| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Big Oak Flat Route >

Next: Chapter 23 • Index • Previous: Chapter 21

|

Know the true value of time; snatch, seize, and enjoy every moment of it.

Never put off till to-morrow what you can do to-day.

—Earl of Chestierfield’s

Letters to his Son.

|

|

Wherefore did Nature pour her bounties forth

With a full and unwithdrawing hand, Covering the earth with odors, fruits, and Rocks, But all to please and sate the curious taste?

—

Milton’s

Comus.

|

|

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale

Her infinite variety.

—Shakespear’s

Anthony and Cleopatra.

|

A glance at the outline map of routes will show that our course is via Stockton and Milton; just the same, so far, as that via the Calaveras Big Tree Groves; but, just beyond the Reservoir House and reservoir, our road trends to the right, through Copperopolis—so named from the immense deposits of copper ore once found here, the extraction of which employed many hundreds of men. Now its deserted streets and decaying buildings tell the sad story that the copper mines are no longer worked; and suggest the business stagnation that ensued. But the coachman’s cheery “All aboard” will cut short any sympathetic reveries at the change, and keep us rolling on among white post oaks and bull pines, until we reach Byrne’s Ferry at the Stanislaus River. It is simply presumed that the name “Byrne’s Ferry” will ever be continued, although a substantial bridge made this a polite fiction of the past a score or more years ago.

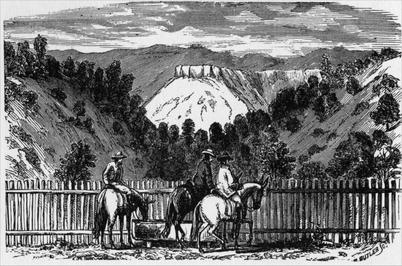

Here, however, we see disconnected parts of a mountain of volcanic origin, which to appearance is “as level as a table,” and which is called by everybody living near it, Table Mountain.

|

THE BIG OAK FLAT ROUTE,

From San Francisco, via Stockton, Milton, Chinese Camp, and Big Oak Flat, to

|

|||||

| STATIONS. | Distances in Miles. | ||||

| Between consecutive points. |

From San Francisco. |

From Yo Semite Valley. |

Altitude, in feet above Sea Level. |

||

|

By Railway. |

.... | .... | 133.05 | ||

| From San Francisco to— | |||||

|

Lathrop, junction of the Central Pacific with the Southern

Pacific Railroad (b) |

94.03 | 94.03 | 39.02 | 28 | |

| Stockton, on Central Pacific Railroad (a b c d) | 9.02 | 103.05 | 30.00 | 29 | |

| Milton, on Stockton and Copperopolis Railroad (b c d) | 30.00 | 133.05 | ... | 376 | |

|

By Carriage Road. | .... | .... | 91.28 | ||

| From Milton to— | |||||

| Reservoir House (b c) | 6.13 | 6.13 | 85.15 | 1,013 | |

| Copperopolis (b c d) | 8.70 | 14.83 | 76.45 | 1,015 | |

| Byrne’s Ferry Bridge, Stanislaus River | 7.00 | 21.83 | 69.45 | 475 | |

| Goodwin’s, Table Mountain Pass (b c d) | 3.50 | 25.33 | 65.95 | 1,050 | |

| Chinese Camp (a b c d) | 3.50 | 28.83 | 62.45 | 1,299 | |

| Moffitt’s Bridge | 4.18 | 33.01 | 58.27 | 602 | |

| Keith’s Orchard and Vineyard | 1.03 | 34.04 | 57.24 | 612 | |

| Stevens’ Bar Ferry | 1.24 | 35.28 | 56.00 | 614 | |

| Culbertson’s Vineyard (c) | 3.45 | 38.73 | 52.55 | 980 | |

| Priest’s Hotel (a b c d) | 2.21 | 40.94 | 50.34 | 2,558 | |

| Big Oak Flat (b c) | 1.07 | 42.01 | 49.27 | 2,823 | |

| Groveland (b c) | 2.24 | 44.25 | 47.03 | 2,828 | |

| Second Garrote | 2.15 | 46.40 | 44.88 | 2,857 | |

| Sprague’s Ranch (b c) | 4.97 | 51.37 | 39.91 | 2,950 | |

| Hamilton’s Ranch (b c d) | 3.98 | 55.35 | 35.93 | 2,978 | |

| Colfax Spring, Elwell’s (b c) | 2.55 | 57.90 | 33.38 | 3,022 | |

| South Fork Tuolumne, Lower Bridge | 0.93 | 58.83 | 32.45 | 2,654 | |

| Hardin’s Ranch (c) | 4.39 | 63.22 | 28.06 | 3,396 | |

| South Fork Tuolumne River, Upper Bridge | 1.37 | 64.59 | 26.69 | 3,420 | |

| Crocker’s Ranch (b c) | 3.34 | 67.93 | 23.35 | 3,970 | |

| Hodgdon’s Ranch (b c) | 2.00 | 69.93 | .... | 4,506 | |

| Tuolumne Big Tree Grove | .... | 74.37 | 16.91 | 5,794 | |

| Crane Flat (b c) | 1.00 | 75.37 | 15.91 | 6,054 | |

| Tamarack Flat | 5.07 | 80.44 | 10.84 | 6,234 | |

| Gentry’s (deserted) | 2.81 | 83.25 | 8.03 | 5,627 | |

| Junction of Big Oak Flat and Coulterville Roads | 4.37 | 87.62 | 3.66 | 3,949 | |

| Leidig’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 2.59 | 90.21 | 1.07 | .... | |

| Cook’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 0.30 | 90.57 | 0.77 | .... | |

| Barnard’s Hotel, Yo Semite Valley (a b c d) | 0.77 | 91.28 | .... | 3,934 | |

|

RECAPITULATION. |

|||||

| By railway | 133.05 miles. | ||||

| By carriage road | 91.28 ” | ||||

| ————— | |||||

| Total distance | 224.33 miles. | ||||

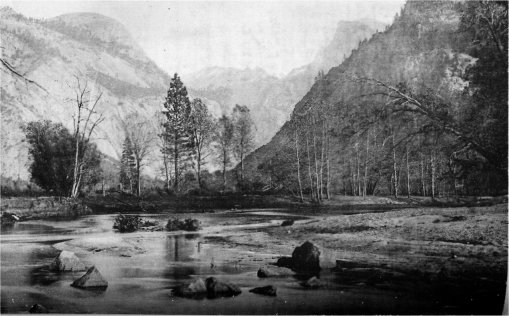

It is a superincumbent mass of volcanic trap that is supposed to have commenced its outpour near Shaw’s Flat, Tuolumne County; and, flowing into the channel of an old liver, followed its sinuous

|

| From Near Byrne’s Ferry. |

| TABLE MOUNTAIN. |

Many years ago some very rich auriferous gravel was found in the old liver bed underneath this singular volcanic deposit, and tunnels were run into it in every direction for the purpose of “tapping” the paying strata, (one of which was driven nine hundred feet through solid rock, and upon which three thousand seven hundred and fifty-six days labor were expended, additional to the cost of tools, blasting powder, etc.). How far these enterprises became remunerative is still wrapped in mystery; but sufficient information was allowed to escape to induce a numerous following of such examples.

After crossing the Stanislaus River our road winds gradually up the hill, whence fine views are obtained of that picturesque stream, and the numerous broken walls and bolder points of Table Mountain, among which Goodwin’s vineyard is most charmingly situated. Just before arriving at the entrance gate, however, we shall find the portrait of a Chinaman and his pack, upon their travels, painted upon a sign, containing this inscription—ME GO CHINESE CAMP—3 MILE ONE HALF. Now

Is a beautiful orchard and vineyard, fenced in mainly by volcanic bombs from Table Mountain, by which it is surrounded. Its well kept and weed-free grounds bespeak a becoming pride in their owner; and the temptingly bright oranges, luscious peaches, large and delicious grapes, pure home-made California wine, and the refreshing shade of umbrageous fig-trees, are suggestively inviting of a brief yet delightful visit. From the ridge beyond this a large, plain-like country, once covered with miners, stretches far away in every direction, on one side of which stands

Now it must not be supposed that the name found to belong to this once prosperous mining settlement implies that it is in the exclusive possession of natives of the Flowery Kingdom. Far from it, inasmuch as they are now largely in the minority. It is true, however, that nearly every mining town in California has a liberal representation of this class, and it is also true that the number found here in early days was far in excess of that generally found elsewhere; as it was a kind of head-quarters, especially on Sundays, for all Chinamen living within a radius of many miles. This gave the town its name.

| |

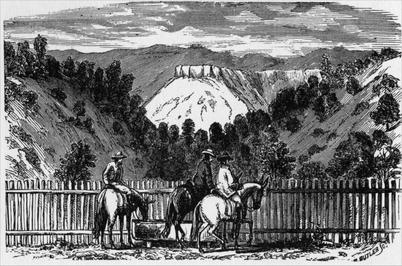

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| Wall of Table Mountain. | |

| (See page 313.) | |

Every village, town, or city in California, moreover, wherein the Chinese congregate, has its “Chinese Quarter.” They never attempt, socially, to intermix; and, unlike other nationalities, a Chinaman never drops his distinctive habits, manners, customs, dress, or manner of living, to adopt those of a people by whom he is surrounded. A Chinaman, therefore, is always a Chinaman, no matter where he may be. His contract with one or other of the

|

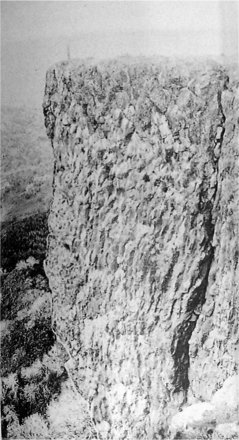

| A CHINESE COUPLE. |

|

| CHINESE FEAST TO THE DEAD. |

Whatsoever the Chinese may believe about God, they hold to the idea, whether they carry it out in practice or not, that the principal duty of man is to perform kindly services to each other, upon earth, and thus bespeak the personal good offices of their friends, especially of their parents, in the hereafter. A little of this kind of philosophy incorporated into the Christian system, would not be (as an English gentleman once expressed himself) “half bad.” Let us try a few good heavy doses of it as an experiment. Their “Feast to the Dead” probably originated in this idea, as, according to Mr. Williams, in his book upon the Middle Kingdom, they thus address the departed at the grave: “My trust is in your divine spirit. Reverently I present thee five-fold sacrifices of a pig, a fowl, a duck, a goose, and a fish; also an offering of five plates of fruit, with libations of spirituous liquors.”

When the Indians in California first saw the Chinese, there arose a dispute among the former as to the country to which the latter belonged, some contending that the Chinese were an inferior race of Indians from beyond the sea; and others, with equal pertinacity, asseverating that their eyes and facial expression were utterly unlike the Indians; and that, therefore, there could be no tribal relationship between them. This question they all determined should be effectually settled, and at once; and as they were agreed upon one point, viz., that if the new-comers were Indians, they could all swim; a water test was accordingly accepted as thoroughly satisfactory and conclusive to both parties.

When the spring snows were rapidly melting, and the angry streams were booming, a tree having been fallen across by which to form a foot-bridge, at an understood signal between the contestants, they met a couple of Chinamen upon this bridge; and, pushing them into the angry current, drowned them both! It is stated that this was a perfectly demonstrative settlement of the doubtful point between the contestants, and decided that Chinamen were not Indians! but it is not stated, authoritatively, that this process of determination was equally satisfactory to the Chinamen?

Owing to convenience of location Yo Semite bound passengers, as well as many others, generally tarry for the night at Chinese Camp, where they will find a brick hotel, clean beds, attentive service, and an obliging, wide-awake landlord, in the person of Count Solinsky, who has been Wells, Fargo & Co.’s express agent here for over thirty-five years. Then there are numerous stores, and one of the best wheelwright shops to be found in any country. Here, too, once lived the large-hearted and gifted physician, Dr. Lampson, whose genial face, so sadly missed by old-timed friends, will never be looked upon again.

Leaving “the cloud-capped towers and gorgeous palaces” of Chinese Camp behind us, our journey lies over rolling hills and flat ravines to the western side of Wood’s Creek, down which our well-graded road winds and turns, affording grand views of a wildly picturesque country in every direction, until we reach the Tuolumne River.

Formerly our course lay past Jacksonville, where its resplendent oaks gave acceptable shade while watering the horses, and for having a pleasant chat with one of its oldest pioneers, whom everybody familiarly called “Dave Ackerman.” This little village is supported, mainly, by river mining (mostly monopolized now by Chinamen) and the placer diggings of Wood’s Creek. Within a stone’s throw of the hotel was “Smart’s Garden, where once grew the earliest and finest of fruit; but which is now a desert waste, owing to its having been “worked out” by Chinese miners, for the rich placers of gold found there, and which, following the course of all gold dug out by these people, was exported to China. A short distance above this, Keith’s Orchard and Vineyard, one of the best cultivated in the State, and producing some of the choicest of fruit, were passed; and a mile farther on, the river was crossed by the Steven’s Bar Ferry. Now all this is changed, through the enterprise of Mr. J. R. Moffitt, who has had a splendid combination truss bridge thrown across the Tuolumne River Cañon, near Jacksonville, capable of supporting a weight of one hundred tons. This is called

It is three hundred feet in length (having a single span of one hundred and sixty-five feet), twelve feet in width, is fifty feet above low water mark; and its floor is six hundred and fifty feet above the sea. As we stand upon this we are for a moment at a loss which to admire most, the skill and pluck of its builder and owner, or the beautiful scenes to be witnessed from it on every hand. When we see how a broad road has been hewn out of the mountain’s side, and in all its turnings and windings preserved its uniformity of breadth and excellence; and then note how the chasm forming the river’s channel has been spanned by so fine a structure, we are ready to accord due and admiring credit to the originator of the undertaking, and yet not forego the pleasure of looking at the beautiful scenery. By the commodious and comfortable residence erected near a deliciously cold spring, it would seem that Mr. Moffitt expects to make his permanent home in this wild cañon.

After relieving one’s conscience concerning the bridge, the road, and their builder, a clearer outlook can be had of the country, and a concise summary of the whole will be embodied in Mr. John Taylor’s expressive sentence concerning it: “Skirting the Tuolumne River for three miles, the scenery becomes picturesque in the extreme, the grand panorama ever changing, so as to keep tourists and lovers of nature’s pristine grandeur in one continual ecstasy of delight.”

Leaving the main stream our course is now up one of its tributaries, for three and a half miles, known as Moccasin Creek; past vineyards, mines, and miners. This entire section becomes noteworthy from its prodigality in children’s faces, seen at the doors and windows of its humble dwellings. One family numbers thirteen, another only eleven, and so on, exclusive of their fathers and mothers! Soon after crossing the bridge we come to Newhall and Culbertson’s Vineyard (for although the former has passed home to the spirit-land, the name is still retained in the firm). This is another of those wayside tarrying places where fruit of the finest quality is in abundance, and where we can obtain a glass of the most delicious white wine to be had in any portion of the State, It is but simple justice to these people to say that their charges are not only very reasonable, but always low. Here the altitude above the sea, as given by the U. S. (Wheeler’s) Survey, is nine hundred and eighty feet.

For the next two and a quarter miles our road is on the side of a mountain, covered with a dense mass of shrubbery, among which will be found manzanita, buckeye, mountain mahogany, pipe wood, Indian arrow, granite wood, and numerous other kinds; all of which, if cut in the proper season,—November to March—are hard and useful furniture woods, susceptible of a very high polish.

You will think this quite a mountain climb—and it is. It will be well, however, to bear in mind that, before commencing the descent toward Yo Semite, we have to attain an altitude of nearly seven thousand feet from our starting point; we must, therefore, commence ascending somewhere, and why not here? It will be a task upon our patience, perhaps, but as it seems to be a trial of both wind and muscle to the horses, we may surely console ourselves with the thought that we can stand it—if they can. Up, up we toil, many of us on foot, perhaps, in order to ease the faithful and apparently overtasked animals, which puff and snort like miniature locomotives, while the sweat drops from them in abundance. In two and a quarter miles there is a clear gain in altitude of one thousand five hundred and seventy-eight feet, between Culbertson’s Vineyard and Priest’s Hotel.

One quiet evening, in the height of summer, after the sun had set, and the deep purple atmosphere peculiar to California had changed to somber gray, we (the passengers) were wending our way up the mountain on foot, and a little ahead of the stage, when a rustling sound, just below the road, startled us with its singular and suspicious distinctness, and dark shadowy forms were seen gently threading their way among the bushes. Our hearts beat uncomfortably fast, and we instinctively felt for our revolvers, but they were in the stage! It should be told that at this time numerous robberies had been committed upon the highway by Joaquin, Tom Bell, and their respective gangs. “We are caught,” whispered one. “They will rob, and perhaps murder us,” suggested another. “We can die but once,” bravely retorted a third. “Let us all keep close together,” pantomimed a fourth. “Who goes there?” loudly challenged a fifth. “A friend,” exclaimed the ring leader of a party of miners who were climbing the steep sides of the mountain just at our side, with their blankets at their backs, all walking to town, and who had caused all our alarm; and as he and his companions quietly seated themselves by the road-side, they commenced wiping off the perspiration, and gave us cordial salutation in good plain English. “Why, bless us, these men, who have almost frightened us out of our seven senses, are fellow-travelers!” “Couldn’t you see that?” now valorously inquired one whose knees had knocked uncontrollably together with fear only a few moments before. At this we all laughed; and the coachman having stopped his stage, said, “Get in, gentlemen”; and we had enough to talk of and joke about until we reached Priest’s Hotel, at the top of the hill.

Travelers in many lands have made frequent confessions to the writer, that this unpretentious wayside inn is among the most comfortable and enjoyable they have ever found in any country. Could commendatory volumes written upon it therefore say more? Many, many times have I tested it, and can both conscientiously and emphatically indorse every sentiment uttered in its praise. For although it will not, I trust, be deemed out of place to say, in all kindness, that no traveler should expect to find meals and accommodations in the mountains of California equal to those of the Palace Hotel, the Grand, the Baldwin, the Occidental, or the Lick House of San Francisco, no one will leave this hospice without carrying away with him the conviction that these people are among the too limited number of those “who know how to keep a hotel;” and regretfully riding away from its hospitable door, leave the best of good wishes behind them. What more then can be said?

Now Priest’s at one time had a very remarkable dog (there is no doubt about that fact), which writers have accredited with the wonderful intelligence of knowing the exact time the upward-bound passengers were due for dinner; when he would start off with a bound down the hill, and, meeting the stage, would look steadfastly at the inside for a few moments, as though counting the number of people to be found there, and then scamper back up the hill. Instead of lying down in front of the hotel (his usual and favorite pastime, as well as that of other dogs), he would deliberately make for the poultry yard; and, seizing the youngest and plumpest of its tenants, would carry it at once to the cook, repeating this until the requisite number was provided! Now, it might seem to be a wanton, and, perhaps, an envious act on my part to attempt to destroy the effect of a good story by questioning its reliability in the smallest degree; yet, I cannot resist the temptation of submitting, whether or not the tenderness, juiciness, and flavor of the well-cooked chicken found upon the table, might not be somewhat in conflict with placing implicit confidence in that statement? But this I do know, that he would at any time, unharmedly, seize any fowl pointed out to him, and take it direct to his master.

The commanding view from the porch, and especially that from the hill at the back of the house, not only presents the broad valleys below, with their glinting streams, and clumps of oaks, but the bold outline of the Coast Range bordering the Pacific Ocean, and all the intermediate landscape. Frequently, too, the whole country seems flooded with billowy clouds, over the tops of which peaks and mountain ranges stand boldly out in the transparent atmospheric strata above them.

| |

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| The Domes of Yo Semite. | |

When leaving Priest’s we must not omit to notice the evidences of mining on every hand, even if we forget the unpleasant fact that a miner’s labors invariably bring desolation to the landscape. Nor must we pass unseen the sturdy, branch-lopped, and root-cut veteran trunk of a noble and enormous oak, Quercus lobata; some eleven feet in diameter, now prostrate, on our right; as it was from this once famous tree that “Big Oak Flat,” the village through which we pass, and the route, received their names. Then, however, its immense branch-crowned top gave refreshing shadow to the traveler, and beauty to the scene. We fear that many a year will have made its faithful record before our virtues become sufficiently Christian to confess personal forgiveness to those who committed, or even permitted, the vandal act of its destruction. We take real comfort in the thought that its storm-beaten, dead, limbless, and prostrate form must daily administer stinging reproofs to every one whose act, or silence, gave sanction to the deed.

As we spin along among pines and firs, the deliciously bracing “champagne atmosphere” (as a lady friend so naively expresses it), is quaffed with a delightful and thrilling zest that makes itself felt through every nerve tissue of our being. Even the brief delay at Groveland (a bustling little mining town) to change the mail, only postpones the pleasure, that is renewed the moment we advance.

The gardens, vineyards, and orchards that are passed only add agreeable variety. But, speaking of orchards; at Garotte (such name-givers deserve to be garroted!), the last mining town passed on the journey (there are several), let me caution you against stopping at Chaffey and Chamberlain’s (two affectionate and noble-natured old bachelors who have lived and mined together for over thirty years); for the large and luscious fruits they take so much pride in producing will be sure to tempt you to eat again (and so soon after leaving Priest’s, you know), and it is a long way to the doctor’s! Before leaving here, let me call especial attention to two species of beautiful oaks; one is the weeping white oak, Quercus lobata; and the other a live oak, Quercus chrysolepis, as they are among the best representatives of that family that I have ever seen, anywhere.

A short ascent up a somewhat steep hill, brings us to the ups and downs of a ridge road, with timber and shrubbery on both sides. The large ditch we cross several times is that of the Golden Rock Water Company, constructed for the purpose of supplying the mining towns below with water for mining purposes. This work will be seen at different times until we pass the “Big Gap”; where still lie the burnt fragments of a flume, once the pride of its engineers, as the finest wooden structure of the kind in the State, with a height of two hundred and sixty-four feet above the Gap, and a length of two thousand two hundred feet; costing the snug little amount of pocket-change of eighty thousand dollars. A strong wind one night told the sad story, that “the best laid plans of mice and men gang aft agley,” and made it a total wreck. Now, a large iron tube placed upon the ground answers the purpose of the flume. This only cost some twelve thousand dollars. An immense deposit of “tailings” at the “Little Gap” we are now passing, with the water-torn banks of a gravelly hill standing near, tell that the work of hydraulic mining has but recently ceased here.

A little beyond this we come to a bright little home-like spot called “Hamilton’s”; and, while the horses are being changed, the opportunity will be afforded of making the acquaintance of its owners. Mrs. Hamilton, who is the presiding genius of the household (her husband probably being busy on the farm), can cook as nice a meal as almost any one, and by adding a little spice of praise to this or that upon the table (not to the cooking, remember, as she is too modest for that), induce you to find an appetite to eat it; but as the stage arrangements may not allow of such a test, she will be sure to have some kind of fruit to offer; and, if that is out of season, has always a kindly word, and a refreshing glass of water to give you. Try it.

As we advance it is evident that the timber becomes larger and the forest land more extensive. The gently rolling hills begin to give way to tall mountains; and the quiet and even tenor of the landscape changes to the wild and picturesque. An occasional deer may shoot across our track; or coveys of quail, with their beautiful plumage and nodding “topknots,” whirr among the bushes. The robin, and meadow-lark, and oriole may prove to us that they still have a love and a voice for music; and the “too-coo“-ing of the dove tells us that its sweetly mournful voice “is still heard in our land.”

But who, in feeble language, can fully disclose the grandeur of the scenery that opens before us a short distance east of the Big Gap? When the painter’s art can build the rainbow upon canvas so as to deceive the sense of sight—when simple words can tell the depth and height, the length and breadth of a single thought—or the metaphysician’s skill delineate, beyond peradventure, the hidden mysteries of a living soul—then, ah! then, it may be possible.

Deep down in an abyss before us is a gulf—a cañon—of more than two thousand feet. The gleaming, silvery thread, seen running among bowlders, is the Tuolumne River, a hundred feet in width. Its rock-ribbed sides, in places, show not a vestige of a tree or shrub. In others, its generous soil has clothed the almost perpendicular walls with verdure. As the eye wanders onward and upward, it traces the pine-clad outlines of distant gorges, whose tributary waters compose and swell the volume of the stream beneath us. To the right, surrounded by noble trees, can be discerned a bright speck—it is a water-fall a hundred feet in height and thirty feet in width. In the far distance, piercing the clouds, the snow-covered peaks of the Sierras lift their glorious heads of sheen, while a beautiful purple haze casts its broad, softening mantle over all. Our road, shaded by lofty pines and umbrageous oaks, and cooled by a delicious breeze, lies safely near the edge of the precipice; the whole panorama rolled vividly out before us. It is such scenes as this that introduce such grateful changes to such a journey.

Just beyond this we arrive at Elwell’s, Colfax Springs; another pleasant little wayside house, and soon thereafter cross the south fork of the Tuolumne River, at the lower bridge; then wind our way up a long hill, over to Hardin’s Ranch; and after recrossing the south fork by the upper bridge, ascend another long hill, and are then at the justly famous lunch house of

The pretty little garden, bright with flowers, bespeaks a cheery welcome almost before we alight, and the look of cleanliness everywhere apparent prepares the way for an appetizing meal. There is no hurry, no excitement; a quiet wash, followed by the quiet announcement that “lunch is ready,” and we are ushered into a room where a most elegant repast awaits us. It is but simple justice to Mr. and Mrs. Crocker, to say that their table is loaded with creature comforts, and in such abundance and variety that even the most delicate or fastidious can find something they can relish and enjoy. There are but few places upon earth, if there are any, where a more excellent refection can be obtained, or one be more pleasantly served.

Still our course is upward, until we have reached a long stretch of elevated table-land that, for timber, is not excelled in any portion of the State. Large sugar-pine trees, Pinus Lambertiana; from five to ten feet in diameter, and over two hundred feet in height, devoid of branches for sixty or a hundred feet, and straight as an arrow, everywhere abound. Besides these there are thousands of yellow pines, Pinus ponderosa; Douglas firs, Abies Douglasii; and cedar, Libocedrus decurrens; that are but little, if any, smaller or shorter than the sugar-pines. These forests are not covered up with a dense undergrowth, as at the East, but give long and ever-changing vistas for the eye to penetrate.

Mr. George McQuesten, of East Boston, measured one of the prostrate sugar-pines in this grove, with the following results: Circumference, three feet from base, twenty-one feet ten inches; fifty feet from base, fourteen feet six inches; one hundred feet from base, eleven feet three inches; one hundred and fifty feet from base, eight feet six inches; two hundred feet from base, four feet three inches; two hundred and nine feet from base, two feet three inches. This might have been from twenty feet to forty feet higher when standing. It contained nineteen thousand five hundred and sixty running feet of lumber, or one thousand seven hundred and eighty cubic feet, after deducting ten percent for saw scarfs. Value in Boston, less cost of carriage and sawing, $195. While thinking, and almost dreaming of forest scenes, we have arrived at

These are of the same genus, Sequoia gigantea, as those of Calaveras, Mariposa, and other groves; many fine specimens of which stand by the road-side, or can be readily seen without leaving the coach; but none can realize their large proportions without standing up against one, or walking around it. Besides, it rests us to walk a little, and adds much to the interest to touch their enormous sides. There are about thirty in this group, well proportioned, and excellent representatives of the class. Two of them which grew from the same root, and unite a few feet above the base, are called the “Siamese Twins.” These are about one hundred and fourteen feet in circumference at the ground, and, consequently, about thirty-eight feet in diameter—of course including both. The bark has been cut on one side of one of them and has been found to measure twenty inches in thickness. Near the “Twins” there are two others which measure seventy-four feet around their base.

| |

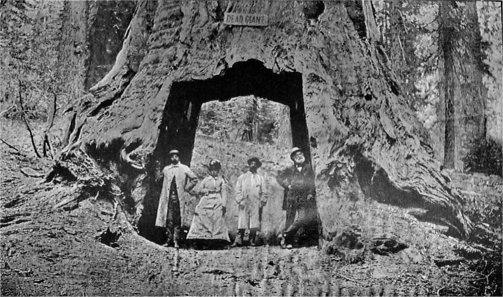

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Engraved by Heliotype Co., Boston. |

| THE DEAD GIANT (31 feet in diameter). | |

One of the most striking examples of the extraordinary growth of this species is found in the immense stump called “The Dead Giant,” for, although fire has entirely denuded it of its bark, and largely reduced its proportions, it is even now thirty-one feet in diameter. By the earthy ridges that form around almost every forest tree, it is plainly evident that this, at one time, must have had a circumference of over a hundred and twenty feet. For the purpose of enabling visitors more easily to apprehend its enormous size, a “tunnel” has been cut through it which is ten feet in width by twelve in height, and through which the stage coach passes when either going or returning to Yo Semite. There is no more convincing evidence of size than this in either of the groves—if we except the “Stump” at Calaveras. Within a few yards of this grows one of the finest and most symmetrical representatives of this wondrous family.

“Excelsior” being our motto, we shall soon reach “Crane Flat.” These flats are grassy meadows, interspersed among the mountain districts, and are generally the heads of creeks or rivers, being almost always “springy.” Of late years they are fed off by bands of sheep, brought from the plains when the feed there has become short or dry. Running upon or over trails, they are apt to obliterate all traces of the traveler’s course, and where a short turn is made, great care is needed, by the inexperienced, to prevent being lost. Crane Flat, kept by Mrs. Gobin, was once celebrated for the excellence of its meals, when horseback riding was the only method of reaching Yo Semite. Its wrecked buildings now tell their own story of the effects of deep snow. Here the stage possibly changes horses, and thirsty passengers take a drink with Mr. Hurst (whom nearly all the old-timers affectionately call “Billy Hurst”).

One of the obstacles to be overcome for early season travel to Yo Semite on the Big Oak Flat Route was the deep snow belt of some ten miles, lying between the Tuolumne Big Tree Grove and Gentry’s; the highest part of the road being seven thousand feet above sea level. Here snow would be from six to twenty feet deep. To shovel all this out was a herculean and expensive undertaking, while building walls of snow that reached far above the tops of stage coaches. Then, the glaring sheen of the sun shine on a white surface was exceedingly trying to the eyes of the shovelers, and frequently brought “snow-blindness;” attended with the discomfort, and unhealthiness, of working in wet snow that chilled their lower limbs while the entire upper part of their body was steaming with perspiration. These difficulties, therefore, must be conquered by other means. But, how? That query brought forth another: Why not put

This experiment was accordingly tried, and proven to be most eminently successful. A glance at the accompanying engraving will give an idea of their form, and the manner of their use.

|

| HORSE ON SNOW-SHOES. |

The horse snow-shoe is made of one inch ash plank, thirteen inches long by eleven wide. It is rounded at the corners to prevent striking, or chafing; and a hollow is cut at the back to allow full play to the shoe, without cutting or bruising the leg. There are three holes mortised in the upper surface of the snow shoe, the exact size and shape of the horse-shoe calks, and which are inserted therein, to keep the foot in its place, and give solidity to the tread. To make the snow-shoe clutch the horse’s hoof snugly, well-fitting flat bands of Norway iron, lined with thick india-rubber cloth, are placed across and clip it; these meet in the center of the foot, where they are brought together by an adjustable screw-bolt; the lower ends of these bands pass through the snow-shoe, to which they are fastened by a bolt and nut, and become assistant tighteners of the clip. On the under side of the snow-shoe, and additional to the bolt and nut, an irregular and almost heart-shaped flange of steel, about half an inch in depth, is riveted, nearly covering the bottom of the shoe, and which prevents sliding in any direction, while adding to its strength. To prevent the snow-shoe from splitting, a fine bolt is run through each end.

When every foot is equipped with one of these, each of the four horses forming the team is ready for the start. Now the interesting essay of using them commences. Each animal seems to have an intuitive knowledge of what they are for, as of the duties expected of them; for, carefully lifting the foot higher than he would under ordinary circumstances, with a somewhat rotary and semi-oscillatory movement, he throws the foot forward, and one shoe over the other, with such intelligent dexterity that they rarely touch each other; and invariably manages to take the front snow-shoe out of the way, before setting the hind one in its place. There is no confusion or even awkwardness in their use, although there is in appearances when seeing horses in such ungainly-looking appendages.

I speak from personal observation, after several delightful sleigh rides over that snow-belt with Joe Mulligan (we all know him by that unpretentious and familiar cognomen only), whose patient care, skill, and watchful management of his horses, under the most trying circumstances, occasionally, elicited my warmest admiration. The gait uphill was a quiet walk, at the rate of about three miles an hour, performed with no more excitement or friction than a heavily-laden team would use, in moving its load upon a level road. Downhill we frequently took a short trot, and which, like the walk uphill, was accomplished without clumsiness. The time generally consumed in crossing the ten miles of snow was about three and a half hours.

To illustrate how much such pioneer path-finders over snow have sometimes to endure, it is only necessary to sketch a single “first trip of the season.” There were three strong men, Mulligan, Billings, and Wood, who left Crocker’s early one April morning for Crane Flat, some six miles distant, with a coach and four good horses, sleigh, horse snow-shoes, shovels, axes, ropes and other desirable accessories for such an enterprise. Deep new snow had made progress exceedingly slow and difficult. At two o’clock on the following morning they succeeded in reaching the point designated, but no signs of buildings were visible in all the snowy waste. They could see large hillocks of snow, but no place wherein to shelter themselves and horses. Finally, as day was breaking, they found the bearings of the stable door; and, weary as they were, commenced shoveling away the feathery element in front, in order to give their tired animals a place of refuge, and necessary food. An entrance to the stable was eventually secured; but, as the snow was some eighteen feet in depth, and a passageway down to the floor would be the work of many industrious hours, they led each horse, separately, as near as possible to the opening effected; when, by fastening one rope around the head, and another to the tail of each animal, they lowered them into their quarters for the night, by sliding them down over the snow; and, being too tired to eat, the men rolled themselves up in their blankets, and forgot the fatigues of the day in refreshing sleep.

About ten o’clock a. m., they found themselves outside of their breakfasts (as they expressed it), and were again upon the snow—one might have said the road, but that lay from sixteen to twenty feet below the surface. Spending this day also in wearying and unflinching effort, they only broke the way to the top of the ridge, some two and a half miles distant, and then returned to their inhospitable quarters at Crane Flat for that night also. On the following day they again, undauntedly, set their own and horses’ faces towards Yo Semite, still some sixteen miles distant. Its mountain peaks, and cheery open fire-places, far down out of the snow, became delightfully stimulating day-dreams to them; and, about nine o’clock p. m., Tamarack Flat had been gained, and five additional miles overcome, leaving eleven only to be conquered. Here, also, the snow was as deep as at their stopping-place of the two preceding nights; and similar experiences in snow-shoveling, and horse-sliding down to the stable floor, had to be indulged in until long after midnight. Hungry as wolves, most of the remaining portion of the night was spent in cooking and eating, and the residue only devoted to renewing slumber.

Notwithstanding these protracted wrestlings with their white-faced enemy, their motto, “There’s no such word as fail,” was not only inscribed upon their determined faces, but was written deeply in their wills and hearts; and as soon as a passage-way out for their horses could be dug through the snow, and the snow-shoes were adjusted to the animals, they made the crisp air ring with the shout, “Ho! for Yo Semite,” and again started forward. On reaching Cascade Creek Bridge they found the snow piled upon it as deep and steep as the roof of a Swiss cottage; but, with shovels in hands, as defiant of obstacles as ever, they dug a pathway across it, led the horses over in single file, pulled over the sleigh with ropes, and again set out for the Valley. Before noon they reached the lower edge of the snow-belt, and the solid earth; where they left their sleigh, and horse snow-shoes, and by three o’clock p.m. were safely at the hotels at Yo Semite. Pluck, human endurance, and determination, had conquered a victory. All honor to such noble and unremitting exertion.

Nor were these by any means the only efforts that were made to overcome the elemental forces in antagonism to early tourist travel to Yo Semite; inasmuch as Mr. A. H. Washburn, the energetic superintendent of the Yo Semite Stage and Turnpike Company, and assistants, had pressed every available man into service on the southern side of the great chasm; to shovel snow, chop out limbs and trees that had fallen across the road, drain and repair the road-bed, rebuild road walls and bridges, and perform all sorts of other and similar services, before coaches could safely and expeditiously carry passengers into the great Valley. Those who make the journey later, and find everything just as it should be, can form but a very inadequate idea of the difficulties that have been surmounted, the labor performed, and money expended in these necessary enterprises.

Two and a half miles above Crane Flat the highest portion of the road is reached, being seven thousand feet above sea level; and which, lying upon the dividing ridge which separates the waters of the Tuolumne River from those of the Merced, the outlook from it is strikingly bold. From this ridge magnificent views of distant landmarks, and the snow-covered peaks of the Sierras open at brief intervals before us; while timber-covered ridges and gorges stretch farther and farther away to the verge of the distant horizon; with an occasional mountain of verdureless rock, standing gloriously out as if to defy the further encroachments of those evergreen masses of pines. There does not seem to be a foot of ground over which we are passing that has not some novelty to charm us.

The apparently omnipresent forest overarches our way; and beautiful firs, Abies concolor and A. grandis, the magnificent pines, P. Jeffreyi, P. ponderosa, and P. Lambertiana; and “tamaracks,” Pinus contorta, stand sentinel guard on every hand; while patches of stunted manzanita, Arctostaphylos glauca, with its evergreen leaves and fragrant waxy-like blossoms; and several different species of Ceanothus literally loading the air with their perfume, and brightening the landscape with their plumes of white and blue, attract our attention, until, by a gentle declivity, we pass Tamarack Flat, down to Cascade Creek, where the water is dashing itself to atoms, that scintillate and sparkle in the sun; and arriving at Gentry’s, commence the descent of the mountain-side on the Yo Semite Turnpike Road. Looking down upon the great cañon of the Merced River from this point, there opens before us one of the most magnificent and comprehensive scenes to be found anywhere; as not only can the numerous windings of the river be traced for miles, as it makes its exit from the valley, but its high bluffs and distant mountains stand boldly out. At another turning of the road we look into the profound and haze-draped depths, and up toward the sublime and storm-defying heights, with feelings all our own, and behold Yo Semite.

Before closing this chapter it becomes my pleasant duty to chronicle the historical fact, that the Big Oak Flat and Yo Semite Turnpike Road Company was the first ever organized for the purpose of extending wagon road facilities beyond the settlements in the direction of the Yo Semite Valley. When the great overland railroads, the Central Pacific and Union Pacific, were nearing completion, in 1869, the question was very properly considered of providing easier transit for the large class of visitors that might be attracted hither; and who, unlike old Californians, were unaccustomed to horseback riding. In this emergency the residents of Big Oak Flat and vicinity were waited upon, and as a business lethargy had fallen upon that district, in the hope of its revival somewhat by such an enterprise, these people formed a company; and the road was completed that year to Hardin’s, leaving but about twenty-five miles to be traversed on saddle animals. Encouraged by the liberal patronage bestowed, this was extended the following year to Hodgdon’s; and, during the next two years, to Gentry’s, the northwestern corner of the Yo Semite Grant. As the company was not financially strong enough then to complete it to the valley, this became the terminus of the road, and so continued until its completion to Yo Semite, July 17, 1874, on which occasion over five hundred persons passed over it, in a kind of triumphal procession.

Next: Chapter 23 • Index • Previous: Chapter 21

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/22.html