| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Berenda Route >

Next: Chapter 19 • Index • Previous: Chapter 17

|

Go forth under the open sky, and list

To Nature’s teachings.

—Bryant’s

Thanatopsis.

|

|

O what a glory doth this world put on

For him who, with a fervent heart, goes forth Under the bright and glorious sky, and looks On duties well performed, and days well spent!

—Longfellow’s

Autumn.

|

Spinning out from the Lathrop depot on our way to Berenda, by the Southern Pacific Railroad, that being the route we have now elected to take, our course lies up the valley of the San Joaquin; past farms, and stock, and towns; with the snow-capped Sierras on our left hand, the Coast Range on our right, and both in the far-away distance until we reach Berenda. Here we leave the Southern Pacific and take the Yo Semite branch railroad to Raymond, twenty-two miles distant.

Our course lies easterly; and, for the first eight or ten miles, over a treeless tract of country, of the peculiar formation designated by people generally as “hog wallows;” consisting of little flat hills, nearly round, about twenty feet in diameter, and from one to three feet in elevation, only divided from each other by narrow hollows. As there are hundreds of square miles of these, all sorts of theories upon their origin have been formulated, but none, as yet, satisfactorily so. Some think them the creations of an immense number of rodents; others, by shrubs around which the wind has carried soil, and left it; others, by the action of water; but, as all these know as much about their cause as we do, there is something left over for all to inquire into and think about. Uninviting, however, as these may at first sight appear, for agricultural purposes, as the land is comparatively cheap, easily reclaimed, and the soil productive, they are rapidly being taken up by colonies of settlers.

|

THE BERENDA ROUTE.

From San Francisco, via Lathrop, Merced, Berenda, Raymond, Grant’s Sulphur

|

|||||

| STATIONS. | Distances in Miles. | Altitude, in feet, above sea level. |

|||

| Between consecu- tive points. |

From San Fran- cisco. |

To San Francisco. |

|||

|

By Railway. |

.... | .... | 200.03 | ||

| From San Francisco to— | |||||

|

Lathrop, junction of the Southern Pacific with the

Central Pacific Railroad (b c) |

94.03 | 94.03 | 58.00 | 28 | |

| Merced, on Southern Pacific Railroad (b c) | 58.00 | 152.03 | 26.00 | 171 | |

| Berenda, on Southern Pacific Railroad (a b c d) | 26.00 | 178.03 | 22.00 | 280 | |

| Raymond, on Yosemite Branch Railroad (b c) | 22.00 | 200.03 | .... | 350 | |

|

By Carriage Road. | .... | 60.90 | |||

| From Raymond to— | |||||

| Gambetta Mines | 13.00 | 13.00 | 47.90 | 1,900 | |

| Crook’s Ranch | 4.50 | 17.50 | 43.40 | 1,800 | |

| Grant’s Sulphur Springs (b c d) | 5.50 | 23.00 | 37.90 | 2,850 | |

| Summit of Chow-chilla Mountain | 6.50 | 29.50 | 31.40 | 5,605 | |

| Wawona (Clark’s)* (a b c d) | 4.50 | 34.00 | 26.90 | 3,925 | |

| Eleven Mile Station (b c) | 10.76 | 44.76 | 16.14 | 5,567 | |

| Chinquapin Flat (d) | 2.20 | 46.96 | 13.94 | 5,908 | |

| El Capitan Bridge, Yo Semite Valley | 10.31 | 57.27 | 3.63 | 3,926 | |

| Leidig’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley | 2.56 | 59.83 | 1.07 | .... | |

| Cook’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 0.30 | 60.13 | 0.77 | .... | |

| Barnard’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | .77 | 60.90 | .... | 3,934 | |

|

*From Big Tree Station (Clark’s) to and through the Mariposa Big Trees and back to

Station, 17 miles. |

|||||

|

RECAPITULATION. |

|||||

| By railway | 200.03 miles. | ||||

| By carriage road | 60.90 ” | ||||

| To Big Tree Groves and return | 17.00 ” | ||||

| ————— | |||||

| Total distance | 277.93 miles. | ||||

Leaving the railroad at Raymond our road now winds around oak-studded ridges, or across flats and low knolls, which, in spring, are garnished with an endless variety of flowers and flowering shrubs. Of the former, from a single square yard, carefully measured off, a botanical enthusiast informed the writer that he picked over three thousand plants! Journeying over the same ground in the fall, nothing but a just and discriminating imagination could realize how beautifully these hills were then garnished.

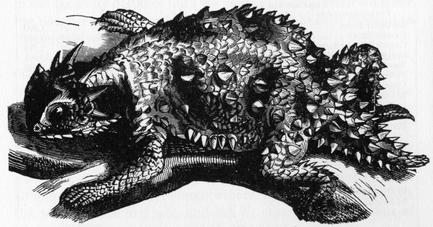

While changing horses at the station, there can sometimes be seen a horny-backed, and point-armored little reptile that attracts attention by the singularity of his appearance. It is called

This quaint little member of the lizard family is generally found on dry hills, or sandy plains; never in swamps or marshes. There are six different species, and all perfectly harmless. Owing to this, and their slow movements making them easy of capture, with their singular appearance, they have been carried off by curiosity-hunters, as pets; so that, although quite numerous some years ago, they are now becoming scarce. They possess the wonderful power of adapting their color to that of the soil; and change from one hue to another in from twenty-four to

|

| THE HORNED TOAD (Phrynosoma). |

When a resident of the mines, in 1849-50, the writer had a pair picketed out in front of his cabin for three over months; when, strange to say, at the end of that time, the male, which was the smaller of the two, wound himself around his picket-pin one morning, and strangled himself; and, on the evening of the same day the female followed his suicidal example. Upon making a post-mortem examination of the latter, a cluster of fifteen eggs

|

| EGGS OF THE HORNED TOAD, NATURAL SIZE. |

As we keep ascending, the scenery becomes more picturesque, and the shrubs and trees more interesting. There are two of the former that are very marked in their attractiveness: one is the “Leatherwood,” Fremontia Californica, which is from eight to twelve feet in height, covered with bright yellow blossoms; and the other the “Buckeye,” Aesculus Californica, having an erect panicle of pinkish-white blossoms, from six to twelve inches in height, and two or more in thickness. But were we to examine every flower, shrub, and tree, found upon our way, our task would be endless; as the late Dr. Torrey assured me that he saw over three hundred different species, not to mention varieties, in a single day’s ride, on his way to Yo Semite.

Just as we are coming to another station, the “lump-e-tump-thump” of machinery in motion tells us that we are near

That which is nearest the road, and most easily seen, is the “Shore Pride,” owned by J. M. McDonald & Bro. This is situated on “Grub Gulch” (the name of the post-office); so called from the fact that, whenever men grew too poor to exist elsewhere, they returned here, and “dug out a living.” To the left of this, and a little farther on, is the Haley or Gambetta Mine. This is a rich vein of ore that steadily yields a given sum (I must not tell you how much, as the amount was named confidentially; but it would take you and I many thousand years to starve to death upon it if we did not spend over $5,000 per month). If you wish to see a neat and cozy home, a well-arranged mill, and an excellent gold-bearing quartz ledge, do not fail to call here. These works are about thirty-three miles from Berenda, and are one thousand nine hundred feet above sea level.

But, threading our way among cultivated fields, over low hills covered with oaks and pines, we find ourselves at

Here you will find what New Englanders would call a “chipper,” brisk, go-ahead, wide-awake, and kindly-hearted man; who, as “mine host,” will make you feel at home; and, as proprietor, that he has spared neither money, time, nor energy to compel a forest-wilderness to “blossom as the rose.” He raises the largest crops, the biggest water-melons, the nicest strawberries, and the finest fruit to be found anywhere. More than this, he will praise his chicken, and chicken salad, or roast beef, or home-raised hams, and everything else upon his table; if for no other purpose than to help you to find an appetite to eat it. Almost before you know it, therefore, you find that you have not only eaten a hearty meal, but have thoroughly enjoyed it. If there could be found a single stingy hair in Judge Grant’s head, light as the crop is becoming, I believe he would pull it out.

Then, there are the “Sulphur Springs,” rolling out thirty-three inches of strong sulphurous water every second; and said to be fully equal to the celebrated springs of Arkansas, and Saratoga. These, with the mountain air, conveniences of access, and wildly picturesque surroundings, will bring hither many an invalid, who can here take out a new lease of life, with Judge Grant to assist in “drawing up the papers.”

Leaving this attractive spot, our road winds along the shoulders of Chow-chilla Mountain; and, while his bold brow of granite is frowning above us, there is a broad and marvelously beautiful landscape smiling below and beyond us, and one that it would be difficult to excel anywhere. Be sure and induce your coachman to “hold up” for a few moments to obtain this view.

That satisfying and intensely gratifying prospect only prepares us for the contrast so soon to follow; for, having reached the summit of Chow-chilla Mountain, and an altitude of five thousand six hundred feet, we enter a glorious forest of pines, which continues all the way down the mountain, some four and a half miles, to

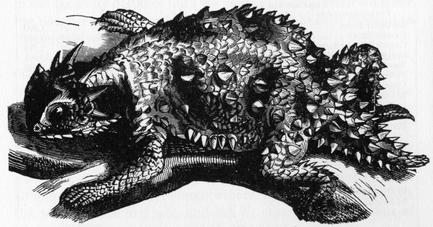

Wawona (the Indian name for Big Tree), formerly called “Clark’s,” is the great central stage station, where the Berenda, Madera, and Mariposa routes all come together; and which also forms the starting-point for the Mariposa Big Tree Groves. The very instant the bridge is crossed, on the way to the hotel, the whole place seems bristling with business, and business energy. Conveyances of all kinds, from a sulky to whole rows of passenger coaches, capable of carrying from one to eighteen or twenty persons each, at a load, come into sight. From some the horses are just being taken out, while others are being hitched up. Hay and grain wagons; freight teams coming and going; horses with or without harness; stables for a hundred animals; blacksmiths’ shops, carriage and paint shops, laundries and other buildings, look at us from as many different stand-points. That cozy-looking structure on our left is Mr. Thos. Hill’s studio; but that which now most claims our attention, and invites our sympathies, is the commodious and cheery, yet stately edifice in front known as the Wawona Hotel.

The moment we reach its platform, and are assisted in alighting by one of the three brothers, Mr. A. H., Mr. E. P., or Mr. J. S. Washburn, we feel at home. And while one or the other of these gentlemen are seeking to divest our garments of the little dust that has gathered on them, and the servants are performing a similar service to our baggage, let me introduce these gentlemen to you. Mr. A. H. Washburn is one of the principal owners of the Wawona Hotel, with its extensive grounds and pastures; and also of the Yo Semite Stage and Turnpike Company’s stage lines, of which he is the efficient superintendent. If he gives you his word for anything, you may rest assured that it will be accomplished, very near to programme, or proven to be utterly impossible. Mr. Edward Washburn, and Mr. John Washburn with his accomplished wife, will do their best to make our stay here enjoyable. To their kind and courteous care, therefore, we confidently commit ourselves.

After dinner the first place generally visited is

Here will be found quite a number of beautiful gems of art, the merits of which are assured from the fact that Mr. Thos. Hill took the first medal for landscape painting at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, and also the Temple Medal of the Academy of Fine Arts, of Philadelphia, for 1884, with numerous others. The paintings, therefore, will speak for themselves. We shall, moreover, find Mr. Hill a very genial gentleman, who has been everywhere, almost—if not a little beyond—seen about as much as most men, and can tell you what he has seen pleasantly, including his haps and mishaps. So that apart from the delight given by an inspection of his beautiful creations (and he loves Art for her own sake), our visit will meet with other rewards.

| |

| Drawn by T. Hill. | Moss Engraving Co., N. Y. |

| THE WAWONA HOTEL. | |

This, deservedly, forms one of the attractive pilgrimages around Wawona, and a sight of these botanical prodigies has probably been one of the many inducements to the journey hither. The trip is generally undertaken in the early afternoon; but, if time will allow, the entire day should be devoted to it. There is so much to be seen upon the way; its flora, and fauna (not much of the latter), and sundry “what nots,” that will otherwise beguile us into the regretful wish that we had more time to spend, lingeringly, among them. And, after all, what is time for, but to use well, and to spend pleasantly?

But before setting out for them, it may be well to state that this grove of big trees was discovered about the end of July, or the beginning of August, 1855, by a young man named Hogg; who passed by, however, without examining them. Relating the fact to Mr. Galen Clark and others, Mr. Clark and Mr. Milton Mann, in June, 1856, united forces, for the purpose of visiting and exploring the newly discovered grove; in order to definitely ascertain its location, with the number and size of its trees. These gentlemen, therefore, were the first to make known the extent and value of this new discovery. Finding that its position was near the southern edge of Mariposa County, it was thence-forward called the “Mariposa Grove of Big Trees.”

How renewing memory brings back the treasures of old-time experiences; when, in company with Mr. Galen Clark, three years later, we shouldered our rifles, carrying our blankets and provisions at the backs of our saddles, and started on my first jaunt to this grove, over the old Indian trail. How well and how pleasantly do I remember it, Mr. Clark; since which time you and I have both grown older, and learned many of the instructively suggestive lessons of life.

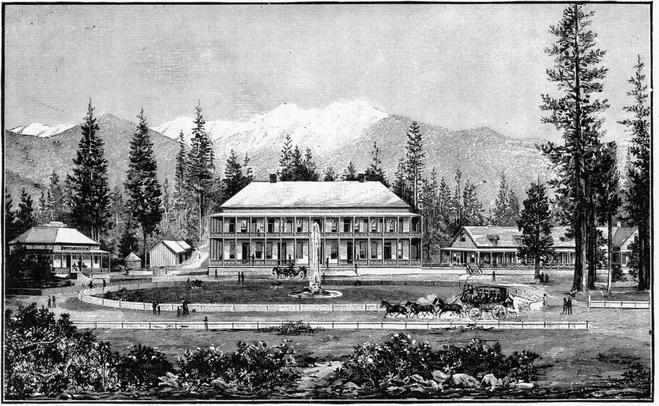

Is through a vast forest of stately pines, firs, and cedars, and among blossoming shrubs, and bright-faced flowers. On the way,

| |

| Sketched from Nature by G. Tirrel[l]. | |

| THE GRIZZLY GIANT. | |

And it looks at you as defiantly as the oldest veteran grizzly bear ever could. By careful measurement we found its dimensions to be, at the ground, including a jutting spur, ninety-one feet; and three feet six inches above the ground, seventy-four feet six inches. Professor Whitney places its circumference, eleven feet from the ground, at sixty-four feet three inches; with its two diameters at base thirty, and thirty-one feet; and, eleven feet above base, twenty feet.

But a mere statement of dimensions and altitudes of these trees can give no realizing sense of their idealistic presence and magnitude. It is the grandeur of their exalted individuality and awe-inspiring presence that thrills through the soul, and fills it with profound and speechless surprise and admiration; and not merely of one tree, but of whole vistas formed by their stately trunks. Who, then, by pen or pencil, can picture these as they are seen and felt? But we must not linger here, as there are just as many big trees in this grove as there are days in the year; so let us see a few of those which are most remarkable.

The coach generally halts at a large and deliciously cool spring near the cabin, where those who have come to spend the day will probably take lunch. Here, too, we shall have the pleasure of meeting the guardian of the grove, Mr. S. M. Cunningham, who knows every tree by heart; with its history, size, and name, and who can tell us more about them in ten minutes than many men could in an hour, who are perhaps quite as familiar with them, and he will do it cheerfully. I can see his bright and genial look, and can watch his wiry form and supple movements, while I write. There is one thing especially noticeable about Mr. Cunningham, he never gets discouraged; and always sees the bright side of things; so that when a storm is swaying the tops of the trees until they bend again, he can listen, interestedly, to their music; and can tell you laughable incidents until your sides shake.

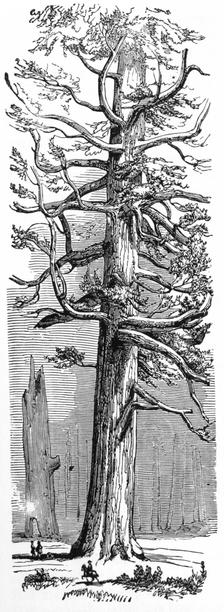

Two beautifully perfect Sequoias stand on either side the cabin, one named the “Ohio,” and the other “U. S. Grant.” The former is seventy-six feet in girth at the ground, and six feet above the ground is fifty-five feet; and the latter sixty-five feet six below, and forty-five feet above. Within thirty yards of these is the “General Lafayette,” thirty feet in diameter. Near this is the “Haverford” (named after the “Friends” College, Philadelphia), in which sixteen horses have stood at one time. It is burned into three compartments; across two of the spurs of which the distance is thirty-five feet; and, transversely, thirty-three feet. “Washington” has a girth of ninety-one feet, at the base; is round and very symmetrical. Although burned out somewhat near the ground, the new growth, as usual, is rapidly healing the wounds that fire has made. This is an especially excellent provision of nature for preserving and perpetuating this grand species, when in its prime; inasmuch as while restoring the ravages of the elements by the new growth, a much-needed support is added to the abutments, which intercepts and prevents its premature downfall.

The “Mariposa” is eighty-six feet in circumference, at the ground; and seven feet above it, is sixty-six feet. This tree seems to have been badly burned by two consuming fires, at different periods; after each of which the new growth has, visibly, at tempted its restoration. Near to this are four beautifully symmetrical trees, named, respectively, “Longfellow,” “Whittier,” “Lyell,” and “Dana,” a quarto of great natures, whose companionship is suggestive of poetry and geology going hand in hand with each other; and almost adjoining these is the “Harvard,” a tall and gracefully tapering tree of fine proportions, which seems to derive much strength of purpose from so congenial an association. The “Telescope” is an erect, burnt-out chimney-like trunk about one hundred and twenty feet in height, and which, although a mere shell, has still a growth of cone-bearing foliage upon it. The “Workshop” is an immense living giant with a capacious hollow at its base, which forms a room twelve by sixteen, in which all sorts of little souvenirs are made from broken pieces of the big tree.

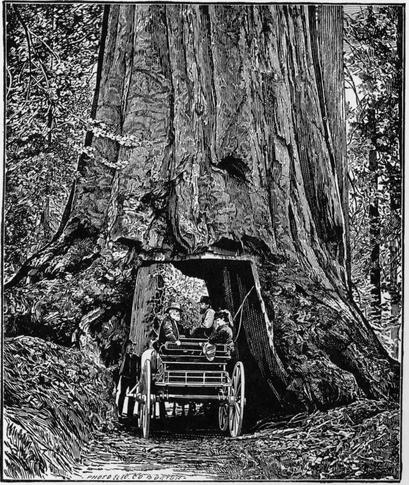

But, “Wawona,” the “Tunnel Tree,” through the heart of which the road passes, is one of the most attractive in the grove. At the base this tree is twenty-seven feet in diameter; while the enormous trunk through which the excavation is made is in solid heart-wood, where the concentric rings, indicating its annual growth, can be readily seen and counted, and its approximate age determined by actual enumeration, and thus satisfactorily settle that interesting fact beyond the least peradventure.

|

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. |

| DRIVING THROUGH LIVING TREE, “WAWONA." |

Just below this is a very large prostrate tree, in possession of the questionable name of “Claveau’s Saloon,” through which, in former years, two horsemen could ride abreast for eighty feet; but, another “big tree” falling across it, has broken in its roof; yet, above this, people can ride through, for thirty feet. The few noticeable examples here presented can be but barely sufficient to illustrate the peculiarities and immense proportions of this extraordinary genus; and when our delighted vision can be feasted upon such magnificent representatives as the “Queen of the Forest,” “Monadnock,” “Keystone,” “Virginia and Maryland,” “Board of Commissioners,” the “Diamond Group,” and many other equally perfect trees, varying in circumference from sixty to ninety feet, and in altitude from two hundred and fifty to two hundred and seventy-five feet, we become satisfied that, like the Queen of Sheba’s opinion of the wisdom of Solomon, “The half hath not been told,” and never can be; and these become suggestive of the rich banquet in store for those who can here worship nature for her own glorious sake.

And, be it remembered, that the “big trees,” large as they are in themselves, are but a small proportion of this magnificent forest growth, intermixed and interwoven, as they are, with the drooping boughs of the white blossoming dogwood, Cornus Nutallii; or the rich purple flowers of the ceanothus, Ceanothus thyrsiflorus; or the feathery bunches of white California lilac, Ceanothus integerrimus, and other species of this beautiful plant; and to which must be added, the ever fragrant masses of blossom which adorn the azaleas, Azalea occidentalis, or the spice bush, Calycanthus occidentalis, with its long, bright green leaves, and singular, wine-colored flowers; and from among all of these will be seen peeping the large white bells of the “Lady Washington Lily,” Lilium Washingtonianum; or the Little Red Lily, Lilium parvum, with the gorgeously bright red and orange-colored Tiger Lilies, Lilium pardalinum, and L. Humboldtii; and other flowers ad infinitum.

But, reluctantly as the word “good-bye” may sometimes fall upon the ear, or strike home to the heart, it must occasionally be spoken; yet, before doing this, let us take just one outlook from

Here is a jutting ridge that stands boldly out from the grove, but a short distance from the road; and, as this affords us a comprehensive bird’s-eye view of the surrounding country, with its distant mountain ranges, and long lines of trees; and more especially of the grassy meadows and numerous buildings which constitute the Big Tree Station, “Wawona,” two thousand five hundred feet below us, we shall feel that we are well repaid for our trouble.

It may be well here to state that the Mariposa Big Tree Grove, with the Yo Semite Valley, was donated to the State of California in 1864, as recorded in Chapter VIII of this volume.

As this is only about ten miles distant from the Mariposa Grove; and will, without doubt, at an early day, form one of the many delightful excursions from Wawona, a brief outline concerning it may not be unacceptable. On a warm summer evening in July, 1856, Mr. Galen Clark was riding along the ridge which divides the waters of Big Creek from the Fresno, and caught sight of a large group of trees similar to those found in the Mariposa Grove. Two days afterward, Mr. L. A. Holmes, of the Mariposa Gazette, and Judge Fitzhugh, while on a hunting excursion, saw the tracks of Mr. Clark’s mule as they passed the same group; and as both these parties were very thirsty at the time, and near the top of the ridge at sundown, without water for themselves and animals, they were anxious to find this luxury, and a good camping-place, before dark. Consequently, they did not deem it best to tarry to explore, intending to pay it a visit at some early time of leisure in the future. This interesting task however, seemed to be reserved for Mr. Clark—to whom the world is indebted for this new discovery—and the writer, on the second and third days of July, 1859.

With our fire-arms across our shoulders, and our blankets and a couple of days’ provisions at the back of our saddles, we proceeded for a short distance through the thick, heavy grass of the meadow, and commenced the gradual ascent of a well-timbered side-hill, on the edge of the valley, and up and over numerous ridges, all of which were more or less covered with wild flowers. About six o’clock the same evening, we reached the first tree of that which has since been known as the “Fresno Grove” in safety; but as the sun was fast sinking, we deemed it prudent to look out for a good camping-ground before darkness precluded the opportunity, and postpone exploration for the present. Fortunately we soon found one, and at the only patch of grass to be seen in several miles, as afterwards discovered.

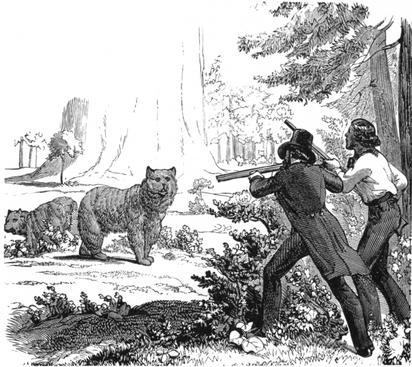

As we were making our way through the forest towards it, thinking and feeling that probably we were the first whites who had ever broken the profound solitudes of that grove, we heard a splashing sound, coming from the direction in which we were heading. This, with the moving and rustling of bushes, and the snapping of dead sticks, reminded us that we were possibly invading the secluded home of the grizzly bear, and might, almost before we knew it, have good sport or great danger, to add variety to our experiences. Hastily dismounting and unsaddling, we at once picketed our animals on the grass-plat; still wet with the spurtings of bear’s feet, that had hurriedly made tracks across it; then, kindling a fire, to indicate by its smoke the direction of our camp, we started quietly out

Cautiously peering over a low ridge, not over a hundred yards from our horses, we saw two large bears moving slowly

|

| BEAR HUNT IN THE FRESNO GROVE. |

We immediately started in pursuit; and although their course could be easily followed by the tracks made, as well as the blood from the wounded bear, they reached the shelter of a dense mass of chaparral, before we could overtake them, even by a shot; as they traveled much faster than we could, and were there securely hidden from sight. Deeming it impolitic and unwise to follow them, by creeping under and among the bushes forming their place of refuge, if not their lair, we walked around upon the lookout, until the deepening darkness, as if in sympathy with bruin, completed their hiding, and admonished our return to camp without the expected prize; and where, when supper was ended, we soon found forgetfulness in sleep. After a very early breakfast we again renewed our search for the hoped-for game; but, although we ventured into the chaparral, and I looked under this and that heavier clump of bushes, in the hopes of finding it; we never saw either of them afterwards. Finding nothing larger than grouse, we bagged a few of those, and then commenced our explorations.

We spent the whole day wandering through the dense forest which forms this splendid grove; looking at this one, admiring that, and measuring others, without attempting to ascertain the exact number of Sequoias found here; yet concluded that there were about five hundred of well developed Big Trees, on about as many acres of gently undulating land. The two largest we could find measured eighty-one feet each in circumference, were well formed, and straightly tapering from the ground to their tops. Many others that were equally sound, and as symmetrically proportioned, were from fifty-one feet to seventy-five feet in girth. The sugar pines were enormously large for that species; as one that was near our camp measured twenty-nine feet six inches in circumference, and two hundred and thirty-seven feet in length. None of the trees in this grove were badly deformed by fire.

But now, if you please, let us imagine that we have taken the delightful, forest-arched ride, from the Mariposa Big Tree Grove, down to Wawona; as, before we leave its enjoyable precincts, there are many points of interest still to visit, and among them

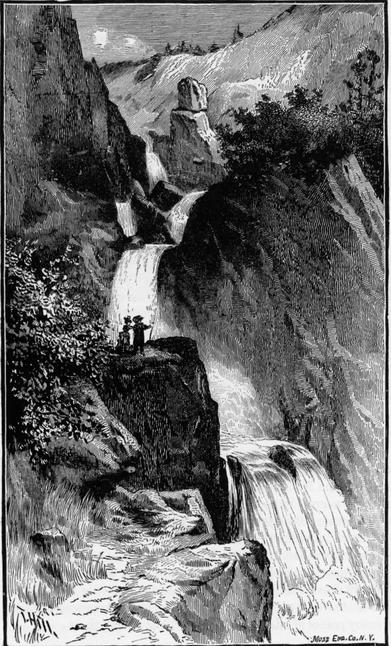

|

| Drawn by T. Hill. |

| THE CHIL-NOO-AL-NA FALLS. |

| NEAR WAWONA. |

|

Hail me, dashing Chil-noo-al-na!

Here I love to shout and clamber,

Here I dwell with nymphs and dryads;

Dashing into space so grandly,

In the Sylvan Grotto hiding,

Lo! the Frost King brings his shackles,

Though he tries with deathly stillness,

For I’m Monarch of these forests,

I am mighty in my power.

—Mrs. Fannie Bruce Cook. |

The beautiful pen drawing on the adjoining page, kindly made by Mr. Thos. Hill for this work, will tell how richly a visit there will be repaid, by either walking or riding the two miles of distance from the hotel.

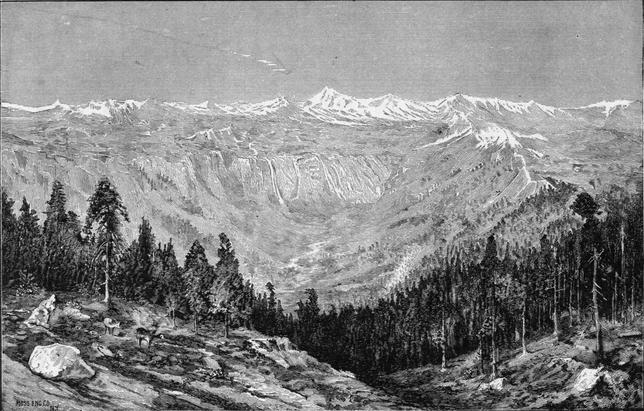

Another compensating and satisfying sally from Wawona is to

The name given to the highest point of the Chow-chilla Mountains, lying westerly from the hotel. This suggestive nomenclature was given to it owing to the Indians having made choice of that point as a signal station, from which to telegraph, by fire and smoke, to all their Indian allies, both far and near, any message they might wish to send. Its commanding outlook will at once commend their choice for the selection. The accompanying engraving, also from a sketch by Mr. Hill, significantly indicates the wonderful panorama rolled out before us from that glorious scenic standpoint, when looking east. On any clear day every deep gorge, and element-chiseled furrow, every lofty peak, and storm-defying crag, of the great chain of the Sierras, for a radius of nearly one hundred miles, is distinctly visible to the naked eye. It is one vast sea of mountains, whose storm-crested waves tell of their billowy upheaval by elemental forces, and suggest that they were afterwards suddenly cooled, and solidified into rock, when in most violent ebullition; and that while the impressive individuality of each culminating crest is measurably dwarfed by distance, the general effect of the whole is inexplicably enhanced by the wonderful combination.

Looking west how suddenly the scene changes from storm to calm; for, while the near mountain ridges, which form the foreground to the picture, remind us of the former, the receding foot-hills, and broad valleys peacefully stretching to the horizon, tell only of the latter; so that the one by contrast, exalts the impressiveness of the other, and provides, as a whole, a satisfying “feast of good things, of wines on the lees, well refined,” that will be pleasantly remembered as long as memory reigns queen upon her throne.

|

| Drawn by T. Hill. |

| THE SIERRAS FROM SIGNAL PEAK. |

Such as the excellent trout fishing in the south fork of the Merced, that runs directly past the hotel; the walk to the Fish Pond, and boat ride upon it; visit to Hill’s Point, for the distant view of Chil-noo-al-na Falls; the Soda Spring, and grove of young Sequoias near; and other places of interest, which not only enable visitors to spend their time pleasantly here, but become sufficiently attractive to induce many to tarry months at Wawona, and some for the whole summer. The cheery liveliness of its constantly changing throng of visitors; its salubrious and exhilarating climate; the balmy fragrance of its surrounding pine forests, and charming variety of scenery, would seem to unite in making this a most delightful resort for invalids.

But as the glorious scenes of the Yo Semite are in immediate prospect, and as anticipation has long been on tiptoe to enter their sublime precincts, let us cross the South Fork Bridge at Wawona, and start at once upon our deeply interesting journey.

Following the eastern bank of that stream for about a mile, we commence the gradual ascent of a long hill, the outlook from which is everywhere full of inspiriting pleasure. On both sides of the road the gossamer, floss-like blossoms of the Mountain Mahogany, Cercocarpus ledifolius; the Manzanita, Arctostaphylos glauca (What a name for such a beautiful shrub!) with its pinkish-white, wax-like, and globe-shaped blossoms, hanging in bunches, challenge our admiration. But, on we roll, the landscape broadening and the gulches, like our interest, deepening as we ascend, until we come to “Lookout Point.” Here grandeur culminates, and an admonition spontaneously finds its way to the lips, “Oh! driver, please to stop here just one minute for this marvelous view.” This is five thousand five hundred and sixty feet above sea level.

Before long the darkening forest shadows we are entering remind us that we shall soon be at Eleven Mile Station, and at “West Woods.” West Woods is the name given to Mr. John W. Woods, an open-faced and kindly-hearted hunter, who makes this his lonely abiding-place both winter and summer. A short distance beyond this we attain the highest point on the road, six thousand one hundred and sixty feet above the sea. About half a mile further on we arrive at Chinquapin Flat, where the diverging road for Glacier Point, fourteen miles distant, leaves the main one. From here every step towards Yo Semite is constantly alternating and changing in scenic grandeur; now we emerge from forest shades to open glades; then look into the deep cañon of the Merced River, then upon the leaping tributaries of Cascade Creek; until, at last, we come to that unspeakably glorious view which suddenly breaks upon us at

Here language fails; for neither the pencil’s creative power, the painter’s eliminating art, photography, pen, or human tongue, can adequately portray the scene of unutterable sublimity that is now out-rolled before us. Longfellow’s beautiful thought seems uppermost: “Earth has built the great watch-towers of the mountains, and they lift their heads far into the sky, and gaze ever upward and around to see if the Judge of the World comes not"—even while we are entrancedly waiting.

Deep down in the mountain-walled gorge before us sleeps the great Valley. Its beautiful glades, its peacefully glinting river, its dark green pines, its heavily timbered slopes; all hemmed-in, bounded, by cliff-encompassing domes, and spires; with crags and peaks, from three to five thousand feet in height, and over which there gracefully leap the most charming of water-falls, from nine hundred to three thousand feet in height above the meadows. While “the laurel-crowned king of the vale,” grand old El Capitan, with a vertical mountain cleavage of three thousand three hundred feet, stands out most nobly defiant, and asserts the impressive individuality of his wonderful presence; while over all of these an atmospheric veil of ethereal purple haze is enchantingly thrown, with the whole bathed in sunshine, to heighten the general loveliness of the scene. No change of time or circumstance can ever efface from memory this glorious first glimpse of Yo Semite.

Next: Chapter 19 • Index • Previous: Chapter 17

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/18.html