| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Upper Yo Semite >

Next: Chapter 29 • Index • Previous: Chapter 27

|

I love to wander through the woodlands hoary

In the soft light of an autumnal day, When summer gathers up her robes of glory, And like a dream of beauty glides away.

—Sarah Helen Whitman.

|

|

I hear the muffled tramp of years

Come stealing up the slope of Time; They bear a train of smiles and tears, Of burning hopes and dreams sublime.

—James G. Clarke.

|

|

Hills peep o’er hills, and Alps on Alps arise.

—Pope’s

Essay on Criticism.

|

When undertaking the delightful jaunt now proposed, we repair to the north side of the Valley, and enter upon the Eagle Peak Trail. This was engineered and constructed by Mr. John Conway and sons, who performed a very valuable service to the public by opening up very many of the magnificent scenes we are about to witness, and that were before sealed from human vision; but for which, I regret to say, no adequate compensation was returned them.

As we zigzag our way up it by an easy grade, stunted live oaks offer grateful shade, and manzanita and wild lilac bushes border it on either side. Trees, buildings, gardens, cattle, and horses grow gradually more diminutive; while surrounding granite walls tower up bolder and higher. In peaceful repose sleeps the Valley, its carpet of green cut up, perhaps, by pools of shining water, and the serpentine course of the river resembles a huge silver ribbon. At an elevation of 1,154 feet we rest at

And thence look down upon the enchanting panorama that lies before us. Everything visible below has become dwarfed; while in the far-away distance above and beyond us, mountain peaks are constantly revealing themselves impressively, one after the other. Remounting, we ascend a little, then ride along a broad ledge of granite that, from the Valley, appears to be far too narrow for a horse and its rider to travel upon in safety; but, finding ourselves mistaken, we presently arrive at

Here the horses are again left upon the trail, while we foot our way to the edge of the overhanging wall, that, from below looked so formidable a precipice. From this standpoint, not only can the entire length of the lower Yo Semite Fall be seen; but the interjacent depths and irregularities of the intervening cañon between the top of the lower, and foot of the upper fall; while in front of us the entire Upper Yo Semite Fall is in full view. Charmingly attractive as this scene may be, we naturally wish to seek a closer communion with its glories, and cannot rest until we are almost

Speechless with reverential awe, we have reached the wonderful goal. But, alas! who can describe it? who fittingly tell of its wonderful beauties, or describe its manifold glories, and majestic presence? It is impossible. We look upward, and we see an avalanche of water about to bury us up, or sweep us into the abyss beneath. By degrees we take courage; and, climbing the watery mass with our eye, discern its remarkable changes and forms. Now it would seem that numerous bands of fun-loving fairies have set out for a frolic; and, assuming the shape of watery rockets, have entered the fall; and, after making the leap, are now playing “hide-and-seek” with each other among its watery folds; now chasing, now catching; then, with retreating surprises, disappearing from view, and re-forming, or changing, shoot again into sight. While the wind, as if shocked at such playful irreverence, takes hold of the white diamond mass, and lifts it aside like a curtain; when each rocket-formed fairy, leaping down from its folds, first fringes its edge, then disappears from our sight, and is lost among rainbows and clouds.

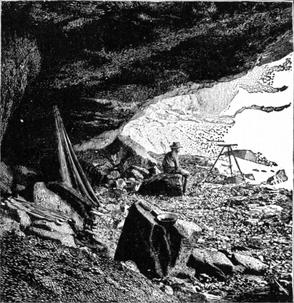

The first great vertical leap of this fall being fifteen hundred feet, makes it scarcely less impressive than El Capitan, when standing against the wall at its foot. Just at the back of, and immediately beneath it, there is a cave some forty feet in depth. As the fall itself veils the entrance to this cave, it can only be entered when the stream is low; or, as not infrequently happens, when the wind has sufficient force to lift the entire fall to one side. On one of these occasions two venturesome young men, who had climbed to the foot of the cliff, seeing the entrance to the cave clear, ran into it; but they had scarcely entered when

|

| Photo by C. E. Watkins. |

| CAVE AT THE BASE OF THE UPPER YO SEMITE FALL. |

Leaving this interesting and truly captivating spot, we continue our crinkled way up the debris lying at the base of Eagle Tower wall (vertical for 1,600 feet), passing flowers and flowering shrubs, to enter into the refreshing shade of a grove of yellow pines, Pinus Jeffreyi, and soon thereafter find ourselves at the

The current of this stream is very irregular. For nearly half a mile it has a speed of about eight knots an hour; then, for about two hundred yards from the lip of the mountain, it leaps over a broken series of ledges into eddying pools, from which it swirls and swashes, and jumps, until it makes its final bound over the precipice, and is lost to view. For about ten yards back of the edge, the gray granite is so smooth that, lying down upon it, clingingly, when the stream is absent, it would be impossible to prevent sliding over the brink, but for a narrow crack in the rock where there is finger-hold. This enables us to cling sufficiently, until we can work our way out to a flattish, basin-like hollow, in safety; whence one can creep out to the margin of the abyss, and look down into it. My measurement here, by aneroid barometer, made its height above the Valley two thousand six hundred and forty feet. Its breadth at the lip is thirty-four feet; and, twenty feet above it, seventy feet. One position on a projecting ledge enables the eye to follow this water-fall from top to base, and watch the ever-changing colors of its rainbow hues the entire distance.

From this point it is a most delightful forest ride to Eagle Meadows, their grassy glades, and pools covered with bright yellow water-lilies, Nuphar polysepalum, and thence to

This was so named from its being such a favorite resort of this famous bird of prey. I once saw seven eagles here, at play; they would skim out upon the air, one following the other, and then swoop perpendicularly down for a thousand or more feet, and thence sail out again horizontally upon the air with such graceful nonchalance that one almost envied them their apparent gratification.

The altitude of this rugged cliff above the Valley is three thousand eight hundred and eighteen feet, three hundred and thirty feet lower than the Sentinel Dome on the other side; but, owing to the great vertical depth of the gulf immediately beneath it, as well as the comprehensive panorama from and around about it, not only is the entire upper end of the Valley, with its wild depths and cañon defiles, visible therefrom, but the whole sweep of the distant Sierras, as far as the eye can reach.

I once had the pleasure of conducting the Rev. J. P. Newman, D. D., and Rev. —— Sunderland, D. D. (each, then, of Washington, D. C.), to its wondrous summit; when, after a long, and evidently constrained silence, the former suddenly ejaculated, “Glory! Hal-le-lu-jah—Glory! Hal-le-lu-jah!” (the doctor was a Methodist, you know) then, turning around, the tears literally streaming down his cheeks, he thus expressed himself. “Well, Mr. H, if I had crossed the continent of America on purpose to look upon this one view, I should have returned home, sir, perfectly satisfied.”

Eleven of us (six ladies and five gentlemen), after a most delightful camping sojourn of three months in the High Sierra, concluded that to revisit this spot would be a befitting finale to our summer’s pilgrimage. Accordingly some eight additional days were spent upon the grassy meadows below, and in making daily ascents to the culminating crest of Eagle Peak. It is a view that seems never to weary, or to become common-place. Gathering storm-clouds admonishing an early departure we gave reluctant consent; to find, that, within twenty-four hours after breaking up camp, three feet of snow had covered the ground.

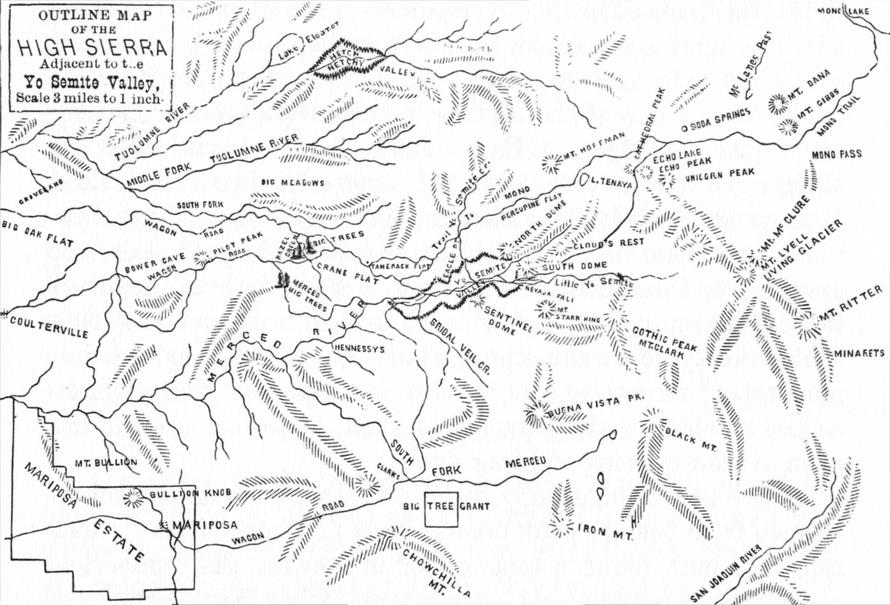

As Eagle Peak Trail is the one necessarily traveled from the great Valley to Lake Ten-ie-ya, and as we have supposedly reached the top of the mountain, and are thus far on our way; let us continue our journey up or down forest-clothed ravines, amid and over low ridges, and across the heads of green meadows, with here and there an occasional glimpse of distant mountain peaks, until we reach Porcupine Flat; thence to travel upon the Great Sierra Mining Company’s Turnpike road all the way to the beautiful lake. It should here be stated that by this thoroughfare travelers can now drive not only among the tops of the Sierras, but over their summit, by leaving the Big Oak Flat road near Crocker’s.

Following the dancing and sparkling waters of Snow Creek, which have their source in the snow-banks of Mt. Hoffmann, there can, on every hand, be witnessed the unmistakable evidences of glacial action, in the moraines, and highly polished and deeply striated granite that can everywhere be seen; not in mere patches only, but many miles in extent. On every peak, mountain shoulder and bare ledge, where disintegration has not removed the writing, the record is so plain that “he who runs may read.” This is most strikingly manifest from the Hoffmann Ridge down to Lake Ten-ie-ya. The entire slope, some three miles long, is glacier-polished, and before the road was built the utmost care was needed, in passing down the trail, to prevent horses from falling. The glistening surfaces attract almost as much attention, for the time being, as the scenery.

Refulgent, however, with sheen, the bright bosom of

Can be seen glinting between the trees, and erelong we are treading upon its pine-bordered shores. Oh! how charming the landscape. Mountains from one thousand to two thousand five hundred feet in height bound it on the east and on the south. At the head of the lake they are more or less dome-shaped, glacier rounded, and polished; on the south, Ten-ie-ya Peak towers boldly up, and throws distinctly and repeatedly back the echoes of our voice. But for persuasive remonstrances from our organs of digestion, we could almost believe that we were in Fairy Land. These humanizing appeals, however, are not to be repressed, and, as a sequence, we find ourselves crossing the hospitable threshold of

The name of its builder and proprietor being John L. Murphy, let me without ceremony introduce him. Mr. Murphy is one of the old-time residents, and was, formerly, one of the most obliging and reliable of the guides of Yo Semite. If you will read H. H.’s “Bits of Travel,” you will find a correctly drawn and full length pen-portrait of him. Wiry with exercise, grizzled by exposure, and healthy from breathing pure mountain air, he is a little Hercules in strength and endurance. Then there are but few, if any, more kindly-hearted, genial, and thoughtfully careful of your comfort than he. Be sure of one thing, the moment you feel the grip of his manly hand, and have one look into his honest face, you will feel thoroughly at home with him; in entire confidence, therefore, we may share his kindly care.

This charming mountain-locked lake is about one and three quarters miles in length by three-quarters of a mile in width; and although very deep on its southern side is quite shallow on its northern, so that before the new road was built, the course of the trail eastward was, for half a mile, directly through it, to avoid the mountainous defile north of its encompassing bluffs.

There is a most curious phenomenon observable here, nearly every still morning during summer, that deservedly attracts attention. It is a peculiar sound, something between a whistle and a hiss, that shoots through the air with startling velocity, apparently about a mile above the surface of the water. Its course is generally from south and west to north and east; although it seemingly travels, at times, in all conceivable directions, and with a velocity much greater than a screeching shell in battle. Now the question arises, “What is the cause of all this?” Can it be from the rapid passage of currents of electricity through the air, or the rush of air through some upper stratum? Will someone who knows kindly answer the question, “What is it?”

The mountains around the lake—Ten-ie-ya Peak, Ten-ie-ya Dome, and Murphy’s Dome, standing out most prominently—are very irregular in their form and cleavage, but yet are unspeak able picturesque. This, with the quaint ruggedness of the Pinus contorta trees which grow upon its margin; the glacier polish and striae upon nearly all of its surrounding granite; the balmy healthiness of its summer air (as meat never spoils, on the hottest of days), its altitude above sea level being seven thousand nine hundred and seventy feet, the purity of its waters, and its central position for climbing every grand peak around it, should make Lake Ten-ie-ya one of the most delightful summer resorts in the world; especially when its waters are well stocked with fish, and the sheep-herder no longer pastures his sheep near, which drive away all the game that would naturally seek these great solitudes. Attractive as this wildly romantic spot may be, we must leave it and its genial hermit, for a time at least, to visit, in spirit, some of

From Yo Semite to the summit of the Sierra Nevada there abounds more grand scenery than can be found in any other portion of the State.

—Prof. W. H. Brewer.

|

The marvelous scenic and natural phenomena of the High Sierra was as a closed volume to nearly all except the irrepressible prospector and vandalistic sheep-herder, until its wondrous pages were opened to the public by the California State Geological Survey, under Prof. J. D. Whitney. Although nature here builds her prodigious reserves of snow, storms hold unchecked carnival, and the chemistry of trituration is silently manipulating its manifold forces, and eliminating scenes of grandeur that charm both eye and soul, human eyes and thoughts could not before look in upon her astonishing laboratory. Now, however, the glorious book is wide open, and its inviting leaves can be turned by every mind. Being a vast and interesting volume of itself, I can now only epitomize and outline some of its principal attractions, that are as wild and wonderful in their way as the Yo Semite itself, while being utterly unlike it. The one nearest, and whose bold prominence we have noticed from all the high points more immediately around the Valley, is

The summit of this mountain is ten thousand eight hundred and seventy-two feet above sea level, and the view from it commandingly fine. Just beneath its northern wall is the horseshoe-shaped head of Yo Semite Creek, with its numerous little glacier-scooped lakelets; and which, with deep snow banks, form the main source of Yo Semite Creek. Here that stream heads. About one hundred feet from its apex is

Where stunted pines, Pinus albicaulis, form the only and highest occupant. Owing to the density of foliage and singular contour of these trees, caused mainly by exposure of situation and the depth of winter snows. one could, with care, walk on their tops, seldom over a dozen feet above the ground. As intimated elsewhere, the upper timber line of the Sierras in this latitude never exceeds eleven thousand feet; at Fishermen’s Peak (unfairly called Mt. Whitney) it is twelve thousand two hundred and twenty, while at Mt. Shasta, it is only eight thousand feet. Beyond and above these the whole chain consists of bleak and storm-beaten peaks and crags; yet, though forest verdure is denied them, beautiful flowers bloom in sheltered hollows, to their very summits. How thoughtlessly do we sometimes allude to “the bleak and desolate mountains,” forgetting that in these are treasured the subtle essences needed for the pabulum of plant, and other organic life, even to their coloring and fragrance.

Were we to lingeringly dwell on these, or upon the echoes thrown from peak to peak upon this crest, where “Every mountain now hath found a tongue,” or in viewing the numberless rocky pinnacles and placid lakes in sight, I fear that other scenes and charms would remain unenjoyed; therefore, let us return to Lake Ten-ie-ya, with the impression that another glorious and soul-filling day has been most profitably spent.

Rafting on the lake, musing, sketching, day-dreaming, nor even pleasant chats with the kind old Hermit of Lake Ten-ie-ya, must detain us from taking the picturesque road along the mar gin of this captivating sheet of water; and, threading our way by the side of bold bluffs, along the tree-arched road, and across a low ridge into the

These afford such striking contrast to other sights witnessed that they somewhat calm the excited imagination by their sylvan peacefulness, and by gratified change prepare us for the sublime scenes that everywhere stand guard. Of course, we must visit

There are several of these that flow bubblingly up in close proximity to each other, and offer us a deliciously refreshing drink of aerated soda water. Here, too, we may meet a hermit-artist named Lembert, who annually brings his Angora goats to feed upon the succulent pastures, whilst he makes sketches. Here we are eight thousand five hundred and fifty-eight feet above the sea. Leaving these we pass glacier-polished bluffs, cross entire ridges and valley stretches of moraine talus, and in about nine spirit-delighting miles, reach the camping ground of Mount Dana. Knowing that blankets and other creature comforts are essential for these extended trips, such things have naturally been provided, preparatory to spending a pleasant night here before attempting

Our course to the summit of this lofty standpoint, after leaving camp, is on the back of an old moraine for some three miles, where Dana Cañon is entered. Here we leave the last tree behind and below us, and thenceforward find nothing but stunted willow bushes, which also are soon left behind, and at an elevation of eleven thousand seven hundred and fifty feet, we are on the saddle, or connecting neck, between Mt. Gibbs and Mt. Dana. Just over the ridge is a large bowlder which, when a rope is tied around it, makes a fast and sheltered point for tethering horses. The ascent thence is on foot, over fragmentary chips and blocks of metamorphic slate, of which this entire mountain is composed, in an endless variety of colors and shades. Once upon its glorious apex, we are thousand two hundred and twenty-seven feet above the level of the sea.

The most expressive of language must utterly fail to describe this scene. The vast amphitheater of mountains, cañons, and lakes extending in every direction to the horizon is unutterably sublime and bewildering. North of east, down in a gulf of six thousand seven hundred and seventy-three feet, restfully sleeps Lake Mono, which, although eighteen by twenty-three miles across, is dwarfed into comparative insignificance; beyond this lie the vast deserts and green oases of the State of Nevada, with their in exhaustible mineral wealth. Trending northward, the irregular mountain-formed vertebrae of the great backbone of the Sierras, with Mts. Warren, Conness, and Castle Peak’ stand up above yet among thousands of lesser ones; while southward, in stately prominence, soar Mts. Lyell, Ritter, and numberless others. Westward the penumbra of light and shade defines every lofty crag and peak that surrounds the wonderful Valley, with every bristling intermediate spire, and cone, and dome.

Along the western and southern slopes of Mt. Dana [says Prof. J. D. Whitney*] [* Yosemite Guide Book, page 103.] the traces of ancient glaciers are very distinct, up to a height of 12,000 feet. In the gap directly south of the summit a mass of ice must once have existed, having a thickness of at least 800 feet at as high an elevation as 10,500 feet. From all the gaps and valleys of the west side of the range, tributary glaciers came down, and all united in one grand mass lower in the valley, where the medial moraines which accumulated be tween them are perfectly distinguishable, and in places as regularly formed as any to be seen in the Alps at the present day.

It is, therefore, reasonably presumable that glaciers once covered the apex of Mt. Dana also, then probably much higher, to a depth “of at least eight hundred feet,” which would give an aggregate approximate depth or thickness of glacial ice in Yo Semite Valley of nearly two miles!

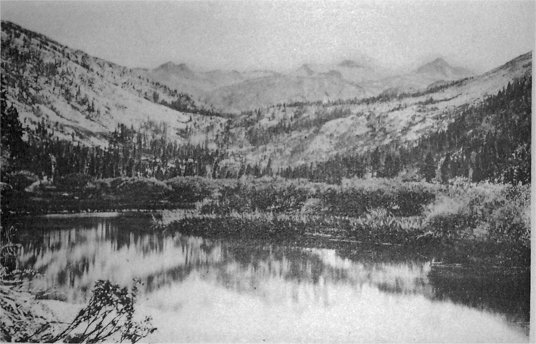

| |

| Photo by S. C. Walker. | Photo-typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| Mount Lyell and Its Living Glacier, from Tuolumne Meadows. | |

| (See pages 487-88.) | |

In the deep vertical chasm under the northern wall of Mt. Dana and near its crest, there is a vast deposit of ice that remains unmelted through all seasons of the year. Unlike that on Mt. Lyell, however, it is completely locked in by an encompassing mountain that precludes the possibility of motion, except normally, as the ice melts. This forms one of the main sources of the Tuolumne River. On the very summit of this bleak landmark grow bunches of bright purple flowers, the Jacob’s Ladder of the High Sierra, Polemonium confertum.

Leaving these enrapturing scenes and mysteries, let us wend our delighting way, over old moraines, and past the glacier polished floor of the Lyell branch of the Tuolumne meadows, to their head, where there is an excellent camping ground, whence the hoary head of Mt. Lyell itself looms grandly up, six miles away. Here we are at an altitude of eight thousand nine hundred and fifty feet. Forest fires set by sheep-herders having denuded much of the lower portion of the ascent of its timber, we must not expect the refreshing shade formerly enjoyed from it. At this altitude, however, the heat is in no way oppressive, although we have on foot to make

Believe me, this is a glorious climb. The invigorating air seems to permeate every fiber and nerve, and to penetrate almost to the marrow of one’s bones. Flowers, flowering shrubs, and ferns, with occasional groups of trees, continue with us to the limit of the timber line, and the former to the very summit, which is thirteen thousand two hundred and twenty feet above sea level.

About fifteen hundred feet below its culminating crest we reach the foot of the glacier, portions of which having broken off and fallen into a small deep lakelet, distinctly reveal the ethereal blue of the icy deposit. This fine glacier is about two miles in length, having a direction southeasterly by northwesterly, by half a mile in width, with an estimated depth, or thickness, of from three hundred to five hundred feet. Deep down in the unseen profound of its blue crevasses, water can be heard singing and gurgling, from which emanate the streams that form the source of the main, or Lyell branch, of the Tuolumne River. By several experiments, such as the setting of stakes in line with the general trend of the glacier, it has been ascertained to move at the rate of from seven-eighths to one inch per day. A large portion of its surface is corrugated by a succession of ridges and furrows, from about twenty inches to two feet apart, and the same in depth; having a resemblance to a chopping sea whose waves had been suddenly frozen.

The upper edge of this living glacier is about one hundred and seventy feet below the rocky apex of Mt. Lyell, “which was found to be a sharp and inaccessible pinnacle of granite rising above a field of snow."* [* Yosemite Guide Book, page 104.] Members of the State Geological Survey Corps having considered it impossible to reach the summit of this lofty peak, the writer was astonished to learn from Mr. A. T. Tileston [Editor’s note: John Boies Tileston], of Boston, after his return to the Valley from a jaunt of health and pleasure in the High Sierra, that he had personally proven it to be possible by making the ascent. Incredible as it seemed at the time, three of us found Mr. Tileston’s card upon it some ten days afterwards.

On the southern side of Mt. Lyell there is an almost vertical wall of granite some twelve hundred feet high, rising from a rock-rimmed basin, whose sheltered sides hoard vast banks of snow, which, melting, form the main water supply of the Merced River, flowing through the Yo Semite Valley. Thus Mt. Lyell becomes the source of two valuable streams, the Merced on the south, and the Tuolumne on the north and east.

Of course the view from this magnificent standpoint is exceptionally imposing. Not only are there lofty and isolated single peaks without number, but distinct groups of mountains, that form the sources of as many streams, or their tributaries; with broad lakes and deep cañons on every hand, extending as far as human vision can penetrate, but of which Mt. Lyell seems to be the center. Leveling across to Mt. Ritter (apparently only a stone’s throw from us, although some five miles distant), we judged its altitude to exceed that of Mt. Lyell by about one hundred and thirty feet. The glaciers of Mt. Ritter, and the Minarets, originate and supply the waters of the San Joaquin River. While seated among the blocks of rock that lie on the edge of this glorious crag, a little “chipmunk” ran out from a crevice and began to chatter at us; but we assured him that we were in no way envious of his exalted choice, nor anxious to disturb his prior possessory right or preŽmption claim.

Loose masses of rock, having become detached from its crest, have toppled down upon the glacier; which, in its almost imperceptible declivity, has silently borne them to the edge of the glacier basin, and there dropped them. These form an irregular wall some two hundred feet in height, among which the new-born stream creeps gurglingly, and thence issues forth. These visible glacial “dumps,” as miners would call them, are suggestive of the way that many moraines are first formed.

Treeless slopes, pools, piles of disintegrated rock, broadening streams, and water-worn crevices, with abundant plant life, continue with us from the summit of Mt. Lyell down to the timber line (here some two thousand four hundred feet below), where the Pinus albicaulis becomes the only forest tenant for some distance; soon, however, to be left behind for the companionship of the Pinus contorta, P. Jeffreyii, Abies Pattoniana, and other trees, until we arrive at picturesque “Camp Mt. Lyell;” thence through God’s most glorious picture gallery back via Cathedral Spires and Cathedral Lake, Echo Peak and Echo Lake, Temple Peak, Monastery Peak, Moraine Valley, Sunrise Ridge, Nevada and Vernal Falls, to Yo Semite.

Next: Chapter 29 • Index • Previous: Chapter 27

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/28.html