| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Main Route >

Next: Chapter 15 • Index • Previous: Chapter 13

|

Speed the soft intercourse from soul to soul,

And waft a sigh from Indus to the pole.

—Pope’s

Eloise to Abelard.

|

|

Traveling is no fool’s errand to him who carries his eyes and itinerary with

him.

—Alcott’s

Table Talk.

|

|

Know most of the rooms of thy native country before thou goest over the

threshold thereof.

—Fuller.

|

There are probably but few, if any, more exciting scenes in any part of the world than are to be witnessed on almost any day, Sunday excepted, at the Market Street Wharf, San Francisco, upon the departure of the various trains for the interior, or overland. Men and women are hurrying to and fro; drays, carriages, express wagons, and horsemen dash past you with as much haste and vehemence as though they were carrying a reprieve to some poor condemned criminal, the last moments of whose life were fast ebbing away, and by the speedy delivery of that reprieve, they expected to save him from the scaffold. Indeed, one would suppose, by the apparently reckless manner in riding and driving through the crowd, that numerous limbs, if not necks, would be broken, and vehicles made into mince-meat! Yet, to your surprise, nothing of the kind occurs; for, upon arriving at the smallest obstruction, animals are reined in with a promptness that astonishes.

Interesting as this may be to you as a spectator, it should not be allowed to divert your attention sufficiently to prevent the timely checking of your trunk, or valise, to the very railway terminus you are to leave by stage, or to cause your being the proverbial “last man,” as he sometimes arrives too late. Presuming that all such matters have received becoming consideration; that your ticket, upon its face, provides for all emergencies of travel upon the route you have chosen; and, moreover, that you are safely aboard the ferry-boat that is speeding you towards the wonderful Valley and the Big Tree Groves; as you may be a stranger here, and somewhat unfamiliar with the scenes that will open before you, I will, in imagination at least, with your kind permission, be your traveling companion on this excursion, and explain such matters as most naturally will claim our attention.

As it is generally cool in summer, when crossing the Bay of San Francisco, please put on your overcoat, and let us take a cozy seat together on the north side of the boat; and while the black smoke is rolling in volumes from the funnels of numerous steamers, and we are shooting out from the wharf, past this or that vessel lying at anchor, or furling its sails from a voyage or spreading them for one; while numerous people are troubling about their baggage, and asking the porter all sorts of questions, let us have a quiet chat upon the sights to be seen around us. The first object of interest, after leaving the wharf and the city behind us, is

|

| ALCATRACES, OR PELICAN ISLAND. |

This is just opposite the Golden Gate, and about half way between the city and Angel Island. It commands the great land-locked Bay of San Francisco, and is but three and a half miles from Fort Point, on the southern side of the Golden Gate. This island (now generally called “Alcatraz”) is one hundred and forty feet in height above low water mark, four hundred and fifty feet in width, and sixteen hundred and fifty feet in length; somewhat irregular in outline, and fortified on all sides. The large building on its summit is a defensive barrack, or citadel, three stories high, which in time of peace will, with other quarters, accommodate about two hundred men; and in war about three times that number. It is not only a shelter for the soldiers, capable of withstanding a respectable cannonade, but from its top a murderous fire could be opened upon its assailants at all parts of the island. There is, moreover, a belt of fortifications encircling the island, mounting guns of the heaviest caliber, and of the latest improved patterns.

Besides these there are stone guard-houses, shot and shell proof, protected by heavy gates and draw-bridges, and having embrasures for rifled cannon that command the approaches in every direction. Their tops, like the barrack, are flat, for the use of riflemen. In addition to these there are several bomb-proof magazines, and a large furnace for heating cannon balls.

Unfortunately, no natural supply of water has yet been discovered on the island, so that all of this element has to be carried there in tanks, and stored in a large cistern at the basement of the barracks. For washing purposes a sufficient quantity is obtained from the roofs of the principal buildings. At the southeastern end of the island is a fog-bell, of about the same size and weight as that at Fort Point, which is regulated to strike by machinery every quarter of a minute. There is also a light-house at the south of the barracks, with newly improved lenses, the glare from which can be distinctly seen, on a clear night, some twelve miles outside the Heads, and is of essential service in directing the course of vessels when entering the Bay. Northerly from Alcatraces, about two and a half miles distant, and five from San Francisco, is

This contains some eight hundred acres of excellent land, and is by far the largest and most valuable of any in the Bay of San Francisco. The wild oats and grasses that grow to its very summit, in early spring, give pasturage to stock of all kinds needed here; while several natural springs, at different points, supply good water in abundance, and at all seasons. A large portion of the island is susceptible of cultivation for all kinds of vegetables and cereals. Beautiful wild flowers grow in sequestered places from one end of it to the other. Live oaks (quercus agrifolia) supply both shade and firewood. Belonging, as it does, to the Government, it is a favorite place of residence for army officers stationed there, for whose accommodation a small steamer plies, regularly, between this island (calling at Alcatraces, Fort Point, and Point San Jose) and San Francisco.

From its almost inexhaustible quarries of hard blue and brown sandstone, nearly all the material for foundations of buildings in San Francisco were taken, in early times. The extensive fortifications at Alcatraces Island, Fort Point, and other places, have been faced with it, and the extensive Government works at Mare Island have been principally built with stone from these quarries. Clay, also, in abundance, and of excellent quality for bricks, is found here.

As Angel Island lies midway between Aleatraces Island and the main-land the guns from its fortifications completely sweep the bay, southerly, and Raccoon Straits, northwesterly, affording thorough protection on all sides. But for these not only would our Navy Yard at Mare Island be in jeopardy, but the city of San Francisco itself would be exposed; inasmuch as an enemy’s war vessel could easily enter the harbor by Raccoon Straits, during a heavy fog, that frequently in summer hangs over the Golden Gate, if permitted to pass Fort Point in safety.

Is the highest point in the more immediate surroundings of the Bay of San Francisco, and is a more prominent landmark far out at sea. It stands northwesterly from the city of San Francisco, and its top is about fifteen miles distant, “as the crow flies.” Its height above sea level is 2,610 feet. A good road to its summit from San Rafael now enables every one to view the comprehensive and beautiful landscape thence, not only with comfort but with positive enjoyment. We generally climbed it afoot, for exercise. The light-colored mark on its southern side was caused by a “cloud-burst,” which literally tore out the earth and rocks to the depth of several feet, and for over forty feet in width by a hundred and fifty in length. This torrent-cut material, sweeping with impetuous force down a ravine, set bowlders free, tore out trees by their roots, snapped others in two, and made sad havoc from top to bottom. This event occurred in 1861. If I were to detain you here with descriptions of its madroñe, laurel, oak, and other trees; its fragrant shrubs, and numerous wild flowers, there is no telling when or where this theme would end. But while we have been chatting, and watching the receding city, with its seven hills—like Rome—all covered with buildings; or looking at the English, French, or German, and other ships-of-war that are now resting so peacefully at anchor, like sleeping giants; or admiring the daring of those little steam-tugs that shoot hither and thither, and take hold of vessels many dozen times their size, and push them wherever they may list; or interestedly note the craft of all sizes flitting across the seething wake of our boat, and glinting in the far-off sunlight; or listening to the beating paddles of numerous ferry-boats, starting in all conceivable directions; or observing that steamer with the stately sweep and build, whose prow so proudly cuts the brine, that is just now sailing for Panama, or Hong Kong via Japan, or Australia, or for one of the many Pacific Coast ports; while we have been observing these, and perhaps many other objects of interest, we have come abreast of a little green spot now known as

When occupied by Mexicans it was called “Yerba Buena Island,” from the generous supply of the “good herb” (Micromeria Douglasii) found on its northern and sheltered side. It is now in the possession of the United States Government, and used mainly as a Fog-Horn Signal Station—a very necessary precaution in foggy weather, especially to the well-patronized ferries that ply between San Francisco and Oakland, or Alameda—and for the manufacture and storage of buoys, many of which can be seen lying on the landing there. Strenuous efforts were made several years ago for the possession of this island by the Central Pacific Railroad Company, as the western terminus of their great overland road, and for the accommodation of vessels loading with wheat, wool, argentiferous ores, or other California products; but the property owners of San Francisco saw the mental mirage of a rival city looming up, and successfully opposed its cession. Now the ship-loading business, intended for Goat Island, is carried on at Long Wharf, northwesterly from the Oakland pier, where vessels from all nations can be seen taking in cargo, for their respective destinations. But the ring of the bell responded to impatiently, apparently, by the passengers gives intimation that we have crossed the Bay of San Francisco, and are at

The distance across, from the Market Street Wharf to the Oakland Pier, is three miles and sixty-three one hundredths, and has taken us just twenty minutes to accomplish it. Let us pause for a moment, if you please, and gaze at the hurrying stream of human life, flowing out from these commodious ferry-boats. If you and I could follow each and every one to his abiding place, enter into the secret heart-life of each and know their various plans and hopes, their sorrows, fears, and cares, I think our hearts would soften a little to the many. But, as we have to mix with the throng, or be left behind, we naturally cut short our reveries and walk ashore. Now a clear stentorian voice announces: “Passengers for Benicia, Sacramento, Stockton, Lathrop, and all intermediate points, please to step this way,” and we flow with the outward-bound tide of humanity into the capacious depot, where there seems to be a bewildering number of trains, for all sorts of places; but as the destination of each is announced in large letters, “so that he who runneth can read,” there is no danger of our selecting the wrong one.

As our course when leaving the ferry-boat has been to the left, we may have unintentionally passed

Perhaps, without noticing it. This would be a regretable omission, as it is one of the most commodious, as well as most comfortable waiting-rooms, to be found in any country or clime; for as soon as it is entered by returning passengers, its spaciousness, and cheery brightness bespeak a cordial welcome that always impresses pleasantly. Photographs, paintings, and “live” advertisements make it fairly to glisten with sprightliness. But to our journey.

With the waters of the Bay on each side of us, we speed along rapidly over a solid road-bed of rock, made through the shallow stretches of the Bay, instead of on piles and beams, as formerly, adding materially to the safety of the transit over it; the outlook broadening, and the interest deepening, as we advance.

There is something very exhilarating about the excitements of a journey through an unfamiliar country, and as soon as we have taken our seat in the railway car, and object after object, or scene after scene, opens up before us, we long for some one at our elbow, or by our side, to answer questions. This gratification is not always attainable. But, partly in anticipation of your wishes, it may be well to explain them briefly as we roll comfortably along. And, by way of commencement, when the cars stop at any particular station, as the conductor may be busy with his duties, and as you may like to know just how far we have traveled, the following table will explain the distances between San Francisco and Lathrop.—

| |

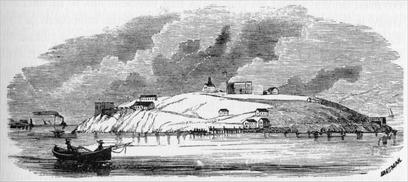

| Photo by S. C. Walker | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| The Yo Semite Fall—Cho-lock—During High Water. | |

| With “reflections." | |

| WAY STATIONS. | DISTANCES IN MILES. | ||

| Between Consecutive Points. |

From San Fran- cisco. |

From Lathrop. |

|

| By Railway

From San Francisco to— |

94.34 | ||

| Oakland Pier | 3.69 | 3.69 | 90.65 |

| West Oakland | 2.20 | 5.89 | 88.45 |

| Sixteenth Street, Oakland | 0.60 | 6.49 | 87.85 |

| Stock Yards | 2.26 | 8.75 | 85.59 |

| West Berkeley | 1.67 | 10.42 | 83.92 |

| Highland | 1.26 | 11.68 | 82.66 |

| Point Isabel | 1.09 | 12.77 | 81.57 |

| Stege | 1.15 | 13.92 | 80.12 |

| Barrett | 2.20 | 16.12 | 78.20 |

| San Pablo | 1.47 | 17.59 | 76.75 |

| Sobrante | 3.23 | 20.82 | 73.52 |

| Pinole | 3.20 | 24.02 | 70.32 |

| Tormey | 2.74 | 26.76 | 67.58 |

| VALLEJO JUNCTION | 2.25 | 29.01 | 65.33 |

| Valona | 0.61 | 29.62 | 64.72 |

| PORT COSTA | 2.55 | 32.17 | 62.17 |

| Martinez | 3.47 | 35.64 | 58.70 |

| Avon | 3.51 | 39.15 | 55.19 |

| Bay Point | 3.09 | 42.24 | 52.10 |

| McAvoy | 3.26 | 45.50 | 48.84 |

| Cornwall | 4.39 | 49.89 | 44.45 |

| Antioch | 4.65 | 54.54 | 39.80 |

| Brentwood | 8.16 | 62.70 | 31.64 |

| Byron | 5.13 | 67.83 | 26.51 |

| Bethany | 8.81 | 76.64 | 17.70 |

| TRACY | 6.61 | 83.25 | 11.09 |

| Banta | 3.09 | 86.34 | 8.00 |

| LATHROP | 8.00 | 94.34 | |

| Total from San Francisco to Lathrop | 94.34 | ||

On, on we ride, past the western suburbs of Oakland, the Stock Yards, and West Berkeley, various manufacturing establishments, catching a hasty glimpse of the California University buildings, the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Asylum, and other State institutions, standing among the gently rolling foot-hills of the Contra Costa Range, the distance for many miles out being dotted with comfortable residences or prosperous farms. Back of and east of these rise the green yet almost treeless ridges of the Contra Costa Hills, covered to their summits in spring and early summer with a luxuriant growth of wild oats, which, in the fall, change to a rich golden brown, from very dryness.

In early days, owing to carelessness, or to wantonness, miles of this parched surface would be ignited, and fire sweep over it in rolling waves, throwing its lurid light both far and near, and burning everything that was combustible—the wild oats included. Fortunately, however, nature had provided each grain with two slender extremities, as though anticipating the coming danger; and as the oats dropped down upon the ground, and became swollen by the dews of night, those extremities were contracted inwards towards the body of the grain, when their feet inserted themselves into the ground; the next day’s warmth dried out the moisture, and in so doing straightened out the legs, so that by this process the grain itself was forced forward, until it dropped into one of the many sun-cracks near, and was entirely out of danger from the destroying element. The first heavy rains following, swell the earth sufficiently to cover the wild oats entirely up; when they stool out from among their hiding-places in the cracks; and when the tender shoots make their appearance, the whole surface presents a resemblance to some grotesquely woven, tessellated carpet.

Moving rapidly forward, and shooting past some stations without stopping, our course, for nearly thirty miles, lies along the southeastern margin of the charming bays of San Francisco and San Pablo; the light glinting upon their waters, and beyond which are the purple hills looming up in picturesque irregularity, indicating numerous spurs, or starting points of apparently different ranges, until we pass the Starr Co.’s flouring mills (where some two thousand five hundred barrels of flour are said to be manufactured daily) and arrive at Vallejo Junction. Now we lose those of our fellow-passengers who are bound for Vallejo, the Government works of Mare Island, Napa, and other prosperous settlements in these midland valleys.

Three miles farther on—the intermediate distance occupied mainly by grain warehouses and workshops—we reach the famous ferry landing of Port Costa, where all Eastern-bound passengers leave us for their multifarious destinations. Here we find

This plies between Port Costa and Benicia, across the Straits of Carquinez, the distance between the slips being within a few feet of one mile. As this is the largest boat of her class afloat, the following description, kindly furnished by its owners, will be found interesting:—

The dimensions of the double-ender transfer boat Solano are: Length over all, 424 feet; length on bottom, 406 feet; height of sides, at center, 18 feet 5 inches; at ends, from bottom of boat, 15 feet 10 inches; moulded beam, 64 feet; extreme width over guards, 116 feet; camber, or reverse shear of deck, 2 feet 6 inches. Draught, light, 5 feet; loaded, 6 feet 6 inches. Registered tonnage, 3,541 31—100 tons.

She has two vertical beam engines: Cylinders, 60-inch bore, 11 feet stroke; wheels, 30 feet diameter, with 24 buckets each, 17 feet face.

Engines are driven by 8 steel boilers, each 28 feet long, 7 feet diameter of shells, containing 143 tubes, 4 inches diameter by 16 feet long. Total heating surface in 8 boilers, 19,640 square feet; grate surface 288 square feet, capable of driving engines with 2,000 horse-power each. The boilers are placed in pairs, on the guards, forward and abaft the paddle boxes, connected with engines, so that one or all may be used at pleasure.

The engines are placed on the center line of the boat, fore and aft of the center of boat, 8 feet, making distance from center to center of shafts 16 feet, and not placed abreast of each other, as in the usual manner. The object of this arrangement is to give room on deck for four tracks—and each wheel being driven by an independent engine, enables the boat to be more easily handled in entering slips.

Among other novelties in her construction are four Pratt trusses, arranged fore and aft, directly under tracks, varied in size to meet the strains upon them. These give longitudinal stiffness, and connect the deck and bottom of the boat, making her in reality a huge floating bridge. In addition there are eleven water-tight transverse bulkheads, dividing the hull into twelve compartments, rendering her absolutely secure from all danger of sinking, besides adding additional stiffness to the boat.

There are four balanced rudders at each end of boat, 11½ feet long by 5½ feet deep, coupled together and worked by hydraulic steering gear, operated by independent steam-engines and pumps. The steering gear is connected also with steering wheels in the ordinary manner—the pilot houses being 40 feet above deck, affording the helmsman a clear view, fore and aft.

There are four bridges running athwartship, and another fore and aft, connecting the pilot houses. Upon the deck are four tracks extending the entire length, with capacity for 48 freight cars, with locomotive, or 24 passenger coaches of the largest class.

The aprons connecting the boat with the slips at Benicia and Port Costa are each 100 feet long, with four tracks, so arranged so that freight and passenger trains are run aboard without being uncoupled from the locomotive. The aprons weigh, each, 150 tons, and are worked by a combination of pontoons and counter-weights, by hydraulic power.

In the hold of the boat are commodious quarters for the officers and crew; on deck, rooms for the transaction of railroad business.

These form the only outlet for the entire water-shed of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and the great basins of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, with their tributaries, comprising an area of nearly thirty thousand square miles. This, therefore, from necessity, forms the only inland, Golden Gate-like entrance, for all vessels needed for the commercial wants of the interior, outside and apart from the out-reaching railroad system of the State.

Instead of crossing the Straits of Carquinez, however, we continue along its southern shore for some distance yet; and in about three miles arrive at Martinez, the county seat of Contra Costa County. This, believe me, is one of the prettiest agricultural villages in any country. A week among its vineyards, gardens, groves, and farms, will convince the most skeptical of this.

|

| COUNTRY NEAR MARTINEZ. |

Here, too, the beautiful live oak (Quercus agrifolia) and the gracefully drooping white oak (Q. lobata) add their inviting attractions to the landscape. This, moreover, is the avenue by which Pacheco and other valleys are reached, and where the native Californians in early days enjoyed so many pastimes; which, like many of its people, have passed away forever. On this account I am tempted to briefly chronicle some of the most

Like their Mexican prototypes, they are very fond of amusements. They can endure any amount of enjoyment in every form, and at all times, and take as kindly to pleasure as though they were born to it. There is also another sympathetic characteristic between the two peoples—neither of them will do anything today in the form of work that they can, by any possibility, postpone until to-morrow. Mañana esta siempre buena (to-morrow is always good), where labor is concerned, because it never comes. On these accounts, mainly, every “saint’s day,” among these old settlers, was welcomed, because it brought a holiday.

It used to be an interesting sight to watch these dusky-colored people issue from their humble, tile-roofed, adobe dwellings, in any of their dreamy towns, at sunrise, on any favorite saint’s day, when the matin bell called to prayers. Then the señoritas and señoras, dressed in the brightest of colors; and the señores begirt them selves in the gayest of sashes; and all walked, saunteringly, side by side, to the shadow-filled house of devotion where, with low musical chantings, solemn ceremonials (and equally solemn countenances) they knelt together in seeming worship.

But no sooner was the church threshold recrossed than they felt “A change came o’er the spirit of my dream"’ that almost amounted to an entire transformation; the muttered response was eversed to a merry laugh, and the kneeling posture to a lively, light-footed skip. Now the arrangements for the day’s enjoyments were freely discussed, and every preparation made for insuring a general holiday. Wayside stalls, laden with fruits, cakes, sweet-meats, toys, and general refreshments, would spring up here and there; and be well patronized by juveniles, and friends that had come in from the neighboring ranches.

|

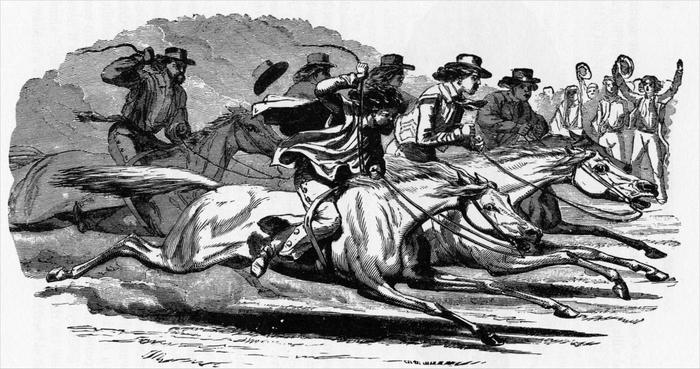

| NATIVE CALIFORNIANS RACING. |

Every native Californian is as much at home on a horse, with or without a saddle, as a Sandwich Islander is upon a surf-board when he plays upon the waves; and, as horses are their particular pride (even while they excessively abuse them when in passion), skill in riding is the most esteemed of all accomplishments. Associated with this, and of which it forms a part, is the love of display; so that next to a beautiful animal the most costly of caparisons are preferred. A native Californian will, therefore, invest his last real (and go hungry) rather than forego the indulgence of expensive ornaments for his saddle, bridle, and spurs. And as horse-racing strikingly provides him with the opportunity for exhibiting these to the best advantage before the fair sex, and his envious companions, he indulges it to infatuation. Scarcely secondary to this, and for the selfsame reasons, follows the popular pastime of “snatching the rooster.”

|

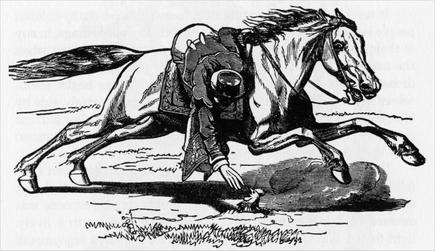

| NATIVE CALIFORNIAN, WHEN AT FULL SPEED, SNATCHING THE ROOSTER. |

As illustrated in the above engraving the body of the rooster is buried, so that nothing but the head is visible above ground. All of those who are mounted, and whose horses are prancing and dancing, about sixty yards distant, are to take part in the sport, and are impatiently awaiting their turn. The moment the signal is given for the start, the impetuous and expectant rider sets spurs to his horse, and dashes out at the top of his speed; and, when nearly opposite the would-be prize, he makes a dexterous swoop down to it; and, if he succeeds in clutching and unearthing the bird, he bears off the trophy in triumph, amid the applause of the concourse assembled. But, should he fail in the effort, as most frequently happens, he not only loses the favors he had looked forward to winning, but sometimes is unhorsed with violence, and dragged in the dust, at the risk of serious accident; and that, too, amid the derisive jeers and laughter of the spectators. Valuable horses, with their costly trappings, and sometimes large sums of money, and even ranches, are not infrequently staked upon the issue of “snatching the rooster.”

Another source of amusement among native Californians, and this also was intended to illustrate their dexterity in horsemanship, is to place a rawhide flat upon the ground; and, when the horse is galloping swiftly, to suddenly check him in the moment his forefeet strike the hide. If, by any possibility, the horse is allowed to cross this before stopping, the rider is berated most unmercifully for his lack of skill, especially if he should be unseated in the effort. But the greatest of all sources of gratification, to all classes and to both sexes, were the

After the discovery of gold, and before their grounds were acquired and much settled up by Americans, these people took increased delight in the cruel and dangerous recreation of bull-baiting, and bull and bear fighting, until 1852, when it was frowned down by the public, and prevented by the authorities. On one occasion thousands of persons had collected, in one of our populous valleys, to witness one of these disgraceful exhibitions, when twelve bulls, two large grizzly bears, and a considerable number of Indians were engaged at different times. In the second day’s encounter four Indians and one horse were killed; and while the sharp horns of the infuriated bull were goring their voluntary victims, the band would strike up a lively tune to smother their cries and moans. Fortunately these, with cock-fighting and other debasing amusements, have, let us hope, forever ended, as they have been superseded by those which are progressive and refining.

The native Californians, with their half-dreamy and semi religious teachings, seemed to have been a compromise between barbarism on the one hand and the aesthetical refinement of progress on the other; and, owing to their easy, “go-as-you-please” temperaments, and manners, have been despoiled, and sharply elbowed off the track in the great race of life, with a few tenacious and plucky exceptions; and, with their customs, for the most part, been retired into the irretrievable past.

Leaving the county seat of Contra Costa behind us, with the rolling hills that surround it, we emerge into an open country studded with farms that skirt the base of an imposing mountain on our right, known to the world as

Whether we are walking on the streets of San Francisco, or sailing on our bays and navigable rivers, or riding on the roads in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys, or standing on the elevated ridges of the Sierras; in lonely boldness, at almost every turn, Monte Diablo stands prominently out as the great landmark of Central California.

Viewed from the northwest or southeast, it appears to have a double crown, with two elevated crests that are about three miles apart. The southwestern is the higher, with an elevation of three thousand eight hundred and fifty feet above sea level. From this lofty standpoint the country is spread out before you like an immense map, covering an estimated area of forty thousand square miles of land, and forming one of the most remarkable panoramas ever viewed by human eyes. To describe this in detail would of itself fill a volume. It is presumed that its name-givers, the early padres, having climbed it, and looked around upon its unspeakable wonders with awe, recalled to memory that passage of holy writ from Matt. 4: 8, 9: “The devil taketh him [Jesus] up into an exceeding high mountain, and sheweth him all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them; and saith unto him, All these things will I give thee, if thou wilt fall down and worship me,” and that this suggested the name. Without even attempting an outline of the glorious view presented, let me counsel you to pay the summit of Monte del Diablo a visit, if you wish to revel in a scenic banquet, the memory of which will remain with you pleasantly forever. To accomplish this you leave the train at Martinez, and proceed to Clayton; whence you can ride to the very summit, by a fairly good road, and back again to Clayton, in a single day.

For the purpose of surveying the State into a network of township lines, three “meridians,” or initial points, were established by the United States Survey, namely: Monte Diablo (Contra Costa County), Mount San Bernardino (San Bernardino County), and Mount Pierce (Humboldt County). Across the highest peaks of each of these a “meridian line” and a “base line” were run; the latter being from east to west, and the former from north to south. Of these three the Monte Diablo is by far the most comprehensive, as it includes all the lands lying between the Coast Range and the Sierras, and from the Siskiyou Mountains to the head of the Tulare Valley.

The geologic features of Monte Diablo are mainly primitive, although surrounded by sedimentary rock, abounding in marine shells. Near its summit gold-bearing quartz has been found in veins; on its western slope hornblende; and, in its numerous spurs, an inexhaustible supply of limestone. It is said that both copper and cinnabar ore has been found here, but with what truthfulness has not been determined. At the eastern base of Monte Diablo several veins of coal have been found, but this being strongly impregnated with sulphur, has been used, principally, for steamboats.

The cañons of this mountain are lined with stunted oak, and pines; and wild oats and chaparral, alternately, grow from base to summit. In the fall season, when the herbage and dead bushes are perfectly dry, the Indians have sometimes set portions of the surface on fire, and when the breeze is fresh, and the night dark, the lurid flames leap, and curl, and sweep, now to this side and now to that, and present a spectacle magnificent beyond the power of language to express.

But as time forbids a longer tarrying here, for the present at least, let us ride onward past farms, with cattle and horses on either side of the track; shoot under tramways from the Monte Diablo coal mines at Cornwall and Antioch; and, before long, arrive at Tracy, where the Western Division of the Central Pacific Railroad forms a junction with the main line. But a short time will elapse before crossing the San Joaquin River (which obtains its waters from the living glaciers of Mount Ritter, the Minarets, and other lofty peaks of the main chain of the Sierra Nevada Mountains) and, continuing about three miles beyond, we arrive at

Here the trunk, or main line, forms a junction with its diverging branches, both north and south. This station—named in honor of Mrs. Leland Stanford (wife of Governor, now United States Senator Stanford, one of the founders and builders of the Central Pacific Railroad, and continuously its president) whose maiden name was Lathrop—from its establishment, has always been a general stopping-place for refreshments; and, when approaching it, you will still hear some resonant voice announce, “Lathrop—twenty minutes for meals.” In recent years an opposition gong has rung out its unmusical clang, to tell to the hungry that there are other places at Lathrop, besides the station, where the hungry can be fed. Here, also, are workshops, engine houses, surplus cars, and all the usual paraphernalia of a central depot; so that “extras” of every kind needed in railroad transportation can be furnished without the least unnecessary delay. Railway officers, with their assistants, naturally make this quite a lively station; and, when the trains arrive with their passengers, all is bustle and excitement. Within the past few years this has grown somewhat into an agricultural settlement, which, with the conveniences needed by railway employes, has changed its formerly sleepy and forsaken look to one of wide-awake business prosperity, that augurs well for its future development and advancement.

If we are bound for Yo Semite via Modesto, Merced, Berenda, or Madera, we keep our seats in the car; but, if our ticket provides for entering the great Valley via Stockton, Milton, and the Calaveras Big Trees, or Milton direct, we change both ourselves and our baggage to the Stockton train. For particulars concerning routes beyond Lathrop, the reader is referred to one or other of succeeding chapters so that he may obtain the information desired on the one he has decided to take.

Next: Chapter 15 • Index • Previous: Chapter 13

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/14.html