|

|

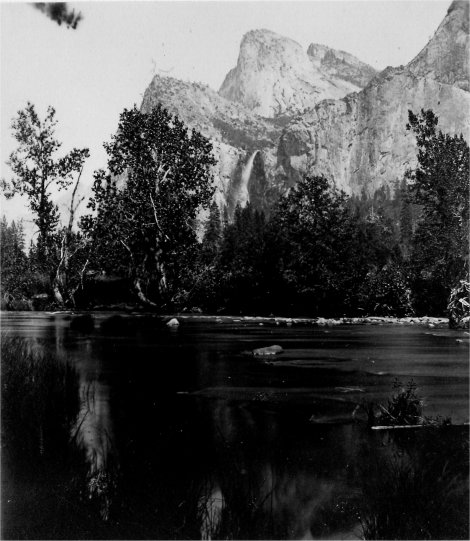

BRIDAL VEIL FALL.

940 feet high. |

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

Yosemite > Library > Wonders > Yosemite Valley >

This unique and wonderful locality, visited by the writer in July, 1870, was once the stronghold of the Yosemite tribe of Indians, who were expelled from it in 1851, and exterminated in 1852, by the whites, exasperated by their murderous attacks, and by the rival tribe of Monos. Before this time it was unknown to the whites. A few of these Monos now live in the valley, belonging to the so-called diggers, a miserable, drunken, and fast-disappearing, race, living chiefly upon fish from the Merced River, acorns, and the seeds of a species of pine, called the nut-pine.

The word Yosemite, meaning a large grizzly bear, was probably the name of a chief, who gave his name to the tribe, and the valley is now called by the Indians Ahwahnee, and not Yosemite; and even the latter is sometimes pronounced Yohemite by the Mexicans. It was first visited for curiosity or pleasure in 1855, since which time the number of visitors has annually increased, so that three hotels are now hardly able to accommodate them. It is a toilsome, fatiguing, and, in many respects, a very disagreeable journey, but when carriage-roads are extended, railroads built, and the trails made decent for horse and man, it may be undertaken by the most delicate and timid with safety and delight. It belongs to the State of California, granted by Congress, and accepted by the Legislature of the State, in 1864. There are some who lay claim to a considerable part of the best portion of the valley; and should they succeed in establishing their claims, the fleecing system of Niagara would be likely to prevail, and a price have to be paid for every trail, bridge, and advantageous point of observation. It should be under the sole control and management of the State; and the sooner the State takes the roads and trails in hand, the better for its own credit and the comfort of travellers.

On account of the chilly winds rushing in from the northwest through the “Golden Gate” to supply the place of the heated current, which ascends along the coast range, the summer (July and August) is the coldest, dampest, foggiest, and most disagreeable part of the year in San Francisco; so that, going eastward, you rise several thousand feet in all air actually warmer than on the coast, and on the highest part of the Yosemite range, 7,400 feet, it is even warm in midday in summer. At Clark’s Hotel, outside the valley, and at the hotels in the valley (each about 4,000 feet high), the thermometer indicated 80 deg. for six hours every day, though the nights were cool, but indescribably clear and exhilarating. At this season the traveller is sure of good weather, as rain is extremely rare, and clouds uncommon. One is impressed with the subtropical character of the vegetation on the Pacific in latitudes where, on the Atlantic, the flora of the temperate zone prevails; in Stockton, figs grow luxuriantly in the open air, and in one of the squares was a magnificent American aloe, at

|

Among, the health inducements for travel here are the invigorating air, the pure cold water, and the exercise, which, though often severe, cannot fail to strengthen an ordinary traveller, refreshed as he is, at night, by excellent food and comfortable bed; when to these is added the grand and beautiful scenery in this immense panorama of mountains, surely no further inducement is necessary for one to journey to this valley, brought within a week’s easy travel of the farthest Atlantic seaport. In the words of Prof. Whitney, “Nothing so refines the ideas, purifies the heart, and exalts the imagination of the dweller on the plains, as an occasional visit to the mountains. It is not good to dwell always among them, for ‘familiarity breeds contempt.’ The greatest peoples have not been those who lived on the mountains, but near them. One must carry something of culture to them, to receive all the benefits they can bestow in return. As a means of mental development, there is nothing which will compare with the study of Nature as manifested in her mountain handiwork.” Beside the grandeur of the mountains, and the stateliness of the trees, the most beautiful feature is the system of waterfalls, fed by the snow, which is seen glistening on the higher summits in midsummer; as the snow gradually lessens with the advancing summer, the volume of water diminishes, and, by July, some of the most beautiful, like the “Virgin’s Tears,” and the falls of the “Royal Arches,” and the “Sentinel Peak,” are entirely dried up, and even the great Yosemite, the Bridal Veil, the Vernal, and the Nevada Falls, are comparatively small by the month of August. The fact is simply alluded to here, as, in another place, more space will be devoted to this topic.

The mountains, which look so massive and uniform in outline in the distance, when approached, are found to be deeply cleft by valleys and narrow cañons.

This whole mountain system, called by Prof. Whitney the “Cordilleras,” is between the Pacific Ocean and 105 deg. west longitude including the Rocky Mountains proper on the east, and, as we proceed westerly, the Sierra Nevada and the broken region between, and the most westerly coast range.

Beginning on the Pacific, the coast ranges are geologically newer, according to the California geologists, than the Sierra Nevada, and have been subjected to great disturbances up to a comparatively recent geological period; there are in them no rocks older than the cretaceous, this and the tertiary making up nearly their whole body, with some masses of volcanic and granitic material, neither forming anything like a nucleus, or core. They have no lofty peaks in Central California, Mt. Hamilton, near San Jose, being only 4,400 feet, and Monte Diablo, so conspicuous from San Francisco, only 3,860. The scenery is picturesque, but not grand, and especially remarkable for the beautiful valleys, or parks, between the ridges, with magnificent forests of oaks and pines, the ridges being bare. North and south of the central region, the elevation is greater, even to eight thousand feet, but yet not within six thousand feet of Mt. Shasta, of the Sierra Range. The phenomena of erosion are well marked, it is said, and the atmosphere has the indescribable exhilarating property which so delights the traveller and strengthens the invalid.

The Sierra Nevada, or the snowy range, forms the western edge of the great continental upheaval, or plateau, on which the “Cordilleras” (as just explained) are built up; the Rocky Mountains form the eastern edge of the same plateau, the width between the two, traversed by the Pacific Railroad, being about one thousand miles. In this range the peaks are the highest, and the subordinate ranges the most regular. The base of the Rocky Mountains is four thousand feet above the sea level, with such a gentle ascent from the Missouri River that you hardly perceive it as you speed along for six hundred miles; but on the west side of the Sierra you descend very rapidly, and, in many places, apparently dangerously, seven thousand feet in less than a hundred miles to the level of the sea. The Sierra Nevada strictly belongs to California, being called the Cascade Range to the north in Oregon and Washington Territories, and to the south losing itself, more or less, in the coast ranges; from the Tejon Pass to Mt. Shasta is 550 miles, the last one hundred being the Cascade Range—the average width of the chain is eighty miles, taking in the lakes on the east and the foot-hills on the west. The western slope, in the centre of the State, rises one hundred feet in a mile, or seven thousand feet in a horizontal distance of seventy miles; in the southern passes the slope is much steeper than this. Donner Lake Pass, where the Central Pacific Railroad crosses the range, is about seven thousand feet above the sea; the crest of the range is five hundred to a thousand feet higher than the passes, or eight thousand feet high. The central mass is chiefly granitic, flanked by metamorphic slates, and capped, especially to the north, by volcanic materials; the activity of the subterranean forces is now indicated by occasional severe earthquakes, more severe and more dreaded than we in the east dream of, by hot springs and geysers, and by the existence of many well-formed, but extinct, craters.

The scenery of the “High Sierra,” as you stand upon the “Sentinel Dome,” or “Glacier Point,” is very different from that of the higher Alps. You see much less snow and ice, and no glaciers extending into the valleys. But the rocks, even to the edge of the Yosemite, are grooved and polished, showing the former existence of an immense sheet of ice. You see no grassy slopes between the forest and the snow, but the woods extend much higher up, and abruptly terminate with the bare rock in summer, and the snow line in winter; the trees are large, but sombre and monotonous, growing even at a height of 7,000 feet. Though there are many beautiful valleys along the streams, and magnificent waterfalls, the character of the scenery is rather grand, sublime, and awful, than beautiful or diversified; the heights are bewildering, the distances overpowering, the stillness oppressive, and the utter barrenness and desolation indescribable. One of the most striking features of the scenery on the edge of the valley, is the concentric structure of the granite in the so-called “Domes,” and “Royal Arches,” of which more hereafter. Suffice it to say here, that the rounded, dome-shaped masses contrast remarkably with the sharp peaks above and beyond them; they rise front three to five thousand feet above the valley, presenting toward it a sheer precipice of nearly this height—domes of the most graceful curves, and on a stupendous scale. This concentric structure, according to Whitney, is not the result of the original stratification of the rock, and there are no evidences of anticlinal or synclinal axes or marks of irregular folding; the curves, arranged strictly with reference to the surface of the masses of rock, show, according to him, that they were produced by the contraction of the material while cooling or solidifying, giving one the impression that he sees the original shape of the surface. The concentric granite plates overlap each other, absolutely preventing ascent from the valley; as these immense plates have fallen, some from a height of over 3,000 feet, detached by the frost, and other agencies, they have left the enormous cavities which have received the name of the “Royal Arches,” and royal indeed they are.

All observers agree that the snow disappears from the highest summits rather by evaporation than by melting, and that the air there is remarkably dry; and by this is explained the general absence of glaciers on Mt. Shasta and similar elevations, where in the Alps glaciers would exist; immense masses of snow, miles long and hundreds of feet thick, remain all summer, thawing and freezing on the surface, gradually wasting away without becoming glacier ice, and yielding comparatively small streams of water. Still, at a comparatively recent geological period, immense glaciers existed in these mountains, and the usual traces of scratched and polished surfaces are common enough, and moraines of great extent are found—these evidences of former glacial action, however, seem to be limited to the higher parts of the range, and not to descend below 6,000 feet above the sea, except in a few exceptional cases, where the configuration of the upper valleys was favorable to the accumulation of large masses of snow—this indicates at that period a considerably moister climate than now exists there. Glaciers extended from Mt. Dana (13,000 feet above the sea) to a level of the upper border of the great Yosemite, or 7,000 feet above the sea, the bottom of the valley being 3,000 feet lower. The weight of an ice sheet a mile in thickness, may have had something to do with the sudden subsidence which many geologists think was in part the cause of the formation of this valley. Marks of glacial action are manifest on the “Sentinel Dome,” and on “Glacier Point,” both groovings and polishings; this polishing extends far down the smooth surface on the south side of the valley, near the Illilouette Cañon, a steep, gigantic slide for a thousand feet, of perfectly smooth rock, which makes one dizzy to look at from above or below, ending, as it does, in a vertical wall toward the valley. There are no signs, that I know of, of glacial action in the valley. The Little Yosemite Valley, 2,000 feet higher than the big Yosemite, but greatly resembling it, communicates with the latter by the Nevada Fall, the main stream of the Merced River running through both. No doubt a glacier passed down the Illilouette Cañon from the Mt. Starr King group to the edge of the valley; the land at the head of the Merced River was not high enough for the formation of a glacier into the Yosemite Valley, and there is no evidence that it came beyond the edge, as above stated, though it doubtless filled the higher Little Yosemite.

The famous valley is about 155 miles from San Francisco, a little south of east, or 250 by the usual line of travel. It is best to stop, when coming from the east, at Stockton, distant ninety miles from San Francisco by rail. I went by the Mariposa route, the longest, with the most horseback-riding, but leading near the Mariposa grove of big trees, and affording, on the whole, the grandest views. We took a private conveyance, three of us and a driver, at Stockton, the usual charge for which is $16.00 a day, including the food and all expenses of driver and two horses; the stages are crowded and uncomfortable, (though, from experience, I think not more so than the private carriage,) but are considerably cheaper and quicker, as they travel day and night. By this route you have about twenty-five miles to go on horseback, mostly up and down steep and rough trails, to reach the valley—this we did in one day; but it is better to take two, as both horses and riders get greatly fatigued.

You cannot enter the valley without rising about 3,500 feet above the point you wish to reach, viz.: the bottom of the valley—this is 4,000 feet above the sea, and so is the ranch of Mr. Clark, from which you start; from this you ascend to 7,400 feet, and then descend about 3,500 into the valley. This severe, but necessary, toil, is what, with the dust and heat, makes the journey so fatiguing. You can do it all on horseback, as Mark Twain’s pilgrims did in the Holy Land; but pity for the horse, and comfort, it not safety for the rider, impels you often to dismount, exchanging the fatigue of climbing for the weariness and soreness of the saddle (it is, for the first few days, a sort of drawn battle between the abductor muscles of the thighs in riding, and the muscles of the calves in ascending or descending on foot). The cañon of the Merced River, whose shallow and placid stream runs through the valley, has such steep sides, that a trail there is next to impossible for any one but an Indian or an Alpine climber; and so the valley has to be entered from the side, at the western extremity, either by the Mariposa trail on the south, or the Coulterville trail on the north.

| Online Library: | Title | Author | California | Geology | History | Indians | Muir | Mountaineering | Nature | Management |

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/wonders_of_the_yosemite_valley/04.html