamon passed the House but was blocked in the Committee on Public Lands by the Senate. The resolution, therefore, was not acted upon before the final adjournment of Congress, and as a result the act of the state legislature had no force. Still refusing to accept leases, Hutchings and Lamon took their dispute into the courts. The District Court of the Thirteenth Judicial District found for the defendant Hutchings, a decision the governor and the Yosemite commissioners appealed to the state supreme court. In 1871 that body reversed the judgment of the district court. In 1873 Hutchings lost his final appeal in the U. S. Supreme Court.

Both the California Supreme Court and the U. S. Supreme Court ruled that the act of the state legislature granting Hutchings 160 acres of land violated two of the conditions of the trust—that the lands be held for public use, resort, and recreation, and that they be inalienable for all time. The U. S. Supreme Court noted that the act of the legislature was inoperative, by its own terms, until ratified by Congress. Congress had never taken that action and probably would never sanction “such a perversion of the trust solemnly accepted by the State.28

[28. John T. McLean, “A Statement Showing the wrong done to, and the pecuniary damage and loss suffered by, The Coulterville and Yosemite Turnpike Company (a Corporation) from the illegal action of the State ” January 1887, in Letters Received by the Office of the Secretary of the Interior Relating to National Parks, 1872-1907 (Yosemite), RG 79, NA, 2, 9-12.]

In 1874 the California legislature established the precedent for land acquisition in Yosemite by appropriating $60,000 to extinguish all private claims in Yosemite Valley, and the Hutchings interests, after bitter contention, were adjudged to be worth $24,000. Lamon received $12,000 as compensation for his claims; A. G. Black received $13,000 and Folsom $6,000. The balance of the fund was returned to the state treasury. Although Hutchings continued to refuse a lease, Lamon finally accepted one.

Hutchings, Lamon, and the other settlers in the valley failed to see how their efforts to commercialize and homestead the land and farm and hunt in the valley posed any threat to Yosemite’s unique beauty and wilderness character. Although the adverse decision by the U. S. Supreme Court engendered many ill feelings between the state and the valley residents, it helped insure the future of a new concept—that certain lands should be protected and preserved for the public good.

4. Trails

a) Early Survey Work

The beginning of tourism to Yosemite increased the state’s need to know more about the region in order to provide accurate travel information. As mentioned earlier, efforts began through public surveys to reproduce on paper the various features of the Yosemite wilderness and the trails penetrating it. The California Geological Survey cursorily surveyed the Yosemite High Sierra in 1863, but investigated more thoroughly from 1864 to 1867 as a result of the creation of the state grant. A party directed by Capt. George M. Wheeler, in charge of geographical surveys west of the 100th Meridian, labored in the Yosemite area in the late 1870s and early 1880s, and produced a large-scale topographic map of Yosemite Valley and vicinity in 1883. First Lieutenant M. M. Macomb, 4th U. S. Artillery Regiment, detailed to the Wheeler party, first surveyed Hetch Hetchy Valley in 1879.

The few old Indian trails and sheepherders’ paths that existed in the Yosemite region were rarely blazed or otherwise delineated so that it was almost impossible to plot them. The earliest maps show the old Mono Trail over Mono Pass, branching in the area of Tuolumne Meadows, with one arm cutting over to the north wall of Yosemite Valley where it was joined by the Coulterville Trail as it climbed from the valley to the north rim. Another arm passed over Clouds Rest and Sunrise Creek, across Little Yosemite Valley, up Buena Vista Creek, and then down to the foothills. The Mono Trail also connected with the Mann brothers’ 1856 trail by continuing from Little Yosemite Valley through Mono Meadow to Ostrander’s, near Peregoy Meadow on the present Glacier Point road. The early survey map also included a route from Ostrander’s to Sentinel Dome that the state survey party blazed in 1864. Travelers reached the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees by a trail from Clark’s Station, while a trail entered Hetch Hetchy Valley from a point on the Big Oak Flat Road between Sprague’s and Hardin’s ranches, west of the present Big Oak Flat entrance to the park.

b) Routes To and Around Yosemite Valley

Because of their high altitude, all of the early trails to Yosemite Valley were susceptible to heavy snowstorms beginning in the fall and continuing well into the spring, so that they could be used only a small part of the year. Only one route tried to avoid the heavy drifts of the high ridges by taking advantage of the lower, relatively snow-free passage through the Merced River Canyon. The Hite’s Cove route was suggested as early as 1871, one of its primary advocates being James A. Hennessey, who was cultivating a commercial garden in the area now encompassed by the town of El Portal. The proposed route started from the settlement of Hite’s Cove, on the South Fork of the Merced River some distance above its confluence with the main channel. A wagon road already connected that village with Mariposa. From Hite’s Cove the trail crossed the ridge to the Merced River, continued upriver to Hennessey’s ranch, then followed the river for a mile or so before diverging from the stream into the mountains and intersecting the Mariposa-Yosemite Valley trail at Grouse Creek. That route, probably based on a previously existing Indian trail, was not heavily used because of its discomforts and difficult grade. The later winter mail route for Yosemite Valley, however, connected Jerseydale and Yosemite via the trail through Hite’s Cove and along the Merced River canyon.

Charles Leidig stated that his parents, Fred and Isabel, came to Yosemite Valley in 1866 over a horse trail via Jenkins Hill down into the Merced River canyon. They then followed up the canyon to the valley, suggesting this is one of the earliest historic routes into Yosemite Valley.29 Lieutenant N. F. McClure, Fifth Cavalry, U. S. Army, shows a trail running along the north side of the Merced River to a point just below the Coulterville Road junction at The Cascades. The trail appears to originate from Hazel Green, allowing access from areas west of the present park. One branch comes south through Anderson’s Flat to Jenkins “Mill,” while the other comes south from Hazel Green through Big Grizzly Flat and the Cranberry Mine area.30

[29. Paden and Schlichtmann, Big Oak Flat Road, 278-79.]

[30. N. F. McClure, “Map of the Yosemite National Park,” prepared for use of U. S. troops, March 1896.]

In 1885 the Mariposa Gazette carried an article by James A. Hennessey, written from his ranch on the Merced River, in which he stated that a trip in August to Wawona with a cargo of vegetables and orchard produce had been his first excursion out that way for the season. He also reported:

My new trail from the ranch intersecting the Mariposa and Yosemite Road, one mile east of West Woods, is nearly completed. I passed over it this trip. As soon as I have this trail completed I will commence on another from Fish Camp to Fresno Grove of Big Trees and the California Saw-mills. After that I expect to improve the old Mono and Mariposa Trail. With these trails in proper condition I can reach Tioga from my place in forty-two miles. This route would take in West Woods [Eleven-Mile Station], Peregoy’s Meadows, Little Yosemite, Clouds’ Rest Mountain and Soda Springs. It will be an excellent route and will bring plenty of tramps through to the county after it becomes known.31

[31. 15 August 1885, in Laurence V. Degnan to Douglass H. Hubbard, 3 September 1957, in Separates File, Yosemite-Trails, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

c) Tourist Trails in the Valley

One of the major deficiencies of the Yosemite Valley floor was the lack of footpaths enabling visitors to enjoy short walks from their hotels to scenic points of interest. Only a narrow boardwalk led from Black’s Hotel to the Upper Hotel. By 1864, however, two improved scenic trails out of the valley already existed, one to Vernal Fall, the other to Mirror Lake. The beginning of much of the present Yosemite trail system was laid after establishment of the state grant, when it became imperative that the Board of Yosemite Commissioners improve the faint Indian trails so that eager hikers could reach the valley rim and backcountry beyond. The small annual legislative appropriations could not accomplish extensive trail work or many other improvements on grant lands. As a way of raising revenues, therefore, the commissioners extended toll privileges for a specific length of time for trail construction just as they had for roads. Under that system, various grantees constructed the Four-Mile, Snow, and Eagle Peak trails. In 1882 the commission purchased the Mist and Glacier Point trails and soon after bought the others. The state did little further trail building on the valley up to 1906. Trail building in the backcountry was accomplished by the U. S. Army after 1891.

(1) Four-Mile Trail to Glacier Point

James McCauley, an Irishman, came to Hite’s Cove, California, in 1865 to mine. In 1871 he entered into a contract agreement with the Yosemite commissioners to build a toll trail from the south side of the Yosemite Valley floor up to Glacier Point. McCauley selected John Conway to survey the route and build the trail. Conway was one of the most famous trail builders in Yosemite, making many of the points on the valley rim accessible to later visitors. Conway and a trail crew began work in late November 1871 and worked until snow stopped their progress. Starting up the next spring, they had completed the trail to Union Point when Conway was injured in an accident. Because they had completed the survey to Glacier Point, trail work continued to completion in early summer 1872.

Helen Hunt Jackson described the Four-Mile Trail as

. . . a marvelous piece of work. It is broad, smooth, and well protected on the outer edge, in all dangerous places, by large . rocks; so that, although it is far the steepest trail out of the valley, zigzagging back and forth on a sheer granite wall, one rides up it with little alarm or giddiness, and with such a sense of gratitude to the builder that the dollar’s toll seems too small.32

[32. H. H. [Helen Hunt Jackson], Bits of Travel at Home (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1894) 127. She also mentioned stopping to rest at Union Point, where she thought McCauley evidently lived, “in a sort of pine-plank wigwam, from the top of which waved the United States flag.” Ibid., 133. This was more likely an equipment storage shed.]

In the 1920s the Park Service slightly rerouted the trail and changed its grades until it is now nearer five miles long; it still, however, retains the historic name. When the Yosemite Valley commissioners initiated their policy of eliminating all private holdings as rapidly as possible, they requested $7,500 from the state legislature in 1877 to purchase trails from their private owners. An act for the purchase of trails in Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove finally passed in March 1881. As stated previously, that bill appropriated $25,000 from the state treasury, part of which was intended for purchasing and making free the trails within the Yosemite Grant constructed and controlled by private individuals. In 1882 the state purchased the Four-Mile Trail from McCauley for $2,500 and made it toll free.

The old abandoned trail parallels the present one up the talus slope below Sentinel Rock. It begins on the valley floor about fifty yards east of the present trail and proceeds via five switchbacks to the base of Sentinel Rock, which it avoids by swinging 1,300 yards to the east. After another 200-yard swing to the west, the old trail enters another series of switchbacks to avoid a short rock-filled chimney at an elevation of 1,200 feet above the floor. From there to Union Point is another irregular series of zigzags, turning to the east and southwest, a prime example of Conway’s engineering competence. Union Point is 2,314 feet above the valley floor, and from there one can see Yosemite Fall, Half Dome, North Dome, El Capitan, Cathedral Rock and Spires, and the Big Oak Flat and Wawona roads.

The trail continues in several long, gentle switchbacks to an elevation of 7,000 feet. There it squeezes east under and over precipitous granite cliffs, emerging within sight of Glacier Point’s overhanging rock. Then the early-day hiker followed a level stretch of trail and made the last climb of a 100-yard rise to Glacier Point.

The impressive engineering and construction skills of the builder are apparent everywhere. Abandonment of the trail and construction of the present one in 1923 have hastened obliteration of the old trail, but only in the narrow, rock-filled chimney below Union Point is one unable to follow its course. The modern trail, paralleling the old, traverses an additional 0.6 mile to eliminate a one-step grade. The present Four-Mile Trail, therefore, is actually 4.6 miles long.33

[33. “Pioneer Trails of Yosemite Valley: The Four Mile Trail,” author unknown, in Separates File, Yosemite-Trails, Y-8, Yosemite Research Library and Records Center.]

(2) Indian Canyon Trail

This deep ravine in the wall east of Yosemite Point sheltered an Indian trail to the north rim of the valley. In 1874 James Hutchings paid for construction of a horse trail up Indian Canyon to Yosemite Point, which by 1877 had already fallen into disrepair. Construction of Conway’s Yosemite Fall and Eagle Peak trail made this one obsolete. The trail carried traffic for only a few years. Cosie Hutchings Mills recalled in 1941 that Fred Brightman, while working at the livery stable in the valley, had attempted to construct a trail up Indian Canyon, possibly between 1885 and 1888, but had been deterred from completing it by a huge rockslide.

(3) Yosemite Fall and Eagle Peak Trail

In 1867 James Hutchings reported that during the winter he had constructed “a good, substantial bridge across the Yosemite Creek . . . so that parties can now visit the foot of the lower Yosemite Fall with more comfort and less danger than formerly.”34 John Conway started the Yosemite Fall toll horse trail in 1873 and first completed it just to the foot of Upper Yosemite Fall. By 1877 he had finished the trail to the top of the fall on the north rim, and by 1888 to Eagle Peak. Conway refused to sell it to the state in 1882 for what he considered an unjust offer. It was subsequently announced in the Mariposa Gazette that the Board of Yosemite Commissioners had declared all trails and roads in the valley toll free, except for the Eagle Point Trail, whose owner refused to recognize the order of the board and surrender his franchise.35 Conway was finally forced to sell in 1885 for $1,500. The present trail closely follows the original.

[34. “Yo-Semite Valley,” in San Francisco Alta, quoted in Mariposa (Ca.) Gazette, 1 June 1867.]

[35. 10 June 1882, in Laurence V. Degnan to Douglass H. Hubbard, 3 September 1957.]

(4) Rim Trail, Pohono Trail

The Pohono Trail route appeared on Lieutenant McClure’s 1896 map, but its original builder and date of construction are uncertain. Originally an Indian trail, it led from Yosemite Valley up past Old Inspiration Point. The rim trail, which meets the Pohono, was constructed in parts by the state during the 1890s and taken over by the cavalry after 1905. About 1906 the trail’s name changed from Dewey Trail to Pohono Trail. The rim trail follows the south rim of the valley from near Sentinel Dome, via The Fissures, deep rock clefts just east of Taft Point, across Bridalveil Creek some distance behind Bridalveil Fall, then on to Dewey and Stanford points and the old stage road at Fort Monroe. It joined the early trail from the South Fork to Charles Peregoy’s Mountain View House in present Peregoy Meadow, which was practically abandoned after 1875 when the Wawona Road was completed to Yosemite Valley. That Alder Creek Trail, one of the oldest in the region and a main early route to Yosemite, led from Wawona through Empire Meadow, across the headwaters of Alder Creek, and along the level to Westfall and Peregoy meadows, and eventually struck the Pohono Trail. One can then turn left to the valley via Old Inspiration Point roughly along the route of the original Pohono Trail or turn right toward Glacier Point.

(5) Clouds Rest and Half (South) Dome Trails

The original trail to Clouds Rest formed a segment of the old Mono Trail. In 1882 the commissioners had recommended that the trail be shortened, which was accomplished, along with improvements, in 1890. In 1912 the Department of the Interior further improved it. Wheeler’s map also showed the spur trail to the base of Half Dome. Although several others, including James Hutchings, had earlier attempted to scale the 8,892-foot monolith of Half Dome, George C. Anderson, the Scottish blacksmith of Yosemite Valley, was the first to finally climb it, on 12 October 1875. A carpenter and former seaman, and prominent in the early trail building days of Yosemite, Anderson accomplished his climb of Half Dome with only drills and a hammer. By driving wooden pins and iron eyebolts into the granite five to six feet apart, he could successively fasten a rope to each bolt and pull himself up, resting his foot on the last spike while he drilled a hole for the next. He followed this painstaking process for 975 feet. Within a week six men, including Galen Clark, then age 61, and one woman, pulled themselves up to the top by Anderson’s rope. John Muir was the ninth person to make the climb, on 10 November 1875. Anderson’s plan of building a staircase to the summit of Half Dome died with him when he succumbed to pneumonia on 8 May 1884.

The cable that Anderson fastened to the bolts enabled Half Dome to be scaled for several years thereafter by the few who dared to meet that challenge. During the winter of 1883-84, sliding ice and snow broke the rope Anderson had installed and ripped out some of the eyebolts. It was again impossible for others to reach the top until several mountaineers duplicated the original climb and replaced the rope. The ropeway had to be replaced again in 1895 and 1901. Park Supervisor Gabriel Sovulewski recalled that Paul Segall replaced old pegs in 1908. John Muir wrote in 1910 that no one had

attempted to carry out Anderson’s plan of making the Dome accessible. For my part I should prefer leaving it in pure wildness, though, after all no great damage could be done by tramping over it. The surface would be strewn with tin cans and bottles, but the winter gales would blow the rubbish away. . . . Blue jays and Clark crows have trod the Dome for many a day, and so have beetles and chipmunks, and Tissiack would hardly be more “conquered” or spoiled should man be added to her list of visitors. His louder scream and heavier scrambling would not stir a line of her countenance.36

[36. Shirley Sargent, John Muir in Yosemite (Yosemite, Calif.: Flying Spur Press, 1971), 24.]

(6) Vernal Fall and Mist Trails

The Vernal Fall Trail started at Happy Isles and followed the south bank of the Merced canyon to the vicinity of Clark Point. From there one could take either the Mist Trail, passing along the steep cliffs of the Merced and enveloped much of the way with spray from Vernal Fall, or the regular Merced River Trail. The latter is one of the most historic trails in the park, forming one of the earliest segments of the present trail system.