[click to enlarge]

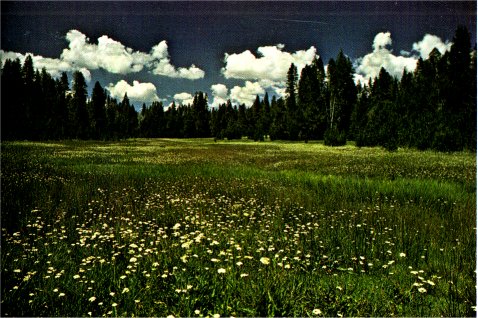

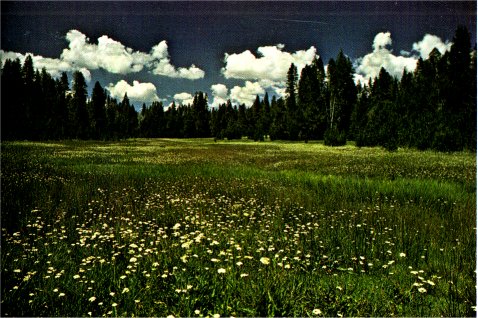

Yampah in Peregoy Meadow,

Perideridia bolanderi

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Wildflower Trails > Along Valley Rim Trails >

Next: Subalpine Belt • Contents • Previous: Yosemite Valley

The rims of this famous chasm, Yosemite Valley, rise more than 3,000 feet above the level parklands of its floor—creating a landscape of forests, meadows and granite domes amid a very different environment from the Valley itself. Here, on plateaus between 7,000 and 8,000 feet in elevation, we enter the region sometimes referred to as the Canadian Zone, since its flora and fauna resemble those found at the latitude of southern Canada. Another system of life zone classification, keyed more closely to the dominant plants of each area, refers to this rim country as the Lodgepole Pine-Red Fir Belt. These two trees are indeed. prominent in the forests at this elevation but in addition we find—in some quantity—Jeffrey pines, western white pines (sometimes called silver pines), Sierra juniper and aspen. The stately Big Tree, or Sequoiadendron giganteum, occurs just below this zone, reaching elevations in Yosemite National Park up to 6,500 feet, while another noble tree, the sugar pine, also flourishes at elevations just under the rim country.

This is a region of magnificent forests, embellished with silken green meadows, as well as open, gravelly slopes rolling up to the massive domes which are so typical of the middle elevations of the Park. Here and there small streams glide downward toward the Valley rims—streams with such memorable names as Yosemite Creek, Bridalveil Creek, Ribbon Creek, Sentinel Creek, Illilouette Creek—the very streams which fling themselves over these rims to drift down in misty columns of spray to the Valley floor as the famous waterfalls of Yosemite. In this splendid rim country is a unique combination of differing wildflower habitats: the moist meadows and streambanks—the dry, sun-drenched rocky slopes or “gravel gardens”—the deeply shaded humus of the forest floor under the red firs and lodgepoles. Thus perfect conditions are provided for a wide variety of flowering plants.

[click to enlarge] Yampah in Peregoy Meadow, Perideridia bolanderi |

There is a network of trails along each rim which will enable the hiker to penetrate as much of the region as he desires to see. For those not so inclined, or physically unable to walk this much at higher elevations, two fine roads permit driving through some representative portions of the best of the rim country. The Glacier Point Road follows along the plateau to the south of Yosemite Valley, reaching a maximum elevation of 8,000 feet and finally coming out to the rim itself at Glacier Point, 7,300 feet in elevation and directly above Curry Village, far below. To the north of the Valley, the Tioga Road climbs up to the rim and beyond, threading its way through a magnificent granite wilderness which is the approach to the eastern gateway of Yosemite National Park at the 9,941-foot Tioga Pass.

Let’s do a bit of flower hunting along these roads. After that, we’ll hike down the Pohono Trail which extends 13 miles along the south rim of Yosemite Valley, from Glacier Point to the Wawona Road at the tunnel. A walk on this trail, in mid-July, can provide one of the finest of wildflower adventures.

As one drives from Yosemite Valley up either of the two roads to the rim country in June or early July, one of the shrubs most certain to attract attention is the Deer Brush (Ceanothus integerrimus). Its small ovate leaves and tender stems are a favorite browse for deer. The fluffy panicles of white flowers, occasionally tinged with blue, resemble the form of the domestic lilac, hence another common name, California Lilac. This shrub may grow to heights of 10 to 12 feet and is encountered in quantity on mountain slopes between 5,000 and 7,000 feet elevation.

Several other species of ceanothus also are found in this area. A lower growing form produces powder-blue flowers and is more commonly seen along the Big Oak Flat Road below Crane Flat. Near Chinquapin, on the Wawona Road, a prostrate shrub called Fresno Ceanothus, or Fresno Mat (Ceanothus fresnensis), spreads across the open rocky slopes on the roadsides, with mats of tiny blue flowers scarcely raised above the foliage. Another type, also somewhat prostrate, but making wide shrubby mounds under the red fir forest, is the Snow Bush (Ceanothus cordulatus). Its blossoms make great heaps of white under the firs, resembling late-lying drifts of last winter’s snow.

Above the Wawona Tunnel, along the Glacier Point Road in June and July, a tall, slender plume of white waves in the breeze. This is Alum-Root (Heuchera micrantha var. erubescens), in the saxifrage family and somewhat reminiscent of that familiar garden flower, coral-bells. Rising out of a rosette of roundish, somewhat lobed leaves, the flower stalks, 1 to 2 feet high, produce panicles of minute white flowers, so delicate they seem to float unattached. This unusually graceful flower prefers dry rocky places, so it is often seen in road cuts and along trail sides. Even after the flowers have turned to seeds, the tall, silhouetted stalks and interestingly shaped leaves attract attention. In late summer, many of the leaves turn a bright red.

Another flower which often will he noticed as one drives either road in early- to mid-summer is the Blue Penstemon (Penstemon laetus). Its long, tubular blossoms range from blue to purple, and the upper ends of the petals are recurved to form an ideal landing place for bees, an important element in the pollination of these flowers, as they busily go in and out during their unending search for honey. The plants send up many flowering stalks, 1 to 2 feet high, and in full bloom the effect is of a mound of color. They prefer dry, rocky areas, and the contrast between the deeply saturated blue-violet tones of these blossoms and their background of light gray granite is exceptionally pleasing. Roadsides are frequent habitats for this penstemon; along the Tioga Road near the crossing of Yosemite Creek is a place it may be seen to advantage every year.

One of Yosemite’s most prized wildflowers occurs at moderate elevations along either road during July, the Washington Lily (Cilium washingtonianum). Although never appearing in large numbers, this majestic white beauty can be found, to at least a limited extent, each summer. Look for it on steep, well-drained slopes, preferably where low shrubbery gives it the necessary cover to permit growth and flowering, safe from browsing deer. Long stalks—up to 6 feet tall—carry several of these exquisite, trumpet-shaped flowers, reminiscent of Easter lilies. The blossoms are 3 to 5 inches long. Delicately fragrant, they have the white purity of new snow, with a few reddish dots on the petals. The long, slender leaves are arranged in symmetrical whorls at intervals along the stalk, producing in themselves a pleasing geometric pattern. Altogether a thrilling sight is the Washington lily. Look for it along the Wawona Road for several miles on either side of Chinquapin, and also on the Tioga Road for a few miles on each side of Crane Flat.

Near Crane Flat, in July and August, expect to find that unusual member of the sunflower family, the California Coneflower (Rudbeckia californica). Its tall stems, 2 to 6 feet high, raise the showy yellow flowers to a position where they are easily seen from the road. The sunflower-like blossoms are deep yellow, 4 to 6 inches across, the central discs of dark brown forming a cone 1 to 2 inches in height. No other sunflower in Yosemite has this distinctive feature in the blossom. For several weeks in midsummer during favorable years, the meadows near Crane Flat glow with its vibrant yellow. The coneflower may also be seen along the Wawona Road, though less spectacularly, and there is a good showing of it near Chinquapin, the Glacier Point road junction.

Frequently seen along either route is a bright red, low-growing flower preferring rocky locations, where it has established itself in crevices—often high above the road. This is the familiar Mountain-Pride (Penstemon newberryi), a long-time favorite of those who know and love the high places of the Sierra Nevada. Its flowers are tubular, 1 to 1 1/2 inches long, and occur in clusters on rather short, leafy stems which form masses of low foliage. During the period from late June to early August, mountain-pride is a familiar sight along roads and trails from 5,000 to 11,000 feet. Once you have identified it, this cheery little plant will be there to greet you again and again on many another mountain excursion.

One of the most pleasant aspects of the rim country is the number of fine mountain meadows to be enjoyed. Both roads and trails offer the traveler a splendid selection, and the month of July brings them to their peak of flowering beauty. The large meadow at Crane Flat and Summit Meadow on the Glacier Point Road are excellent examples. Each one has rather similar floral displays, the Crane Flat Meadow (which is somewhat lower in elevation) reaching its best stage in early July, with Summit Meadow doing so about two weeks later.

A dominant color in each area is the bright pink of the Shooting Star (Dodecatheon jeffreyi), which often is seen as a band of color across whole areas of the meadows’ expanse. Viewed closely, too, it is of great interest for its shape as well as its exquisite coloring, the inch-long petals turning backwards from the cluster of stamens as though blown by a streamlining blast of wind. These petals are deeply pink to lavender, or sometimes almost white, with yellow at the base and outlined by a maroon band. The flower stalks are erect, 6 to 20 inches high, and arise from a rosette of roundish basal leaves. Shooting stars, with small variations, are found from the foothill zone to 10,000 feet. This species, however, is the largest and most splendid of the Yosemite varieties.

When the shooting stars are in their prime, another unusual flower will he found sharing the boggy meadow areas. This one is the Camas Lily (Camassia leichtlinii ssp. suksdorfii), a deep blue to violet blossom of true elegance. A single erect stem, 1 to 3 feet high, rises from a whorl of long basal leaves, bearing at its tip 4 to 12 blossoms. Each consists of 6 petals, long and pointed, star-like, surrounding 6 stamens with bright golden anthers at their tips. The contrast between this brilliant gold and the royal blue of the petals is striking, while the clean lines of the flower’s structure make it especially graceful. Camas buds open late in the day, and the blossoms wither by the next day’s light, so one should plan to seek them in the afternoon. A meadowy expanse of these richly colored blue-purple lilies, accented with pink shooting stars, Is an experience not to be forgotten.

Another plant to look for in these bog-garden meadows is the Sierra Rein Orchid (Habenaria dilatata var. leucostachys), one of almost a dozen members of the orchid family in Yosemite National Park. It grows as a tall, thick stalk with clasping leaves, terminating in a spike of tiny, white flowers, each one about 1/2 inch long. These pillars of bloom stand 1 to 3 feet high in very wet areas, like ghostly accent marks to the meadows’ flowering statements. Although the individual blossoms are very small, their structure leaves no doubt they are true orchids. They are found in moist areas from Yosemite Valley to 10,000 feet elevation, from late May to early August; Summit Meadow, along the Glacier Point Road, is a typical habitat for them in July.

While wading into the boggy turf, look-for another dweller in the wet grasslands, the Lungwort, sometimes called Mountain Bluebell (Mertensia ciliata var. stomatechoides). On erect stems, 1 to 5 feet high, clusters of light blue flowers occur, often fading to pink. Their tendency to droop gracefully from the stem has given to them yet another common name, Languid Lady. Each blossom is a small bell-like tube about 1/2 inch long, a thing of beauty when seen in close-up, yet when the plant is in full bloom, it often makes masses of color. They prefer growing at the edge of moist meadows, rather than directly in the bog. One area in which they can be found is the upper or eastern end of the meadow at the Badger Pass ski bowl. The grassy expanse sloping down to Lukens Lake, one mile north of the Tioga Road, is also a prime location for the lungwort in early July.

Moist meadows are also the preferred habitat for another familiar Sierran plant, the Corn Lily or False Hellebore (Veratrum californicum). Its tall stalks (up to 6 feet high) are commonly seen in Yosemite’s meadows from 6,000 to 10,000 feet elevation in July and early August. A striking plant in all phases of its development, it has some resemblance to field corn, which tends to justify its common name, however superficially. As it first emerges from the meadow turf in June, its leaves are tightly wrapped around the stem, reminding one of an ear of corn which has been cut from the stalk and set down in the grass. The large, boat-shaped leaves open rapidly, finally becoming 10 to 16 inches long and 4 to 8 inches wide, with prominent ribs or veins. As the stalk attains its full height of 3 to 6 feet, it begins to “tassel out,” again reminiscent of field corn. The “tassels” consist of many white flowers about 3/4 inch across, with Y-shaped glands at the base of each petal. They are precisely formed and beautiful to see in close-up, but make a memorable display in mass as the entire flower cluster comes into bloom. A meadow full of tall corn lilies resembles a statuary garden, each one an individual work of art in traditional creamy white. Crane Flat Meadow is usually well supplied with this flower, while along the Glacier Point Road you will find the Badger Pass Meadow a likely place.

That same meadow at Badger Pass is a good place to seek out one of the showiest of the mimulus—the Pink Monkeyflower (Mimulus lewisii). Once seen, the blossom will not soon be forgotten, as its color harmonies feature a delicate pink to red tone with two brightly yellow, hairy ridges down the throat. It is a large flower, 1 to 2 inches long and 1/2 to 3/4 inches wide, usually borne in quantity on long stalks. The plant grows from 12 to 30 inches tall, producing numerous blossoms at the peak of its production. It is found in moist locations on the edge of meadows or along stream hanks. When traveling the Tioga Road, look for it in July and early August along the roadside just before reaching Smoky Jack Campground.

Another mimulus will reward those who watch closely for interesting floral effects along the Wawona Road. This is the Scarlet Monkeyflower (Mimulus cardinalis), one of the most brilliantly colored of Yosemite’s hundreds of flowering plants. It is bright scarlet in tone, the petals conspicuously two-lipped, with the stamens protruding. The blossoms are about 2 inches in length, and when the plant is in full bloom (July and August) it bears many of these handsome flowers, which contrast vividly with its bright green leaves. The stems are many-branched and from 1 to 3 feet tall. A fine display may be seen about two miles north of the Chinquapin junction, at a place where small springs drip down the steep slope to make a bog garden at the roadside. Scarlet monkeyflower also grows profusely along Tenaya Creek in Yosemite Valley, a short distance above the Tenaya Bridge and, in fact, may be found rather widely distributed between 4,000 and 7,000 feet elevation.

Another resident in the wettest meadow locations is the Marsh Marigold (Caltha howellii). Its brightly lacquered round leaves with scalloped edges are one of the earliest signs of spring’s approach, as winter’s snow is reduced to isolated, shade-protected drifts and sky-blue pools of melt-water replace it. In early June, the first of the creamy white blossoms appear, bearing 6 to 10 sepals (this little flower has no true petals) and a central mass of bright yellow stamens. For several weeks they brighten the moist areas along the Glacier Point Road; Pothole Meadow just ahead of the Sentinel Dome trailhead is a reliable place to see them. Marsh marigolds appear at the tips of 4- to 12-inch naked stalks, rising from a rosette of basal leaves. After the flowers have turned to the cycle of seed-setting, these leaves grow to larger size and become an interesting part of the ground cover of damp meadows.

The drier meadows, too, have their own roster of plants which are to be found only in such locations and which are among the most frequently seen of Yosemite’s flora. The bright blue-purple of Larkspur (Delphinium nuttallianum) is a prominent aspect of such meadows from June to August. Sometimes it gives deep violet tones to the landscape where myriads of blossoms occur together; in other locations only occasional purple spikes thrust skyward through the waving meadow grasses, on stems 8 to 24 inches tall. The blossoms are about an inch long, with 4 petals in unequal pairs. One of the 5 sepals is prolonged into an extended spur, the most distinctive feature of this plant, resembling the large spur on a lark’s back toe. Peregoy Meadow, adjacent to the Bridalveil Creek Campground, is a likely place to find larkspur, although it may be glimpsed in many other locations along both the Glacier Point and Tioga Roads where open sunshine and moderately dry soil give it the conditions it requires.

Peregoy Meadow is also an excellent place in which to find that delicate little member of the carrot, or parsley family, Squaw Root or Yampah (Perideridia bolanderi). On stems 8 to 30 inches high, slender and almost leafless, the terminal flowers appear to float as small pieces of lace work. The individual blooms are minute, only 1/4 inch wide, but they form umbels of purest white up to 3 inches across. The almost-Hat form of the blossom intensifies the lacy appearance which has suggested yet another common name, Queen Anne’s Lace. Along the Tioga Road, look for it as a broad expanse of white in Crane Flat Meadow and 3 miles above at Gin Flat Meadow as well.

In moist meadows and along stream banks is another frequently seen resident of damp places. The bright yellow of the Arrowhead Groundsel (Senecio triangularis) on tall stalks—2 to 6 feet high—is a familiar sight from July to September. The flower heads are small, 1/2 inch across, but they are numerous, forming clusters of bloom at the tops of the stalks like golden torches across the landscape. The leaves are a distinctive feature of this plant, making it easy to distinguish from the dozen species of groundsel found in Yosemite National Park. They are from 2 to 8 inches long, with toothed edges and in a distinctly triangular form, which has given the species classification to this senecio. It often grows near areas of large perennial lupine of this altitude, the contrasting blue-lavender of lupine with bright gold of groundsel providing a classical study in complementary colors. Badger Pass Meadow has fine stands of this flower, but it may be found in quantity along either the Tioga or Glacier Point Road from 4,000 to 10,000 feet elevation.

One more dweller in the moist meadows is sure to be noticed, its rich tones of magenta or rose-purple making a pleasing accent in the scenery of summer. This is the Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium), a plant of damp areas where forest fires, road work or clearings have removed other vegetation and given its wind-dispersed seeds a foothold. What a kindly provision has been made for the restoration of a devastated area, when flowers of such exquisite form and color can spring up so readily! This fireweed sends up tall stalks, 2 to 6 feet high, with many narrow leaves 3 to 5 inches long. The stalks end in racemes of bloom, clusters of 4-petalled flowers, deeply rose-purple, producing a climax of rich color. It reaches its peak in late July and in August. Look for it along the roadside near the junction to the Badger Pass Meadow. At Summit Meadow farther along the Glacier Point Road, fireweed is a prominent feature too. We will find a relative of this plant in the highest portion of the Park, at and above tree line in the rocky fell-fields.

Dry areas have their own species which brighten the roadsides and adjacent rocky slopes or may be found in the shade of deeply forested glens. One of the most prominent is the Sulphur Flower or Wild Buckwheat (Eriogonum umbellatum). Its varied shades of yellow and orange-red frequently are seen along either road between 6,000 and 9,000 feet, on open sunny flats, in granite sand. The plant is a mass of silvery gray sterns, 4 to 12 inches high, rising out of a rosette of small leaves, smooth and green above but white-wooly below. At the tip of each stem is an umbrella-like flower head of many tiny florets, the whole about an inch across. The total effect is of a brilliantly colored small shrub, sometimes butter yellow and at others a rich orange, adding vibrant hues to the quiet grays of the granite landscape. A typical place to see it is at the Sentinel Dome trailhead on the Glacier Point Road. In Tuolumne Meadows, the sulphur flower is a common sight as well—frequently seen in the vicinity of the Soda Springs and along the start of the trail to Glen Aulin. Expect to find it in July and August.

At the Sentinel Dome trailhead, inconspicuous in the lodgepole pine forest to the east, one may often find excellent individual specimens of Davidson’s Fritillary (fritillaria pinetorum), an unusual and handsome member of the lily family, well worth a little time spent in searching for it. The richly colored flowers, warm bronze in lone with a greenish-yellow mottling, stand erect at the tips of slender stems, which are 5 to 14 inches tall. With 6 petals, each flower is about an inch wide, forming a bowl-shaped blossom of striking appearance. The leaves are as slender as the stems, often occurring in whorls. It blooms in June and July.

At Washburn Point, near the end of the Glacier Point Road, is an area memorable for a beautiful flower often called Sierra Forget-Me-Not (Hackelia velutina). Another common name, less romantic but derived from the burr-like nutlet which succeeds the flower, is Stickseed. On the well-drained, gravelly slope a short distance above and to the south of Washburn Point—from here is a fine view of the Clark Range and Illilouette Basin —bloom myriads of this attractive plant. Its color in this location is delicate pink, but in other areas the same flower may be the deep blue of a summer sky, or perhaps a hybrid tone between the two. At the top of stalks, 1 to 3 feet high, appears a duster of blossoms, each one about 1/2 inch wide, blooming from late June to early August. The blue-colored version of this flower may be seen growing along the roadsides to the west of this point. An especially lush area for the deep blue forget-me-not is Crane Flat, where the Tioga Road turns east.

Travelers along the Wawona Road in late summer will notice occasional flashes of red by the roadside for some distance above the tunnel. This is the California Fuchsia (Zauschneria californica ssp. latifolia), a wildflower strongly reminiscent of the domesticated fuchsia so popular with gardeners. Tubular brick-red flowers, 1 1/2 inches long, with a widely flaring throat and projecting stamens, bloom profusely from early August through September. The plants are a mass of branching, hairy stems, 12 to 36 inches high, with many gray-green pointed leaves. They prefer dry, gravelly locations and can often be found along roadsides or on open rocky slopes. This blossom is a favorite of hummingbirds, attracted by its red color.

From mid-June to mid-August, a drive along the Glacier Point Road will disclose many other flowering species besides those listed above—the number seemingly limited only by the time and interest the visitor has to devote to the subject. Certainly, one will notice: the tall shrubs of Bitter Cherry (Prunus emarginata) by the roadside, with many clusters of small, white, plum-like flowers; the much larger white flowers, 2 inches across, of Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus); tall spikes of orange-hued Wallflower (Erysimum capitatum); wild Iris in variegated tones of buff and lavender (Iris hartwegii); Paintbrush (Castilleja miniata) flashing tall shafts of red-orange at the edge of damp meadows; the similar tone but strikingly different form of Columbine (Aquilegia formosa), distinctive red and yellow blossoms with long spurs; snow-white globes of Knotweed (Polygonum bistortoides) like stars among the meadow grasses; Western Pennyroyal (Monardella lanceolate), masses of gray-lavender blossoms in dry areas; the low, shrub-like Dogbane (Apocynum pumilum) with myriads of small, pink, tubed flowers; Sierra Currant (Ribes nevadense), a shrub of stream banks with handsome clusters of small rose-red flowers; the bright yellow, convex leaves and tiny purple blossoms of Shieldleaf (Streptanthus tortuosus); Pearly Everlasting (Anaphalis margaritacea) raising its small, silvery gray flowers in hedgerows along the road; rounded bushes of Red Elderberry (Sambucus microbotrys), with creamy flowers in midsummer and bright red berries in September; mounds of Spreading Phlox ‘Phlox diffusa), star-like flowers ranging in color from white through pink to lilac on dry slopes or rocky flats; Mule-Ears (Wyethia mollis), with bright sunflower-like blooms on 2-foot stalks and long-stemmed woolly leaves.

The same magnificent company of wildflowers will greet the traveler as he drives up the Tioga Road, too. However, this one reaches elevations as much as 2,000 feet higher than the Glacier Point Road, so that plants of the subalpine belt, or Hudsonian Zone, are encountered as well. We will become acquainted with a number of them as we hike around the High Sierra Loop Trail from Tuolumne Meadows, covered in the next chapter.

Those who travel through this favored land should have not only eyes to see but also ears that hear the music of the forest and the meadows. Mary Tresidder had both to an unusual degree, plus the ability to set down her impressions with great clarity; she once wrote, “All through these woodlands and at the borders of the meadows, such as in the Crane Flat area, bird songs fill the air in early morning and late afternoon. Most likely to be heard, if not seen, will be fox sparrows, chickadees, purple finches, juncos, warblers and the scarlet and yellow tanager that flashes like a flame from one tree to another. An occasional rarity such as the hermit thrush, whose song is in minor notes, may also be heard. Even the great gray owl has a favorite haunt or two in the area.”

Before we turn from the rim country of Yosemite to the higher regions of the Park, let’s leave our cars and follow a trail where the shyer wildflowers live, far away from asphalt and motor noises. We will walk the Pohono Trail; at the proper time, in mid-July, there is no finer display of wildflowers of the Lodgepole Pine-Red Fir belt to be seen anywhere. The trail is a long one, 13 miles on or near the south rim of Yosemite Valley, from Glacier Point to a junction with the Wawona Road at the east end of the Wawona Tunnel. It is possible to cut 3 miles off its total, by starting at the Sentinel Dome trailhead on the Glacier Point Road. But for our purposes let’s start at Glacier Point itself and walk the entire distance. This can be done in one day by anyone who is in moderately good physical condition as the trail follows the gentle up-and-down contours of the rim with no difficult hills except for the last 2 1/2 miles. Fortunately, for westbound hikers, this portion is downhill all the way to the tunnel.

Leaving Glacier Point, the trail climbs at first directly beneath Sentinel Dome, providing grand and unusual views into Yosemite Valley, over 3,000 feet below. One of the most memorable is the unobstructed view of the entire 2,400-foot drop of Yosemite Falls, directly across the canyon, an aspect of this waterfall unique to this position along the Valley’s rim. We are climbing through a splendid forest of Red Fir (Abies magnifica), interspersed with the dominant shrubs of this region—manzanita, chinquapin and ceanothus. Occasional flashes of color are provided by lupines, paintbrush and arrowhead groundsel in stunning combinations of blue, red and yellow. In early summer, this is a favorable area for the dramatic red snow plants, sometimes in groups of several large specimens. Here and there, the ground-hugging Pine-Mat Manzanita (Arctostaphylos nevadensis) unfolds its clusters of small, snow-white flowers like tiny urns, giving the foreground a glittering appearance. In dry, sunny areas, the orange-gold of sulphur flower is prominent, contrasting well with the subdued grays of the granite landscape. The brilliant rose-red of mountain-pride is abundant, sprawling recklessly across rocky outcroppings along the rim.

In a little less than two miles from Glacier Point we cross Sentinel Creek at the very place where it reaches the rim of Yosemite Valley and leaps over the edge in the first of a series of vertical cascades, to meet the Valley floor 3,300 feet below. Along the creek above the waterfall, interspersed with thickets of willow, are stream-side gardens of shooting-stars, lupine, wild asters, mountain violets. It is always rewarding to stand at the top of one of Yosemite’s waterfalls, looking down the descending torrent and being carried in fancy on the drifting comets of white water. Sentinel all provides a broad rocky overlook point where the temptation is strong to cancel the rest of the hike and remain here for the day, alone with one’s thoughts.

A climb of about one mile through open forests of red fir, Lodgepole Pine (Pinus contorta ssp. murrayana), Jeffrey Pines (Pinus jeffreyi) and occasional Western White Pines (Pinus monticola) brings us to the junction of the spur trail to the Glacier Point Road at the Sentinel Dome trailhead. This is a region of sunny, gravelly slopes blossoming with their own varieties of plants which are adapted to bright sunlight and well-drained, dry locations. In early summer, one of the most characteristic is the Spreading Phlox (Phlox diffusa) which forms prominent mats of white (sometimes lilac or pink), five-petalled flowers. The leaves are short, almost needle-like in appearance and texture. This plant is widespread across the Park, from 4,500 to 11,000 feet, adding a touch of delicacy to an otherwise rugged setting. A hardy perennial, its low-growing green mats can be seen through most of the period when snow does not lie on the ground, although its season of bloom is from June to early August.

Other flowers characteristic of these dry locations, and to be seen near this trail junction, are: pussy paws, golden brodiaea (similar to the one found earlier in the Sierran foothills), white-flowered Mariposa lilies, low-growing varieties of shieldleaf, the rich yellow tones of groundsel which is so prominent at this elevation, and the dainty little Collinsia (Collinsia torreyi var. wrightii) which grows only 6 inches high but may form solid expanses of delicate sky-blue and white blossoms.

Turning to the west, the Pohono Trail begins a gentle descent to the awesome overlook at Taft Point, about a half-mile farther. Almost at once, we pass through the first of many small, moist meadows where the silence is broken only by the water-music of a tiny stream and the melody of bird songs. These meadows, each a jewel, are among the memorable features of the Pohono Trail and provide distinctive habitats for a whole series of moisture-seeking plants.

One of the more showy species is the Little Leopard Lily (Lilium parvum)—sometimes referred to as Alpine Lily—which blooms on 2- to 4-foot stalks as a bouquet of numerous orange-yellow flowers with maroon spots. These flowers, 1 to 2 inches long, are tubular in form with some recurving at the ends of the petals, generally raising their heads as though to permit easy appreciation of their beauty. They put in their first appearance in late June and continue to flower until early August. Look for them in moist locations from Yosemite Valley (sparingly) to 9,000 feet.

Contrasting with the orange-yellow of this lily is the bright gold of the arrowhead groundsel, deep blue lupines on tall stalks (Lupinus latifolius var. columbianus), and showy heads of paintbrush. Wild Geranium or Cranesbill (Geranium richardsonii) is another typical plant of these moist locations, with rounded white or pink blossoms, strikingly veined in purple. Deer’s Tongue (Frasera speciosa) will he seen occasionally at the edge of these meadows—tall stalks 3 to 5 feet high with numerous greenish-white, star-shaped flowers.

At Taft Point, 3,500 feet above Yosemite Valley, is a rocky outcrop where the habitat changes again. Here is a typical location for that lacy member of the rose family called Mousetails (Ivesia santolinoides), because of the strange similarity of the leaves to the long slender tails of these little rodents. This plant has a branching net work of slender stems ending in minute white flowers which appear to wave in the air without visible means of support. Near the sheer edge of the rim grows the handsome shrub called Cream Bush (Holodiscus boursieri), with pointed racemes of small cream-white flowers forming dense shafts of bloom. Service-Berry (Amelanchier pallida), with five-petalled white flowers in random clusters is a tall, many-branched shrub also to be seen in bloom in this area. At ground level, look for a small Monkeyflower (Mimulus leptaleus) in contrasting tones of red and yellow, carpeting open areas among the forest trees.

The view from Taft Point is one of the finest along the south rim and deserves a long look. All the central part of Yosemite Valley is within sight, and the great north wall displays its varied structure from El Capitan to North Dome in an unbroken sweep. Nearby are large vertical cracks in the rim, known as the Fissures, where ages of erosion have removed the granite along joint planes in the rock, leaving narrow rewires of astounding depth.

As the trail heads west from Taft Point, it makes a wide arc to the south to descend into and climb out of the upper valley of Bridalveil Creek. Here we lose contact for a while with the Valley’s rim as we thread our way through a mixed forest of firs and pines. But there is much to see, for we are in a region pleasantly varied between inspiring forests, idyllic mountain meadows and songful streams. One of the charming plants to seek under the red firs is the little White-Veined Shinleaf (Pyrola pieta), whose favored habitat is the deep humus of the shaded forest floor. Typically, it grows 4 to 12 inches high with erect stems holding a cluster of greenish-white blossoms, like small bells whose clappers are the protruding styles of the flowers. Always, the leaves are in a basal rosette and are most attractive in themselves—deep green with prominent veinings of white. These rosettes are an appealing feature of the forest floor even before the flowers appear and after they have faded into the seed stage. Expect to find pyrola from late June to August, from 4,000 to 7,500 feet.

As we cross the several streams which drain the rim country and are in this region tributary to Bridalveil Creek, one of the frequently seen flowers is the Red Columbine (Aquilegia Formosa). Rather commonly found from 4,000 to 9,000 feet, it blooms from May to August as spring advances to higher elevations. The deep red-orange color of petals and spurs, combined with the bright yellow stamens which protrude boldly, form a rich tonal combination which has made the columbine a favorite wherever it grows. Nature has been generous in its supply of this lovely blossom, to the great pleasure of the hummingbirds who drink deeply of the nectar in the long spurs behind the petals. The plant itself often grows to a height of 3 to 4 feet where moisture is favorable, with leaves deeply and attractively lobed.

Along these streams, in the willow thickets and bog gardens, the Red Osier Dogwood or American Dogwood (Cornus stolonifera) grows lushly. Its bright purplish-red steers, 4 to 12 feet high, produce clusters of tiny 4-petalled flowers which form flat umbels of shimmering white on the shrub. Like its close relative, the tree-sized mountain dogwood, its leaves turn red in the fall, making one of the brightest colors in the autumnal landscape. In early spring, before the leaves develop, the lacquered appearance of its colorful stems and branches is a pleasing accent in the somber greens and grays of the forest.

The trail now twists through the tall trees, occasionally coming close to the rim providing dramatic and unusual views into Yosemite Valley, then skirting the edge of several jewel-like meadows—serene and untouched in their forest isolation. Here the moisture-loving plants which flower in July are to be found in abundance—whole congregations of midsummer’s most distinguished residents. Tall shafts of corn lily, bright areas of yellow monkeyflower, the nodding heads of rose-lavender wild asters, clusters of tiny bluebells or languid ladies, the vivid gold of groundsel and the scarlet of paintbrush, royal purple tones of delphinium—all combine in a palette of unforgettable color against a setting of emerald green grasses and mosses. One of the more charming of these dwellers in the meadows is a plant related to columbine, the Meadow Rue (Thalictrum fendleri), growing on stalks up to 3 feet high, with deeply— lobed compound leaves. The blossoms are especially interesting in their form, although their color differs little from that of the stems or the leaves themselves. Long stamens, faintly yellow, hang from the circle of 4 to 7 sepals, swaying in any slight breeze like a delicate fringe. This unusual plant has no true petals.

In these same wet meadows, tall shafts of Purple Monkshood (Aconitum columbianum) stand regally at the edge of the forest or near willow thickets. The stems are 2 to 6 feet high, with deeply lobed leaves. The distinctively shaped blossoms, 1 inch across, have a striking resemblance to the traditional hood of a monk, covering the face of the flower with a dark purple, sombre color. The plant is said to be poisonous, and grazing animals avoid it.

About 2 1/2 miles from Taft Point, our trail crosses Bridalveil Creek, a robust stream which flashes along a sloping, forested valley, singing its way through thickets of willow and dogwood with wildflowers thronging its banks, thriving in the cool dampness. A rustic bridge provides easy crossing, and nearby is an ideal place for lunch and perhaps a period of quiet contemplation of the unspoiled quality of this sanctuary. The beautiful stream is as yet unaware of its turbulent destiny, less than 2 miles distant, for at the Valley’s rim it will plunge over the 600-foot cliff to form spectacular Bridalveil Fall, a creature of mist and rainbows.

Just beyond the creek crossing, a lateral trail may be taken to the south, intersecting the Glacier Point Road near the Bridalveil Creek Campground. This trail is only slightly more than 2 miles long, taking one over the wide grassy reaches of McGurk Meadow and through long expanses of lodgepole pine forest. It makes possible the termination of the Pohono Trail hike at approximately its halfway point, if time is not available for the entire distance. Or, alternatively, one can start at Bridalveil Creek Campground and walk the remainder of the trail to the west, finishing at the Wawona Tunnel, a total distance of 9 1/2 miles.

As we pass the McGurk Meadow Trail junction, the main Pohono Trail ascends a gentle sandy slope which often holds a remarkable display of Scarlet Gilia (Ipomopsis aggregata). The scarlet hue will be noticed as a vivid mass before one is near enough to be aware of the individual plants. There are few other mountain flowers that can rival it in color intensity, while the structure of the blossom itself is of interest too. Growing on erect stems, 1 to 2 feet high, the bright flowers remind one of a sharply pointed star, trailing a comet-like tail which is the long tube from which the five petals explode. The red color is offset by a mottling of yellow along the slender petals, while horn the center emerges a cluster of bristling stamens. Gilia leaves are rather distinctive in their form: 1 to 4 inches long, divided into several minute and very slender sections. Scarlet gilia is a flower of dry, sandy slopes and will he found from 6,000 to 9,000 feet blooming from late June to mid-August. Look for it also along the Tioga Road at about the 8,000-foot elevation, and occasionally beside the Glacier Point Road as well. There is a notable display on the old Glacier Point Road, between the Badger Pass ski area and Bridalveil Creek Campground, a road which is closed to automobiles now but still affords a fascinating hike.

Magnificent red fir forest, interspersed with flowering meadows and small streams of cold, sweet mountain water continue to make the trail a constant source of happy surprises as we climb slowly out of the valley of Bridalveil Creek. Where the humus under the red fir is especially deep, look for an attractive member of the orchid family, the Spotted Coralroot (Corallorhiza maculata). Its brown stems rise 8 to 24 inches from the forest floor, with leaves which are mere clasping, papery sheaths. The flower head consists of 12 to 15 individual blossoms, varying in tone from magenta to chartreuse, but with a white lower lip which is usually spotted with crimson. Although each flower is only 1/2 inch long, there is no mistaking its relationship to the orchid family, for there is a close resemblance—in miniature—to the cultivated species. This plant is similar to the snow plant in that it lacks chlorophyll and hence is incapable of producing its own food in the normal way through photosynthesis. Through the aid of fungi growing in its roots, decaying organic matter in the soil is broken down for food. Spotted coralroot is not a common flower, but it does occur intermittently in the areas of suitably deep humus. The Pohono Trail is one of the best places to find it; another good location is in the general area of Glacier Point or Sentinel Dome, where the red firs provide the habitat it seeks. It blooms in July and August.

Dewey Point, at about 2 1/2 miles from the crossing of Bridalveil Creek, is an overlook where the hiker is tempted to linger indefinitely. The trail sign announces that this platform in the sky is 7,316 feet in elevation—about 3,300 feet above Yosemite Valley’s floor. Directly across the great chasm looms the famous cliff of El Capitan, its entire facade and vast sloping crest in full view. The lower canyon of Bridalveil Creek, terminating in the waterfall, slashes into the south rim of Yosemite directly to the east, while the summit peaks of the High Sierra lift jagged edges against the farthest eastern horizon. At Dewey Point, one feels alone with the sky and the wind, almost a fellow creature with the white-throated swifts that dart constantly from the rim far out over the canyon like tiny feathered projectiles.

On this rocky buttress grows one of the typical plants of the dry slopes, the little Stonecrop (Sedum obtusatum). Its stems are only 1 to 6 inches high, reddish in tone, arising from rosettes of fleshy leaves. The small flowers form clusters of lemon-yellow color, often fading to pink, 1/2 to 3/4 inch long. The whole effect is that of a carpet of warm gold thrown across the rocks, like congealed sunshine.

Heading west from Dewey Point, the Pohono Trail begins its long descent to meet the Wawona Road. It remains fairly close to the rim for the next two miles, offering climactic views into Yosemite Valley at several places. Just before reaching the next major overlook at Crocker Point (7,090 feet elevation), we cross another of those delightful little streams. Its cold, clear water encourages a lush growth of ferns, willows, red osier dogwood, yellow monkeyflower, meadow rue, groundsel, thimbleberry. From Crocker Point—well worth a stop—there is a memorable view of the full drop of Bridalveil Fall. In late afternoon, its rainbow is especially vivid as seen from this overlook.

A half mile farther is Stanford Point (6,659 feet elevation); the view from here consists of the same elements admired from Crocker Point, yet in a different scenic arrangement. The forest is now becoming the dominant feature of the trail, with huge mature specimens of Red Fir (Abies magnifica), Sugar Pine (Pious lambertiana) and Jeffrey Pine (Pinus jeffreyi) making up much of the woodland. On the dark maroon trunks of the red fir, the contrasting chartreuse of the Staghorn Lichen (Letharia vulpina) is especially prominent. It grows on the ridges of the bark and on dead branches, farming fur-like coverlets, 2 inches or more in depth, that seem strikingly brilliant against the somber tones of the forest. This lichen is an epiphyte, or air plant, deriving its sustenance from air and sunlight while using the trees only as a means of support. It does no harm, as a parasite would, to the tree on which it grows.

The last of the major overlooks along the Pohono Trail is Old Inspiration Point (6,603 feet elevation). Although no trail leads down to the actual point itself from the Pohono, it is not difficult to scramble through the manzanita and chinquapin brush to the place where in 1851, according to history, the initial party of white men to enter Yosemite Valley (the Mariposa Battalion) beheld their first view of the canyon they had been seeking. Their actual descent from this point to the Valley floor was to the west, the route followed closely today by the Pohono Trail.

Now the trail drops relentlessly for the remaining 3 miles to the Wawona Road. the red firs are seen no more, preferring the higher reaches of the rim country; their glace is taken by the White Fir (Abies concolor). Their trunks are dark grey to silver, their crowns a bit more spire-like than those of red firs, yet the trees are of comparable size. No festoons of staghorn lichen decorate them, however. Ponderosa Pines (Pinus ponderosa) come into the forest community in increasing numbers as the trail continues its descent. They will be found all the way to Yosemite Valley, where they are the dominant conifer. Long golden beams of late afternoon sunshine reach through the forest aisles. Huge Black Oaks (Quercus kelloggii) join the pines and firs; they too will be present all the way to Yosemite Valley. Beneath these forest monarchs Is an understory of shrubbery: manzanita, ceanothus (deer brush), azalea along moist water courses, rounded masses of Huckleberry Oaks (Quercus vaccinifolia). Often one can hear in the distance, almost dream-like, the rhythmic hooting or drumming of the male dusky grouse, a low but resonant sound that vibrates through the forest. Occasionally, a startled deer bounds away through the trees. The serenity of a mountain evening lies across the land like a benediction at the close of a memorable day.

Inspiration Point, only a mile from the Wawona Road and 1,000 feet above the well-known Tunnel View on that road, is the last major scenic landmark along the Pohono Trail. Here, the trail crosses the original Wawona Road, opened in 1875, at the place where early travelers to Yosemite stopped for their first inspiring glimpse into the famous valley they had come so far to see. The view remains unchanged today, for the National Park Service has safeguarded it against despoilment by roads, buildings or other man-made additions to the landscape, all of which are effectively concealed on the Valley floor. There is little doubt that this viewpoint offers the most comprehensive of all Yosemite Valley vistas—from Bridalveil Meadow just below us to Cloud’s Rest at the extreme eastern end of the canyon. This view always affords a Mood of tranquility as well as inspiration, yet it is one which is seen by comparatively few visitors.

One mile down the trail brings us to the Wawona Road, where we will welcome the chance to rest after long miles on foot. The farsighted will have arranged for transportation from here. Weariness may be the predominant feeling of the moment, but the day has been one of enriching memories of far-flung vistas, of the inspiring architecture of great trees, of sparkling meadows and singing streams, of the sight and sound of birds, and especially of a panorama of wildflowers not often excelled. In Yosemite’s rim country, the Pohono Trail is typical of the best of its widely varying flower habitats.

Next: Subalpine Belt • Contents • Previous: Yosemite Valley

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_wildflower_trails/valley_rim.html