| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Vernal & Nevada Falls >

Next: Chapter 26 • Index • Previous: Chapter 24

|

These are thy glorious works, Parent of good.

—Milton’s

Paradise Lost, Bk. V, Line 153.

|

|

The rustle of the leaves in summer’s hush

When wandering breezes touch them, and the sigh That filters through the forest, or the gush That swells and sinks amid the branches high,— ‘Tis all the music of the wind, and we Let fancy float on this Aeolian breath.

—M. G. Brainard’s

Music.

|

|

But on and up, where Nature’s heart

Beats strong amid the hills.

—Richard Milnes.

|

As a rule it is desirable that the trips to Mirror Lake, and to the Vernal and Nevada Falls, should be taken conjointly; inasmuch as the two can be comfortably included on the same day. Besides this when we are at the Tis-sa-ack Bridge, after the Tis-sa-ack Avenue drive, we are two miles on our way to those falls. To avoid doubling the two miles of distance, between Barnard’s and the Tis-sa-ack Bridge, while utilizing the stretch gained, as the remaining two and three-fifths miles to Snow’s Hotel have to be taken on horseback, our saddle animals should meet us at the bridge.

As many persons who visit Yo Semite have never sat on a horse before, and many others have been entirely out of practice of later years, and in consequence are possibly a little nervous about it, it seems to me to be eminently proper that I should here invite their encouraging confidence in themselves, by stating that each horse is well trained, and knows where to set down every foot; so as to insure not only his own safety but that of the precious burden he is bearing. Then, it should be borne in mind that, notwithstanding the many, many thousands who have ridden up and down these mountain trails, there has never been a serious accident upon any one of them, in the thirty-one years this Valley has been opened to the public. Think of this.

Owing to the intersecting connection that has recently been made between the new Anderson trail up the northern bank of the main Merced River, and the Snow trail on the southern bank, at Register Rock, a new, and if possible, more picturesque ride than the former one along the base of Echo Wall, has been opened up. Therefore, instead of crossing to the southern end of Tis-sa-ack Bridge, we will, if you please, take the broad and well-graded Anderson trail at the northern end of the bridge. Maples, dogwoods, oaks, pines, and cedars edge in and arch over our path; and near Cold Spring—the only one on this route—grows a fine clump of tall and feathery Woodwardia ferns. By looking back a few yards beyond this the Valley has the semblance of a forest walled in; while over its distant boundary the Yo Semite Fall is leaping.

Passing just immediately along the foot of Grizzly Peak, where the horse-path has been hewn out of solid granite; or high supporting walls have been built upon it, to make a thoroughfare possible here, it can be readily seen how great were the difficulties to be surmounted.

The late George Anderson, who engineered and constructed it, and after whom it will probably be named, made a contract to complete it to Snow’s Hotel for $1,500. This, however, was all expended before Grizzly Peak was passed. A similar amount was voted him for finishing it, but this was also found to be far from sufficient; he was then engaged to continue it, ad libitum; but, after some $5,000 had been expended upon it, and the granite wall along the north side of the Vernal Fall, over which the trail was to run for over eleven hundred feet, had scarcely been touched, further work upon it was for the present suspended. This broad and substantial trail, however, remains a monumental acknowledgment of Anderson’s skill, pluck, indomitable will, and undiscourageable perseverance.

The trail (almost wide enough for a wagon road), presents sublimely delightful pictures of the rushing, boiling, surging river; and the finest of all views, of the Too-lool-a-we-ack, or Glacier Cañon, stretching the entire length of it to its four hundred feet water-fall, near the Horseshoe Grotto at its head. This cañon is called by Prof. J. D. Whitney the “Illilouette,” a supposed Indian name; but I have never questioned a single Indian that knew anything whatever of such a word; while every one, without an exception, knows this cañon either by Too-lool-a-we-ack or Too-lool-we-ack; the meaning of which, as nearly as their ideas can be comprehended and interpreted, is the place beyond which was the great rendezvous of the Yo Semite Indians for hunting deer. However this may have been, the way up to it was certainly never through this cañon, if it always had surroundings as wildly impassable as the present ones.

Before crossing the Merced River, those who are good walkers and delight in grand scenes, should leave their horses at the junction of the trails, and make their way afoot to the top of the debris at the back of Anderson’s old black Smith shop; as thence magnificent views are obtained of both the Vernal and Nevada Falls, with all their varied mountainous surroundings. Before very long a good horse-path will probably be made to this point; and, possibly, to the foot of the Vernal Fall, on the north side of the river.

Those who have ever witnessed the glorious scene this fall presents from the Lady Franklin Rock, some two hundred yards above, can form an approximating idea of its impressive majesty from this fine standpoint. Dr. Wm. B. May, Secretary to the Board of Commissioners, thus reports this scene to the Board: “Standing upon the new bridge, with the Vernal Fall in the near upper view, and the wealth and war of rushing waters beneath one’s feet, there is a presence of power and grandeur, hardly equaled in the Valley.” The musical Merced, as it roars, and gurglingly rushes among and over huge bow1ders, that here throng the channel of the river, possibly calls to memory that passage of holy writ: “And I heard as it were the voice of a great multitude, and as the voice of many waters, and as the voice of mighty thunderings, saying, Alleluia; for the Lord God omnipotent reigneth.”

This is an immense, overhanging, smooth-faced “chip” of rock about the size of an ordinary village church; upon which very many have, at various times and seasons, inscribed their names; not so much for expected immortality, perhaps, as to inform their friends, who may at some subsequent season see it, that they have been here. There is one entry upon a sloping side rock, that is perhaps worthy of notice, as it reads, “Camped here August 21, 1863. A. Bierstadt, Virgil Williams, E. W. Perry, Fitzhugh Ludlow.” It was during this visit to the Valley that Mr. Bierstadt made the sketch from which his famous picture, “The Domes of the Yo Semite,” was afterwards painted.

This name was given in honor of the devoted wife of the great Arctic voyager, Sir John Franklin, who paid Yo Semite a visit in 1863. From this rock one of the best of all views is obtained of

The Indian name of this magnificent water-leap is “Pi-wy-ack,” which, if it could be literally interpreted, would express a constant shower of scintillating crystals. Seen from below, it is an apparently vertical sheet of water, of sparkling brightness, and of almost snowy whiteness, leaping into a rock-strewn basin at its foot; whence vast billows of finely comminuted spray roll forth in surging waves, and out of which the most beautiful of rainbows are built, to span the angry chasm with a befitting halo of exalting glory. This fall, if possible, impresses one more than any other with the feeling of Infinite Power.

[Editor’s note: The correct Ahwahneechee name for Vernal Fall is Yan-o-pah. Pi-wy-ack refers to Tenaya Lake and was mistakenly transfered as the name for Vernal Fall. Bunnell, Discovery of the Yosemite (1880), p. 207. —dea]

Its vertical height, by nearly every measurement, is three hundred and fifty feet; and its breadth on top, varying of course somewhat with the differing stages of water, is about eighty feet. The Wheeler U. S. Survey corps made the altitude of this fall three hundred and forty-three feet. Professor Whitney, State Geologist, thus speaks of it:—

The first fall reached in ascending the cañon is the Vernal, a perpendicular sheet of water with a descent varying greatly with the season. Our measurements give all the way from 315 feet to 475 feet for the vertical height of the fall, between the months of June and October. The reason of these discrepancies seems to lie in the fact that the rock near the bottom is steeply inclined, so that a precise definition of the place where the perpendicular part ceases is very difficult amid the blinding spray and foam. As the body of water increases, the force of the fall is greater, and of course it is thrown farthest forward when the mass of water is greatest. Probably it is near the truth to call the height of the fall, at the average stage of the water in June or July, 400 feet. The rock behind this fall is a perfectly square-cut mass of granite, extending across the cañon, etc.

Now, inasmuch as, according to Professor Whitney’s admission, it is a “perpendicular sheet of water,” and “the rock behind this fall is a perfectly square-cut mass of granite extending across the cañon,” I must confess my inability to see that there could, by any possibility, be a difference, at any time, of more than a foot or two at most; as, when the water was highest on the top, the same result would be noticeable in the pool at the bottom; thus precluding the probability of a difference of one hundred and sixty feet in a “perpendicular” fall of three hundred and fifty feet. Had the steep inclination spoken of been applied to the Nevada Fall wall, it would have been perfectly correct, but it is not in the least degree when speaking of the Vernal.

Many attempt this when the fall is fullest; but, novel as the experience may be, the proceeding, in my judgment, is not among the wisest to the average visitor. Over two hundred feet of altitude has to be attained through blinding spray; which not only closes the eyes, but takes away the breath needed for the climb. It is far better to come down through this, and have it helpfully at our backs, than defiantly and drenchingly in our faces. But, should it be attempted, one is soon enveloped in a heavy sheet of spray, that is driven down in such gusty force as to resemble a heavy beating storm of comminuted rain. It is true that to an athletic climber, with good lungs, it is not only possible, but enjoyable; and, moreover, is very soon accomplished. Ladies, however, attempting this will need suitably short dresses; or they will not only be inconvenienced at every step, but incur the danger of falling; and, possibly, of rolling down into the angry current below.

Prudence, therefore, suggesting that this should be deferred until our return, let us retrace our steps to the horses at Register Rock; that, by this time, are sufficiently rested to carry us safely up the zigzagging trail to the top of the hill, some eight hundred feet above us. At almost every turning in the trail its sinuosities enable us to look upon the members of our party, and exchange with them a greeting look, a kindly word, or snatches of a favorite song. Our progress upward is necessarily slow, as the animals need to pause for breath, if not for strength; but trees and tree shadows, mossy rocks, and towering cliffs bespeak admiring thoughts for every moment. When about two-thirds of the climb has been overcome, from a corner of the trail, looking back, the top of Yo Semite Fall comes into view. But presently we find ourselves crossing the highest point on the way to Snow’s, and before us opens a scene never to be forgotten. It is the Cap of Liberty, and Nevada Fall.

|

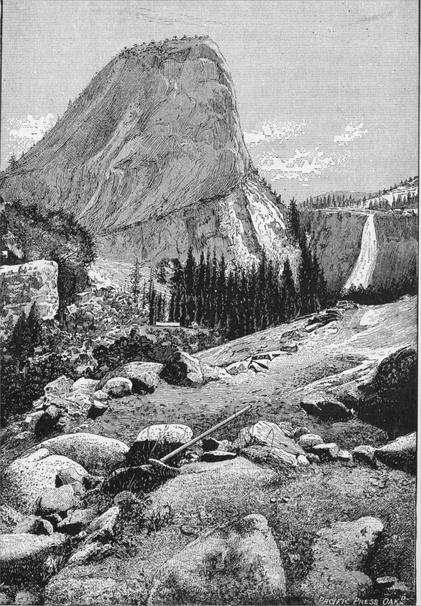

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. |

| CAP OF LIBERTY AND NEVADA FALL. |

Of these two there seems to be a difficulty in determining which is the most attractive; but, taken together as here presented, the scenic combination is marvelously imposing. Let us, however, separate them, momentarily, for consideration, notwithstanding “they are but parts of one stupendous whole.”

Owing to the exalted and striking individuality of this boldly singular mountain (some most excellent judges pronouncing it only secondary to El Capitan), it had many godfathers in early days; who christened it Mt. Frances, Gwin’s Peak, Bellows’ Butte, Mt. Broderick, and others; but, when Governor Stanford (now U. S. Senator) was in front of it with his party in 1865, and inquired its name, the above list of appellatives was enumerated, and the Governor invited to take his choice of candidates. A puzzled smile lighted up his face and played about his eyes, as he responded, “Mr. H., I cannot say that I like either of those names very much for that magnificent mountain; don’t you think a more appropriate one could be given?” Producing an old-fashioned half dollar with the ideal Cap of Liberty well defined upon it, the writer suggested the close resemblance in form of the mountain before us with the embossed cap on the coin; when the governor exclaimed, “Why! Mr. H., that would make a most excellent and appropriate name for that mountain. Let us so call it.” Thenceforward it was so called; and as every one preferentially respects this name, all others have been quietly renunciated.

Its altitude above Snow’s Hotel, by my aneroid barometer, is one thousand eight hundred feet. The singularity of its form and majesty of presence must impress every beholder. For many years it was pronounced inaccessible, but a few enthusiastic spirits found their way to the top. Apparently such an isolated mass of granite could scarcely find foot-hold for a few bushes, that strugglingly eked out a half-starved existence; but, strange as it may seem, when once upon its crown, quite a number of goodly sized trees and shrubs are found; among which are nine juniper trees, Juniperus Occidentalis two of which are over ten feet in diameter, and must be some fifteen hundred years old. The moss on these is the most beautiful when in blossom, of any that I ever saw. There are also several Douglas spruce trees, Psudotsuga Douglasii; and the dwarf shrub oak, Quercus dumosa, manzanita, and others; besides flowers, flowering shrubs, and ferns.

But a view from the top of the Cap of Liberty repays for all the fatigue attending the scrambling climb to reach it. Deep down in the Little Yo Semite Valley (the entire length of which is visible), meanders the Merced River. Tall pines and firs, everywhere abundant, appear like toy trees about the right size for walking-canes. But, let us take courage, and walk out to the edge of the Cap; as, at the southeastern corner, there is a large glacier-left bowlder which offers clinging support for our fingers, while steadying our nerves, so that we can look down into the abyss between us and the Nevada Fall; noting the form and graceful sweep of its waters and the dazzling whiteness of its sheeny foam. Echo Wall, Glacier Point, Sentinel Dome, the top of El Capitan, Eagle Peak, Yo Semite Fall, Grizzly Peak, omnipresent Half Dome, Cloud’s Rest, and Mount Starr King, with numerous points and ridges, are all in full sight.

Returning, in thought, to the point whence our first glimpse of these wonders was obtained, we follow the sinuosities of the trail nearly to the blink of the chasm, into which we can see the Vernal Fall leaping. When nearest, it would be well here to dismount; and, carefully picking our way down within a few feet of the edge (where a safe and convenient opening between blocks of rock enables us to sit comfortably), by leaning over a little, we can watch the water-fall leaping from its verge on the top to the pool at the bottom. This charming view is too often passed by without being noticed and enjoyed.

Before bestowing more than a passing glance on the multitudinous objects of uncommon interest in this vicinity, if they are to be enjoyed, thoroughly and in detail, it would be well to repair directly to Snow’s, for rest and refreshment.

This hospice is situated about midway between the top of the Vernal, and foot of the Nevada Falls.’ It has become deservedly famous all over the world, not only for its excellent lunches and general good cheer, but from the quiet, unassuming attentions of mine host, and the piquant pleasantries of Mrs. Snow. I do not think that another pair, anywhere, could be found that would more fittingly fill this position. And, although they do not know whether the number to lunch will be five or fifty-five, they almost always seem to have an abundance of everything relishable. On one occasion—and this will illustrate Mrs. Snow’s natural readiness with an answer—a lady, seeing so great a variety upon the table, with eager interest inquired, “Why! Mrs. Snow, where on earth do you get all these things?” “Oh! we raise them!” “Why! where can you possibly do so, as I see nothing but rocks around here?” “Oh! madam, we raise them—on the backs of mules!”

From the porches of the Casa Nevada, and its comfortable “cottage,” the glorious Nevada Fall, where the whole Merced River makes a leap of over six hundred feet, a magnificent view is obtained. The roar of this fall, and the billowy mists that in early spring roll out such eddying and gusty masses of spray, arched by rainbows on every sun-lighted afternoon, will cap tivate and charm our every emotion. The best view, probably, of this sublime spectacle is from the foot-bridge, over the hurrying and wave-surging river. There a scene is presented that fills the soul to overflowing with reverential and impressive awe; as, with uncovered head, the self-prompted mental question is in silence asked, “Is not this the very footstool of his throne?”

“The Nevada Fall is,” says Prof. J. D. Whitney, “in every respect, one of the grandest water-falls in the world; whether we consider its vertical height, the purity and volume of the river which forms it, or the stupendous scenery by which it is environed.” This is an opinion that I have frequently heard expressed by travelers from many lands. When in front of it, and looking upward, it can readily be seen that this fall differs in form with either of the others; for, although it shoots over the precipice in a curve, it soon strikes the smooth surface of the mountain, and spreads out into a sheet of marvelously snowy whiteness, and of burnished brightness, widening as it descends, until it sometimes exceeds one hundred feet in breadth, at the pool into which it is leaping. The height of this fall is given at six hundred and five feet by the Wheeler U. S. Survey corps.

This point being as near as visitors generally go—although many enthusiastic climbers and appreciative lovers of the beautiful seek the wonderful view from its top—we will, for the present, if you please, ask the guide to take our horses down to Register Rock, while we say good-by to our genial host and his wife, and then seek the wondrous scenes below, afoot.

A gentleman who, from modesty, desires that his name may be kept a secret, once took an unfair advantage of a confiding visitor, by informing him that there were nearly eleven feet of snow visible here throughout the hottest days of summer. “Is it possible? Oh! how much I should like to see it.” “Please allow me, then, to introduce you to Mr. and Mrs. Snow—the former being five feet nine inches, and the latter making up the remainder!”

Soon after leaving “Snow’s,” we find ourselves upon the bridge that here spans the river. Listening to the roar of the fall above, we naturally turn our faces towards it, and then look down into the apparently insignificant stream beneath us, and think, can this be the whole of the main Merced River? It scarcely seems possible, but so it is. Its narrow, rock-bound, and deep, trough-like channel confines it to a width seldom exceeding ten feet. While it is swashing and rushing on, let us turn our gaze to the opposite side, and look down on

We now readily appreciate the apposite character of its name; for, down, down, the whole river is leaping, as if in very wantonness and exultation at the liberty it has gained; and, being seized with an uncontrollable fit of frolicking, is tossing up diamonds (of the purest water) with a prodigality and apparent improvidence that would shock the sensitive acquisitiveness of “My Uncle,” if he could see it. By the demureness of its demeanor, however, below, as it “pursues the even tenor of its way,” it would seem to be laughing in its sleeve, and saying, “You see, I was only in fun—don’t mind me!” Around a jutting point of rock, we find ourselves at the Silver Apron.

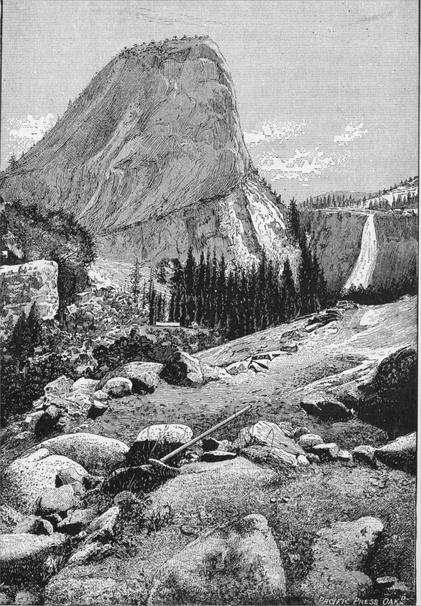

|

| SILVER APRON, AND DIAMOND CASCADE, FROM BELOW. |

When standing near the edge of the impetuous current, and looking up towards the Diamond Cascade Bridge we have so recently crossed, the whole river seems to be attempting, in the most reckless manner, to throw its separated and scintillating drops and masses into our faces; but, unmindful of, or excusing this, we cannot resist the temptation of watching the sportive and sprightly fearlessness of its dashing abandon; or the astonishingly brilliant beauty of this sparkling outlet from the Diamond Cascade.

Directly in front of us, and down at our left, the whole river is scurrying over smooth, bare granite, at the rate of a fast express train on the best of railroads. Pieces of wood or bark tossed upon its silvery bosom tell instantly of its marvelous speed.

An English gentleman who was making his temporary residence at Snow’s Hotel, amazed its inmates one morning by appearing on the scene with his face badly cut, and his hands bleeding. With astonished surprise at such a sight Mr. Snow innocently inquired:—

“What on earth, man, have you been doing to yourself, to get into such a plight as that?”

Looking steadfastly at the questioner, while wiping the red stains away with as much easy deliberation as though a little dust had fallen upon his face, and needed removal, he hesitatingl-y made answer:—

“Th-the-there is, you k-know, a s-smooth k-kind of place in the-the river, j-just b-be-low the-the lit-tle bridge, you know, w-where the-the wa-water p-passes s-somewhat r-rapidly over the-the-rock, you know.”

“Oh! yes,” replied Mr. Snow, “I remember; that is what we call the ‘Silver Apron.’ Well?”

“W-well, w-when I g-gazed up-upon it, I-I-th-thought it-it w-would be a-a-de-lightful p-place to t-t-take a-a b-bawth, you k-know.”

“Why, sir,” responded the landlord of the ‘Casa Nevada,’ aghast, and interruptingly, “why, the whole Merced River shoots over there, at the rate of about sixty miles an hour—faster than a locomotive goes upon a railroad!”

“Is-is i-it p-possible? W-we-well, I h-had n-no s-sooner d-disrobed m-my-s-self, and s-set m-my Hoot in-into th-the h-hurrying c-c-current, y-you k-know, t-than i-it k-knocked m-me off m-my p-ins, you know! an-and s-swept me d-down s-so s-swiftly th-that it q-quite t-took my b-breath a-away f-for a f-few m-moments, you k-know; s-sometimes i-it r-rolled me o-over and o-over, a-and a-at o-other t-times s-shot me d-down en-endwise, y-you k-know; a-and fi-finally b-brought m-me up-in a s-sort of pool, y-you know!”

“The Emerald Pool,” suggested Mr. Snow.

“And, b-by G-George, if I h-had no-not b-been an ex-excellent swim-swimmer, I s-should cer-certainly h-have I-lost my life, you know! A-and, it is n-not my h-hands a-and m-my f-face o-only-i-it is a-all o-over m-me-like that, you know!”

Opinions are sometimes hastily formed, and are not always supported by the best of good reasons; and it may be so in this case, but the supposition most generally prevails, that, when this gentleman wishes to take another “bawth,” he will not seek to do so at the “Silver Apron.”

This is a beautiful lake, or pool, whose waters are, as its name signifies, “emerald.” The river’s current, driving with great force into its upper margin, causes a constant succession of waves to disturb its surface, especially during the spring flow. Its mountainous surroundings, trees, and bowIders, add much to the picturesqueness of its character. Descending towards

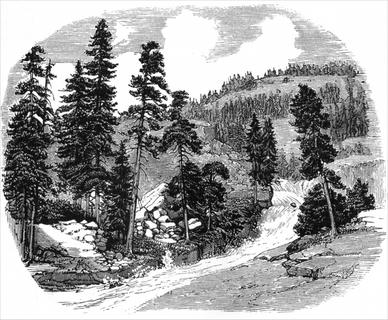

|

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. |

| THE LADDERS—IN WINTER. |

Little patches of glacier-polished rock surface are still distinctly visible, the striations of which indicate the exact course the great ice-field must have once taken. Approaching the edge of the fall, almost before we have glanced at its diamond-fringed lip, we walk up to, and lean upon, a natural balustrade of granite, that seems to have been constructed there for the especial benefit of weak-nerved people; so that the most timid can look over it into the entrancing abyss beneath. After this experience many have sufficient nerve to stand on the edge near the side of the fall, especially if some less nervous person should take them by the hand, and thence looking down the entire front of its diamond-lighted, rocket-formed surface, follow it with the eye to the pool beneath. Sometimes bright rainbows are arching the spray at its foot, and which, extending from bank to bank, completely bridge the billowy mist and angry foam below. But, turning away from these delightful sights, let us seek the “Ladders,” so called from the original, but which have been transformed into substantial steps (to which the old term “ladders” still clings), by which we can descend to Fern Grotto, on our way to the foot of the Vernal Fall Wall.

Here a portion of the mountain has been removed, and left a large cave or grotto, in the interstices of which numerous ferns, the Adiantum pedatum, mainly, one of the maiden hair species, formerly grew in abundance; but constant plucking of the leaves, and removal of the roots, have shorn it of its fern-like character, where they could be reached without danger. A glance at the accompanying engraving will enable the visitor, measurably, to conceive the superb, fairy-like creations of the enchanter’s wand to be found here in winter. Hours might be pleasantly spent at this spot, but we must hurry through the spray to our horses; and while some are returning to the hotel, let us retrace our steps, at least in imagination, as some more enthusiastic natures yearn to see what there is of interest above and beyond this; and which necessarily forms the substance of the ensuing chapter.

Next: Chapter 26 • Index • Previous: Chapter 24

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/25.html