|

|

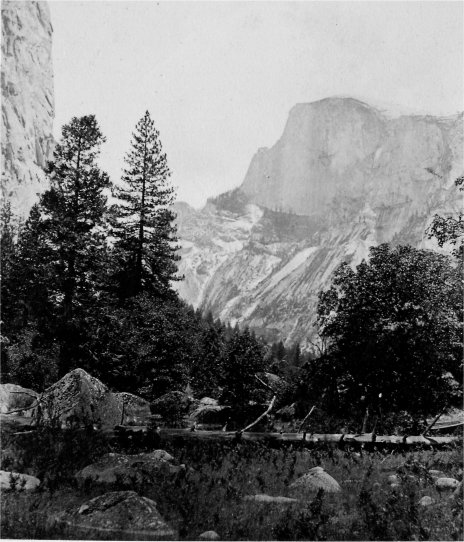

HALF, OR SOUTH DOME.

(1½ Mile high,) from head of Valley. |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Wonders > Central Pacific RR >

|

At Ogden the traveller takes the Utah Central Railroad, going south, and after a two hours’ ride, of thirty-five miles, arrives in Salt Lake City, the temporal and spiritual head-quarters of President Brigham Young.

Surrounded as is Salt Lake Valley by lofty mountains, and cut off from civilization by a thousand miles of barren and almost impassable deserts, it is certainly a very remarkable instance of human industry, perseverance, and devotion to what they regarded as a divine precept, that the Mormons should have established such a prosperous community in this unpromising region. Salt Lake City was founded in 1847; it is situated in latitude 40 deg. 46 min. north, and longitude 112 deg. 6 min. west, at the base of the western slope of the Wahsatch Mountains, which you pass by the Echo and Weber Cañons.

The history of the rise and progress of this strange sect cannot be entered into here. Suffice it to say that it was organized in 1830 by Joseph Smith, in Ohio, under circumstances savoring strongly of delusion and fanaticism, if not of deception; it afterward removed to Jackson County, Missouri, and then to Natuvoo, Illinois, on the Mississippi. Persecuted for obvious reasons in 1844-45, the Mormons emigrated in 1846, under President Brigham Young, the successor of Joseph Smith, who, with his brother Hyrum, was murdered by a mob in 1844. Persecution followed them through Missouri and Iowa, and they reached Great Salt Lake, after much hardship, in the latter part of July, 1847, passing up the left bank of the Platte River, crossing at Fort Laramie, and over the mountains at the South Pass. In 1850 Utah was admitted into the Union as a Territory, though it applied for admission as a State under the name of “Deseret.”

The city is four miles long and three wide, the streets—it right angles to each other, 132 feet wide, with sidewalks of twenty feet. Each house is twenty feet from the line of the street, and is adorned usually by shrubbery and trees; water is brought from the mountains, and its fresh current runs freely through the gutters of the streets, with a sound and sight very refreshing on a hot day, is you walk along tinder the grateful shade, over the sidewalks. Most of the houses are of adobe, or sun-dried brick and wood, and a few of stone. The stores are well supplied with goods from the East, and with excellent articles of home manufacture, which the saints are, in a measure, forced to buy—the trade of the Gentiles being with each other and with strangers, and not much with the Mormons. The Mormon stores, generally co-operative, are known by the sign, “Holiness to the Lord.” Church and State are closely united, the heads of the church being also the high civil officers. One-tenth of all a convert has, lie pays, it is said, into the “Treasury of the Lord,” and one tenth of his yearly profits, and devotes one-tenth of his time for public works—resembling the system of tithing of the ancient Israelites. There is, besides, a tax on property for the revenue of the civil government. Outward prosperity, peace, and contentment, seem to reign; poverty is unknown; crime is rare, and severely punished, and the ordinary vices of our large cities are not seen, and most likely do not extensively exist—the one great evil, as we deem it, polygamy, swallows up all lesser vices by taking away one great incentive. The Mormons regard their prosperity as a sign of the favor of heaven; but outsiders more truly ascribe it to their industry, discipline, and concentration of energies on one purpose. Whatever may be thought of their religious views and consequent practices, they are undoubtedly sincere. The President is a man of remarkably clear mind and sound sense, and with great executive ability, equal to his responsible position; sincere and active in everything which he considers good for the moral, intellectual, and material elevation of his people, whose confidence he fully enjoys. He is of commanding appearance, affable to strangers, and impresses you with the idea of strength, firmness, and resolution, which indeed are required to keep this anomalous community from falling, to pieces by the slow but continual sapping of its foundation-tenets by the encroachments of Eastern principles.

The “spiritual-wife” system, which now seems tottering to its fall, was not an original tenet of the Mormon creed, forming no part of the teachings of its founders; and probably would long since have met the fate deserved by such an abomination, had it not been in great measure kept out of public sight by the remoteness and isolation of this people. Even now, when public indignation is aroused for its extinction, the problem is a difficult one to solve in a way which shall punish or restrain the guilty ones in high places, without causing unmerited suffering to the deluded wives and innocent children.

I have before me the “Third Annual Catalogue” of the “University of Deseret,” in Salt Lake City, for the years 1870-71. It contains the names of 580 pupils: 286 males, and 294 females, with those of 13 instructors. The courses of instruction in the classics, in the sciences, and in the normal studies, will compare favorably with those of our Eastern colleges, and seem admirably adapted to prepare the way for a better state of. things, evidently now approaching rapidly, and to develop the great natural resources of this country. With a fertile soil, healthy climate, and inexhaustible mineral wealth, this land of beauty and grandeur must soon be the pasture and the mine, as it is the highway of the nation. Time only can solve the questions of statesmanship, civil polity, religion, and morality, presented by this singular community, whose centre is at Salt Lake City. When the iron will which rules this people ceases to exert its influence, the Mormon system will doubtless crumble away before the advancing tide of Eastern civilization, now so rapidly surrounding and permeating it by means of the Pacific Railroad; yet, whether its life be long or short, this sect has made a pathway and a stopping-place for the westward march of the nation, and thus, involuntarily, have greatly advanced the progress of humanity. The city is beautifully situated, and, as seen from the surrounding hills, its so-called “Valley of the Jordan” is a perfect garden in the wilderness. With and without irrigation the crops are fine, and the fruit is excellent; the grasshoppers are a great plague, and sometimes so utterly destroy a growing crop as to require planting even a third time. Camp Douglass overlooks the city, and, in case of need, could soon shell out an enemy. The valley was evidently once the bottom of an inland sea, as proved by the terraces, which can be traced for miles along the sides of the mountains, indicating former levels of the water; it contains over 1,100 square miles, with much fine grazing, as well as cultivated, land. Mormon industry has shown that reclaimed and irrigated sage plains make very fertile soils; the disintegrated felspathic and limestone make a rich, porous, and absorbent earth, if well watered. The Mormons now manufacture almost everything they use, even to articles of silk; the precious metals, coal, iron, and building, stones are abundant, and the water-power for machinery is ample.

The Tabernacle will hold about 10,000 persons; it is the first object seen when approaching the city— its bell-shaped top looking like a balloon rising above the trees; the building is oval, 250 by 150 feet, the roof supported by forty-six columns of sandstone, from which it springs in one unbroken arch, said to be the largest self-sustaining roof on the continent; the height on the inside is 65 feet. It contains an organ, second in size only to the Boston organ, made by a Mormon in Salt Lake City. The seats are plain, those of the men and women separate. The foundations of the great temple are laid in granite, and are now even with the ground, above which it is doubtful if they rise the building was to cover about half an acre, and to be one of the grandest church edifices in the country; the main structure 100 feet high, with three towers on each end, the central one 200 feet high. The fine granite of which it was to be built resembles the Quincy sienite, but is much whiter; it is found in abundance in the neighboring mountains. The theatre, city hall, and council house, are fine structures, and many of the stores compare favorably, both inside and out, with our own.

Though Capt. Stansbury, in 1850, mentions seeing myriads of wild geese, ducks, and swans on the surface of the lake, I saw nothing but a few ducks and snipes around the edges, scarcely disturbed by the noise of the train. The shore is naked and bleak, and there are none of the invigorating breezes of the ocean coming from its vast and motionless expanse. Except the valleys at the southern end of the lake, the country seems very barren, without fresh water, and so little elevated above the lake that a rise of a few feet in its waters would flood an immense extent of country—the only use of which would seem to be, in the language of Capt. Stansbury, that, from its extent and level surface, it is good for measuring a degree of the meridian. The lake is said to be rising annually, and the Salt Lake problem may ere long be solved by geological agencies, the people being actually drowned out.

The existence of a salt lake ini this region has been known for nearly two centuries. The water is so salt, that twelve hours’ immersion will so far corn beef that it can be kept without further care, even when constantly exposed to the sun; in a few days it may be made perfect “salt junk”; if the meat were only there, a “Salt Lake Meat Preserving Company” might profitably be established near these waters. There is no life in the lake, and beat little in the surrounding brackish waters, so that pelicans and gulls which breed on the islands must go at least twenty miles for food for themselves and young. The water, from its density, is very buoyant, as in the Dead Sea; it is easy to float in it, but hard to swim, from the tendency of the legs to come up and the head to go down; the brine irritates the eyes, and almost chokes you if accidentally swallowed; the most expert swimmer would soon perish in its heavy waves. It contains more than twenty per cent. of pure salt, with very little impurities; if the people are not the “salt of the earth,” the water is, and probably ere many years this region will be the seat and the source of a profitable and extensive industry from its natural salt works.

After leaving Ogden, and pursuing your way westward on the Central Pacific Railroad, you pass through a well-cultivated Mormon country, getting fine views of the lake, near which the track passes for miles. In nine miles you arrive at Corinne, a lively gentile town, the centre of valuable mining interests in the neighboring territory of Montana on the north. After crossing Blue Creek on a trestle bridge 300 feet long, over many sharp curves and through deep cuts, you come close to the graded bed of the old Central road, which ended at Ogden and is now unused. Here you begin to rise till you get to Promontory Point, one of the most difficult passes on the road, and near where the trains from the east and the west met May 10, 1869, when the last tie was laid which bound the Atlantic to the Pacific. This was certainly one of the most remarkable events in the history of travel; we all remember how the country rejoiced, some cities quietly and economically, like Boston, others noisily, and with generous and hospitable exultation, like New York and Philadelphia, when the message flashed over the wires on that day that the last spike was driven; the President of the road stood there in the wilderness holding in his hand the silver hammer to whose handle was attached the telegraph wire, and when he struck the golden spike at noon, the joyful news went on lightning wings to every city of the land; the locomotives screamed and rubbed their sooty noses together, and the crowd huzzaed, shook hands, drank toasts, and exhibited the hilarious and almost frantic transports peculiar to such occasions outside of staid New England. This point is fifty-three miles from Ogden, 1,084 from Omaha, and 2,730 from Boston.

At 100 miles you are about in the middle of the “Great American Desert,” where the eye searches in vain for signs of animal or vegetable life; alkaline beds, sandy wastes, and rocky hills, constitute the landscape; this desert was once evidently the bed of a great salt lake, and such as would be presented were the present Utah and Great Salt Lakes to be drained, and raised to the same level.

In 150 miles you leave Utah, and enter Nevada Territory, and at Toano, 183 miles, you enter the Humboldt division of the road, ascending the desert by the Cedar Pass to Humboldt Valley, at Pequop, being on the third high point, 6,210 feet above the sea. From this there is a gradual descent, along which you obtain fine distant views of the beautiful valleys in the range, well supplied with lakes, and famous for their fine crops. The celebrated Humboldt Wells are 218 miles from Ogden; here the emigrant trains used to stop after the hard journey across the desert; there are about twenty wells, in a charming valley, in which the water rises to the surface, slightly brackish; they are exceedingly deep, and are evidently craters of extinct volcanoes, whose existence is proved by the broken masses of lava and granite all around. This valley, which seems like Eden after crossing the dry and dreary desert, is named from the Humboldt River, which, rising in the neighboring mountains, runs through it; the track follows the river for many miles. At Elko, 275 miles, stages may be taken for the famous White Pine District; Treasure City, 125 miles to the south, is the centre of extensive gold and silver mining. At Humboldt Cañon, or the Palisades, about 300 miles, the scenery is fine, much like that of the Echo and Weber Cañons on the Union Pacific Road, but more dismal from the greater bleakness and bareness; it is gloomy and grand from the furious river which rushes along in the deep gorges. A peculiarity of the rivers here is that they spread into shallow lakes, and in summer disappear in what are called “sinks”; probably most of their water escapes by the great evaporation, though there may be in some cases a sinking into a subterranean channel, or into the absorbent sand.

As the Truckee region is approached, fine growths of timber begin to appear, clothing the slopes of the Sierra Nevada range, which you now begin to ascend; the river is extremely pretty in its rocky bed, though much of the beauty of the scenery is lost, unless the moon be shining, by passage in the night and early morning. At Reno, 590 miles, you may take the stages for Virginia City and Gold Hill, Nevada, where are the famous Ophir and Comstock silver mines. Soon after passing Verdi, following along the numerous curves of the river, and crossing several picturesque bridges, at 610 miles, you enter California. You are now ascending all the time, amid grand scenery, with mountains on each side, timber-clothed ravines, and here and there a strip of meadow. At Truckee, 623 miles from Ogden, and 120 from Sacramento, you are above 5,900 feet above the sea; this is the centre of a great trade in lumber, as the best of material is abundant and accessible, and the water-power ample. Here you may start for Lake Tahoe, a beautifully clear sheet of water, very deep (in some places 1,700 feet), twenty-two miles by ten; it is part in Nevada, and part in California; this is the lake which Mark Twain so extols above the Italian lakes in the “Innocents Abroad,” to which admirable burlesque the reader is referred for fuller description. Donner Lake, smaller, but as beautiful, and seen from the track, has a melancholy interest, from the domestic tragedy connected with it; here, in the early times of immigration, a party from Illinois were hemmed in by the snow; most escaped, leaving a Mr. Donner, his wife, and a German; when a party reached the place the following spring, Mr. Donner had died, and the German is said to have been found eating a part of Mrs. Donner’s body, whom it is believed he murdered. Both these lakes are probably in craters of old volcanoes, closed by some geological convulsion which has occurred in the Sierra.

The summit of the range is fourteen miles distant, and the doubling of the locomotives shows that work is to be done; up you go constantly, getting glimp[s]es of the lake and the mountains, till you get to the provoking snow-sheds, which for forty miles protect the road from avalanches of snow, but not of hard words from travellers, who are by them deprived of the magnificent views. You cross the range at Summit, 7,242 ft. high, 1,700 miles from Omaha, and 105 from Sacramento. The peaks of the Sierra are far above the level of the Donner Pass, and are here and there covered with snow. The Summit Tunnel, the longest of several, is 1,700 feet, nearly one-third of a mile; the forty miles of snow-sheds, of solid timber, are said to have cost $10,000 a mile. You are now descending all the time, sometimes quite abruptly. Just after leaving Alta, sixty-two miles from Sacramento, you enter the “Great American Cañon,” one of the grandest in the Sierra, where the rocks, 2,000 feet high, give a narrow passage to a branch of Feather River; the scenery is very fine, and there are no sheds to intercept the view. Here you come to a succession of strange names, suggestive of the lively times of twenty years ago,—such as Dutch Flat, Little York, You Bet, Red Dog, Gold Run, Cape Horn. This is the region of hydraulic mining, and you see ditches and flumes, with rapid streams from the mountains running for miles to various claims, and then directed through discharge pipes with great force against the gold-containing bank, washing away immense amounts of dirt into the long channels, where the gold gradually settles from its greater weight. Chinese miners and their cabins frequently meet the eye. Going rapidly down, almost on the edge of a precipice 2,500 feet deep, you come to and double Cape Horn, the road cut into the very side of the mountain by the Chinese it makes one shudder to think of the consequences of the train getting off the track as it rushes with frequent screams down the steep and narrow line, around the sharp curves, and over the apparently delicate bridges; if quicker, it is perhaps more dangerous than doubling the point of South America. Let us hope that familiarity will not breed contempt of danger, for inevitable destruction would be the result of an accident here.

The fine fruit, bottles of wine, grapes, and grain fields show that we are in one of the great valleys of California. We soon rush into Sacramento, only fifty-six feet above the sea, having descended over seven thousand feet in one hundred miles. Sacramento is the heart of California, depending on its never-failing agricultural and mineral resources; while San Francisco is rather a great commercial market, constantly fluctuating, and as much injured by the Pacific Railroad as Sacramento, the capital, has been increased by it. It has suffered greatly from floods, from the filling up of the river by the results of mining operations; but it is now raised fifteen feet above the highest level of the river, and is now considered safe from floods. Thence to San Francisco, via Stockton, over the Western Pacific Railroad, is 138 miles; thus, the distance from Boston to San Francisco, nearly 3,600 miles, may be passed over, if necessary, in seven days.

The Pacific Road was in running order seven years before the limit of the construction time, the track having been laid, and well laid, at a rate before unparalleled. In twenty-two hours, on the Union Pacific Road, seven and a third miles were laid; and on the last day but one, May 8, 1869, the Chinese laid, on the Central Pacific road, ten miles of track in twelve hours. When we remember that the great road from Vienna to Trieste, over the Soemmering Pass, less than three hundred miles, and with an elevation of only 4,400 feet, required fifteen years for its construction by the Austrian Government, with all the advantages of a populous country, and then consider that our road, more than six times as long, rising nearly twice as high, and built through a waterless, woodless desert, infested by hostile Indians, by private enterprise was completed in seven years, it is truly marvellous, and a convincing proof of the wonderful energy and foresight of the American people. The completion of this road not only unites the Atlantic and Pacific, changing the course of commerce from the East Indies, but opens vast resources of our country’s agricultural and mineral wealth, and brings within the reach of travellers and invalids the magnificent scenery and bracing air of the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada—leading to the great natural wonders of the parks of Colorado, the Salt Lake Valley, the Yosemite Valley, with its waterfalls and stupendous heights, the giant trees, the splendid Pacific shores, the beauty of the coast ranges, and the marvels of the Columbia River and the Cascade Mountains.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/wonders_of_the_yosemite_valley/02.html