| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Mariposa Route >

Next: Chapter 22 • Index • Previous: Chapter 20

|

We live in deeds, not years; in thoughts, not breaths;

In feelings, not in figures on a dial. We should count time by heart throbs. He most lives Who thinks most, feels the noblest, acts the best.

—Bailey’s

Festus.

|

|

A land of promise flowing with the milk

And honey of delicious memories.

—Tennyson’s

The Lover’s Tale.

|

|

Tis pleasant through the loop-holes of retreat

To peep at such a world.

—Cowper’s

Task, Bk. IV

|

As recorded in earlier chapters, this was the first and original route ever traveled to the Yo Semite Valley; and its fearless people the first to enter it, in pursuit of the marauding and murderous Indians in 1851; and afterwards to make the existence of such a marvelous spot known abroad. The great public, therefore, throughout the civilized world, owe an agreeable, enduring, and never-to-be-canceled debt of gratitude to the people of Mariposa, for the glorious heritage they were thus instrumental in conferring upon them. Unlike any other ordinary indebtedness, however, its remembrance will impart none but pleasurable emotions. In winding our way among its rich and beautiful hills, then, the memory of the early struggles of its people with the foe, and the boon of the remarkable discovery which followed, will bespeak for our journey over this historic ground far more than mere ordinary interest.

The accompanying table of distances and altitudes, with the map of routes, will indicate that the place of departure for Yo Semite on the Mariposa route, is, like the one via Coulterville, from Merced, on the Southern Pacific Railroad.

|

THE MARIPOSA ROUTE,

From San Francisco, via Lathrop, Merced, Mariposa, Mariposa Big Tree Station

|

|||||

| STATIONS. | Distances in Miles. | ||||

| Between consecutive points. |

From San Francisco. |

From Yo Semite Valley. |

Altitude, in feet above Sea Level. |

||

|

By Railway. |

.... | .... | 152.03 | ||

| From San Francisco to— | |||||

|

Lathrop, junction of the Southern Pacific with the Central

Pacific Railroad (b c) |

94.03 | 94.03 | 58.00 | 28 | |

| Merced, on Southern Pacific Railroad (a b c d) | 58.00 | 152.03 | ... | 171 | |

|

By Carriage Road. | .... | .... | 93.95 | ||

| From Merced to— | |||||

| Half-way House, watering station (b c) | 6.35 | 6.35 | 87.60 | 215 | |

| Forks of Road to Snelling’s | 0.87 | 7.22 | 86.73 | 225 | |

| Lava Bed Station (c d) | 7.26 | 14.48 | 79.47 | 446 | |

| Griffith’s Ranch | 3.63 | 18.11 | 75.84 | 473 | |

| Hornitos (b c) | 4.35 | 22.46 | 71.49 | 847 | |

| Forks of Road to Indian Gulch | 1.52 | 23.98 | 69.97 | 898 | |

| Smith’s Ranch | 2.44 | 26.42 | 67.53 | 1,047 | |

| Corbett’s Ranch (b c) | 1.91 | 28.83 | 65.62 | 1,075 | |

| Toll House | 1.81 | 30.14 | 63.81 | 1,598 | |

| Toll House | 2.83 | 32.97 | 60.98 | 1,780 | |

| Princeton (b c) | 2.65 | 35.62 | 58.33 | 2,104 | |

| Lewis’ Ranch (b c) | 3.54 | 39.16 | 54.79 | 2,112 | |

| Mariposa (a b c d) | 1.70 | 40.86 | 53.09 | 1,932 | |

| Mormon Bar (b c) | 1.89 | 42.75 | 51.20 | 1,630 | |

| Sebastopol Flat (b c) | 2.76 | 45.51 | 48.44 | 2,210 | |

| Thompson’s Ranch (b c) | 3.51 | 49.02 | 44.93 | 2,114 | |

| Turner’s, formerly De Long’s (b c) | 3.93 | 52.95 | 41.00 | 2,741 | |

| Cold Spring (b c d) | 4.36 | 57.31 | 36.64 | 3,126 | |

| Summit of Chowchilla Mountain | 5.24 | 62.55 | 31.40 | 5,605 | |

| Wawona* (a b c d) | 4.50 | 67.05 | 26.90 | 3,923 | |

| Eleven Mile Station (b c d) | 10.76 | 77.81 | 16.14 | 5,567 | |

| El Capitan (lower iron) Bridge, Yo Semite Valley | 12.51 | 90.32 | 3.63 | 3,843 | |

| Leidig’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 2.56 | 92.88 | 1.07 | .... | |

| Cook’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 0.30 | 93.18 | 0.77 | .... | |

| Barnard’s Hotel. Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 0.77 | 93.95 | ... | 3,934 | |

|

* From Wawona (Clark’s) to and through the Mariposa Big Tree Groves, and back to Big

Tree Station, 17 miles. |

|||||

|

RECAPITULATION. |

|||||

| By railway | 152.03 miles. | ||||

| By carriage road | 93.95 ” | ||||

| Big Tree Groves and back to station | 17.00 ” | ||||

| ————— | |||||

| Total distance | 262.98 miles. | ||||

|

| INDIAN WOMAN PANNING OUT GOLD. |

|

| "THE PROSPECTOR." |

Once among the more abruptly formed uplands of the county, evidences of gold mining are on every hand; and the irrepressible prospector for gold is met hunting for hidden treasures. The world owes much to the undiscouraged energy of this class of men; as, but for their labors, much of the wealth of the world would have been undiscovered. Good luck then to the prospector; as blessings from the gold he may discover will, let us hope, bring prosperity and happiness to himself and family, and be more or less shared in by all.

As much of the way, on any route we may elect to take for Yo Semite, passes directly through some portions of the mining region, where the principal occupation of its people consists in extracting the precious metal; and inasmuch as the stranger, who has perhaps never looked upon gold-mining scenes, feels a thrill of fascination in the thought of seeing people “digging out gold” from the earth, it creates the temptation to give a brief outline of the method by which this is accomplished. And by way of commencement let me explain that there are two distinctly different sets of conditions, or of circumstances, under which gold is found, and which necessarily require two different systems of treatment; one being in surface soils or gravels, and the other in a ledge or vein formation; the former is called “Placer Mining,” and the latter “Quartz Mining.”

After the discovery of gold upon a bar of the American River, Coloma, California, January 19, 1848, and for several years thereafter, it was supposed that the precious metal was only to be found in rivers, gulches, and ravines; then, experience revealed the fact that gold was also to be found in flats, and gravelly hills, away from existing water-courses; then, advancing knowledge presented scientific certainty that even the gold found everywhere in placer diggings, had come, mainly, from quartz veins, or ledges—quartz being the principal matrix for its production. Let us, therefore, follow the earliest and most primitive methods, and see how gold was then taken out of surface mines.

The prospector having arrived at a spot that looked inviting, at once cleared away the rocks and rubbish that might cover up the “pay dirt;” then he would fill his pan, and carry it to the nearest pool or stream of water, set it down into it, and, when immersed beneath the surface, would commence an oscillatory and slightly tipping and rotary motion forward, by which the finer particles of soil were induced to float away, and the pieces of rock or pebbles near the top to become washed; these were picked out and thrown away; this process was repeated until there was nothing left in the pan but the gold, and which, being the heaviest of all, would keep settling down into the lowest inside edge, and was thence taken out.

|

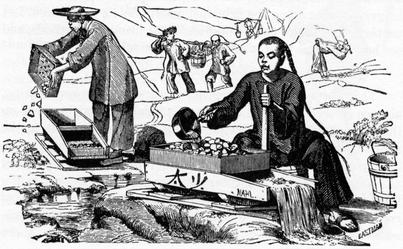

| THE BATEA, OR MEXICAN BOWL. |

This, as will be seen by the illustration (for it is still in use among the Chinese), was a wonderful improvement upon panning; as two men, one to procure and carry the pay dirt, and the other to wash it, could readily average a hundred bucketfuls per day each.

|

| CHINAMEN WASHING OUT GOLD WITH A CRADLE. |

The plan of using the cradle will be very clear; as the pay dirt, whether of soil or gravel, was emptied into the “hopper” at the top of the machine, the bottom of which was perforated with holes half an inch in diameter; and while water was being poured in upon the dirt with one hand the cradle was rocked with the other. This complex movement was about as difficult of attainment to the novice, as that of the school-boy’s attempt to rub his nose with one hand while patting his chest with the other. By this process, however, all the gold would pass through the bottom of the hopper, to be caught upon an apron immediately beneath it, and there saved; or, escaping the apron, would lodge in one or other of the divisions across the bottom. Any pieces of gold too large to pass through the hopper (and there have been many of these) were joyfully picked out, exulted over, and then dropped into the “lucky buckskin purse” and there taken care of.

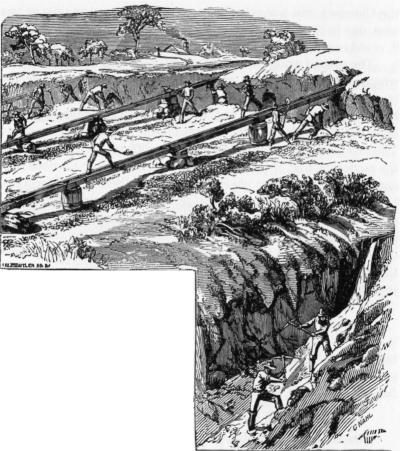

Great as was the advance made from the pan to the cradle, that in turn had to give way to the “Long Tom,” by which thousands of bucketfuls (the only method of counting or of estimating quantities in those days) would be washed in a single day. But this again had to fall into desuetude, and be superseded by

The accompanying illustration will give a general outline of this method, almost at a glance. Long troughs, called “sluices,” about twelve feet in length, are made to fit into each other at the end; the number used depending upon the clayey toughness of the dirt to be washed, or the fineness of the gold to be saved; and varying from half a dozen to over one hundred lengths. Across the bottom of these sluice-boxes bars are placed, partly to intercept the too rapid passage of the material shoveled into them, but, principally, to form a riffle and an eddy, wherein to provide a place of settlement for the gold being washed out. These troughs

| |

| SLUICE MINING. | GROUND SLUICING |

“Ground sluicing” consists of turning a stream of water into a mining claim, by which all the light and worthless material, assisted by miner’s picks, is made to float away; when the gold settles down among the rocks or gravel; and with the better quality of earth remaining, is there saved, and afterwards shoveled into the sluice for gathering in and cleaning up.

This is generally carried on by what is known as the “Hydraulic Method.” For the better apprehending of this, perhaps it will be desirable to explain that in nearly all the mining districts there are immense deposits of water-washed gravel, forming whole ridges and hills many hundreds of feet high. These have been placed there by agencies not existing in the present day; but how they came, or when, is left entirely to the geologist or mining expert. I do not know this, nor do I know any one that does.

|

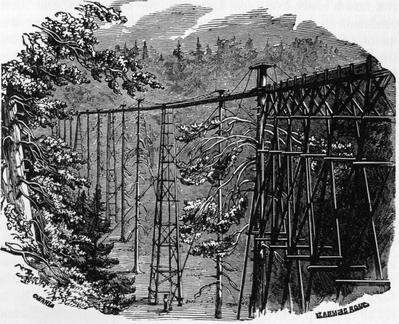

| WATER FLUME ACROSS A HOLLOW BETWEEN RIDGES. |

That they are there, and that they contain auriferous gravel in untold abundance, is beyond any doubt; and it is with these, and the methods of extracting the precious metal therefrom, that we now have to do. Additional interest may accrue from the fact that, owing to the wonderful efficiency of hydraulic mining, and the accredited filling up of navigable streams from the “slickens” or gravel floated therefrom, their working has been legally estopped by the courts.

Water, being the great working force in all placer mines, was especially needed to tear down these mountains of gravel, and wash out the gold; consequently, all sorts of canals, flumes, and ditches were constructed, for conveying that invaluable element from living streams to the mining districts, at an enormous expense. Once upon the ridge it was distributed from the main canal by hose, or in smaller ditches, to the different mines, where it was run into a sheet-iron pipe, largest at the upper end, and there confined; so that the entire weight of the inclosed water, frequently having hundreds of feet of vertical pressure, escaping through a nozzle at the lower end, like a fireman’s pipe, tore down the gravel with tremendous force, and caused immense masses, frequently many scores of tons in weight, to “cave down,” and not only to break themselves to pieces by the fall, but frequently to bury the too venturesome miner underneath them. Sometimes tunnels are driven far into these gravelly deposits, and hundreds of kegs of blasting powder are simultaneously exploded, to shake the banks into pieces, so that the gravel may be more effectually washed by the water. Frequently over a thousand miner’s inches of this element are brought to play, steadily, upon these “Hydraulic Mines.” After several weeks have been consumed at this, a “clean up” is made, the results “bagged,” and sent by express to the San Francisco Mint. It can readily be seen what vast quantities of this material would be annually run into the beds of tributary streams, the tendency of which would be to choke them up, and force an overflowing flood both of water and sediment upon the low adjacent lands.

This consists in extracting the precious metal from quartz, which is the principal matrix for gold (although not the only one), the ledges or veins of which sometimes extend several thousand feet down into the earth. Indeed it is more than probable that from this source nearly all the gold found in placer mining has originally come; as the action of air, water, sunshine, frost, and other elements have disintegrated the matrix containing the gold, and set the precious metal free. Heavy rains and great floods have washed the lighter silica into the water-courses, and thence to the valleys, thus forming the soil and gravel that has buried up the gold; and it was here that the early gold miner found his rewarding treasures.

Quartz ledges, or veins, are readily discoverable by their white crests or belts cropping above or mapping the hills; it must not, however, be supposed that each and every one of these possesses an inexhaustible mine of untold wealth; far from it. Like true worth in humanity, it is not self-assertive prominence that is the unerring augury of excellence, as the boldest fronted are proverbially of the least intrinsic value. The richest of gold producing veins are those which are generally without distinguishing features outwardly, and are composed of what miners call “rotten quartz.” From this material (but not from this only by any means) much of the wealth in and from California, and elsewhere, has been and is being produced.

|

| MINER’S PAN AND HORN SPOON. |

|

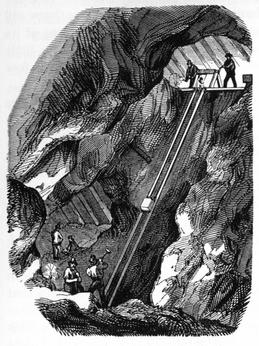

| MINERS SINKING A SHAFT. |

The principle of separating the precious metals from the matrix in which they are found, is, substantially, the same in all cases; their treatment only differing according to the presence and extent of the baser metals; and it is simply this: The matrix, whether it be quartz or any other, is reduced to as fine a powder

|

| FOLLOWING DOWN THE LEDGE. |

Hornitos (Spanish for little oven), is the first mining town entered in Mariposa County; which, being originally settled by Mexicans, and still having numerous representatives of that nationality, has more the appearance of a Spanish than an American town. Its quartz ledges, however, are now attracting other classes of residents thither, who are gradually changing its characteristics. Whatever changes may come to its people there will never be any serious questioning as to the appositeness of its name—unless it could be made to express something a little hotter! This place is only about eight hundred and fifty feet above sea level.

A few miles easterly of Hornitos we enter upon the once famous “Fremont’s Mariposa Grant;” and, as one passes through the various settlements that have been made upon it, how memory reverts to the busy hum of mining and of mining life that once pulsated through the great arteries of this mineral aorta, giving to it a strength of purpose that brought a prosperity which became proverbial. It has long been a subject of legitimate discussion, however, whether or not the best interests of this entire region would or would not have been best subserved, had the Fremont grant never been floated upon this mining district; notwithstanding the large sums of money that have been expended here at different times, by the various companies that have represented that ownership (for it has always been in some kind of financial or managerial trouble). From the Benton Mills on the Merced to Mormon Bar on Mariposa Creek, such towns as Bear Valley, Agua Fria, Princeton, and Mariposa, prove that the elements of success have been, and there can be no doubt are still here, and only await favorable development to bring back the halcyon days of yore, although much of the cream has been taken from the placer mines.

As we ride along we can see that every gulch, ravine, or flat upon the way, bears the unmistakable scars of an active mining life, and gives unmistakable evidence that a miner’s labors, if they bring prosperity to himself and family, and make acceptable addition to the country’s wealth, invariably bring desolation to the landscape; yet, even this, is relieved by cultivated gardens, orchards and vineyards, near and among the settlements; while Mount Bullion, “the backbone of the county,” and its timbered spurs, attract attention by their scenic boldness. From the northern crest of this ridge some of the vertical cliffs of the Yo Semite are distinctly visible, although some forty miles distant.

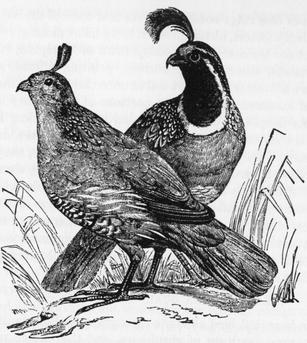

But here we are in the county town of Mariposa; its court house, hotels, stores, livery stables, printing offices, schools, churches and numerous shops, tell at once that it is still the active center of business for the main portions of the county—And although its people have had to contend with marauding Indians, submit to the desolating losses of fire at sundry times, and bear their share of the customary ups and downs of life, they never seem to have been discouraged. That the reward may come in the increase of business a thousand-fold is the writer’s heartiest and most devout wish. After saying a pleasant good-bye (and I never knew any other), as soon as we reach the lower end of town we pass a quartz mill of some forty stamps, now unused; and at the outskirts of the town, we can see covies of quail running hither and thither in every direction.

THE CALIFORNIA QUAIL (Perdix Californica).

This beautiful bird abounds throughout California; if we except districts destitute of shrubbery, and the higher mountain region. It is a little larger than the quail of the Northern and Western States, but as a tid-bit for the epicure is not fully its equal; its habits making the flesh harder and tougher. From their great plentifulness, in many sections, there is no difficulty in procuring them in large numbers for market. They can be partially tamed, when kept in capacious cages, or in inclosures where they can get to the ground; they will they then lay their eggs, and rear their young, like the common fowl. Their fecundity is remarkable; a single female, domesticated by a friend of mine, in a single summer, laid the astonishing number of seventy-nine eggs. She was, moreover, very tame, and would eat from the hand of her mistress, although invariably shy to strangers. Sometimes the male bird was very pugnacious for several days together, when her ladyship had to take refuge in a corner, or seek the protection of a tea-saucer, from which they were daily fed.

The valley quail must not be confounded with that of the

|

| PAIR OF CALIFORNIA VALLEY QUAIL. |

Our road now runs down Mariposa Creek, past quartz ledges, and placer mines, to Mormon Bar; where it commences to ascend the hills at an easy grade, for several miles, among buckeye bushes, Aesculus Californica; greasewood, Ceanothus cuneatits; leatherwood, Fremontia Californica; and white post oaks, Quercus Douglasii.

| |

| Photo by Carleton E. Watkins. | Photo-typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| Hydraulic Mining. | |

| (See pages 299-300.) | |

Just about dark one evening as three of us were jogging along this road (we had a camping outfit with us), and anxious to obtain necessary feed for our animals for the night, we stopped at the gate of a wayside house, at which stood a boy who had

|

| THE BOY THAT “DIDN’T KNOW NUFFINK." |

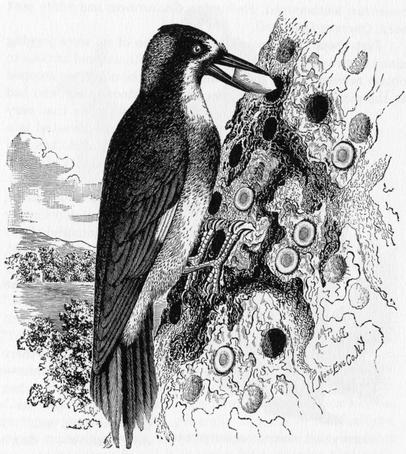

When riding upon nearly every highway in California, there can be seen a brilliant-coated woodpecker, flitting hither and thither; the red, white, and black of his plume glinting brightly in the sunshine. It is the red-headed woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus). The Spanish people here call it El Carpintero, or Carpenter Woodpecker, from his singular habit of boring into the bark

|

| THE RED-HEADED WOODPECKER (Melanerpes formicivorus.) |

The red-headed woodpecker, contrary to the habits of birds, provides for future emergencies; and from instincts of its own, anticipates some coming want, and prepares for it accordingly. It is an open question, however, whether or not the acorn forms part of its food; or is only the treasury of an insect possessing essential qualities for the woodpecker’s existence, when such are unattainable elsewhere; some contending for the former, while others as persistently insist upon the latter. The same habit is possessed, though not to the same extent, by the Melanerpes erythocephalus, east of the Rocky Mountains.

Our ride for many miles now is among or over gently rolling gravelly hills, covered with a light growth of shrubbery and white post oaks; where nearly all the available flats, or small valleys on streams, have been converted into grain fields, or gardens and orchards, so that numerous little tenements add variety to the journey. Farther on, the stately pines once tempted the erection of saw-mills, one of which, White and Hatch’s, became famous for its excellence as a lunch house for Yo Semite tourists. These industries made the road lively by the coming and going of teams, either with supplies up for mining settlements and ranches, or with lumber down for the cities and towns.

Finally we reach Conway’s at Cold Spring (where an excellent meal and good bed can always be obtained), and here commence the ascent of Chow-chilla Mountain. In five and a quarter miles, from Conway’s to the summit, we make a rise of two thousand four hundred and seventy-nine feet. But the many beautiful live oaks, Quercus chrysolepis; black oaks, Q. Kelloggii; yellow pines, Pinus ponderosa; sugar pine, P. Lambertiana; and red cedar, Libocedrus decurrens, that throw their welcome shadows on the road, or allow of openings between them to afford glimpses of the charming scenery beyond, beguile every mile and moment of the way. And when once upon the summit what a tree feast is here provided, which continues all the way to Wawona.

Reveling in memories of such a luxuriant growth one cannot wonder that the great newspaper genius, Horace Greeley, should thus write about it:—

Here let me renew my tribute to the marvelous bounty and beauty of the forests of this whole mountain region. The Sierra Nevadas lack the glorious glaciers, the frequent rains, the rich verdure, the abundant cataracts of the Alps; but they far surpass them—they surpass any other mountains I ever saw—in the wealth and grace of their trees. Look down from almost any of their peaks, and your range of vision is filled, bounded, satisfied, by what might be termed a tempest-tossed sea of evergreens, filling every upland valley, covering every hill-side, crowning every peak, but the highest, with their unfading luxuriance. That I saw, during this day’s travel, many hundreds of pines eight feet in diameter, with cedars at least six feet, I am confident; and there were miles of such, and smaller trees of like genus, standing as thick as they could grow. Steep mountain-sides, allowing these giants to grow, rank above rank, without obstructing each other’s sunshine, seem peculiarly favorable to the production of these serviceable giants. But the Summit Meadows are peculiar in their heavy fringe of balsam fir, of all sizes, from those barely one foot high to those hardly less than two hundred, their branches surrounding them in collars, their extremities gracefully bent down by the weight of winter snows, making them here, I am confident, the most beautiful trees on earth. The dry promontories which separate these meadows are also covered with a species of spruce, which is only less graceful than the firs aforesaid. I never before enjoyed such a tree-feast as on this wearing, difficult ride.*

* Mr. Greeley being in a hurry (this had become habitual with him), and anxious to see as much as possible in the limited time he had allowed himself, rode from Bear Valley to Yo Semite, over sixty miles, in a single day, or thereabouts; thirty-eight of which were on the back of one of the hardest trotting mules in America; and as he had not been in the saddle for thirty years, was somewhat inclined to portliness, and the possessor of a cuticle as tender as that of a child, there was but little of the unabrased article left, when he arrived in the valley at one o’clock the next morning. His suffering, must, therefore, have been intense; and, being utterly helpless, he was carefully lifted from the saddle, his comfort cared for as much as possible under the circumstances, and, at his own request, put supperless to bed. Just before noon of the day of his arrival, he was assisted from his couch, and, as he had speaking engagements to fulfill, after a light breakfast, taken as distinguished guests are honored with a toast, he was again lifted into the saddle, and without seeing any of the great sights beyond the hotel, made a returning ride of twenty-four miles, to Clark’s. He was seen by the writer, in San Francisco, some three weeks afterwards shuffling along the sidewalk, slowly; and when allusion was made to his too evident lameness the response came: “Oh! Mr. H., you cannot realize how much I have suffered from that jaunt to the Yo Semite.” To speak glowingly, therefore, of anything, after such an experience, proves Mr. Greeley to have been more than an ordinary man.

Next: Chapter 22 • Index • Previous: Chapter 20

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/21.html