| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Heart of the Sierras > Seasons >

|

The spring, the summer,

The chilling autumn, angry winter, change Their wonted liveries.

—Shakespear’s

Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act II.

|

|

Everything lives, flourishes, and decays; everything dies, but nothing is lost.

—Good’s

Book of Nature.

|

|

Perhaps it may turn out a song,—

Perhaps turn out a sermon.

—Burns’

Epistle to a Young Friend.

|

Frequently and earnestly has the question been asked,

WHICH IS THE BEST TIME TO GO TO YO SEMITE?

To which I would make answer—not flippantly, or inconsiderately—That which best suits your own personal convenience. The rest should be determined by individual taste and preference. When a warm, early spring first lifts the flood-gates of the snow-built reservoirs above, the water flows abundantly over the falls; but the deciduous trees are leafless, and the earth, unkissed by renewing sunshine for so many months, has put forth no grasses or flowers. Later, when the trees are budding and the blossoms are just peeping, there is a suggestive softness in the new birth developing. Later still the fragrant blossoms fill the air with redolence, and the birds with morning and evening songs. Still later, luscious fruits contribute their inviting treasures to the generous feast; while the deep rich music of the leaping water-falls rolls out its constant peean of joy. And, still later, possibly there is less of the aqueous element, but ethereal haze drapes every crag and cañion, so that each mountain crest apparently penetrates farther and higher into the deep blue of the vast firmament above. This of all others would seem to be the most befitting time for day-dreaming, reading, and renewing rest for both body and mind; and is, moreover, the one par excellence for the indulgencies of an angler’s heaven.

But, still later, comes “Jack Frost,” with his inimitable color brush, and tips all deciduous leaves with brightness; and so dyes and transforms the landscape that one impressively and con scientiously feels that this, above all others, is the best season to visit Yo Semite. Then, as though all nature was in fullest sympathy with such transcendent loveliness, every stretch of still water, in lake or river, doubles every wondrous charm by reflecting it upon its bosom, so that every bush or tree that may be struggling for life in the narrow crevices of the mountain walls around, are all most faithfully mirrored.

Then, the glorious fact should not be overlooked, that the marvelous mountain walls, and spires, and domes, are always there; and, being there, are, in themselves, an all-sufficient recompense without any supplementary accessories whatsoever. It will, therefore, and at once be seen that my statement is both correct and conclusive, that the best time to visit Yo Semite is “that which best suits your convenience,” all others being merely a matter of taste.

There is, however, one season, apart from all others, when it is next to impossible, for the average traveler, at the present, to visit Yo Semite, and that is in the depth of winter. Therefore, as this cannot be conveniently witnessed, and as the writer, with his family, spent many there, as narrated on pages 141, 142, he feels that this work would be incomplete without a brief outline of

THE YO SEMITE VALLEY IN WINTER.

| |

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Photo-Typo by Britton & Rey, S. F. |

| The Advent of Winter at Yo Semite Valley. | |

| (See page 493.) | |

As intimated on pages 347, 348, snow begins to fall early in November, but this soon disappears before the delightfully balmy Indian summer which succeeds, and which continues with but little intermission, both days and nights gradually growing colder, until late in December, when a light fleecy film commences to drift across the chasm from the south—the usual quarter for rain in California—which soon begins to intensify and deepen; then, large dark masses of cloud begin to gather beneath the lighter strata, with occasional stretches of sunlight sandwiched in be tween the different layers. At intervals those dark masses of cloud break into fragmentary patches, when a lambent sheen illumines all their edges with a golden glow; then the wind in fitful gusts commences to toss them into different shapes, seemingly in playful preparation for marshaling all these aerial forces into line, before making the final swoop upon the sleeping Valley. Nearly every rain or snow-storm in the Sierras is heralded in by a strong, squally wind; and the same phenomenon is generally ob servable when marching it out. Soon thereafter broad belts of cloud come sweeping down among the mountain peaks, “Like a wolf on the fold,” probably just as night closes in; then how steadily does the rain or snow fall down!

THE GREAT FLOOD OF 1867.

On December 23, 1867, after a snow fall of about three feet, a heavy down-pour of rain set in, and incessantly continued for ten successive days; when every little hollow had its own particular water-fall, or cascade, throughout the entire circumference of the Valley; each rivulet became a foaming torrent, and every stream a thundering cataract. The whole meadow land of the Valley was covered by a surging and impetuous flood to an average depth of nine feet. Bridges were swept away, and everything floatable was carried off. And, supposing that the average spring flow of water over the Yo Semite Fall would be about six thousand gallons per second, as stated by Mr. H. T. Mills,* [ * See page 376. ] at this particular time it must have been at least twelve or fourteen times that amount, giving some eighty thousand gal lons per second. Large trees, that were four to six feet in diameter, would shoot, endwise, over the lip of the upper Yo Semite; and, after making a surging swirl or two downwards, strike the unyielding granite and be shivered into fragments. At this time our family, consisting of two of the gentler sex, two young children, myself, and one man-servant, were the only residents of the Valley. The latter named, was dreadfully exercised over it, as he feared that the last day had come, and the world was about to be destroyed the second time by a flood! Immense quantities of talus were washed down upon the Valley during this storm,—more than at any time for scores, if not hundreds, of years, judging from the low talus ridges, and the timber growth upon them. After this rain-storm had ceased, a wind sprung up, and blew down over one hundred trees. In one spot of less than seven acres twenty-three large pines and cedars were piled, crosswise, upon each other.

Alas! at such a time, how fortunate the man or woman who has a cozy cabin, with an open fire-place; plenty of fire-wood, an abundance of provisions, books, agreeable companionship, and pleasant occupation. The beating of the storm upon the window panes, its heavy rain-drops on the roof, or the silent footfall of the fast deepening snow, with such surroundings, have no appalling terrors for him. But—to the benighted traveler, far from home and shelter, what? “God help him!” will be the spontaneous ejaculation of every earnest and feelingly humane heart.

Morning dawns, and the feathery crystals are still falling rapidly; the day rolls slowly on, and night again drops down her curtain, yet still it snows. Day follows day, and night succeeds night, for many days and nights, perhaps, without the least cessation of the storm. I have known eleven feet of snow to fall without the shortest intermission. But, finally it comes; and, while hostilities are suspended, let us take one lingering look upon our fairy-like surroundings on the outside. Believe me, the scene without seems like

A WORK OF ENCHANTMENT.

|

| THE NORWEGIAN SNOW-SHOE USED AT YO SEMITE IN WINTER. |

And we intuitively ask, “Is this, verily, the same spot of earth upon which we looked previous to the advent of the storm?” Alas! how changed. Every twig is bent down, every branch laden, and every tree covered with the silvery garment.

Along every bough most delicately reposes a semi-translucent frosting of snow, with diamond settings between the forks of each and every twig or branch, which, when the sun shines upon them, or rather through them, lights them up with a frosted glory that seems more like the creations of some wonderful Magi, by ages of labor, than of crystallized water within a night or two. Then, to look upon and up the mountain walls that surround the marvelous Valley, and see every bench, and shelf, or jutting rock; every lofty peak, or noble dome; and every sheltering hollow filled with snow. Can artist or poet, painter or writer, do justice to such a scene? Alas! no.

| |

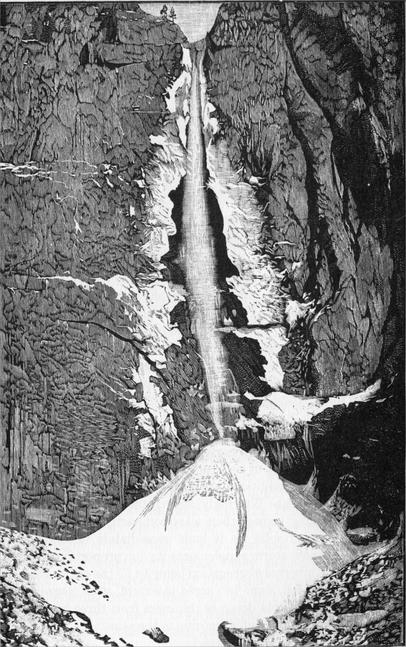

| Photo by Geo. Fiske. | Engraved by J. M. Hay, S. F. |

| ICE CONE OF 550 FEET, BENEATH THE UPPER YO SEMITE FALL. | |

Speechless with admiration, even while we are gazing upon it, a new revelation dawns upon us, for everywhere around we near rushing, rattling, hissing, booming avalanches come shooting from the mountain-tops, adown precipitous hollows, and creating fresh sources of attraction; with new combinations of impressions, that must be alike diverting and satisfying to both artistic and poetic feeling. Then, before these sounds can have been repeated in echoes, and hurled from wall to wall, or from crag to peak, another avalanche makes the leap; and, like its predecessor, indicates the birth of a new water-fall, in some strange and unheard-of place.

THE YO SEMITE FALL IN WINTER.

On every frosty night immense masses of ice fringe both sides of every water-fall at Yo Semite; the upper Yo Semite most noticeably so. Icicles over a hundred and thirty feet in length, and from fifteen to twenty-five feet in diameter, are often seen; and which, when illuminated by morning sunlight, scintillate forth all the prismatic colors. These, however, resplendently brilliant and beautiful as they appear, have but a brief existence, inasmuch as the same sunlight that creates such gorgeous hues, melts away their frozen shackles, and drops them down, thunderingly, many tons in a minute; and before the echoes of one reverberating peal have died away others keep following in rapid succession, until every fragment of ice has peeled off and fallen.

This being repeated nearly every bright winter’s morning, causes vast quantities of ice to accumulate at the base of the fall; to which constant additions are made of infinitesimal atoms of spray, that percolate filteringly among the broken icicles, and which, by freezing, cement them all so compactly together that an enormous cone of solid ice is built immediately beneath it, to which every snow-storm supplements its due proportion. The net results of this hibernal aggregation being to fill the entire basin at the base of the fall, some ten acres in extent, with consolidated ice; and which varies in depth or thickness from three hundred to five hundred and fifty feet, according to the season. In 1882, when the photograph was taken from which the accompanying engraving was made, it was at the maximum stated.

When the spring thaw in the mountains commences in real earnest, a vast sheet of water shoots over the top of the fall wall, down upon this cone of ice, in which it soon excavates a basin; and when this is cut out to a depth of from twenty to fifty feet, the entire fall leaps into it, and at once rebounds in billowy, volumes of cloud over a thousand feet; and, when the sunlight strikes this seething, eddying mass of comminuted spray thus rising, it lights it up with all the colors of the rainbow and presents one of the most gorgeous spectacles ever seen by human eyes.

The constantly recurring scenic revelations at Yo Semite lead us, in worshipful admiration as we say farewell, to breathe the beautiful words of Moore:—

“The earth shall be my fragrant shrine!

My temple, Lord! that arch of thine;

My censer’s breath, the mountain airs;

And silent thoughts, my only prayers.”

|

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/in_the_heart_of_the_sierras/29.html