| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Indians >

Next: Chapter 25 • Index • Previous: Chapter 23

|

I would not enter on my list of friends

(Though graced with polish’d manners and fine sense, Yet wanting sensibility) the man Who needlessly sets foot upon a worm.

—Cowper’s

Task, Bk. VI.

|

|

To tell men that they cannot help themselves is to fling them into recklessness

and despair.

—Froud’s

Short Studies on Great Subjects.

|

|

Be noble! and the nobleness that lies

In other men, sleeping, but never dead, Will rise in majesty to meet thine own.

—Lowell’s

Somnet, IV

|

Shortly after taking up our permanent residence in Yo Semite an Indian presented himself one morning, when the following colloquy ensued:—

“You li-kee Indian man wor-kee?” “Are you a good worker?” “You no li-kee me, you no kee-pee me, sab-be (understand)?” “Well! that seems fair enough. How much-e you want, you work e one day?” “One dol-lar I tink wa-no (good).” “All right. What’s your name?” “Tom.” “Well, Tom, you come work-e to-morrow morning; sa-be, ‘to-morrow’ morning?” “Seh (Si, in Spanish), me sa-be.” “Seven o’clock?” “Seh, me sab-be.” “You better come before seven, Tom, then you get-tee good breakfast; Indian man work-e better, he eat-ee good breakfast.”

At this latter proposition Tom’s somewhat somber face lighted up with a glow of child-like pleasure; and, when the following morning came, he was on hand both for his meal and labor also. Finding him to be the most faithful Indian worker that I had ever seen—for, as a rule, Indians do not take kindly to steady labor—after some ten or twelve days, as we were becoming short of desirable articles for the household, and our packer was unwell, questions were put and answered thus: “Tom, you sa-be pack ing?” “Po-co” (little). “You sa-be Big Oak Flat, Tom?” “Seh. Me sab-be Big Oak Flat.” “You li-kee go Big Oak Flat, get-tee some sugar, some flour, and such things?” “You li-kee me go, I go.” “All right, Tom, you get-tee five horses-sa-be ‘five’” (counting the number on my fingers). “Seh. Me sab-be.” “Four you pack, one you ride, sa-be?” “Seh. Me sab-be.”

Promptly at seven o’clock Tom was on hand, with the horses; when I handed him a letter, and explained to him that that paper would tell the store-keeper at the settlements the kind and quantity of articles wanted, and which would be handed to him for packing nicely, and bringing safely to us. Then, laying five $20 pieces, one by one, upon the palm of his hand, I said to him, “Tom, you ta-kee these five $20 pieces to Mr. Murphy, storekeeper, at Big Oak Flat (as Mr. Murphy no sa-be me), and they will pay for what he give you to bring us.” “Seh. Me sab-be.” Tom’s eyes sought mine with bewildering yet gratified astonishment (while they filled with tears); as though apparently questioning the possibility that I could trust him, an Indian, with five horses, and as many $20 pieces. He seemed to have suddenly grown several inches taller, and more erect than I had ever seen him; as with an open and manly look he slowly responded, “Wa-no. Me go. Me ta-kee money. Me pack-ee sugar-flour, here.”

When Tom returned with everything perfectly straight, and in good order, he was evidently as proud and delighted as a Newfoundland (or any other) dog could have been with two tails. His face had a smile all over it—an uncommon sight in an Indian. From that time Tom was not only my friend, but a friend to every member of the family; and he took as much interest in everything as though it was his own. The confidence reposed in him had completely conquered the Indian, by making him to feel that he was a man.

A few weeks after this he wanted to pay a visit to his people, whose camp was some forty miles below; and, as he said, “eat-ee some acorn blead (bread, as they seldom sound the r) and go hab fandango” (Indian dance). It may be cause for wonder that the best of good food, when provided and cooked by white people, is only satisfactory for a time, to the Indian; he longs (not for “the flesh-pots of Egypt,” perhaps, but) for “acorn blead.” It is an apparent physical necessity to him.

Upon Tom’s return an almost uncontrollable excitement seemed to quiver through his whole frame, while the perspiration exuded from his hair, and rolled down his somber face in streams. Breathlessly sinking upon a chair, a wild, agonizing frenzy, distorting every muscle of his features; while gleams of fire seemingly shot from both his eyes, as soon as his lungs could perform their office, and his tongue and voice could find utterance, he gasped out, “Oh! Mr. H., Mr. H., Indian men come kill-ee me.” “Hullo! Tom, what on earth have you been doing, that Indians should want to kill you?” Gathering breath and effort gradually, yet simultaneously, he exclaimed, “Oh! Indian man say I kill-ee one Indian; I no kill-ee Indian man, Indian man kill-ee Big Meadows—I no go Big Meadows, I go Bull Creek. They tink I kill-ee him, though, and Indian men-five (counting on his fingers)—come kill-ee me.” “Are you sure, Tom, you no kill-ee Indian man?” “I sure I no kill-ee Indian. How I kill-ee Indian man Big Meadows—I no go Big Meadows?? I sure I no kill-ee him. You hi-de me somewhere?” “You sure you no kill-ee Indian man, Tom, eh?” “I sure I no kill-ee him.” “All right, Tom, then I hide you somewhere.”

This had been successfully accomplished but about twenty minutes when up came the five Indians mentioned by Tom, “armed to the teeth,” as the saying is, sweating and almost out of breath; when one of them inquired, in pretty good English, “Have you seen Indian Tom?” “Oh! yes, Tom was here about half an hour ago. Is there anything the matter?” “Yes, Tom killed an Indian at Big Meadows.” “Yes? Why, Tom told me he did not kill the Indian at Big Meadows; he said that some Indians thought so, but that he was not at the Big Meadows—he went only to Bull Creek.” “Yes. Tom killed an Indian man at Big Meadows; and if we find Tom we shall kill him. That is Indian fashion.” “But, Tom told me that he did not go to the Big Meadows, and did not kill the Indian there; and if you go kill Tom, and Tom did not kill the Indian, as you say, then the Sheriff of Mariposa will take you to jail, and by and by they will hang you, as they ought to do, if you kill an innocent man. You Indian men too fast, and too hot. You cool down a little. Then, when you find the man who did kill the Indian, have him taken to Mariposa; and if found guilty they will hang him and save you all the trouble. You take my advice, and don’t kill any man, especially when he may be entirely innocent of the crime with which you charge him.”

Although they took reluctant departure for the present, they evidently thought that Tom was not far away; as they were frequently seen near, and upon the lookout. In about three days after their first appearance they absented themselves, and nothing more was seen of any Indian for over a week; when two Indian women came to me and asked if Indian Tom had been there. I replied that he had—about a week ago. “So,” I suggested, as though questioning the truth of Tom’s relation, “so Tom killed an Indian at Big Meadows, eh?” “No, no, no; Tom no kill-lee Indian Big Meadows. Two Indian men see Sam Wells kill-lee Indian at Big Meadows—Tom no kill-lee him.” “Then if I see Tom I am to tell him that, eh?” “Yes, yes, I Tom’s wife.” “Oh! that is the way the land lies is it? All right, if I see Tom I tell-lee him.”

Tom was soon seen, and the case stated, when he wished me to invite them over. Asking them if they were not hungry (and it was a rare sight to see an Indian that was not), and receiving an affirmative answer, they were soon eating where Tom could catch sight of them without being seen; and in a few minutes after wards they were all walking happily together in the bright sun shine as fearlessly free and as happy as children.

When the would-be-avenging Indians made their reappearance a few days subsequent to this denouement, they acknowledged, though somewhat reluctantly, that Tom was proven to be entirely innocent of the crime; as two other Indians had seen the murder committed by another man, whose resemblance to Tom had caused the mistaken identity, that would have cost the innocent man his life, had they found him at the time of their impetuous search.

This thrilling incident very naturally made Tom’s heart warm

|

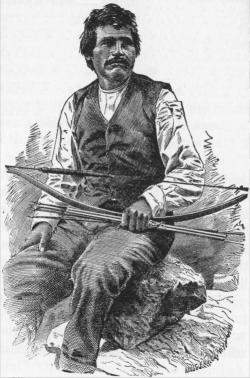

| Photo by G. Fagersteen. |

| INDIAN TOM. |

INDIAN TOM.

Owing to his many years of faithful service in our family, all of the other Indians (there being many “Tom’s”) called him “Tom Hutchings!” and as he so calls himself he evidently cannot be ashamed of it. Tom does not claim to be a full Yo Semite Indian; inasmuch as, although his mother belonged to that tribe, his father was a Mono (Pah-uta). After this, I trust not uninteresting, introduction, please allow me to present a few facts concerning

The Indian camp, and its People—Probable Numbers—Physical Characteristics—Acorns their Staple Breadstuff, How Prepared and Cooked—Kitchavi—Pine Nuts—Esculent Plants—Grass and Other Seeds—Wild Fruits—Fish—Game-Miscellaneous Edibles.

I have learned

To look on Nature, hearing oftentimes

The still, sad music of humanity;

Not harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue.

—Wordsworth.

One of the many attractive features of Yo Semite is the Indian camp, and its interesting people—the original owners and first settlers. Deplorable as the fact may be, however, there are less than twenty living of a tribe that, in 1851, numbered nearly five hundred.* [* The causes of this astonishing decrease are mainly given on pages 77, 78.] The remnant being representative of the principal customs, occupations, manner of living, habits of thought, traditions, legends, and systems of belief, not only of their own people and the surrounding tribes, but of the California Indians generally, a visit to their village, and a sight of its inhabitants, will be the more inviting and instructive. Before presenting ourselves at

As we would not willingly do them even an unintentional injustice, let us not forget that they have always been nomadic, and have continuously camped out; that any appearance suggestive of untidiness is to be attributed more to circumstances than to mental antagonism to a higher social standard. They have no neatly furnished private apartments to which they can retire, and cultivate the attractive mysteries of the toilet. Like people of good common sense they accept their position, and make the best of it. Even among our friends, those who have sought the exhilarating elixir of mountain air, or rambled far from human habitations in pathless forests, to luxuriate upon the sublime or beautiful, know how difficult it is, at such a time, to keep comfortably clean. It was an abstruse problem to Mark Twain, you remember, who had passed through sundry such experiences, to solve the possibility of the Israelites keeping half-way clean while “camping out” forty years in the “Wilderness!” And the Indians have probably discovered, that necessity has compelled this for more than as many generations. With these preliminary suggestions, let us now seek their picturesque habitations.

Their principal location is just below the old, or “Folsom” Bridge, on the north side of the Valley, about half a mile westerly of Leidig’s Hotel. The usual and most enjoyable manner and time of visiting them is during the afternoon drive, described elsewhere. Just before reaching their encampment, some singular structures, built upon posts, arrest our attention. These are

The platforms of which are about four feet from the ground. They are generally twelve feet in height, and three and a half feet in diameter. The sides are formed of bushes, interlaced and covered with pine boughs, inverted; the needles of which prevent squirrels from climbing up, yet conduct the rain down, and

|

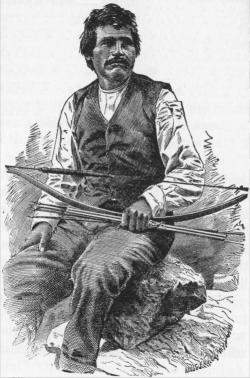

| INDIAN WOMAN GATHERING ACORNS. |

Not only in and around Yo Semite, but through all the mountain districts of the State. Nor is this peculiarity confined to those dwelling west of the great chain of the Sierras, inasmuch as those upon the eastern slope embrace the opportunity of supplementing any lack of piñons, or pine nuts (Pinus monophylla), which constitute their principal article of diet there, for acorns; oaks being almost unknown on that side of the mountains. It is a fortunate or providential coincidence, too, that whenever the piñon crop fails on the eastern slope, acorns are generally abundant on the western, and vice versa. It is not an unusual sight at Yo Semite for a single file—and all travel single file—of Mono Indians (a branch of the Pah-utas, commonly called Pi-utes), numbering from twenty to fifty, of almost all ages, and of both sexes, to pass along the Valley. They come for acorns, mainly. Nor do they come empty-handed, as the conical baskets, and discolored sacks, at the backs of their females, abundantly prove; for they are loaded down with piñons, Kit-chavi, and other articles, as presents, or for exchange. About the Kit-chavi there is more to be said hereafter.

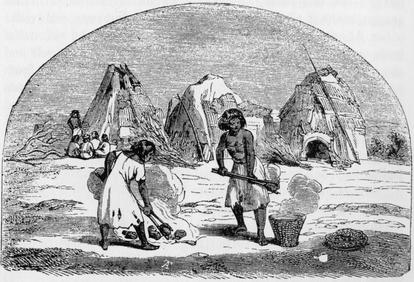

The little group of huts, constructed of cedar bark set on end, being the Indian camp, let us advance towards it somewhat reservedly, as a rude intruder is never welcome; and it requires quite an effort on their part to conquer their unpretentious diffidence and natural modesty. Remember this. After the quiet smile of welcome is given, a glance around will reveal to us that the women are all busy and fully occupied. Like many other housekeepers, their work seems never done. This one is skillfully plying her nimble fingers upon a water-tight basket; that, in deftly arranging the frame-work of one of another kind; as these people still rely entirely upon them selves for all such articles, notwithstanding the manifold contrivances brought within their reach by civilization. The woman at our left has evidently caught up the spirit of her more favored sisters, and is adroitly arranging the parts of a bright calico dress (nearly all Indians revel in bright colors); that, in repairing or turning one. Old habits are steadily, yet noticeably, passing away, and new—may we not devoutly hope better—ones are taking their places. That female with a shallow basket at her side, half filled with acorns, is dexterously prepaying them for to-morrow’s meal, by speedily setting each particular acorn on end, and with a light tap from a small pebble separating the husk from the kernel. Thus freed and cleaned, they are next spread upon a rock to dry. As these are to be fittingly prepared for human food, it may not be uninteresting to trace the different processes by which this is successfully accomplished.

First, then,

The morning meal being satisfactorily disposed of, nearly

|

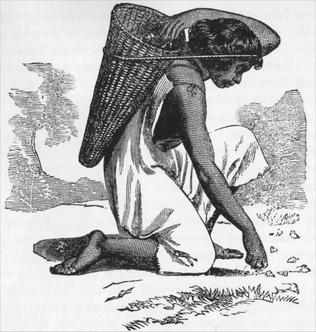

| INDIAN WOMAN CARRYING ACORNS. |

When the acorns thus pulverized are about the fineness of ordinary corn meal, as the acorn flour needs to be relieved of its bitter tannin to prevent constipation, it is carried to the nearest stream where there is an abundance of clean white sand, in which a hollow is scooped, about three feet in width, by six inches in depth, and which is patted evenly and compactly down, preparatory to a continuation of the intended process. Meanwhile other Indians have been building a fire, and almost covering it with roundish rocks from four to six inches in diameter. These are made nearly white

|

| INDIAN WOMAN GRINDING ACORNS AND SEEDS. |

The meal thus divested of its bitter principle and deleterious qualities, is ready for removal from its sand-basin to a basket. To accomplish this, free of sand, requires very careful manipulation; but, after removing all the soft, pulpy material possible, by cautious handling, without including a grain of sand, the remainder is stirred rapidly around in a conical basket, half filled with water; when the meal settles on the sides of the basket, and the sand down into the inverted cone at the bottom. In this way the whole is secured with but trifling waste of material.

It is now ready to be made into bread, or, rather, mush.

|

| INDIANS PREPARING AND COOKING THEIR ACORN BREAD. |

On the western borders of Mono Lake (whence many of the Indian visitors of Yo Semite come), there is an extensive stretch of foam forms every summer; and soon thereafter it is covered with swarms of flies; which, when they rise en masse, literally darken the air; these, “fly-blow” the foam; and, later in the season, make it alive with larvae and pupae from one end to the other. At such times every available native, young and old, and of both sexes, repairs to Mono Lake with baskets of all kinds and sizes, old coal-oil cans, and such articles; and, collecting this foam with its living tenants, repair to the nearest fresh water stream (Mono Lake water being impregnated with strong alkalies), and there wash away the foam, while retaining all the larvae and pupae. This is spread upon flat rocks to dry; and when cured, is called “Kit-chavi,” and thenceforward forms one of the luxuries of Indian food, and becomes their substitute for fresh butter!

Before participating therefore in the festivities of a morning or evening meal, this appetizing addition is made to their acorn mush-bread; when all sit, or kneel, around the unctuous viands, and with his or her two front fingers, converted for the time being into a spoon, help themselves to this unique repast, all eating from the same basket.

Wild greens, clover, gnats, grubs, and mushrooms; grass, weed, and other seeds, next to acorns, are their staples for food purposes, and the best they can command for winter consumption. To obtain these the women and children beat them into broad-topped baskets; and, after taking them to camp, clean, dry, and store them like acorns.

Bulbous grass roots, eaten raw, are a favorite food; from the digging of which, so frequently seen in early days, sprung the despised term “Digger Indians,” now so generally, and so unworthily in use to designate the lowest class of mountain Indians throughout the State. All kinds of wild fruits, excepting the wild coffee, Rhamnus Californica, are partaken of with avidity. The young shoots of the Hosackea vetch, used as greens, are considered the finest of all native vegetables.

These are eaten as meat and cooked in various ways. Some times they are caught, threaded on a string, and hung over a fire until they are slightly roasted, then eaten from the string. At others the grass is set on fire, which both disables and cooks them; when they are picked up and eaten, or stored for future use.

The most effectual method for securing grasshoppers, when they are abundant, is to dig a hole sufficiently deep to prevent their jumping out; then to form a circle of Indians, both old and

|

| INDIANS CATCHING GRASSHOPPERS

FOR FOOD. |

When the larger game is hunted, a large district is surrounded by every available Indian, and experts with the bow and arrow are stationed at a given point; when, by fire and noise, the affrighted animals are driven towards that spot, where they are killed. These general hunts take place in the fall of the year, when everything being dry is easily ignited, and when a winter supply of meat is needed. It is to this system of procuring game that so many forest trees have been burned in past years; but the sheepherder’s vandal hands, mainly, are perpetuating this in famously wanton practice at the present time. Hunting, however, is too active an employment to square with their ideas of ease and comfort; so that to comport with these, and yet secure their game, they drive it into swampy places, where they mire down and are then caught and killed.

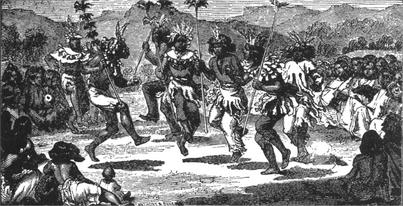

To the casual observer, a fandango, or Indian ball, is a wild, careless, free-and-easy dancing and feasting party, and nothing more. To the Indians it is a friendly gathering together of the remnants of their race, for the purpose of cementing and perpetuating the bonds of family and tribal union more closely; and at the same time to orally transmit to posterity the noble deeds and valorous actions of their ancestors.

Any particular tribe wishing to give a fandango sends messengers to all the chiefs of the surrounding tribes, to whom they wish to give the invitation; accompanied by a bundle of reeds or sticks, which indicates the number of days before it takes place; but sometimes notches are cut in a twig, or knots are tied in a string, for that purpose.

Extensive preparations are immediately entered upon for a grand feast, and everything within the limit of Indian purveyance is pressed into service; nor is it to be supposed that those giving the invitation are the only contributors, by any means; inasmuch as every attendant takes something to make up the general variety; and to add to that valuable quality in an Indian’s estimation—quantity. At such times, too, presents of blankets and other valuables are brought and exchanged.

At these festive seasons, both males and females dress them selves according to their most extravagant notions of paint and feathers. Several weeks are frequently consumed in making head dresses, and other ornaments, of shells, beads, top-knots of quails, and the heads and wings of red-headed woodpeckers. When the great day of the feast arrives, groups of Indians may be seen wending their hilarious way to the festive scene; and as many have to travel fifteen or twenty miles, the whole first day is consumed in assembling together, and gossiping over family matters. In the evening, when all are assembled, the “band” (which consists of about a dozen men, with reed whistles, and wooden castanets, with which they beat the time) begins a monotonous few-few with their whistles; while the dancers follow their leader with the castanets, and with them keep time with a perpetual hi-yah, hi-yah, until they are out of breath, when they take their seats for a rest, and listen to their orator for the occasion.

|

| [Indians at a fandango.] |

These fandangos are generally kept up for a number of days; and, as frequently happens at others much more fashionable, it is at such times that many an Indian youth and maiden fall irretrievably in love, and seek to unite their hands and fortunes in wedlock. When this is understood, and the union receives the approbation of their parents and friends, both are allowed a personal inspection of each other in private; and if this proves satisfactory, the fortunate lover gathers together all his worldly wealth, and repairs with it to his expected future father-in-law. The old man generally appears surprised, hesitates, inspects the candidate for his daughter’s hand from head to foot, then the

|

| INDIAN MARRIAGE CEREMONY. |

Strange as it may seem, the Indian men will not infrequently gamble away their wives, as they do other kinds of property, (for they are inveterate gamblers); and they are far too apt to consider the wife but little better than a chattel for barter and sale. Quite often a given number of Indian men agree to fight for a certain number of Indian women, on which occasion each party puts up equally. As soon as either side is victorious, the women, who have been awaiting this “hazard of the die” as interested spectators, arise, and without hesitancy, or question, accompany the victors; and are apparently contented with the result. To obtain women was frequently the only cause for war among them. And when any particular tribe ran short of squaws, it unceremoniously stole some from an adjoining tribe; which, on the very earliest favorable occasion, returned the doubtful compliment, and sometimes with considerable interest. Polygamy is quite common, some of the chiefs having from three to seven wives, the number being limited only, (as among the Mormons), by their ability to support them.

This profession is very popular among the Indians, and although their knowledge of medical science, even in its rudest and most primitive form, is much more limited than with the tribes east of the Rocky Mountains, they sometimes perform a few simple cures, and on this account are looked up to with consider able respect. The Indians have got great confidence in their “medicine men,” and believe them endowed with the power of insuring health, or of causing sickness, or even death; but if they think that the doctors have used this power arbitrarily, or unworthily, they are unceremoniously put to death. Their methods for relieving pain and curing disease are as unique as they would be amusing to a skillful practitioner. They have, however, learned a little of the sophistry and finesse of the profession, and use it with considerable skill. As illustrative of this, as they generally scarify, to suck away all pain, they will sometimes put small stones, or bits of stick, or wild coffee berries, into their mouth, and produce these to the patient to induce him to believe that this or that has been the cause of all his pain; and as he has been successful in removing the cause, the pain will naturally cease!

They all believe in a good spirit, and also in a very evil spirit. The good spirit, according to their apprehension, is always good; and, therefore, ever to be loved and trusted, without fear or dread; that, consequently, there is no use in giving them selves any trouble about him. But not so with the evil spirit, as in his nature are concentrated all the bad qualities of twenty Pohono’s condensed into one; and, therefore, he is the one that needs watching, and conciliating if possible.

They also believe in a pleasant camping ground after death, one that is most bountifully supplied with every comfort, and where they will again meet all their relatives and friends, and live with them in ease and plenty forever. This camping ground is presided over by the good spirit, a semi-deity or chief of great power and kindness, and who is ever making them supremely happy. They also believe that the evil spirit is doing everything that he can to make them miserable, and keep them away from this happy camping ground; that, therefore, their principal religious duties consist in avoiding, circumventing, or placating him.

They believe that the heart is the immortal part, and that if the body is buried the evil one stands perpetual guard over the grave, and will eventually secure the heart as his wished-for prisoner and prize. With the view of defeating this wicked purpose, they invariably burned the bodies of their dead (a practice that has been largely discontinued in later years, and the example of the whites followed, in burying them), thinking by noises and grotesque motions, accompanied by expressions of poignant sorrow, to attract the attention of the evil one while the body is burning, and thus give the heart the opportunity of slipping away unobserved. Hence their custom of cremation.

When an Indian is known to be near his departure to the spirit land—as they are all in a certain sense more or less spiritualists—his head is generally pillowed in the lap of his wife, or dearest friend; when, all standing around commence a low, mournful chant upon the virtues of the dying; and with this soothing lullaby falling upon his ears, he passes to the deep sleep of death. As soon as his heart has ceased to beat, the sad news is carried by runners to all his relatives, both far and near; and the low chant is changed to loud and frantic wailings; accompanied by violent beatings of the chest with their clenched fists; while with tearful eyes directed upwards, they apostrophize the spirit of the departed one in their own behalf.

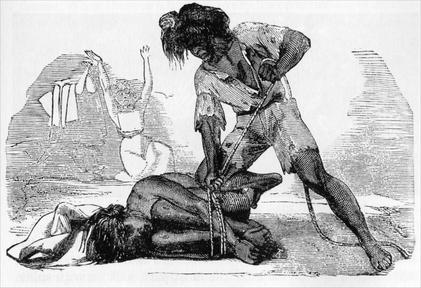

It is a singular fact that although some Indians now bury their dead, and others burn them, in either case the same preparations are made for final disposition, which are as follows: A blanket is spread upon the ground, and the corpse laid thereon,

|

| PREPARING THE BODY FOR CREMATION. |

When the fuel, composed mainly of pitch pine and oak, is about two feet high, every sound again ceases; and, amid a death like stillness, the men place the body upon the pyre. This accomplished, additional wood is piled upon and around it, until all except the face is completely covered up. Then, slowly and solemnly, the nearest and oldest relative advances, with torch in hand, and with deep yet suppressed emotion sets the wood on fire.

|

| INDIANS BURNING THEIR DEAD. |

The moment the first cloud of smoke eddies up into the air, the discordant howling of the women becomes deafening, and almost appalling; while the men, for the most part, look on with sullen and unbroken silence.

Those who are nearest and dearest to the fire-consuming dead, with long sticks in their hands, dance frantically around; and occasionally stir up the fire, or turn the burning body over, to insure its more speedy consumption by the devouring element; hoping by these united movements to attract the evil one’s attention, and give the heart the opportunity of eluding his watchful glances, and of escaping unseen to the happy camping ground.

After the body is nearly consumed, the blackened remains are taken from the fire, rolled up in one of their best blankets, or cloths, and allowed to cool a little; when his wives, or those nearest and dearest, segregate the unconsumed portions, and wrap every piece separately in strings of beads, or other ornaments; they then place them carefully in a basket that has been most beautifully worked for the occasion, with any other valuables possessed by the departed one; and the fire being rebuilt, the basket and its contents are placed upon it; with blankets, cloths, dresses, bows and arrows, and every other article that has been touched by the deceased, and all are then committed to the flames. When these are burned, every unconsumed log is carefully scraped, the ashes swept together, and the whole, with the exception of the portion always reserved for mourning, are then placed in another basket and carefully buried. All Indians, with out exception, cast the personal property of the deceased, as well as presents of their own, into the grave; so that he may want nothing when he enters the camping ground, believed to be some where in the far distant West. The reserved ashes being mixed with pitch is spread over the faces of the female relatives as a badge of mourning; and which, although hideous to our sight, is sacred to theirs; and is allowed to remain until it wears off, which is generally about six months. Sometimes the old squaws renew their mourning from the cheeks to the ears. A married woman, when her husband dies, invariably cuts off her hair. Mr. Galen Clark, one of the oldest residents of Yo Semite, assured the writer that when in their deepest lamentations for their dead, they cry out, “Him-mah-lay-ah,” “Him-mah-lay-ah,” gesticulating westward.

Next: Chapter 25 • Index • Previous: Chapter 23

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/24.html