| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Bay & River Routes >

Next: Chapter 16 • Index • Previous: Chapter 14

|

Breathe soft, ye winds! ye waves, in silence sleep.

—Gay.

|

|

You know I say

Just what I think, and nothing more or less, And, when I pray, my heart is in my prayer. I cannot say one thing and mean another: If I can’t pray, I will not make believe!

—Longfellow’s

Christus, Pt. III.

|

|

The fall of waters and the song of birds,

And hills that echo to the distant herds, Are luxuries excelling all the glare The world can boast, and her chief favorites share.

—Cowper’s

Retirement.

|

About two hundred yards northerly of the Market Street Wharf lies that of Washington Street, whence sail the San Joaquin River steamboats bound for Stockton, on the Milton, Calaveras Big Tree, and Big Oak Flat routes to Yo Semite, with other destinations. If the freight is all aboard, they sail at five o’clock p. m.; but, if not, they generally delay starting until it is. As at the Market Street Wharf, the scene here is full of excitement, and of positive interest, although not partaking, altogether, of the same characteristics. The former is quiet and methodical; while this is irregular, and somewhat contentious; owing to the established rivalry between the two lines. Each has its friends; and both employ their own advocates. Eagerness to possess passengers, at any cost of eloquence, or of tact, is of more momentous consideration, at this juncture, than any rules of ordinary courtesy, or of personal convenience. But, once on board either of the boats, you are safely delivered from that vortex of contention, and peace reigns supreme. Polite attention places you entirely at your ease; and, if the war of words is still raging below, it only becomes a source of amusement, to beguile the otherwise wearying moments of waiting. This, however, is of short duration, as orders are soon given by the captain to “Take in the plank,” “Cast off your lines;” and, just as we are about to move out from the wharf, there is almost sure to be one or more passengers that have arrived, just too late to get aboard; and who, in their excitement, often throw their overcoat, or valise, or other articles on the boat (or overboard), yet neglect the only opportune moment of getting on themselves; and, consequently, are not only left behind, but are separated from their baggage; and which, perhaps, contains the only treasures they possess on earth! Not inconsiderately of this, let us hope,

Who, at such a season, does not recall the peaceful calm that uninvitedly steals over the spirit the very moment the boat has cast off her moorings, and sails out upon the placid waters of the Bay? All of the fatigues and wearying cares of the few last hours ashore—and something, kept to the last, is almost sure to go unaccomplished—are left, with it, behind; and, for the time being at least, are merged into absolute forgetfulness. Now comes the season of bewitching, perfect, unrestrained composure, as calm as the brine over which we are gliding. At such a befitting time for impressions, and mood for enjoyment, every object presenting itself reveals to us an exalted interpretation. The golden sheen of the setting sun, as it lights up the pathway of commerce through the Golden Gate, seems brighter and more golden as we pass it. Even the fog-banks that sometimes roll through the Golden Gate, in summer, have silvery edges; and the haze that drapes each mountain height, or dreamily sleeps in far-off cañons, is of a more ethereal purple when we thus preparedly commune with nature’s mysterious wonders. Now we are sailing past, let us take

There is a peculiarly seductive charm that stealthily yet feelingly carries one into the far dreamy past, as he looks upon this scene; and recalls old-time memories, when this was almost the only entrance to the land of gold. How revertingly the sight again brings into review the golden-winged hopes, and heart-throbbing yearnings of the many who entered, or wished to enter, its charmed portals, “in days of auld lang syne,” and make it the admission gate to fame and fortune; but who, perhaps, after coming through it, spent years of unremitting and unrequited toil; and yet hoped, aye, longed, to pass through it once again, to that place still endearingly called “home"—

“That spot of earth, by love supremely blest,

A dearer, sweeter spot, than all the rest.”

With a chastened sadness in the heart, because they had hoped and yearned in vain. But to those whom success had crowned with its exhilarating laurels, how exultingly—and let us hope gratefully—welcome was their homeward passage through the Golden Gate; to share their fortunes with beloved ones, who, perhaps, had long been expectantly awaiting their return. Many have supposed that the origin and meaning of the name given to this entrance to the Bay of San Francisco was suggested by the staple mineral of the country, gold. This is an error, as it was called “The Golden Gate” before the precious metal was discovered. It was probably used for the first time in a work entitled “A Geographical Review of California,” by Col. J. C. Fremont, published, with a map, in New York, February, 1848; and as gold was discovered on the 19th of January preceding, the news could not have reached the office of publication, in those days, in time to influence this nomenclature. It is true there “may have been” some “spiritual telegrams” (!) sent to the author of the name, Col. J. C. Fremont, telling him of the glorious dawn of a golden day that had broken upon the world by the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, Coloma, and thus become suggestive of the golden age, about to be inaugurated, and of the name. Its real origin was owing to the excessively productive lands of the interior, especially those around the Bay of San Francisco. From whatever source the name “Golden Gate” has sprung, its characteristic appropriateness will be unhesitatingly

|

| PASSING THE GOLDEN GATE. |

The Golden Gate, then, is the only entrance by sea to the land-locked and magnificent harbor of San Francisco. It is situated in the narrowest part of the channel, between Fort Point and Lime Point. Its width is one thousand, seven hundred and seventy-seven yards. Here the tide ebbs and flows at the rate of about six knots an hour, and rises or falls some seven feet. The center of the Gate is in longitude 122°30’ from Greenwich. Through this flows the drainage of all the rivers from the High Sierra, entering the valleys of the Sacramento and San Joaquin, as well as from several tributaries of the Coast Range. It has depth sufficient to float, safely, ships of the heaviest tonnage. Even the circular sand-bar at its entrance, seven miles in length, offers no obstacle to this, even at low tide; except, possibly, when the wind is blowing heavily from the northwest, west, or southeast; then it is scarcely safe for a vessel of the largest class to cross it at low tide. On the south side of the Golden Gate is Point Lobos (Wolves Point), from whence vessels at sea are signaled; and on the northern, Point Bonita, upon which is set a light-house; while opposite Lime Point stands the frowning fort, Winfield Scott.

|

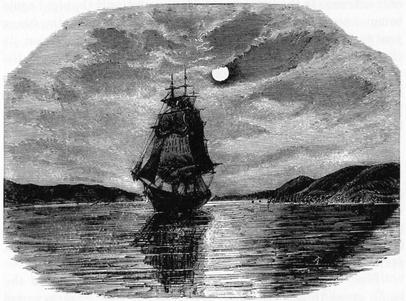

| THE FORT, NEAR VIEW. |

You can see by its grim and defiant presence that it means business, when the order comes to “let loose the dogs of war.” It is four tiers in height, the topmost of which is sixty-four feet above low tide, and is capable of mounting one hundred and fifty guns—including a battery on the hill at its back—of forty-two, sixty-four, and one hundred and twenty-eight pounders, besides rifled cannon of improved pattern. During an engagement, two thousand four hundred men can be accommodated here.

There is a light-house adjoining the Fort, that can be seen for some ten or twelve miles outside; connected with which is a fog-bell weighing eleven hundred pounds, that is worked by machinery, and strikes five consecutive taps ten seconds apart; then has an intermission of thirty-four seconds, when it re-commences the ten-second strike. This is carried on continuously in foggy weather.

At a convenient distance from Fort Point is the Presidio, which is the residence and head-quarters of both officers and men for this military district. Others are stationed at Point San Jose, formerly called Black Point. To outline these even, with their maneuverings, music, life, etc., would detain us too long; but it is hoped that this “mere mention” will induce you to pay each one of these a visit, to see and enjoy them at your leisure, upon your return.

But as the keel of our boat is speedily cutting its way through the water, we pass Alcatraz and Angel Islands; obtain glances of the snug little towns of Saucelito and San Rafael, catch a hasty sight of the State Prison at San Quentin; and, almost before we realize it, are opposite a gaudily stratified island known as

|

| RED OR “TREASURE” ROCK. |

This bright-colored little island was formerly called Treasure, and, in old charts, Golden Rock, from a traditionary report circulated that vast treasures had been buried there, by pirates and old Spanish navigators. Such stories were always sufficiently stimulating to induce the semi-demented adventurer, and dime novel reader, to attempt the securing of wealth with as little exercise as possible of his own. Hence the representative “treasure hunter” found occupation here, and, as elsewhere, went unrewarded for his pains.

It is now exclusively called “Red Rock,” being composed of numerous strata, of an endless variety of colors, the prevailing one being red. There is an article found here that strikingly resembles one sometimes found upon a lady’s toilet table (in early days, of course) known as rouge-powder (exclusively monopolized in these modern times by the theatrical profession). Besides this there are several veins of decomposed rock resembling clay, or pigment, from four to twelve inches in thickness, and from steel-gray to bright red in color. Upon the beach small red pebbles, resembling carnelian, are found in abundance. But on, on we sail; passing Maria Island, and

|

| THE TWO SISTERS. |

Both of which are covered with sea-birds, that seem to be tastefully and gracefully busy pluming their feathers; and who make this their roosting places at night, no matter where they may have wandered during the day.

Just beyond these we shoot by San Pablo Point (which juts out from the mainland) and enter the placid waters of the bay of San Pablo. The distant hills, with their lights and shadows, and varied verdure, encompassing us, are not less attractive upon water than on land for they seem to charm us into forgetfulness of the fact that, almost before we realize it, the hills are closing in upon us, and we are rapidly

|

| ENTERING THE STRAITS OF CARQUINEZ. |

When safely passing the narrowest part of the channel, we seem to be meeting “the leviathan of the deep,” or some other huge monster that is coming down fearlessly upon us, and is about to swallow us up, as Jonah swallowed the whale (?); but just as we might suppose it to be opening its immense mouth for one easy effort, it shoots to one side (as we do to the other) as much as to say, “You needn’t be afraid of me, I am only the C. P. R. R. transit boat Solano, on my way from Benicia to Port Costa!”

|

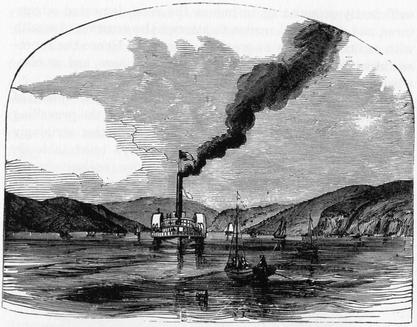

| LOOKING TOWARD THE SACRAMENTO RIVER. |

This, with its numerous islands (almost level with the surface at high water), is nearly as large as the bay of San Pablo. At one time, “in the uninterpretable past,” it must have resembled a small inland sea, inasmuch as the broad expanse of the tule lands, now covering several thousands of square miles, once formed a portion of the bay. An apparently interminable sea of tules extends nearly one hundred and fifty miles northeasterly up the valley of the Sacramento, and for more than half that distance southerly, up the valley of the San Joaquin, with an average width of thirty miles; and as nearly all of this land is overflowed during high water there can be but little doubt of its once having formed an immense lake.

|

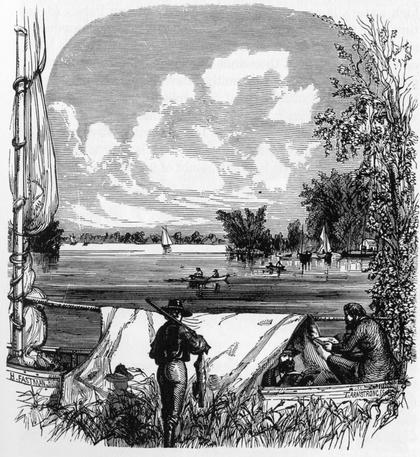

| SALMON FISHING—PAYING OUT THE SEINE. |

Deriving its main source from the living glaciers of Mt. Ritter, the Minarets, and other lofty peaks of the High Sierra, whence it hurries rapidly to the plains, but runs sluggishly through these tules, and forms one of the most serpentine of all rivers out-of-doors. It is navigable for somewhat commodious steamboats and large schooners to Stockton, and some seventy miles beyond for smaller craft. It makes its debouchure into the bay of Suisun just above Cornwall and Antioch, landings for the Monte Diablo coal mines.

|

| SALMON FISHING—HAULING IN THE SEINE. |

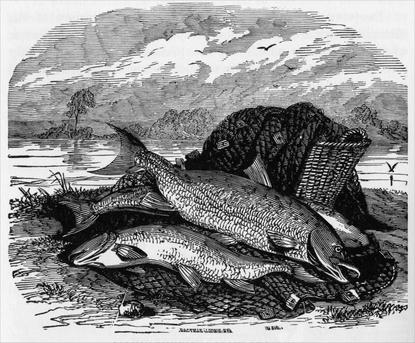

Were we passing this earlier in the day, the scene would possibly be enlivened by the sight of sundry small boats, and men engaged in salmon fishing, which still forms quite an important industry here, and at the junction of the Sacramento River with the Bay of Suisun; interesting, however, as it might be to linger here, and watch the modus operandi of taking in this valuable fish, we must now forego it.

|

| SALMON FISHING—A GROUP OF SALMON. |

After touching at the latter settlements for the disembarkation of passengers and cargo, we are soon sailing upon the turbid waters of the San Joaquin. But for the overshadowing mountain of Monte Diablo, whose omnipresence still asserts itself here as elsewhere, the scenery would prove to be very uninteresting. But, as the evening is calm (and sultry, perhaps) the mosquitoes may offer a little divertisement; as, possibly, this may be their harvest season; and, as a consequence, a large representation may be out, on a free-booting excursion. Now, although their harvest—home song may be very musical to those who can enjoy its feeling refrain, it becomes penetratingly evident to any disinterested observer, that but few persons on board seem to have an appreciative ear for their music! In order, however, to show that they have no idea of being overlooked, or neglected, the mosquitoes take real pleasure in impressing their embossed notes upon the hands, faces, or foreheads of all unwatchful sleepers—even though their slumbers may have been involuntary from exhaustion, or in combating their musical enemies. While this unequal warfare is going on, and for one carcass slain a dozen mourners come to the funeral, we may as well do something more than fight these little bill-presenting, tax-collecting tormentors; so, please permit me to relate an incident that occurred, just as I was leaving my Southern home, on the banks of the “Father of waters,” the old Mississippi, in the spring of 1849:—

A gentleman arrived from “Merry England,” with excellent letters of introduction, and was at once admitted a member of our family circle. Now, however strange it may appear, this gentleman had never looked upon a live mosquito—there being no such insect in England—and as a sequence was as unfamiliar with a mosquito-net and its uses, as the average office-holder might be with politeness. The femme de charge being unaware of this, had omitted to call his attention to the arrangements there for passing a comfortable night. In the morning, when he presented himself at the breakfast-table, his face was nearly covered with wounds from the enemy’s proboscis; without seemingly noticing this, the lady of the house politely inquired if he had slept pleasantly; “Ye-yes,” he replied with some hesitation “ye-yes, tol-er-a-bly pleasant, the bed was sufficiently comfortable, but, a—a—small—fly annoyed me somewhat.” At this confession the assembled company could not refrain from a good hearty laugh, in which the English gentleman most cordially joined, although it was at his expense. The good-natured hostess, after duly suppressing her risibility, explained the uses and arrangements of the mosquito-bar, to insure comfort in mosquito-infested countries, to the entire satisfaction of her guest. But the small fly was a source of considerable mirthfulness in our social circles there for a long time afterwards.

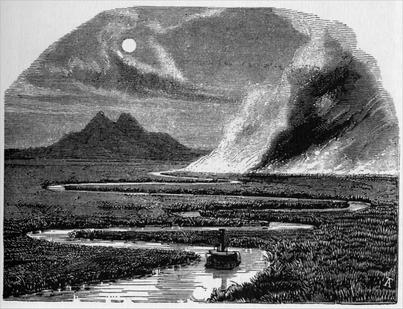

“Boxing the compass” in every conceivable direction, on a sea of tules; stopping here and slowing there, to avoid a jutting point of tules, or compass a bend of the circuitous river, upon which we are supposed to be sailing; our attention is attracted by a bright light in the distance, accompanied by the startling information that

To those who are unfamiliar with the water-plant, well known in California as the tule, or, more generally called, tules, a briefly outlined sketch may not be unacceptable, especially as the word is not to be found in “Worcester,” or in “Webster Unabridged.” Its botanical name is Scirpus palustris, var. Californica. In form and habit it resembles the eastern flag, with this difference; the flag is flat, while the tule is round for two-thirds of its height, tapering to a point, and flattening as it tapers, like a sailor’s needle. Although perennial in character, its growth is annual, and from six to twelve feet. Owing to the inexhaustible quantities and the vast area covered by this plant, efforts have not been wanting to press it into useful service; for paper, encasing of bottles, life-preservers, underlying for carpets, etc., and, for life-preservers it is worth four to one of cork. This, when closely interwoven and stretched upon a frame, then covered with pitch, is said to make a boat as light as a bark canoe.

Let it be remembered that there are slightly elevated grounds, and islands, in this sea of tules, that they are not only inhabited, but which are susceptible of high cultivation; and are of marvelous productiveness, after the native plant is subdued; from three to four crops a year having been harvested therefrom. An intelligent gentleman, well known to the writer, reliably informed him that, while gathering one crop of wheat, yielding sixty-five bushels to the acre, a neighbor of his was just sowing the adjoining lands; and harvested his crop in sixty days thereafter! One cultivator has six thousand acres of potatoes in a patch, on Roberts’ Island. Most of the vegetables used in Stockton are procured from the tule lands. But from the uncertainties and dangers of occasional high water, these tule lands would become exceedingly valuable—and will be when a thoroughly efficient system of leveeing and drainage are adopted.

And let us, if you please, suppose that a flood-proof protective levee has been constructed around two hundred thousand acres of this productive land; with drains, waste-gates, and every other contrivance to insure its being thoroughly done, at an estimated cost of $20,000,000. Then let us, if you please, suppose that this area has been put into successful cultivation, and will yield sixty-five bushels to the acre, the total product for a single crop (and two can be easily raised) would be thirteen million bushels; which, at the low estimate of sixty cents per bushel, would aggregate $7,800,000 annually, and of course would double that amount should two crops be realized.

But, while we have been talking, our steamboat has been drawing nearer and nearer to the conflagration, so that we can see the broad sheet of devouring blaze leaping into the air, and with tongue of flame licking up everything that is combustible, like a prairie on fire; and which, with the black smoke surging hither and thither, its edges and masses covered with a lurid

|

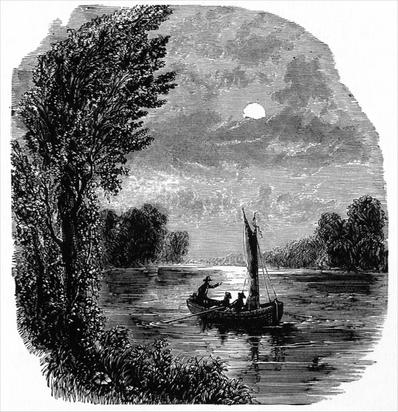

| THE SAN JOAQUIN RIVER AT NIGHT—TULES ON FIRE. |

Whenever a dry season comes upon California the succulent pastures found here, by stock, supplies the needed forage. But as

|

| ENTERING THE STOCKTON SLOUGH. |

Next: Chapter 16 • Index • Previous: Chapter 14

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/15.html