|

|

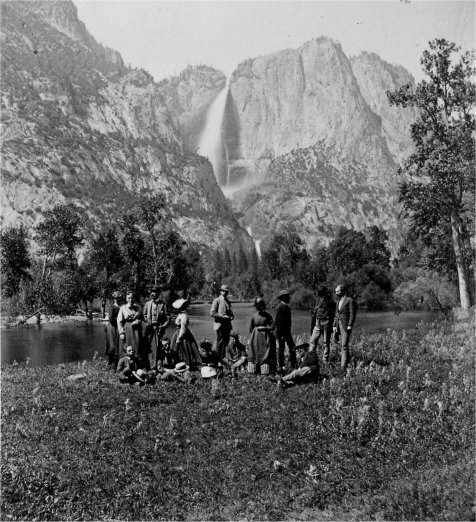

YOSEMITE FALL.

2634 feet high. |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Wonders > Yosemite Fall >

|

The distance from Stockton to Mariposa is about ninety miles, and from there to Clark’s about twenty-five, or 115 miles by stage or carriage, and then twenty-five more on horseback to the hotels in the valley—or 140 miles, carpet-bagging from your base at Stockton, which, last year, was the nearest point by rail; though probably even Mariposa will ere long be reached by rail, and a carriage-road be made twelve miles beyond Clark’s, reducing the terrible horseback ride to twelve or thirteen miles. Rough as it is, many ladies accomplish it every year. A railroad has now been finished from Stockton to Copperopolis, reducing the stage ride by Coulterville about twenty-eight miles.

We left Stockton in a light carryall, with two horses, at six o’clock in the morning, intending to take our own time for the journey. On getting into the country, everything looked burnt (this was in the last half of July); the clayey soil was cracked in all directions by the heat, sometimes to a foot in depth, presenting very much the appearance of the geological mud-cracks so frequently seen in the rocks filled with a harder material. The crops were all stacked in the fields, immense piles, no barns being necessary to protect the grain at this dry season, and there they remain till the steam-thresher comes along, and the threshed grain is placed in sacks, loaded into wagons, and transported to the river or the cars. The scarcity of water at the surface gives an indescribable parched appearance to the landscape; yet there seems to be an ample supply at a moderate depth, and every farm has its wind-pump, raising water from a kind of Artesian well, distributed by gutters over the fields and gardens. The interminable barren plain. dotted with herds of cattle and horses driven by their herdsmen, the long trains of grain-laden, creaking wagons, drawn by mules, with the numerous wind-pumps lazily and noisily working, remind one of the Spanish landscape, and it would have been entirely in keeping, with the surroundings to have seen Don Quixote and Sancho Panza ride forth from a court-yard. The squirrels ran out from their burrows by the sides of the road, and scampered across the fields, and occasionally a long-eared, diminutive, half-starved-looking hare would be seen picking up a scanty meal among the stubble. As we got into the country, or rather desert, for it was a hot, treeless, sandy plain, the squirrels became more numerous, apparently in inverse proportion to the amount of visible food, accompanied by the grave-looking burrowing owls which inflict their presence, the other side of the Rocky Mountains, on the prairie dogs; horned lizards were not uncommon, lively and plump, but what they found to eat I could not discover, as insect life seemed to me decidedly scanty; they may find ants, as now and then their hills were to be seen. These plains are remarkable for their mirage, and it is impossible at first to believe that the lake in advance, with its grateful shade of trees, is nothing but deception and reflection from the sand, with here and there a scraggy tree. You meet no travellers on foot except a few Chinese, dressed like ourselves, except the hat and blouse, going to and from the mining locations; and even they frequently exchange money for time, and ride by stage. Wherever a clump of trees appears, the woodpeckers and magpies are numerous, and the wild pigeons are hardly wilder than the pigeons in our streets. The oaks are beautifully festooned with a long, hanging moss, giving the same funereal look that a similar appendage does to the cypress swamps of the Southern States; unlike the latter in most respects, it also prefers dry and sandy plains instead of moist places, and is confined, as far as I saw, to the oaks. The Stanislaus and Tuolumne Rivers are crossed by ferries, moved by most primitive hand-power; “pay or stay” is the word there, and a ferry-man is even more imperturbable than the keeper of a turnpike; if travellers were numerous, the delay and the changes would be a great nuisance, and the only way to get over the difficulty would seem to bridge it.

The dust and the heat were overpowering; and, much as we suffered, the horses suffered more; but if a horse gives out there are plenty of others, and in some of the corrals there were so many that the owner did not positively know how many he had. After dinner one of the horses was used up, and with a fresh one we started again, contrary to the advice of the driver, who was not sure of his way by night, and rode consequently till midnight, having lost our way as far as the path was concerned, but sure of coming out all right by keeping the pole star over our left shoulder, as you can ride anywhere on this level plain just as you can upon a prairie. We arrived at Snelling’s at midnight, and, after sleep rendered unrefreshing by public snoring and foul air, with the additional discomfort of a very poor breakfast, we began the second day, equally hot and even more dusty, but more interesting as the region became hilly. At noon we had reached Hornitos, well named, as it is truly a “little oven,” and gave us a good baking; passing from this through Bear Valley, you traverse the famous Mariposa Estate, where fortunes have been lost and won; the former rich gold placers have yielded up their wealth, and the region is in a state of decay, given up principally to Jews and publicans, and the Chinese; the latter patiently, and laboriously, and successfully digging over the old sites, already dug over many times before; yet with their sobriety, economy, and perseverance, picking up many a “chispa” (or sparkling bit of gold) overlooked by the more hasty American diggers. There is, I believe, only one stamp mill on this immense property, and that not doing much. Deserted huts, dilapidated flumes, broken mining apparatus, and desolate heaps of stones, speak sadly of the crowds that have departed without the treasure which they sought; in fact, the whole region, especially near the watercourses, has been dug over, and looks like a violated graveyard, fit emblem of the bright hopes there buried. The only sign of life is indicated by the turbid streams, often only a few inches deep and wide, discolored by the washings of the indefatigable Chinese, not far off.

At Mariposa, which is situated in a charming valley, though at this season very dry, hot, and dusty, we found another relic of the olden time in a double wheel of about twelve feet diameter, and two feet wide, covered with lattice-work, set up in the back-yard of the principal hotel. In this was gravely walking, as in a treadmill, a large dog, turning the wheel slowly, thus acting upon a pump which supplied the water for household purposes—somewhat in the manner of the dog-turnspit of old. The work seemed easy, and the dog was sleek, and apparently contented to perform his welcome duty for the house.

Here you start by stage or your own conveyance, for the higher hills, for White and Hatch’s, twelve miles distant, 3,000 feet above the sea; after a good meal and welcome rest there, you start again for the mountain region, and very soon come among the tall pitch pines, with their grateful balsamic odor, and ascend nearly 3,000 feet more in about seven miles, and then rapidly descend in four or five more, by a good but very zigzag road, 1,700 feet to Clark and Moore’s, the real starting-point for the valley and for the Mariposa Big-Tree Grove. You generally arrive here in the evening, and the coolness of the air and water are very grateful after the heat, and dust, and jolting of the day; the house is kept by New England people, and you are received in the most hospitable manner, and nothing is wanting to make you comfortable. Mr. Clark is the guardian of the grove, appointed by the State. You here, if you wish, mount your horse for the grove, about four miles distant; but of this I may speak on another occasion; here also is the south fork of the Merced River, inviting you to a bath in its clear cool water, and very few, I think, decline the invitation to get rid of the accumulated dust of the journey from Stockton. The hotel is about on the same level as the Yosemite Valley, but many a weary mile and aching muscle intervene, for here you take horse. Leaving early next morning, you cross the river, and in about four miles ascend 1,900 feet, where you cross Alder Creek, stopping to give yourself and horse a drink. You then ascend to Empire Camp, now used only as the house of the tenders of the sheep here kept; we went through one flock containing several thousand, and the dust they kicked up was suffocating, as it was quite impossible to go on without trampling upon them in the narrow path, until the flock had passed; the grizzlies must have fine pickings among them. We met, also, horses by the score, running wild, turned out to recover from the fatigue of carrying, pilgrims like ourselves, and many very much heavier, up and down these terrible hills. You then, after about twelve miles, arrive at the half-way house, or Perigo’s [Editor’s note: Peregoy’s—dea.] , 3,100 feet above Clark’s, and 7,100 feet above the sea; here frost appears early in August, preventing the production of any useful crops, but apparently admirably suited to the chipmunks, or striped squirrels, which run in and out the sheds and houses like mice. The guides and horses are obliged to remain out of doors at night, the former consoling themselves by a large bonfire. From this you may branch off to “Sentinel Dome” and, “Glacier Point,” though it is better to make this trip after you have seen the valley, as it is better enjoyed after you know what you are looking at—it is like a review of a subject previously studied, the principal points of which cannot be understood or appreciated until you have personally examined the whole field of observation.

Going forward, then, you enter Westfall’s Meadow, a very dangerous place out of the path, even in the dryest time of the year, from the liability of miring or even drowning your horse, and perhaps yourself—it lies in a basin between two high ridges, and is never dry. By day the wind blows up the mountains, and by night down; you have the dust, therefore, always with you going up, and also going down if any one be in advance of you; this dust is the greatest annoyance of the trip. When you have ascended 3,426 feet above Clark’s, or 7,400 feet above the sea, you come suddenly to what is called “Inspiration Point,” and there the magnificent panorama of the valley at once, and for the first time, bursts upon the view; no language can describe its grandeur, and no painting can do it justice; the best idea is given by the excellent photographs which have been taken from this point, but even these are poor in comparison to vision, and serve rather to recall features once seen than to depict the great reality. It is well called “Inspiration Point,” for it is an inspiration even to those familiar with the grandest mountain scenery; it is probably the most magnificent view to be had in the world. Having reached this point, where the exploration of the valley really begins, what is seen in the valley will better be described on another occasion; and I will only add a few remarks, which may be interesting to those who intend or hope to visit it, comparing the advantages of the two principal routes, the Coulterville and the Mariposa. By the Coulterville route which enters the valley from the north, you have more and finer views of the distant Sierra to the north and east, and see the various points of beauty in succession; by the Mariposa trail, you go near the big trees, and the whole grandeur of the Yosemite is revealed at Inspiration Point; if you return by the Mariposa route you get a second view, or rather review, as a whole of what you have visited in detail, and, besides, can easily make the grand trip to the Sentinel Dome and Glacier Point, the view from which is nearly as grand, perhaps, as that from Inspiration Point. If one prefers to try both, enter by all means by the Coulterville, and leave by the Mariposa route. As to public conveyances, you leave Stockton at six a. m., and reach Hornitos about eight p. m.; starting next morning, you arrive at Mariposa at noon, and at Clark’s at night. There, next morning, you take horses for the valley, distant twenty-five miles, and do it in one or two days, according to the tenderness of the parts of the body which rub against the saddle, and your experience as a horseman. You spend three days, at least, in the valley; then one to return to Westfall’s, where the trail goes off to the Sentinel Dome, which should not be omitted—one to Clark’s and the big trees—then two days by stage to Stockton again—in all eleven days.

If you go by private conveyance, it takes two days longer, with

|

But, with all its fatigue and discomforts, there is nothing in this trip to alarm the most timid person; there is no danger to the nervous system, but great fatigue to the muscles, whether riding or walking. Notwithstanding these drawbacks, I think no one who has made the trip will ever regret it, though he may not, till railroads are extended, be inclined to repeat it—when he remembers the grandeur of the scenery, the magnificence of the forests, the extraordinary beauty of the waterfalls, and the uncommon purity of the air and clearness of the sky in these elevated regions.

As the traveller is supposed to be left now at Inspiration Point, gazing into the beautiful valley, it may be well to allude to the sublime views from Sentinel Dome and Glacier Point, both above and on the edge of the valley. The Sentinel Dome is a great rounded smooth mass of granite, about five miles to the north-east of the half-way house of Perigo’s [Editor’s note: Peregoy’s—dea.] ; there are upon it a few stunted pines, and one remarkable one on the summit, a welcome support to cling to during the high winds which prevail there; you may ride to the very top; but most prefer to walk, especially in descending, so slippery is the bare rock. Looking north-east up the Tenaya Cañon, in which is one of the forks of the Merced River, and the beautiful “Mirror Lake,” you have on the left, in the distance, the snow-covered Mount Hoffmann, and almost under it the “North Dome,” 3,568 feet above the valley, the upper portion of the rounded, concentric-layered, granite mass before alluded to as the “Royal Arches,” inaccessible from the valley, but easily ascended, by a ridge which runs to the north; this magnificent dome is worthily supported by the Royal Arches, by the side of which man’s proudest architectural monuments are utterly insignificant. On the right, or south border of the cañon, is the “Half Dome,” with its stupendous vertical face of 3,000 feet from the summit, then a steep slope of about seventy degrees of 2,700 feet more, the top being absolutely inaccessible—beyond is the Clouds’ Rest, 700 feet higher, but belonging rather to the Higher Sierra than to the Yosemite group; on the opposite side is Mount Watkins, named from the eminent photographer of this region, and beyond this the distant Sierra. The Sentinel Dome is 4,150 feet above the valley, and the Half Dome is nearly 600 feet higher. To the east is seen the Nevada Fall, with Mount Broderick, or the “Cap of Liberty,” to the left of it; in the far distance the Lyell group, and to the south-east the steep, inaccessible granite peak, named after Starr King, belonging to the Merced group.

About half a mile north-east of the Sentinel Dome, and directly in a line with the edge of the Half Dome, is Glacier Point, overhanging the valley, and presenting a view which for beauty and grandeur is by many regarded as the finest around the valley. Both the Vernal and the Nevada Falls are in sight to the east, separated from each other about a mile, and the nearest one, the Vernal, a little more than a mile from the spectator; the point is fringed almost to the edge with Jeffrey’s pine. The view of the Half Dome, only two miles distant, and directly in line, is grand in the extreme. To the north is seen the Yosemite Fall, 2,600 feet high, and to the west, limiting the vision, is the massive El Capitan, a solid block of granite, 3,000 feet high, projecting squarely into the valley, with almost vertical sides. Below you see the green of the valley contrasting beautifully with the cold gray of the bare rocks, the tall pines looking like shrubs, and a man scarcely discernible. The thread of the Merced River sometimes glistens in the sun, and the garden of Mr. Lamon forms a pleasing feature with its greenness and orderly arrangement. Travellers who fail to visit this point, in my judgment, lose one of the finest views in the whole Yosemite.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/wonders_of_the_yosemite_valley/05.html