[click to enlarge]

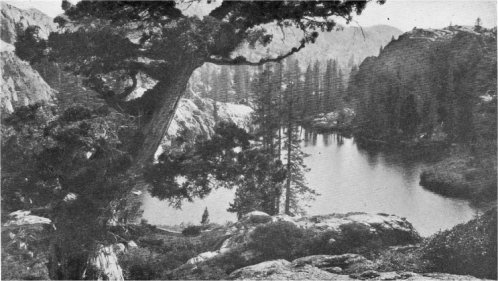

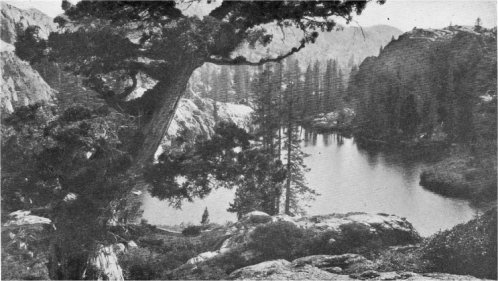

OUR LAKE IN JACK MAIN CAŅON

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Yosemite Trails > 14. The High Sierra: The Till-Hill to Lake Benson >

Next: Lake Benson to Lake Tenaya • Contents • Previous: Hetch-Hetchy to Till-Hill

Following a Sunday of sheer laziness, daybreak found us stirring, and by six o’clock we had breakfasted, packed, and were passing up the dew-drenched meadow. At the east end of the valley the trail divides. One branch doubles back to south and west, and connecting with the Rancheria Mountain trail, enters the Hetch-Hetchy at its upper end. We took the other, which swings northward and climbs by zigzags around a peak whose perpendicular crags are built up in tiers like the pipes of a gigantic organ. To the west stood the strong cliffs of the Hetch-Hetchy, and southward a break in the long, flowing ridge of Rancheria Mountain showed the gleam of snow on a higher summit, which Bodie figured would be “off around White Wolf and Smoky Jack.”

The morning was cloudless, and blue mist was pouring into the caņon with the sunshine. Through it the meadows of the Till-till and the great ledge of shining rock gave back quick lights like an opal. The sun waxed hot and hotter, and packs shifted with disgusting frequency. There was no sign of the trail having been travelled this year, but tracks of bear, deer, and mountain-lion were unusually plentiful, and grouse boomed in the scrawny, low-growing pines and junipers. A dull and simple-minded bird is the grouse of the Sierra. You may almost walk upon him before he will rise, and then he will but fly to the nearest branch and sit there in plain view, nearly tumbling off in his anxiety to get a good look at you. If you stop to pelt him with stones he does but gaze with deeper interest, quite unable to grasp the idea that the missiles that whiz past are directed at him.

Crossing the divide after a hard climb we passed under a high ridge, forested along the crest and sweeping down in slopes of grass and bracken such as you may see among the Welsh and English mountains. To the east a long barren caņon ran straight for miles to its head, where a line of snowy peaks rose sharply against the sky. Then came a long semi-meadow, edged with aspen and tamarack and sprinkled with violets, cyclamens, forget-me-nots, and, most exquisite of all, myriads of the large lavender daisies (Erigeron), which came to be, more than any other of my flower companions, my daily delight while I was in the high altitudes where it grows.

I could willingly devote a chapter to this most charming flower, so greatly did its beauty enter into me during my wanderings in the High Sierra. As with people, so with flowers, simplicity is what makes them lovable: and the compositae are all for simplicity. I suppose there is no flower that is so beloved as the common daisy; and if it were decreed that all flowers but one, which we might choose, were to be taken from us, this would be the one the world would elect to keep. All over the Sierra these choicest of daisies stand through the summer in countless myriads, giving the chance traveller his friendliest greeting, or in lonely unvisited meadows and forest ways smiling lovingly back at the sky. It is the flower that remains in one’s memory the longest, loved far beyond the rarer beauties of those solitudes.

An old cabin stood decaying on the edge of the meadow, and a mile or so farther on, another, its back broken by a tall fir that had fallen across it. A coyote sat on his haunches near by, so engrossed in the moral reflections appropriate to the scene that he did not see us until we were close upon him. Then he loped away with a ridiculous pretence of believing he had not been seen, though every shout sent him scurrying faster. A Clarke crow perched on a tamarack uttered remarkable sounds, expressive, I thought, of malicious pleasure as he watched his retreat. There were all the elements of a fable in the scene.

The trail climbed up among rocky ledges where clumps of pentstemon were blossoming with purple trumpets. Beautiful flowers are these, too; but without the fearless grace of the daisies with their open skyward look. Suddenly at a rise there came into view a long line of notched and splintered peaks only a few miles away, opening southward on a still higher and more distant line which marked the crest of the Sierra. A deep gorge opened below us, with lakelets and meadowlets strung along it, and lines of timber tracing every crease and rift of the granite, black on white, like a charcoal drawing. Down into it our trail seemed about to plunge, but swung abruptly off to the north by a little lake of ale-brown water, half full of fallen timber. Here I met my first Sierra heather (Bryanthus), with one spray of rosy blossom still waiting for me. I had been eagerly watching for the little plant which bore such a friendly name, and recognized it at once. I could not forbear kissing the brave little sprig of blossom, and stuck it in my sombrero for remembrance of bygone days on English moors and mountains.

Entering an amphitheatre of granite cliffs we wound steeply down a ledge trail into a caņon that trended northeasterly. Little pools clear as the very air, and pure and fresh as if just poured from a giant pitcher, filled all the rocky basins. These Sierra lakes and streams give one almost a new conception of water, not as something to drink or bathe in, nor as a feature of the scenery, but as the very element. It seems all but intangible, a mere transparent greyness, through which every boulder and splinter of rock on the bottom is seen almost more clearly than if there were no water there.

Passing down a rocky defile we dropped by the middle of the afternoon into what we guessed to be Jack Main Caņon, and fording a wide stream just below where it bursts from a gap of the mountains, went into camp on the farther side with ten or twelve miles of tolerably hard trail to our credit.

I have not been able to discover who Jack Main was, but I certainly commend his taste in caņons. A meadow incredibly flowery shares the valley at this point with a goodly river,—the same, as we found later, which flows into and out of Vernon Lake, and which lower forms the great Hetch-Hetchy Fall.

At this time, and for many days following, we were off the map, and were reduced to the sheerest guessing with regard to our whereabouts. Many and long were the debates around our camp-fires, where three distinct opinions usually developed, and were argued with all the obstinacy which is apt to mark discussions none of the parties to which have any real knowledge of the question in hand. In general terms, our problem was how to reach Soda Springs, somewhere away to the southeast. We were separated from it by a maze of rugged caņons, unknown to all of us, and all running transversely to our desired course.

The close of these discussions was marked, as regards our guide, by a docility that was almost child-like. He was willing, even eager, to defer to my judgment. Did I wish to follow this caņon farther? by all means we would do so. If I really believed we should cross that divide, he was mine to command. It was my party. He had told me he did n’t know this piece of country, but he was my devoted guide, and he and his animals would stay by me. When once he could get sight of Mount Conness, however distant, he would be able to locate us with ease and to pilot us handsomely to Soda Springs.

We camped among a clump of tamaracks at the head of the meadow. For a quarter of a mile below, the valley was an unbroken sheet of dwarf lupine, and was literally as blue as the sky. Botanists would find in these Sierra meadows an amazing revelation of Nature’s profusion. The wildling flowers stand as thickly as the grass of a well-kept lawn, waving in unbroken sheets of color from wall to wall of the caņons and around the margins of unnumbered lakes. In years to come pilgrimages of enthusiastic flower-lovers will wend to these delightful spots, where now only wild bees stagger in orgies of honey, and fairies dance by the light of the moon.

Investigation showed that we had camped better than we knew. Only a hundred yards above us was a charming little lake which had been hidden from us by the screen of trees. On one side it was fringed with aspens and firs; on the other, the rocky wall dropped perpendicularly to the glassy water.

The country about us here was the wildest we had yet seen, and considered as a prophecy was highly encouraging. Barren mountains rose high and close all around us, domed, peaked, ridged, and not even alloyed with timber except for the few scarred junipers that held the ledges, and seemed as old and gaunt as the mountains themselves.

[click to enlarge] OUR LAKE IN JACK MAIN CAŅON |

In the evening I climbed to a high point whence I looked down upon the lake, lying eclipsed almost as if in a well under the shadow of its western cliffs, but still mirroring the glory of the sunlit peaks in the north. Far below, the camp-fire twinkled cheerily. The sound of Pet’s bell floated musically up to me. Bodie, a black speck in the dusk of the valley, strolled down the meadow to review the transport department, and I caught on the breeze a stave of pensive sentimentality which seemed to reveal unsuspected deeps.

Slowly the light faded until only one great peak was left, shining like a beacon, solitary, white, pyramidal. As the sky darkened this glowed more brightly, seeming to collect and focus all the remaining light in the heavens. Then suddenly the grey shadow leaped upon it, and it appeared to sink and crumble like a burned-Out log. I climbed down and stumbled through the darkness back to camp, where I found my companions transformed into two mosquito-proof bundles, to which I quickly added a third.

Next morning we marched up the caņon, skirting the north shore of the lake. Granite cliffs still walled us in, and the trail lay over areas of glacial rock over which the river rushed in white cascades clown a wild and treeless gorge. Little half-acre gardens, shoulder high with grasses and flowers, occur even in this rough country, providing constantly fresh subjects of admiration and delight. By way of contrast I was never tired of noticing the quaint behavior of the junipers that were sparsely dotted about on the ledges of the caņon walls. There is a general resemblance in their deportment to the accepted portraits of Bluff King Hal, but while some are jovial fellows, holding their sides while they guffaw with inextinguishable laughter, others are like vicious Quilps and Calibans, sneering and fleering down so savagely that it is a pleasure to remember that they are rooted to their places.

A few miles and we came to another lake, lying in a meadow surrounded by rocky walls, and with a fine pyramidal peak at its eastern end. As we reached the higher altitudes, the mosquitoes became constantly more malicious and diabolical. Here they came at us ding-dong, like very Bedouins, biting savagely at every exposed part, careless of death so they could but once taste our blood. There is a deep pleasure in the reflection that untold millions of the creatures in these solitudes must live and die with that intolerable craving never once gratified.

The country here was sparsely wooded and the trail partly blazed and partly “monumented.” There is a humorous disproportion between this high-sounding word and the frail thing it represents. Two or three scraps of rock leaned together or placed one on the other to a height of a few inches, or a loose fragment perched on the top of a permanent boulder, constitute a “monument” in the language of the trail. It is by these feeble tokens that the track is marked through treeless country and over expanses of rock that hold no more sign of having been travelled than would a city pavement over which half-a-dozen persons a year might pass; and as they are often so far apart as to be hardly visible from one to the next, it behooves the traveller ignorant of his way to bear a wary eye. At the parting of main trails the monument may tower to three or four feet, but in general and over wide areas it is “like a tale of little meaning, tho’ the words are strong.”

From time to time I had caught glimpses of the great peak which I had watched at sunset. Now, fording the creek in rather deep water with a powerful current, that threatened for a moment the safety, without disturbing the equanimity, of our brave little Jenny, we made straight towards it. A white torrent came roaring over a cliff-like rise that fronted us, and beside this we climbed, the trail ascending like a stairway. I fancied that our straining animals eyed us indignantly as they clambered from ledge to ledge, all but Pet, who strode along as freely as if he were on a boulevard. Even here parterres of flowers, mimulus, pentstemon, and columbine, grew among the tumbled rocks, and mats of bryanthus hung in eaves over the margin of the stream.

As we gained the summit of the divide yet another lake came in sight, lying against the shoulder of the peak we had just rounded. From its shape we guessed it to be Tilden Lake,—a winding, river-like sheet of water, romantic to a degree, nearly two miles long, running in bays and reaches of placid silver between rocky shores. Files and companies of hemlock, dark almost to blackness, marched out on the promontories and clouded the magnificent sweep of the mountain sides. Looking up the lake to the northeast, there rose my great mountain, a superb shape, massive but symmetrical, beautifully sculptured with pinnacles and turrets and marbled with clots of snow. It was Tower Peak, rising to an altitude of 11,700 feet, one of the summit crests of this part of the Sierra. A little to the west stood another stately mountain, built up in unbroken slopes of granite that ridged up to a culminating precipice like the climbing surge of an ocean wave.

Bird-life is scarce in this high region, and I was surprised to see two swallows playing over the lake, which lies at 9000 feet. A fine adventurous spirit they must have, and a brave spring of romance there must be in their sturdy little hearts, to find out this lonely spot for their summer idyll. “Even thine altars,” said the Psalmist. Most true.

In the absence of maps we had no idea how near we were at this point to the divide of the Sierra. Tower Peak was not more than four miles away in an air-line, and on its northern face were the headwaters of the Walker River. I had not taken sufficiently into account the westerly trend of this part of the range, and we had all been misled by a preconception that the run of the cations was more easterly and westerly than in fact it is.

The lake continued in a chain of smaller lakes, and leaving these our trail swung to the south down a long, rocky caņon. We found ourselves now in a perfect maze, marching and countermarching, crossing divide after divide and creek after creek, until about two o’clock, tired, hungry, and puzzled, we straggled down a long descent and went into camp beside a loquacious stream in a grove of aspen and tamarack.

By the simple mathematical feat of moving the decimal point of supper two hours forward we secured a long evening of unbroken leisure. O the delight of those Sierra evenings! The blessed quietude, that lies on you like a soft pressure, and cools like a woman’s hand; the hushed talking of the stream as it runs around the bend, or laps and drains under sodden eaves of moss; the delicious rose of sunset-lighted snow-peaks; the always friendly companionship of trees; the purling soliloquy of the fire; the surprise of the first star, and the wistful magic of moonlight; the pleasant ghosts that sit with you around the fire and call you by forgotten nicknames; the old regrets that hold no sorrow; the old joys that do; the good snow-chill of the wind drawing steadily down the caņon; the quick undressing and turning in, and the instant oblivion—

—And the offensive suddenness of four o’clock in the morning, when we got up by half moonlight that cast our reluctant shadows on frost-whitened ground. Before six o’clock we had forded the river and were scaling the southern wall of the caņon, amid a heavy forest of fir, mountain-pine, and hemlock. The divine freshness and zest of the morning combined with the genial exhilaration of coffee and the cordial of the first pipe to raise our spirits to the point of song, and we were not surprised nor yet abashed, when jack for once broke silence and halted the cavalcade while he joined our chorus in lugubrious octaves.

Crossing the first divide we were in full sight of a deeply cleft crest which we took to be the Matterhorn peaks, but later found was the Sawtooth Ridge. We were near enough to them to note the terrible precipices that fall from the spiky pinnacles, trimmed even now in mid-July with snow-fields.

The opposite wall of the next caņon rose imposingly high and sharp, crowned with two dominating peaks. At each ridge we hoped to secure an outlook to south and east, by which we might gain a rough idea of our position from the bearing of the peaks of the Cathedral and Lyell groups; but always the high wall closed in our view, and we were fain to plunge into the caņons and climb the ridges one by one, with very little idea of how many more awaited us.

It was a day of flowers, especially a day of daisies. Almost equal to the impression produced by the power and magnificence of the mountains themselves was the pleasure I found in the continual appearances of these companions of the way. The characteristics of climate that render California remarkable for her abundance of flowers are not confined to the valleys of the state, but invade the mountains even to the limit of perpetual snow. Nor is it only in the forests and mountain meadows that the flowers congregate. Every ledge and cranny has its bush of pentstemon, or sprinkle of mimulus, or waving fringe of daisies. Around each pool and lake grow bryanthus and cyclamens, and from the midst of uncompromising boulders the great willow-herb (Epilobium) bursts in torrents of lively purple. Even on wind-scoured pavements the inch-high dwarf phlox will contrive to flourish, covering itself with pathetically tiny blossoms like pale little faces of children.

A dwarf variety of the manzanita also appeared here, blooming at this altitude two months later than in the lower valleys. Instead of the strong, elbowy shrub of the foothill and Yosemite levels, it is here a flat-growing, matted plant, creeping horizontally along the ground, its brittle twigs interlaced like a basket. Its Greek name of Arctostaphylos matches well with the brushy tassels of bloom, that are like little classic vases cut in alabaster.

In the next caņon the trail divided just before reaching the stream, and again we were put to guessing. The usual difference of opinion was in evidence, and on Bodie’s advice we took the westerly branch, which climbed through a gap and rounded a pinnacled peak. Here a cluster of lovely lakelets lay in deep pockets of the mountains, ringed with hemlocks. The beauty of these high Alpine lakes is perfect and delightful; but awful, too. There is a solemnity in their high-raised, unsullied purity and quietude, a divine openness like that we see in the faces of children.

Why does complete beauty, in which there is innocence, make us sigh? Is it that we are conscious of separation and reproach, and sigh, perhaps, less for the innocence that must be than for that which has been lost? There is solemnity, too, in the changeless passage of Time in these high solitudes. Like perpetual flowers these lakes have lain for unmarked centuries, giving back blue to the blue heaven or whitening to sudden silver as the roaming wind goes by. Through innumerable nights the slow courses of the stars have passed over the dark crystal of their waters. Years go over them like hours, seasons are no more than beats of a pendulum. Possibly the whole course of human history has run while these unnoticed pools have lain watching the inscrutable sky, awaiting the world-changes that to us are science, to them, perhaps, life (for how impossible it seems that through all the slow birth and growth of human intelligence, age by age, the earth itself should contract no consciousness, and suffer only passionless change).

Circling around the base of the pinnacled monster that guards the pass, the trail dropped steeply by a wild caņon where the ground was boggy with runnels of water from melting snow-banks just above us, and entered unexpectedly a dense growth of timber, where it was lost among windfallen trees. Casting about for it we came upon a larger oval lake, under the east shoulder of the mountain. This we found later to be Benson Lake, lying at 8000 feet, and the mountain Piute Mountain, with an altitude of 10,500 feet; but at the time we knew nothing of names or elevations, and every lake was a new surprise, so that our wanderings had almost the zest of original explorations. Our geographical senses were exercised continually in forecasting the probable run of the streams and caņons we encountered; and we were beginning to be occupied also with the question whether our supplies would hold out until we found the means of replenishing them either at Soda Springs or at the settlements on Mono Lake.

Here we pitched camp on a blue carpet of lupines and under the lee of a curving beach of white sand. This lake is about two hundred acres in extent, enclosed on three sides by rocky walls, quite precipitous in places and rising to four conspicuous peaks. The other side, the northern, is a beach of fine hard sand backed by a strip of meadow that merges into dense forest. One or two clumps of fir are wedged into gorges of the eastern wall, and push down to the water’s edge. A stream lively with trout rushes into the lake at the east end of the beach, which lies in crescent bays. A strong breeze blows continually from the south, sending the waves lapping noisily up on the beach, the wet sand of which bore a remarkable collection of autographs in the tracks of bear, deer, and other game, together with those of large wading birds. The smaller birds also were more in evidence here than we had lately found them, and the place seems to have attractions for a variety of creatures usually of very different shades of opinion. While we sat at supper in the dusk, a heron came sailing above our camp and alighted sociably in the top of a small tamarack close by, where it remained for some time observing our arrangements with interest, and quite careless of our notice.

Sitting on the shore of this delightful lake as night came down I revelled in the deep quietude of the place, while I watched the wavelets creeping in endless ranks out of the dusk and running playfully at my feet like kittens. The tree companies behind me seemed to move back and withdraw into the gloom. At half-past eight, one peak in the east, a sort of prong or tooth of granite, still caught the sun-glow, and towered up, a pile of rosy magic, into the clear, cold sky of early night. After my companions had turned in I sat for an hour or two by the fire, seeing again in the embers the long sunlit caņons, the grateful shadowy aisles of forest, the daisied meadows, the headlong cascades, the strong free sweep of the granite sea; and up there, two thousand feet overhead, where the bulk of Piute Mountain impended over me like a cloud, those little lakes, stark and open to the cold sky, with the ghostly snow-glimmer around them, waiting for the slow dawn of another day of the eternal solitude.

Before I turned in I took another look at the lake. The wind had changed to northerly, and the nearer half, sheltered by the ridge of sand, reflected placidly the surrounding mountains and the diamond glitter of the stars. The farther part was a dull gleam of steel. The moon was not yet up, but the high western peaks were beginning to catch her first light, and glimmered from an enhanced height with a look of unutterable age. The whisper of the creek pushing out into the lake kept all the air quietly athrob. Then from far up on the western precipice came the sharp report of a falling boulder, pried over by the sudden leverage of the frost. The sound grew into a hoarse rattle, and then to a thunderous tumult that reverberated in the hollow cup of the mountains like the roar of a monster trying in vain to escape. Gradually it lessened and sank into murmurs and mutterings, with word-like pauses and replies, dying away at last under some black rampart far down the lake. Then the singing voice of the creek took up again its quiet recitative.

Next: Lake Benson to Lake Tenaya • Contents • Previous: Hetch-Hetchy to Till-Hill

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_trails/till-hill_to_lake_benson.html